Illustrators of fairy tales frequently choose styles that evoke the periods of history not particularly related to the tales but that they perceive to share the values they find in the tales.

Perry Nodelman, Words About Pictures

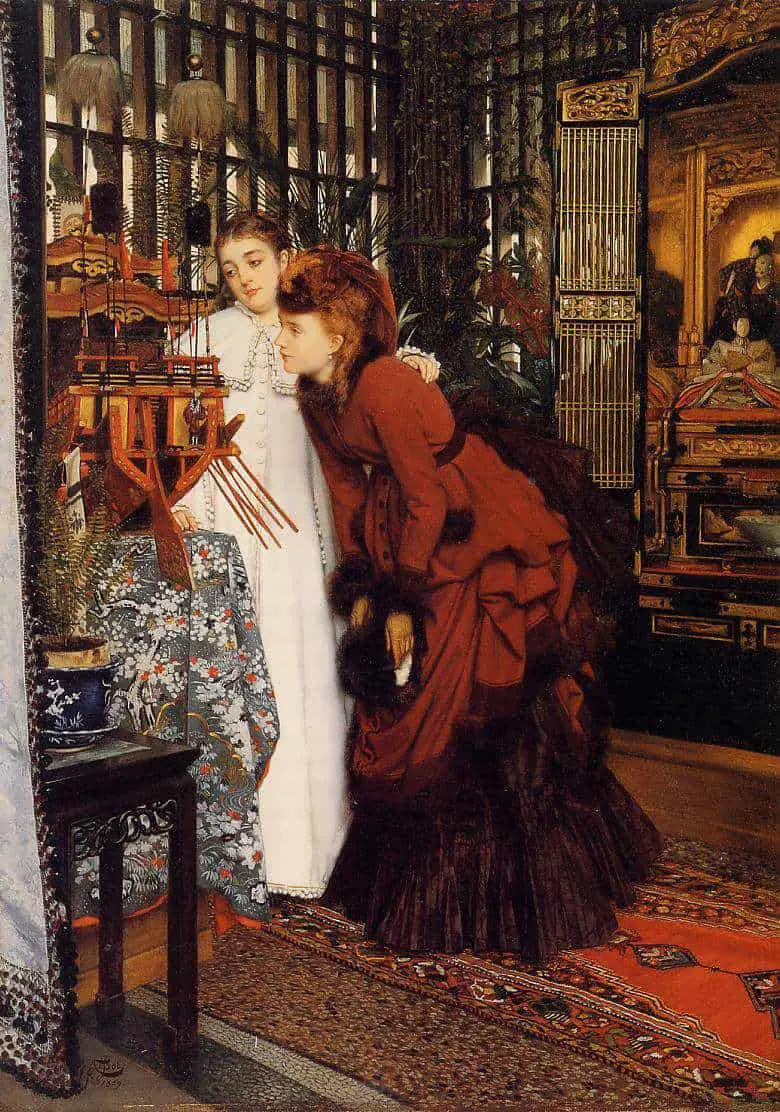

Children’s picture books draw from a great number of traditions. One of those is ‘chinoiseries’, a European mimicry of Chinese art.

Chinoiserie: a decorative style in Western art, furniture, and architecture, especially in the 18th century, characterized by the use of Chinese motifs and techniques.

The word ‘chinoiseries’ denotes a European art style dominated by pseudo-Chinese ornamental motifs evoking a romanticized or fairy-tale East. [… This] style exudes a longing for a newly romanticized medieval “Cathay”.

Objectifying China*, Imagining America: Chinese Commodities in Early America by Caroline Frank

(In earlier eras, Northern China used to be known in English speaking areas as ‘Cathay’, from ‘Catai’. The south was called ‘Mangi’.)

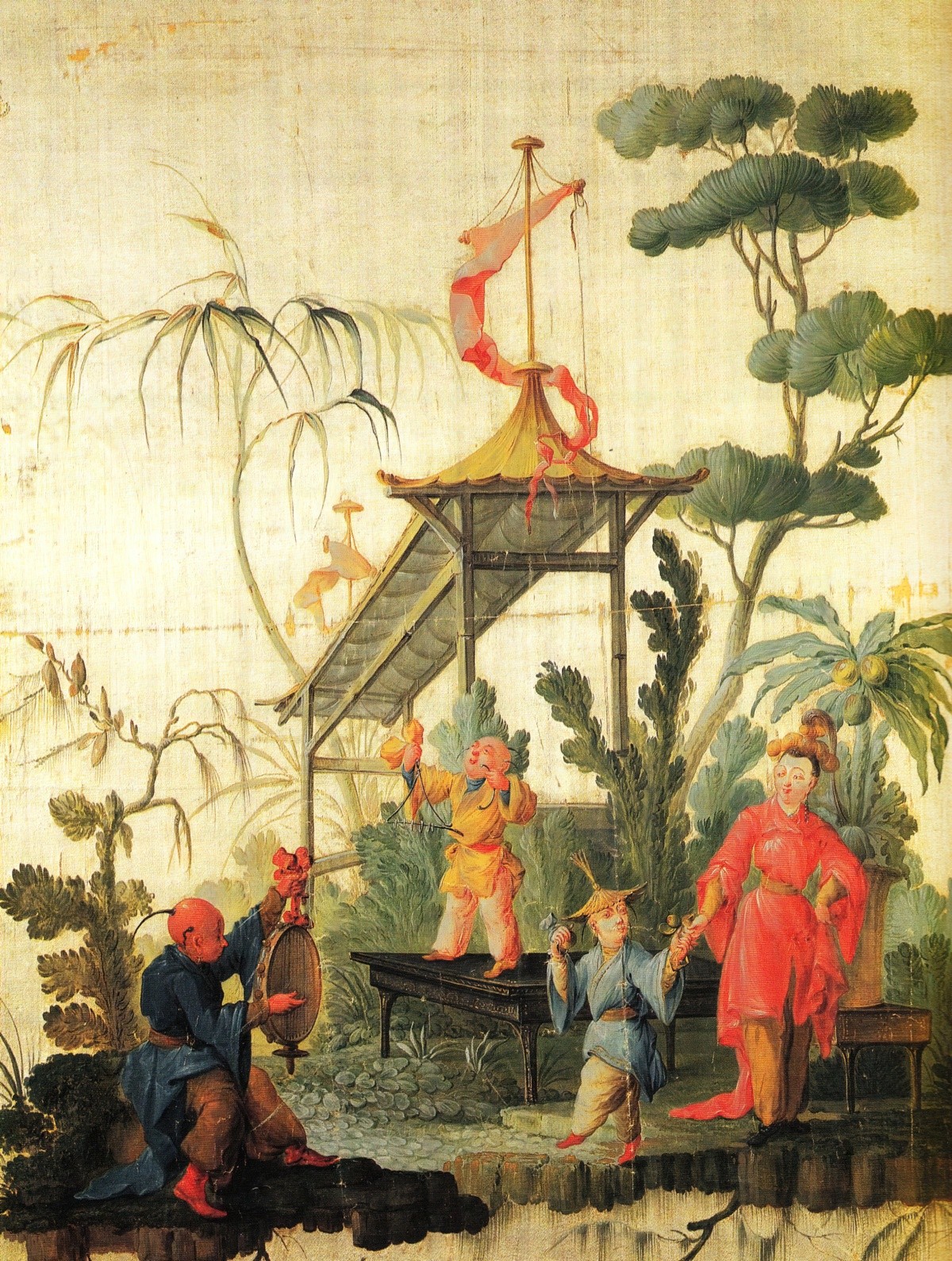

A standout example of chinoiseries are the popular engravings of French artist Francois Boucher (1740s onwards).

Francois Boucher’s Chinese paintings

Boucher borrowed details from:

- Chinese woodblock prints

- a Turkish designer

- Arnold Montaneus’s 1671 Atlas Chinensis. Montaneus was a Dutch teacher and author.

Japan Work (late 17th century — 19th century)

This term referred to pseudo-lacquered furniture featuring chinoiserie decorations actually applied in Europe. It also referred to tin-glazed earthenware pottery, metalwork and textiles with the same decorations.

Furniture which has undergone this treatment is said to be ‘japanned’.

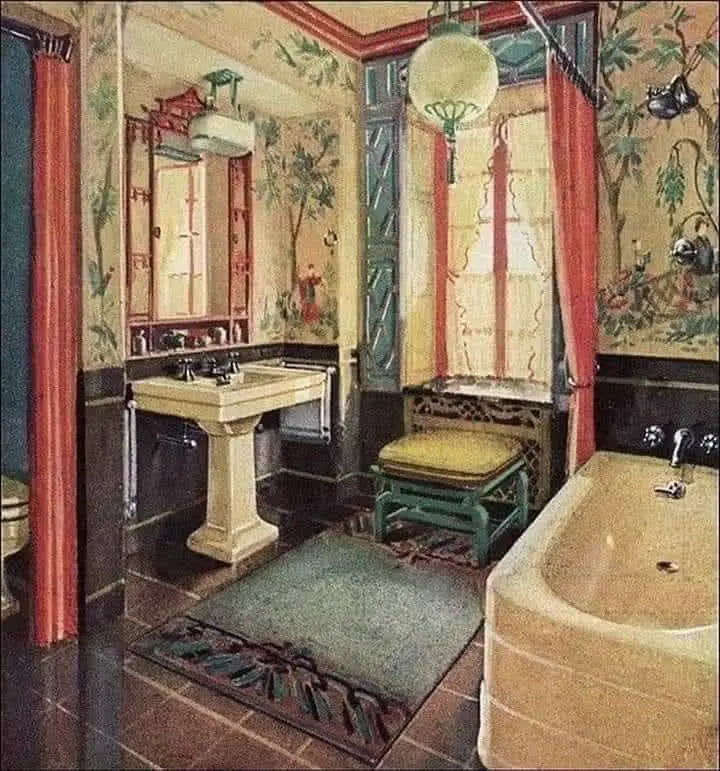

Modern Chinoiserie

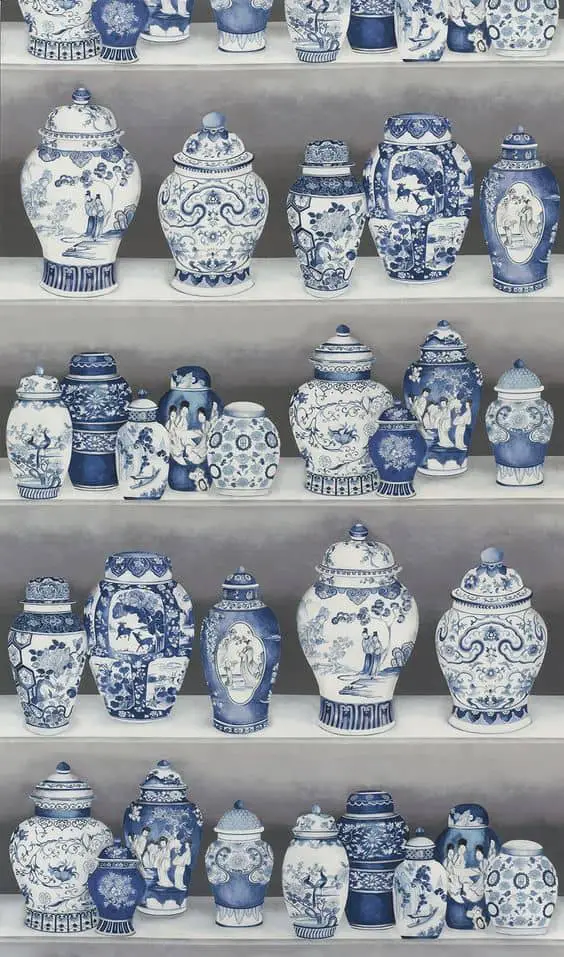

Perhaps you have some examples of chinoiserie in your own environment?

Features of Chinoiseries

- Tropical exoticism is exaggerated

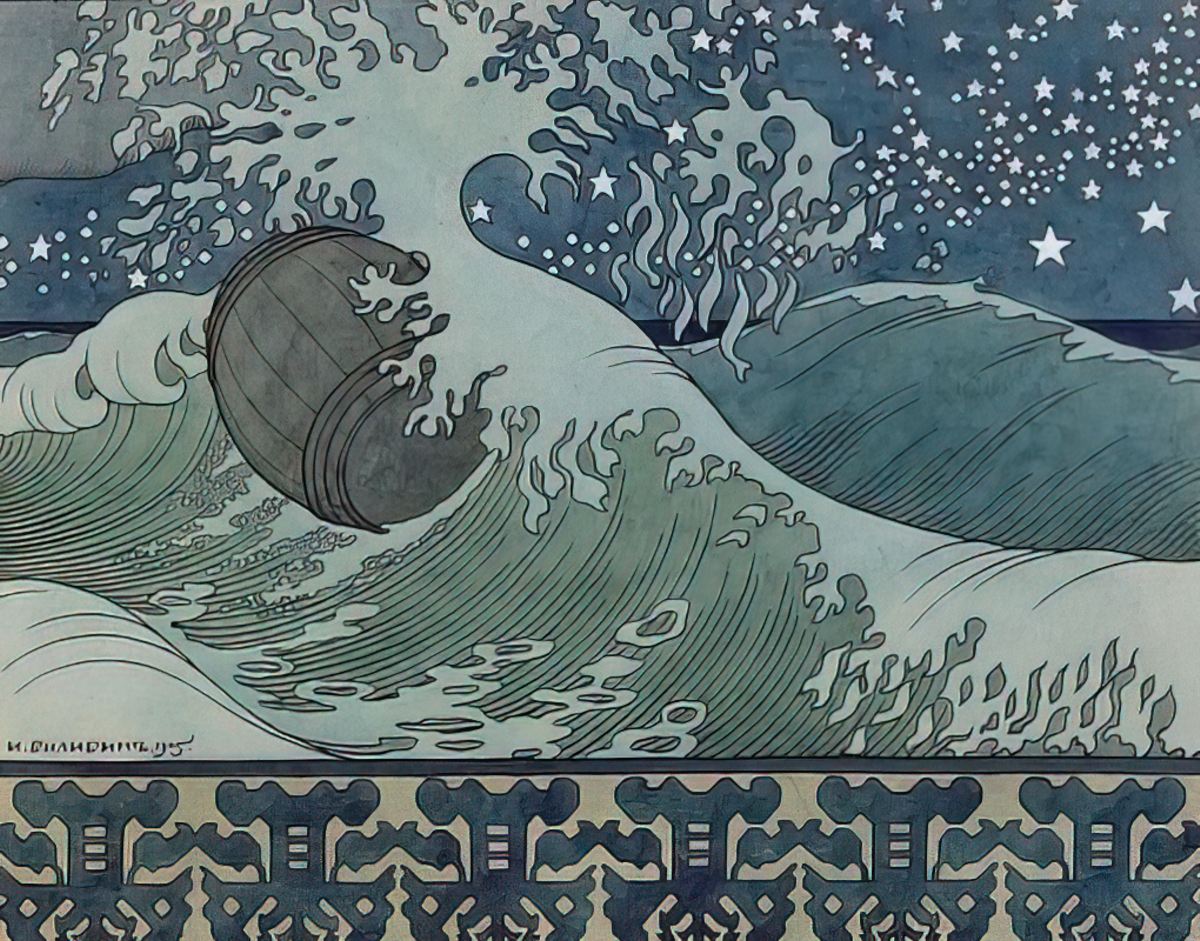

- It is based on a fanciful European interpretation of ‘Chinese’ styles which may not be Chinese at all, but from Japan, Korea or Turkey. In earlier eras (and into the present) Westerners were unable to distinguish between different parts of the East. It was simply ‘exotic’. If it’s Western art inspired by Japan, then some use the word ‘japonaiserie’.

- Chinoiserie was most popular during the rococo period (1750-70), a movement known for its light-heartedness but also for its heavy detail.

- It’s not really Chinese or even Asian art, because the materials required to create it weren’t available in Europe or America.

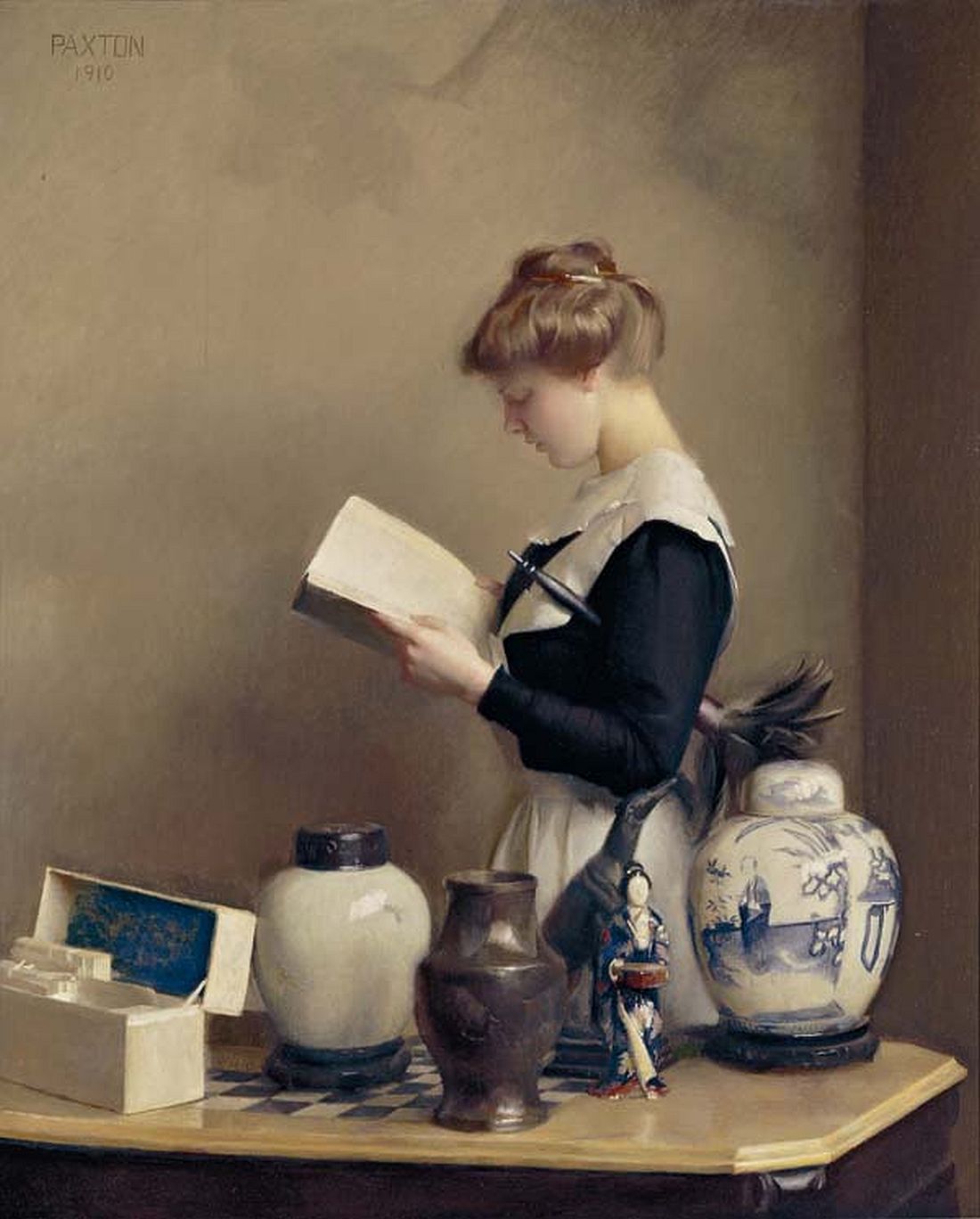

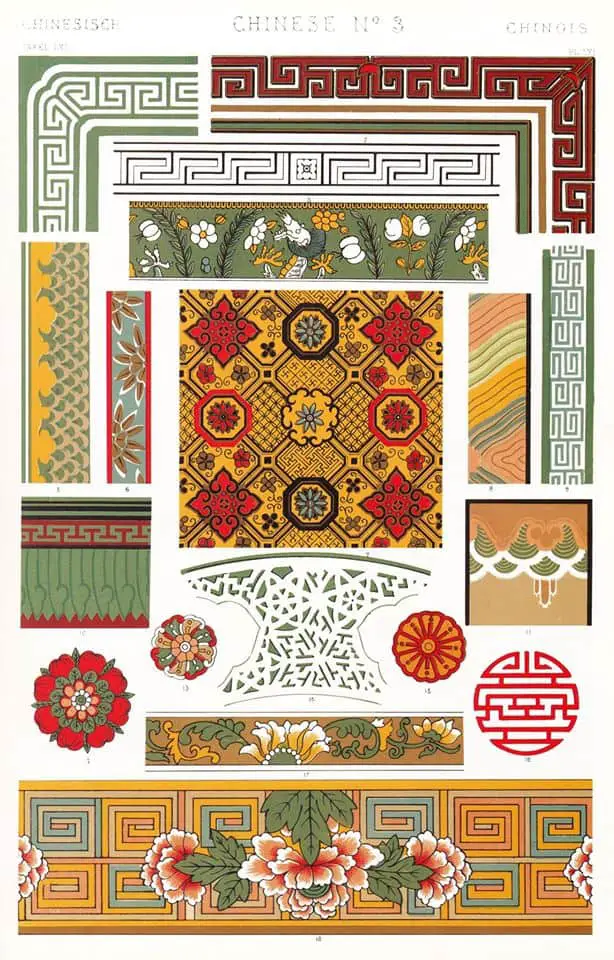

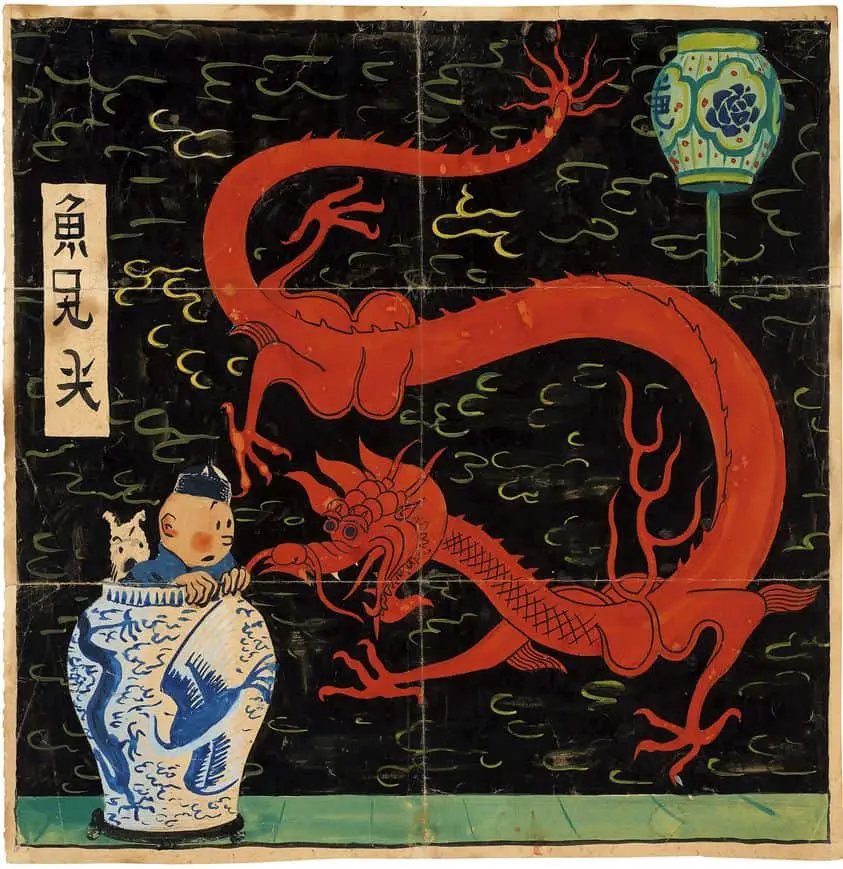

- Dragons, exotic birds, ‘Chinamen’ and women dressed in traditional Chinese clothing, fu-manchu beards, ponytails, multi-tier structures with those pointed, sweeping up roofs (pagodas), pink and white lotus leaves, bamboo plants, weeping willows and other Chinese vegetation, blue-and-white ware, hump-backed bridges, water gardens, misty mountain-scapes

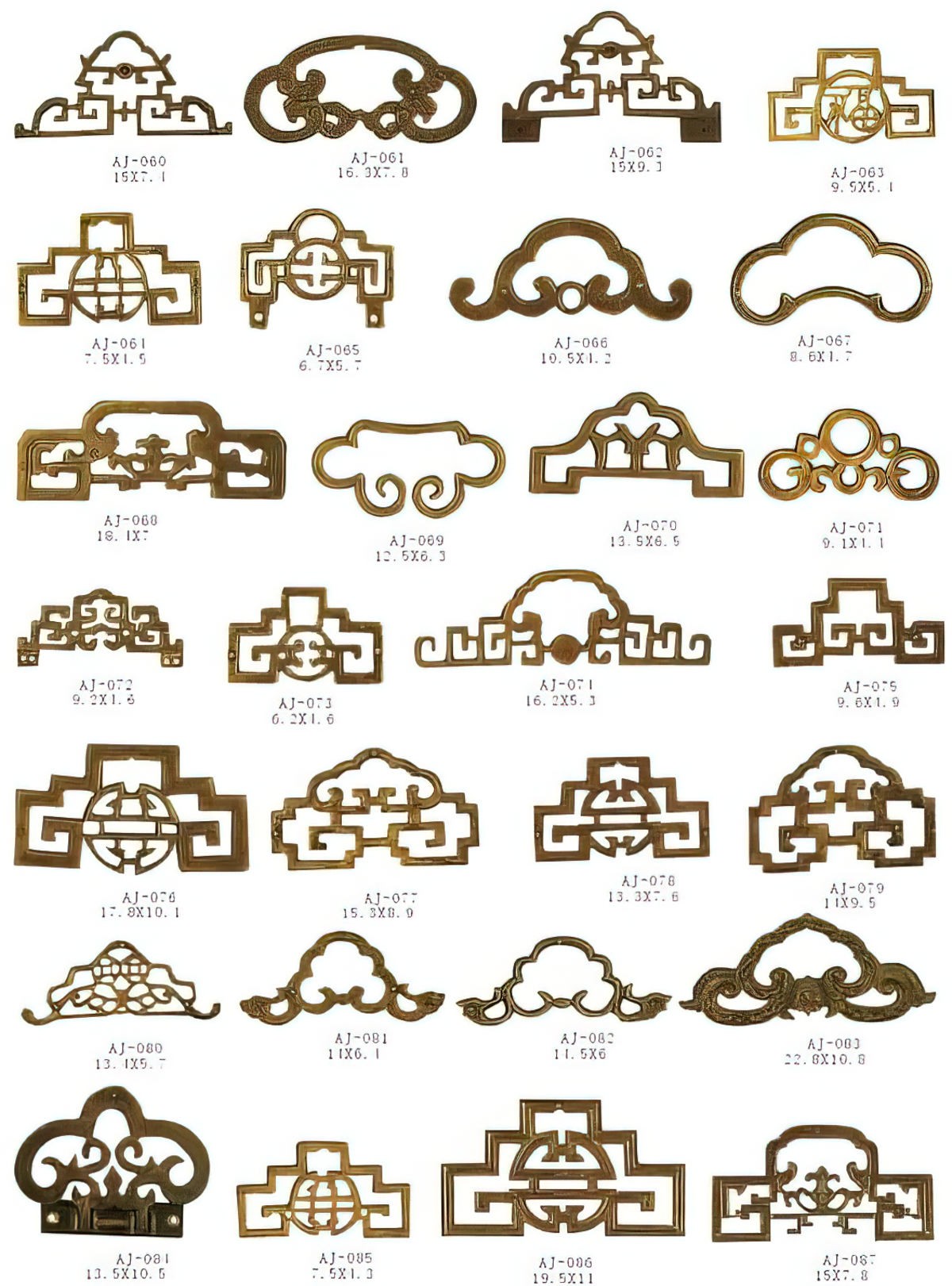

- Chinoiserie may contain shapes such as this:

CHINOISERIE AND CHILDREN’S LITERATURE

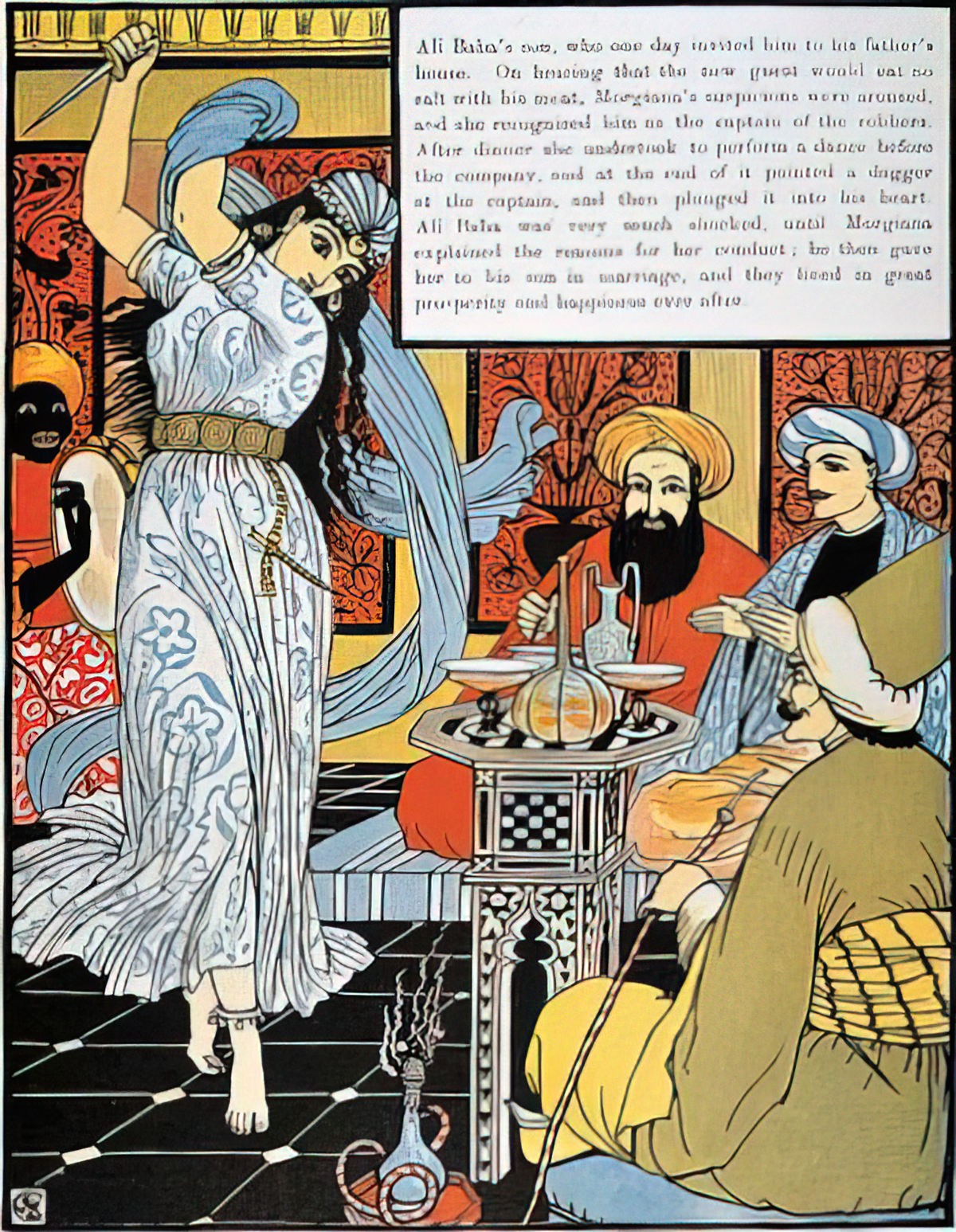

The standout example of fake Eastern stories influencing the views of Western children are Tales of the Arabian Nights.

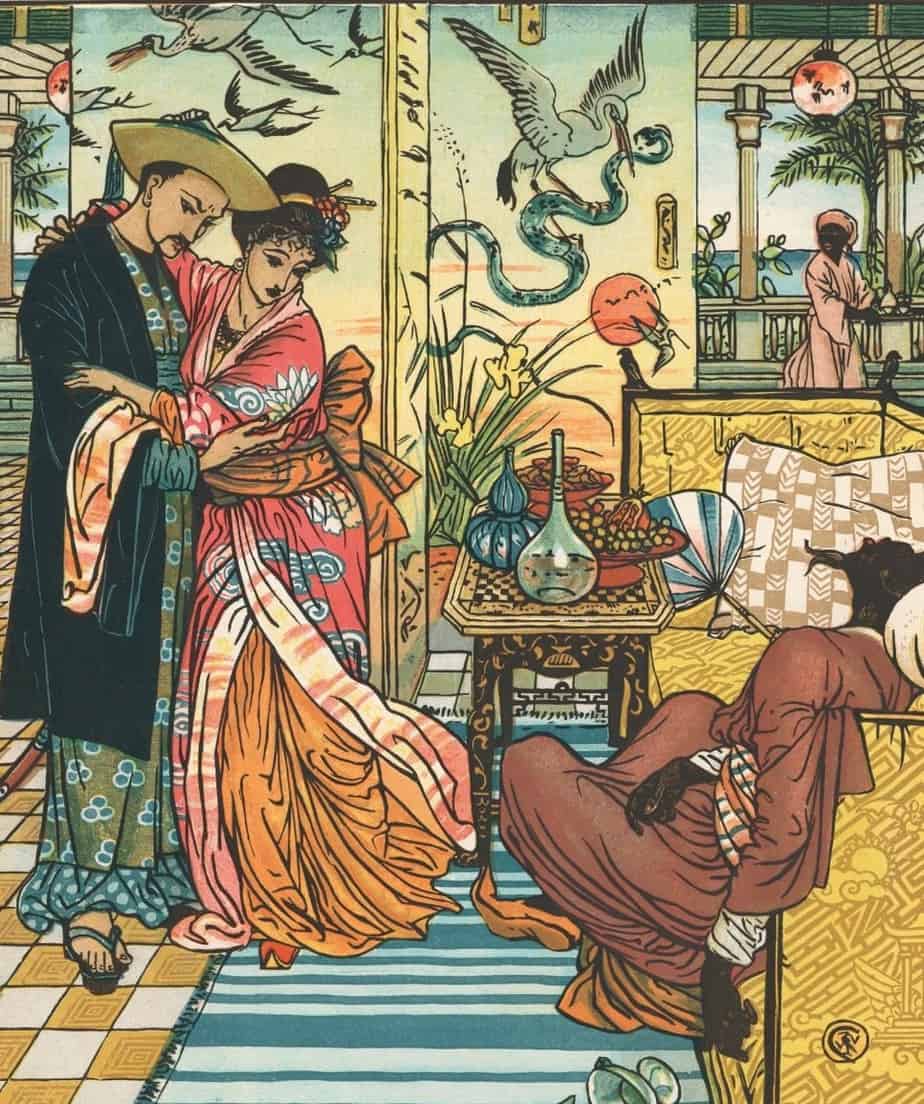

I was given an anthology of Arabian Nights as a kid and this thick book sat on the shelf right beside the Grimm fairytales. My edition was more modern, but it was Walter Crane who came out with the first picture book on Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves and Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp. These were coloured lithographs. The story was ostensibly about a Chinese boy and set in China, though Crane was actually influenced by Japanese woodcuts, especially those by Hiroshige.

Other examples can be found among the illustrations of Hans Christian Andersen’s pseudo-Chinese “The Nightingale”. The art in an edition illustrated by Nancy Ekholm Burkert is a mixture of chinoiserie and art nouveau.

Header painting by Austrian Carl Moll, artist of the Art Nouveau era (1861 – 1945).