“The Brain In The Jar” is a short story by Norman Elwood Hammerstrom (c. 1900-1970) and R.F. Searight (c. 1902-1975).

Searight was a friend of Lovecraft. They swapped letters. Hammerstrom was a chemist. From this I understand that Hammerstrom brought scientific knowledge and Searight brought sci-fi genre storytelling techniques to the table in their collaboration.

This standout brain in a jar story appeared in the June 1936 edition of Weird Tales Magazine alongside stories with titles such as “The Telephone in the Library”, “Loot of the Vampire” and “The Grinning Ghoul”.

Read it online at The Internet Archive. If you’d prefer to listen, you can find it Librivox recordings.

WHAT HAPPENS IN “THE BRAIN IN THE JAR”

SETTING

Berlin, Germany. March, 1919. Three in the morning. The war ended about five months ago on 11 November 1918, after four years of horror and fighting.

Picture a hospital on a rainy, foggy but also windy night. I just looked up whether it’s possible for a night to be both foggy and windy at once, since wind tends to clear fog. Yes, it is possible, in the case of advection fog also known as advected fog. The term advection means a horizontal movement of air. Unlike radiation fog, advection fog can occur even when it is windy. (You can also get valley fog and freezing fog. Those are the four types.) Sea fog is a type of advection fog, which forms in shallow horizontal layers when warm, moist air is cooled from below, usually by moving over cold water. (The different fogs look the same.)

However, once wind gets to 27.78 kph (15 knots), this clears ground-level advection fog. Long story short, the image of a ‘cold and foggy’ night with ‘fitful gusts of rain … dashed against the windows by the high wind which had come up at sunset’ is a non-mimetic atmospheric condition.

A fitting night for murder and crime of all sorts, thought the impressionable Eldridge, as he sleepily made his way back to his room.

“The Brain In The Jar”

VERNE ELDRIDGE

The main character is called Verne Eldridge. He is not exactly passionate about his job, working as an orderly at a Berlin hospital. This job provides a place to hide, with its dimly lit corridors. He’s been here for two months. He came in with fake stolen documents which he got from a wounded German soldier.

So long as Verne is stuck in Germany, he is on the run from agents. The war is technically over, but this guy is one of the best American intelligence agents in the biz. He’s still a wanted man.

Considering this guy is a wanted man and one of America’s best agents, who played a key role in winning the war against Germany, this sleepy dude ambling down a dim corridor mulling over the murderous weather seems somewhat unrealistic. The authors have created a low mimetic hero (to use Northrop Frye’s terminology).

DOCTOR JAEGER

The doctor in charge. From the odd remark, Verne thinks this guy is starting to realise his orderly is a secret American agent.

Although this is a hospital, Doctor Jaeger is a research doctor. They must be using this hospital as a research facility as well as a medical hospital. He’s a slim guy with a black beard who likes leaning on doorframes smoking cigarettes. His features are ‘strong’ and ‘sharp’.

The reason he has time to stand around smoking: his position at the hospital is a sinecure. I had to look that word up. It means he has no proper work to do. But it gives the holder status and an income, perhaps offered to keep them from doing other nefarious work which might benefit opponents.

Rumour has it that this Jaeger guy has been using his vast swathes of free time by conducting experiences of living tissue in special liquids. Successful experiments.

Turns out nobody really has any secrets around here, huh? Everyone’s all up in everyone else’s business, despite the dead-of-night cloak of invisibility.

Oh yes, Dr Jaeger also had a hand in concocting poisonous gases used by Germans during the war.

Basically, Dr Jaeger and Verne Eldridge are political enemies. And supposedly Dr Jaeger could murder Verne Eldridge very easily. Just pipe some gases under his door or something. We’re not given specifics, but Verne knows him to be a psychopath. (He doesn’t use the word psychopath, which was used differently when this story was written.)

From his own observation he knew Jaeger to be a cold, hard man, utterly without scruples and having a deep vein of cruelty in his nature which manifested itself from time to time in various characteristic acts.

“The Brain In The Jar”

VERNE DISCOVERS A SECRET DOOR

The American notices the evil German disappear through a door which Verne, spy extraordinaire, had assumed to be a fire exit. (Hell, this guy couldn’t bring the Germans down. He can’t even escape a hospital during a fire.)

The evil German also slams the door behind him. Wouldn’t a spy think, “Maybe he’s done that deliberately, hoping to lure me into an even less populated part of the hospital?” Especially when you realise this guy knows your special agent background?

Hell, I would not be following Dr Jaeger through that door. But Verne steps to the door and turns the knob, despite his professional training. He’s just a curious, curious little dude.

VERNE DISCOVERS DR JAEGER’S SECRET LABORATORY

And like any self-respecting evil genius, Dr Jaeger keeps shelf upon shelf of mysterious tissue in jars, as well as live guinea pigs. Poor little guinea pigs.

Verne realises that if this laboratory is so hard to find, the scientist must be concealing something dangerous here. He’s on high alert. (I’m not so sure this place is any harder to find than any other department in a hospital. Have you been to a large public hospital lately?)

the scientist would hardly have taken such elaborate precautions in regard to the privacy of his laboratory had he not had something to conceal

“The Brain In The Jar”

By the way, this logic is terrible, generally.

Or, maybe, there are safety reasons not to admit any old Joe Blow “orderly” into the science laboratory. Contamination, people messing around with stuff, stealing chemicals for recreational use… I can think of many reasons why Dr Jaeger doesn’t leave his lab unlocked, and also, a hospital isn’t designed to be deliberately labyrinthine and confusing. Labyrinthine and confusing is just how hospitals turn out, because they have lots of parts to them, with separate doors for staff and the public etc.

ELDRIDGE SPIES THE BRAIN IN THE JAR

He’s overcome by the willies and is about to hotfoot out of there when he notices The Jar.

The jar itself is somewhat personified. It’s got a ‘mouth’. It has a German cross for a knob. (I can’t actually visualise this. The main thing is, this jar is hooked up to a network of tubes and wires disappearing into the wall. Also a thermometer.

Sounds high tech.

However, the contents of the jar are more interesting. Two eyes, suspended in reddish-black but also transparent liquid. Also a human brain, perfectly preserved. The brain sits on a cushion on a glass pedestal.

The hideous spectacle resembled a huge snail.

Ooh, I wonder what Stable Diffusion will do with that…

ELDRIDGE ESCAPES THE LAB

After losing track of time, he hears people coming but manages to escape unseen and unheard.

RETURN TO THE LAB

Eventually the evil scientist takes a trip and the hapless American spy is once again able to go inspect the creepy laboratory. He is making a sketch of it, presumably to hand to the American government.

But it turns out the brain is sentient. It’s trying to tell him something. Not only is the brain sentient, it has powers of telekinesis and hypnosis. It puts Eldridge into a trance, makes him write on his own pad, “Be here at midnight tomorrow” and also freaks him out by suspending a test tube in mid air and then dropping it. Way to get someone back. I’d be gone forever.

THIRD TRIP TO THE LAB

The brain makes Eldridge write down a gruesome tale in French. He’s a polyglot this American, with German skills at native level (otherwise he’d be outed as American) and a reading command of French.

THE STORY WITHIN A STORY

The brain belongs to a French man called Jean Perrin who is taking quite a lot of credit for the downfall of the German forces. As a result, he was captured and imprisoned in the surprisingly fairy tale setting of a turret in the old castle of a Prince, just outside Berlin. After Armistice they decided not to release him. Instead, he was brought to this hospital and strapped down.

When he woke up from his anaesthetised state he was shocked to realise he was now only a brain with eyes on stalks. Well, ‘nerve cords’. (The villains had been kind enough to provide him with a mirror on the opposite wall.)

This trauma no doubt resonates with many people during the wars, in which most people would’ve known a man (or been that man) who woke up on the operating table to realise they were now minus a limb or four.

All he’s got is his sense of sight.

The brain has been careful not to let on to his evil scientist opponent that he’s conscious, and has been praying for death. Meanwhile, the scientist has been carrying out all sorts of experiments, applying chemicals and whatnot.

But as it happens, he’s hooked up to some ‘secret fluid’ and using this liquid, Jean Perrin developed willpower. And also telekinesis. Without the constraints of the body, the brain realised anything at all was possible, and that he could eventually rule the world.

However, that’s not what this brain wants. Nope, he just wants revenge. He asks the American to help, since the American still has legs and whatnot.

Personally, I think the brain should do his own dirty work. Telekinesis and hypnosis are better than legs and whatnot.

ELDRIDGE DOES AS HE’S TOLD

Eldridge the high-level spy conceals himself behind the guinea-pig cage the following night. Not a bad spot when you think about it, because guinea pigs make some level of noise. If your stomach happened to rumble or a small fart popped out, the evil genius might simply think it was the guinea pig.

DR JAEGER STARTS SLICING AND DICING

From his concealed spot, Eldridge is able to see that Dr Jaeger arrives, and takes tissue from a living human arm. For half an hour he sets about slicing it up. For a sashimi platter? Nope, to observe under a microscope.

Eldridge did not grow impatient. The uncanny affair held him enthralled.

“The Brain In A Jar”

SANDBAGGING PAYS OFF

Sandbagging is the official Poker term for bluffing that your cards are bad. The brain is doing something similar here, pretending to be a slab of brain tissue in a jar, all the while accumulating skills to take over the world.

Now the brain kicks into action. Like an evil poltergeist, he upsets all the chemicals in the lab and brings them upon Jaegar until the guy is motionless. Then the shelf holding the jar breaks, and brain falls into the fire. The brain acts as accelerant.

Eldridge gets hit by a flying bottle and is knocked out. Turns out the brain wanted to kill him too, I guess.

ELDRDIGE WAKES UP

You might think that a hospital is a good place to have a calamity. Doctors and nurses are right there to help you.

But no, when Eldridge comes to he’s actually on a hospital ship bound for New York. The Germans don’t want an American spy in their midst so they’ve packed him off home.

He’s with his wife and also a deus ex machina friend called Felton who we didn’t know about until now. This friend, also in the SS, saved Eldridge from the burning hospital. Which explains things further.

CARED FOR BY THE HELPMATE

To them [Eldridge] related his weird tale, and with shattered nerves and seared body resigned himself to his wife’s loving care. Her love alone can efface from his mind the effects of the memory of the vengeance of the brain in the jar.

“The Brain In The Jar”

A BRIEF HISTORY OF BRAIN METAPHORS OVER TIME

This interwar (interbellum) period story conceived the brain as a fantastical object, but also as:

- a separate entity from the rest of the body, like slotting a memory card out of a device

- a piece of electrical equipment with tubes and wires

- an organ with unlimited potential, if only it weren’t confined to the human body, with its meaty limitations. This is similar to what we now know about neural pathways, and how we learn. The more we use a neural pathway, the stronger those pathways get.

In “The Brain In The Jar”, the revolving opaque-to-transparent liquid inside is a fantasy object, but does suggest some kind of valve at play, with an on-off switch.

These days, we commonly use computers as a metaphor for the human brain.

BRAIN AS COMPUTER

The way we think about the brain has changed over history. And the reason for that change is not simply because we knew a lot more than we knew in the past. That’s kind of fairly obvious. But rather, the way that we interpret facts changes in particular with technology and with the metaphors that we use to describe the brain, which are generally drawn from technology. So the most obvious thing is, you think, if you explain to someone what’s the brain like, well it’s a bit like a computer it’s processing information, that kind of thing. We’re using a technological metaphor, the computer, to explain what the brain does.

Matthew Cobb, author of “The Idea of the Brain” at the Brain Science podcast with Ginger Campbell, MD (April 2020)

But what metaphors were used before the age of computers?

BRAIN AS TELEPHONE EXCHANGE

Previous to the invention of the computer, people suggested the brain was like a telephone exchange. In fact I’ve seen this quite recently, this metaphor, in an article in Nature Neuroscience, about two years ago. Somebody described the brain as being like a telephone exchange.

Matthew Cobb, author of “The Idea of the Brain” at the Brain Science podcast with Ginger Campbell, MD (April 2020)

BRAIN AS TELEGRAPH SYSTEM

Earlier than that, in the nineteenth century, brains were seen as being like the telegraph system. You can imagine there’s a telegraph system spread across Europe and across America and there’s this stuff going down the telegraph wires. People thought well, that looks a bit like the nervous system. Maybe that’s what’s going on in the brain…we can understand it in that way.

Matthew Cobb, author of “The Idea of the Brain” at the Brain Science podcast with Ginger Campbell, MD (April 2020)

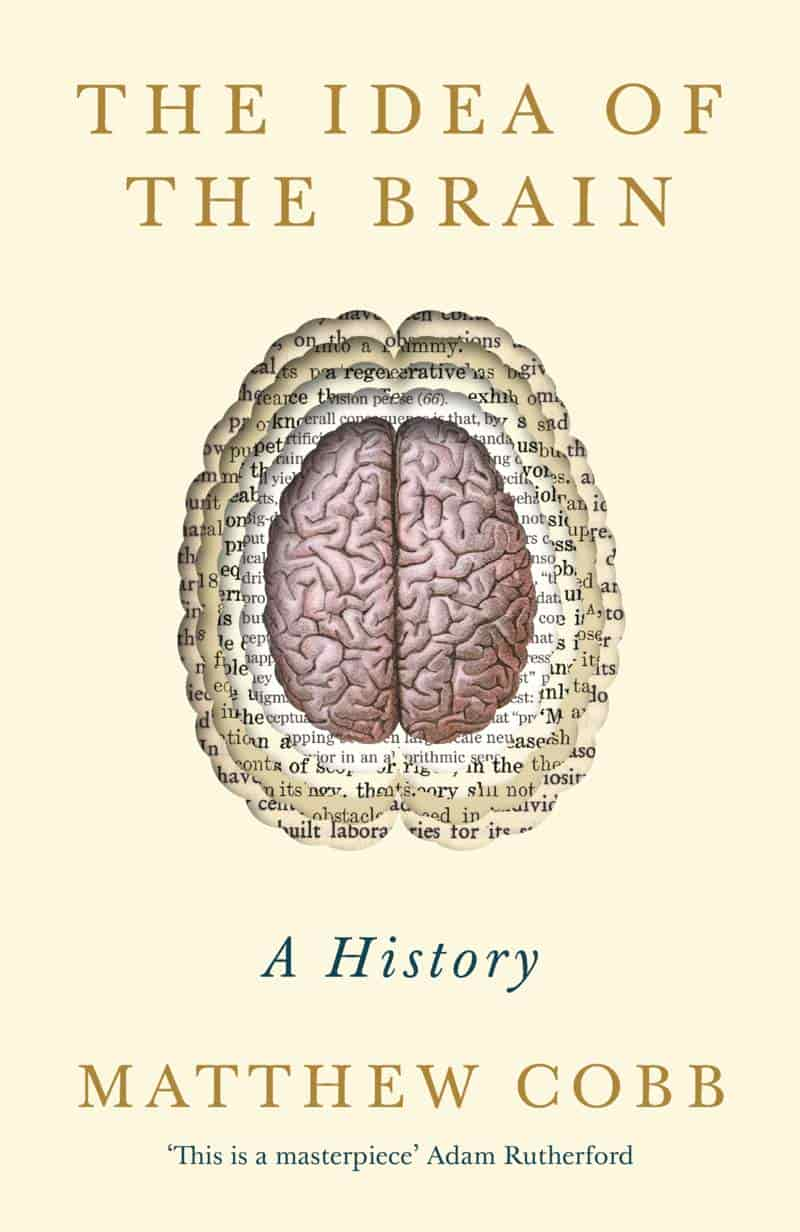

THE IDEA OF THE BRAIN: A HISTORY BY MATTHEW COBB (2020)

This is the story of our quest to understand the most mysterious object in the universe: the human brain. Today we tend to picture it as a computer. Earlier scientists thought about it in their own technological terms: as a telephone switchboard, or a clock, or all manner of fantastic mechanical or hydraulic devices. Could the right metaphor unlock the its deepest secrets once and for all? Galloping through centuries of wild speculation and ingenious, sometimes macabre anatomical investigations, scientist and historian Matthew Cobb reveals how we came to our present state of knowledge. Our latest theories allow us to create artificial memories in the brain of a mouse, and to build AI programmes capable of extraordinary cognitive feats. A complete understanding seems within our grasp. But to make that final breakthrough, we may need a radical new approach. At every step of our quest, Cobb shows that it was new ideas that brought illumination. Where, he asks, might the next one come from? What will it be?

Matthew Cobb wrote his history of the brain to investigate how metaphors have helped our understanding of the brain, but also how metaphors have hindered our understanding of the brain.

That’s the thing about metaphors. They’re incredibly powerful, but they’re like a framework. A framework helps you, but it also traps you. It’s very difficult to imagine outside of that. The implication of this — and this is where scientists get very excited, when you explain this to them — that the metaphor is limiting you, is that in the future, we’ll understand the brain in a different way. As new technology arrives new metaphors are discovered.

Then they want to know, “Well, what’s it gonna be? What will this new understanding consist of?”

Unfortunately I don’t have an answer, otherwise I’d be extremely wealthy!

Matthew Cobb, author of “The Idea of the Brain” at the Brain Science podcast with Ginger Campbell, MD (April 2020)

Cobb then explains that this is how science works: A series of misunderstandings and failings which change over time. Sometimes when we don’t grasp something, it’s because a fact is wrong. But more generally, we’ve got the ideas (theory) wrong, not the facts. Of course, in retrospect, every scientific breakthrough looks absolutely obvious.

FURTHER NOTES FROM THE INTERVIEW

Important discoveries made before 1950:

- In the 19th century the idea emerged that neural networks don’t just make things happen. They also stop things from happening e.g. unnecessary reflex actions.

- In the 1920s and 1930s the idea emerged that brains had something to do with information.

- These two key ideas lay the foundation for our current understanding of the brain.

- Our ideas about the brain haven’t changed all that much since about 1950.

Post 1950, brain science is influenced by advantages of technology in areas such as:

- tech

- genetics

Phrenology is a bunkum idea which began at the end of the 1800s and proliferated throughout most of the 1900s that one can look at bumps on the skull and deduce someone’s true character. One thing it (inadvertently) got somewhat right: introducing the idea that different parts of the brain did different things. Brain science wouldn’t be where it is now without the extended popular interest in pseudoscience.

(Physiognomy is the assessment of a person’s character or personality from his outer appearance, especially the face. You can find it easily in classic children’s literature.)

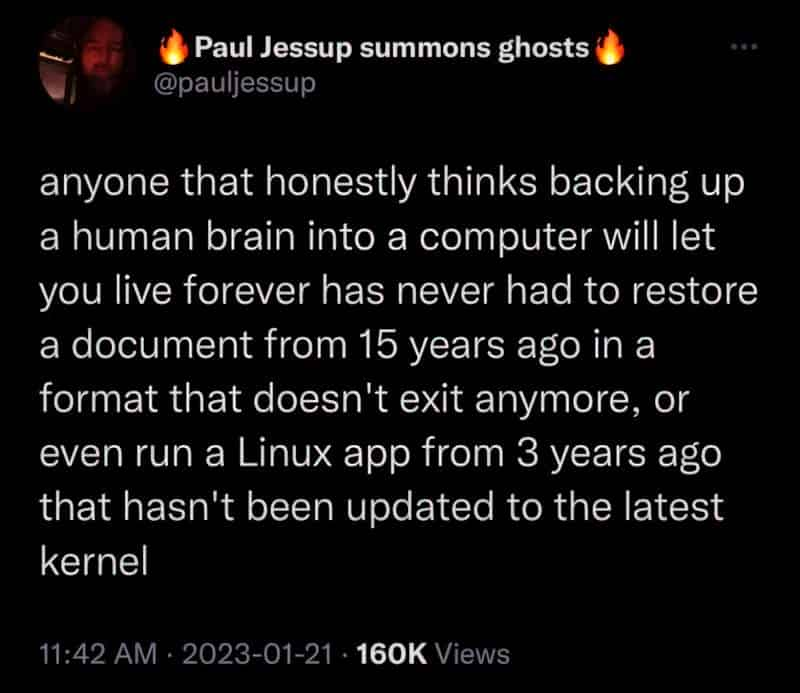

Matthew Cobb’s book was published a few years before the advent of ChatGPT, which seems to be changing brain metaphors once more. Now everybody’s talking about ChatGPT, artificial intelligence (AI) and the increasingly imaginable horizon of artificial general intelligence (AGI).

CHATGPT: THE INSTRUMENTAL (SILICON VALLEY) VIEW OF TECHNOLOGY

Yet still, it is tempting to revisit stories from the 1930s.

Happily, if I want to learn about mushrooms I don’t have to decapitate five hundred recent college graduates, although, to be fair, neither did the mad millionaire, whose experiment exists only in the pages of the May, 1931, issue of the science-fiction magazine Amazing Stories. Instead, all I’ve got to do is command OpenAI’s ChatGPT, “Write a thousand word synopsis of the knowledge of the world on toadstools.” Abracadabra.

from a 2023 article in The New Yorker

(The 1930s short story is “When the Moon Turned Green“ by Hal K. Wells.)

Describing what has been termed ‘The Instrumental View of Technology’, in which Silicon Valley characterises all tools and techniques as fundamentally neutral phenomena used by humans to achieve their ends, Richard King has this to say:

[The Instrumental View of Technology] considers the human brain itself a piece of technology which can be retooled for greater efficiency. For example, when defenders of new technologies say their use will free up space for students to dedicate to other tasks, they are reproducing the very conceptual model, call it the Brain-Computer Model, that led the adepts of AI to pursue the dream of natural language processing in the first place. They are also sorely mischaracterising the process by which human intelligence is created.

Richard King, ‘Machine Learning’, The Monthly (Australia), April 2023 (written article here, behind a paywall)

FURTHER RESOURCES

In this episode of Talk Nerdy, Cara is joined by neurologist Dr. R. Douglas Fields to talk about his new book, “Electric Brain: How the New Science of Brainwaves Reads Minds, Tells Us How We Learn, and Helps Us Change for the Better.” They discuss the discovery of brain waves in the 1920s and how this incredible science has more recently led to innovation in understanding human behavior, treating disease, and beyond.

Alongside the brain, cities are also frequently compared to computers in “computational models of urbanism”. This metaphor is critiqued in A City Is Not A Computer: Other Urban Intelligences by Shannon Mattern (2021).