The ‘Tall Tale’ is a legitimate genre of story – not necessarily an insult. Maybe it sounds like one because as kids we were told to stop telling ‘tall tales’, when in fact we just thought we were ’embellishing’ real-life happenings. (If you’ve always been a writer than I expect you might identify with that!)

- Mark Twain was a teller of tall tales.

- Paul Bunyan told jokes about rural yokels and political heroics.

- Gulliver’s Travels almost fits into the category.

- The potboiler Western is a type of tall tale, full of braggadocio.

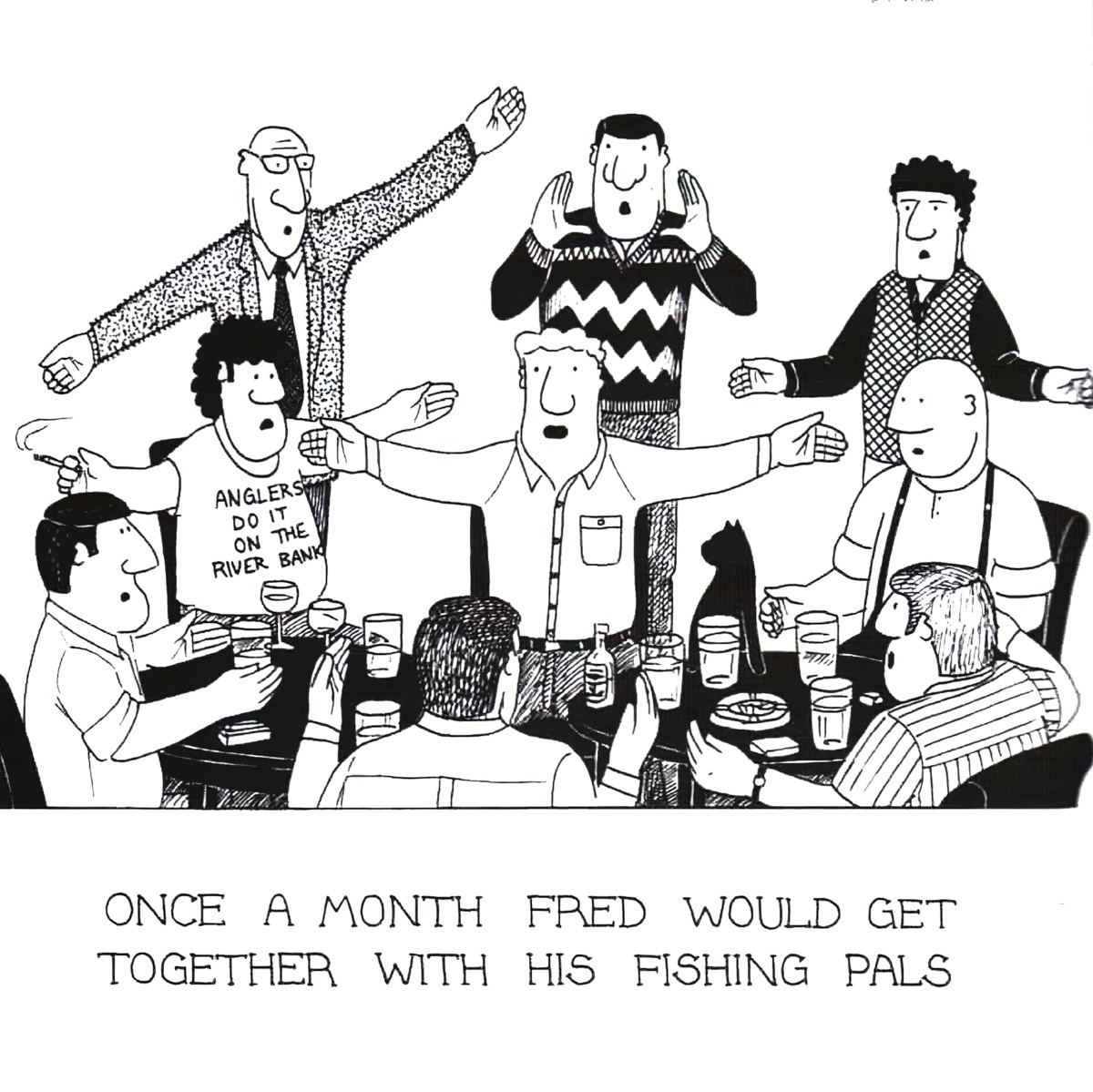

The tall tale seems to be a particularly masculine form. They are competitive — who can tell the best one? Tellers participate in ‘capping’ contests in which someone tells a tall tale, and others join in to make it even better — a kind of narrative exchange. The aim is to make the tales increasingly outlandish. Who can get away with the greatest exaggeration? The ‘getting away with’ is as important as the exaggeration itself. The Australian tall tale serves to reinforce ‘mateship’ (to reaffirm the solidarity of a group).

In a sense, tall tales are satirical. What do they satirise? Often themselves, or the art of serious storytelling. They make fun of people who would believe everything they hear. Tall tales are not meant to be believed.

But when it comes to tall tales, it’s not about the story content but all in the story’s telling. This is an oral tradition. The sound of the voice is key. The storyteller speaks in the local vernacular (of men, particularly white men). Names are familiar to the audience. Tall tales require not a reader but a hearer. In this way, a tall tale is a type of exchange. The speaker’s face is also important. He might wink or show mock surprise or make an expression to convey that what he is saying is not true.

The main requirement of a tall tale is exaggeration: There are unbelievable creatures, huge fish, large distances, huge volumes. But hyperbole alone does not mean ‘tallness’. In a tall tale, the listener must both accept and refute. The listener has to know enough of the environment in which the tale is told to realise this can’t be true. The line between fact and fiction is hazy, and the humour derives from pushing that boundary. Which parts of this story are true, and which aren’t?

Tall tales have their origins in folk tales. The tall tale is a Eurasian form of story, and has its roots in The Canterbury Tales and similar.

In Australia, the celebration of the liar is a recurrent motif. Someone who starts rumours is called a ‘Tom Collins’. Tom Collins was the pseudonym of Joseph Furphy. A ‘furphy’ is a lie or a made up story. See also illywhacker.

But it’s worth making a distinction between ‘fictive’ and ‘fictitious’. In a fictive tale the listener knows what he’s hearing is not true. Not so in a fictitious tale, in which he’s genuinely duped.

What’s the point of a tale which is obviously a lie? Lies should not be read as simply an intent to deceive but as a strategy designed to invite closer attention. In this way, a tall tale can subvert.

The following is from author Amy Timberlake, explaining her journey toward publication:

In 1999, after about eight publishers passed on “The Dirty Cowboy,” I sent the manuscript to Charlesbridge Publishing, and a few months later found a kind, personal rejection from Harold Underdown. His letter mentioned a few things he liked, and a few things he didn’t like, and then he said, “pacing is all-important in tall tales.” Tall tale?

Now here’s an embarrassing admission: I never thought of my story as a tall tale. Exaggerated? Embellished? Fanciful? Well, yeah — that’s the way we told stories in my family. But a tall tale? Like Paul Bunyan and Babe the Blue Ox?

And then it seemed so obvious. I must’ve groaned then. Of course “The Dirty Cowboy” was a tall tale!

So I decided to take the rejection as a challenge.

excerpted from this article

Features Of Tall Tales

Tall tales are a classic form in Australia. If you travel in the outback, you’re likely to come across an old man who is particularly good at telling yarns. If he’s really good (and it’s often a ‘he’), he’ll have you believing him right up until the end, when he’s ‘gotcha’.

For an example of such a tale, listen to a master. This bloke (‘Bongo’) rang into an Australian radio station cracking on his story is true. If it’s true, I’ll eat every single one of my hats. Go to episode 404 of Mysterious Universe and, unless you want to hear all about sleep paralysis and trolls sitting on chests (which is also fascinating), you can skip straight to Bongo’s yarn at 51:25. Strange things happen in the Outback.

THE SHAGGY DOG STORY

A type of tall tale is the ‘shaggy-dog story’. In its original sense, a shaggy dog story is an extremely long-winded anecdote characterised by extensive narration of typically irrelevant incidents and terminated by an anticlimax or a pointless punchline. They are designed to entertain. They’re not famous for being elegant or realistic or psychologically insightful.

Shaggy Dog stories are also known in some Internet circles as ‘feghoots’. A feghoot is described as a short-short story (300 words on average, although 500-word examples exist), ending in a pun or a punchline that is pretty obviously the only reason for the story’s existence. The telling detail in a Feghoot is the groan emitted by the reader/listener when he hits the punchline. In essence, the feghoot is an Overly Pre-Prepared Gag in short story form. The Feghoot is named for the character Ferdinand Feghoot, created by Science Fiction author Reginald Bretnor using the pen name Grendel Briarton. Bretnor chronicled Feghoot’s adventures in the multi-year series “Through Time and Space with Ferdinand Feghoot!”, in which each instalment was a short-short that ended in a horrific pun. When it’s told by an oral storyteller it tends to be called a shaggy dog story. When a science fiction writer does it, like Isaac Asimov or Arthur C. Clarke, it tends to be called a Feghoot.

Tall Tales In Picturebooks

Intended to dupe the listener, tall tales are particularly associated with the U.S. frontier, although some other cultures (such as Australia) have similar stories. Tall tales rely on a delicate balance between sober narration and corny exaggerations. American tall tales possess the very essence of the American spirit, complete with the outrageous feats and daring heroes. Stories of famous tall tale heroes, such as Paul Bunyan and Mike Fink, were originally passed along through the oral tradition of storytelling. Picture book examples are Paul Bunyan: A Tall Tale (1984), illustrated by Steven Kellogg: and Dona Flor: A Tall Tale About a Giant Woman with a Great Big Heart (2005), illustrated by Raul Colon. Some tall tales are based on people who actually existed, such as John Henry (1994), illustrated by Jerry Pinkney: and Casey Jones (2001), illustrated by Allan Drummond. There are several original stories that build on tall tale motifs, including Library Lil (1997), illustrated by Steven Kellogg: Swamp Angel (1994), illustrated by Paul O. Zelinsky: and The Bunyans (1996), illustrated by David Shannon.

A Picture Book Primer: Understanding and using picture books by Denise I. Matulka

Dr Seuss loved Tall Tales. See And To Think I Saw It On Mulberry Street.

Tall Tales In The Classroom

Tall tales are very fun to write and free the imagination to perhaps go on to write something a little less fanciful later.

I once had a Year 8 relief teacher called Mrs Bray [insert unfortunate donkey pun], who actually did a much better job of teaching than my regular teacher, who really wanted to be a young adult novelist (and later achieved publication). Despite the fact Mrs Bray got lots of grief for not being ‘our proper teacher’ I secretly regretted that she didn’t stay on full-time.

She had us write a tall story once, and for some reason, I have kept it. Here it is:

TALL TALE by me, aged 10 or 11.

I began on a Tuesday, because it wasn’t raining. Since I hadn’t enough money to go anywhere I thought I’d dig a hole to China. It took me about half an hour and when I got there, a whole lot of Chinese people ran up to me and attacked me with chopsticks. [This little bit of xenophobia earned me two ticks in the margin.] I flipped over them and ran to the Space Centre where I jumped in a rocket and flew to the moon. The brakes didn’t work and I was about to crash. It didn’t matter because the cheese was soft. I ate some, then flew back to earth. I landed in a desert and to get back home I had to cross water. I got some helium which managed to survive the crash and inflated a camels [sic] humps. I held on to its legs and told it to float to New Zealand or else I’d chew its toenails off. He told me he had no control over which way the wind blew and we ended up on the clouds. They were bouncy, like a trampoline. I slid down the north pole and landed on top of an igloo. The Eskimos [see above] were nice people [redeemed] who invited me in for tea. We had some Maggi soup. [‘soup’ made out of powder and boiling water, for the unlucky uninitiated] Then I swum [sic] to New Zealand. By then it was dark and I couldn’t see where I was going, but finally got home where Mum sent me to bed. But a monster peeked in the window and I hit him over the head with my bed. We had monster sandwiches for weeks afterward.

THE END

Great tall story!! [in red teacher biro]

It’s rather disturbing how well I managed to fill that brief.

WRITING YOUR OWN TALL STORY

Here are 30 other ideas for teaching writing, from National Writing Project

Tall tales, as well as the subgenre of shaggy dog tales are so important to Australian culture there is an Australian series called True Story with Hamish & Andy in which real-life shaggy dog stories are re-created by actors.

Children’s books play a lot with size as a form of exaggeration, from Giants and Ogres as oversized people, to oversized moons to indicate an eerie, magical environment, almost every kind of children’s story plays with scale in some way.

AUDIO EXAMPLE OF A SCARY TALL TALE

First, listen to a master. This bloke (‘Bongo’) rang into an Australian radio station cracking on his story is true. If it’s true, I’ll eat every single one of my hats. Mind you, the guys at Mysterious Universe believe it. Strange things happen in The Outback.

What do you think?

Go to episode 404 of Mysterious Universe and, unless you want to hear all about sleep paralysis and trolls sitting on chests (which is also fascinating), you can skip straight to Bongo’s yarn at 51:25.

No doubt about it, Bongo is a master of the form. I bet he’s been telling this very yarn for years and years (since September of ’78). If you go to the Australian Outback you’ll meet a number of great storytellers just like Bongo; my in-laws love their camping holidays and they’ll tell you exactly where to find these old guys – out near Lightning Ridge and so on. There’s nothing much else to do out there after dark, you see, with no internet connection and no nothing. Spinning yarns while sounding authentic is a valued skill, like playing the banjo or the harmonica… or the Bongos, even.

- This old fella spins a tale just like my Dad spins a tale. He doesn’t want to come across as a master of the form – despite the fact he is – so he goes into all this extra detail (just like my father does), about who was where and what the roads were called and just when you start wishing he’d get on with his story, there you are: he’s come to his point.

- I can’t believe a Telecom truck wouldn’t give this guy a ride back into the nearest town. The overwhelming majority of people you’d meet in remote areas would be happy to give you a lift back. Notice the truck driver winds his window down just ‘a crack’. He’s scared of something, but won’t say what. Great tension building there.

- The Thing that rips the door off its hinges is – judiciously – left entirely to the listener’s imagination. Bongo is so scared of this thing he can’t describe it. He’s got the stutter and the fake whimpering down to a fine art.

- I love the climax of this tale. The Thing has ‘a fetish for white, skinny, hairy legs’, and has them draped all round the place. By this point, the storyteller can tell he’s got you – or not – because his audience will either crack up laughing or listen, deathly quiet. I must say, this scene reminded me a little of Wolf Creek, one of the scariest movies I’ve seen, and which has a similar plot, of getting lost in the Australian Outback and meeting a crazy fetish murderer.

- Bongo cracks on he’s been in a psychiatric ward – has been ever since the incident 32 years ago. Well, that was a nice touch. Not something we can all get away with, though some of us might.

A NON-TALL TALE OF A TALL TALE

One of my best memories of first-year teaching involved me telling a scary tale to a group of 14 year old girls. After the older teachers went to bed, I stayed around the campfire and scared them half to death with a tale I no longer remember. We were on a Duke of Edinburgh tramp and were camping overnight in the middle of a National Park surrounded by dark forest and the sound of the river and I must say, 14 year old girls make a wonderful audience. I learnt a lesson that night – even after I’d joined the other teachers in the cabin on the hill, we listened for hours to screaming and giggling as they revelled in further scary tales of their own. None of them got much sleep. The next day, we were supposed to climb a steep hill and it was damned hard work trying to get them up it. Eventually, I lost the game because the laziest bunch of them decided to just sit down. The others joined them.

“That’ll serve you right for getting them all worked up with scary tales,” I was told.

A few years later I was supply teaching near London, and I learned that the ability to spin a good scary yarn at short notice is a good skill to have, when you’ve a room full of kids and nothing much else but an hour to fill.

Again, my best memory from that time involves a scary tall tale – maybe the same one – I don’t remember. I was having trouble with a bunch of 12 year olds – they wouldn’t sit still and listen to a darn thing, so I sat them on the floor in a circle, asked them to imagine a camp fire and turned out all the lights. (Being London, it was a dark, grey day.)

I was almost at the climax of my tall tale when the whole lot of them screamed prematurely, scaring even me. A head had appeared through that little window you often find in a classroom door. In the semi-darkness it was a freaky looking thing indeed.

It turned out to be their PE teacher – a huge guy with a head of wild dreads, and he’d come only to deliver a message about an after school football tourny.

He wondered what the hell I was doing in there.

Anyway, if you work with kids, you need something – just one thing – that’ll impress them. Maybe you can do tricks with a soccer ball or pull out a guitar and crack out a tune. If you can’t do any of those things, I highly recommend mastering the art of the scary tale. It’ll get you some respect.

Trust me.

FURTHER READING

The Cremation of Sam McGee BY ROBERT W. SERVICE at Poetry Foundation

RELATED TERM

Jack tales: Often referred to as tall tales because they expand the bounds of reality and believe.

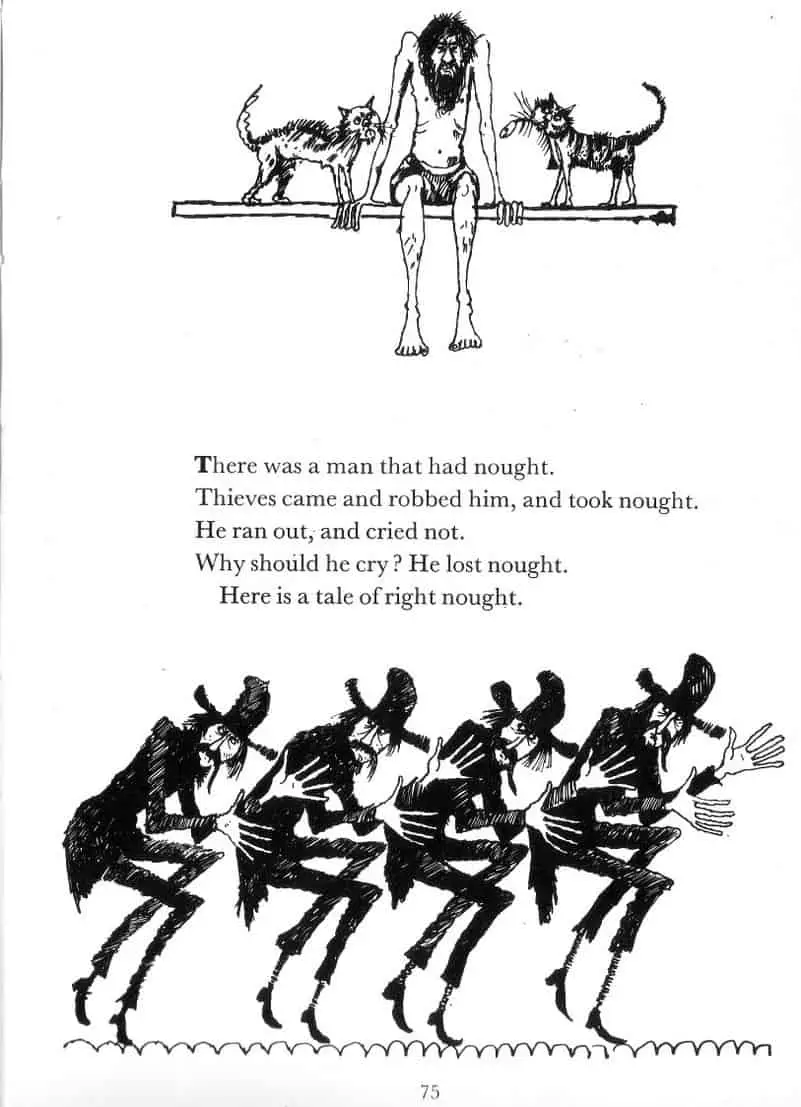

The catch tale is a formulistic framework in which the manner of the telling forces the hearer to ask a particular question, to which the teller returns a ridiculous answer. There’s a long history of catch tales in folk tale. See the CATCH TALES entry from Baughman’s Type and Motif Index of the Folktales of England and North America by Ernest Warren Baughman 1966.

In a subcategory of the Catch Tale, the joke on the listener. The story-teller tricks the listener with an ending which is eithe~ unexpected or pointless, or hoaxing.

e.g. Person loses item of jewelry in stream. Next year he catches a fish, asks listeners what they suppose was in the fish. They suppose the missing jewelry is there. Teller: “Guts.”