Founding editor of The Onion wants to help with the job of learning the write comedy. Stephen Johnson argues that every joke falls into one of 11 categories. At first glance this sounds like the ‘Seven Basic Plots’ idea, which is a pretty unhelpful way of looking at story if you’re harbouring hopes of telling one — forget whether there’s some elemental truth to it or not. That said, I am a fan of The Onion — they get humour right the vast majority of the time — so I decided to take these eleven categories and apply them to some popular humorous children’s books. Is Scott Dikkers right? Are there really only eleven categories of humour.

Also, can we apply these same categories to humour written for children?

There are no lengths to which humorless people will not go to analyze humor.

Robert Benchley

Humor is just truth, only faster!

Gilda Radner

So, why analyse humour?

I’m pretty geeky about comedy and am forensic about what makes a joke work, so I’m able to put things in my books that I won’t find funny but can be confident others will.

Maz Evans via Charlotte Eyre’s publishing newsletter

By age seven, children begin to appreciate language play such as riddles, puns, and jokes as they develop the ability to restructure mentally events and objects in novel ways and begin to understand reversals, double entendre, and the different perspectives of characters.

Playing with Words, “Dav Pilkey’s Literary Success in Humorous Language

1. IRONY

First, a refresher: What even is irony exactly? The Onion’s definition: Intended meaning is opposite of literal meaning. Honestly, I’m sure from the outset — if a joke doesn’t fall into any of the other categories, the definition of ‘irony’ is so broad that I predict it can be shoved into this one.

Humour often lies in the gap between what is said and what is meant. […] In relaxed, friendly talk, speakers collaborate in talking about one thing while meaning something else, thus maintaining a play frame.

I’ve heard it said that we can’t rely on children to pick up irony until the age of about 8, though that has recently been revised right down to about 3. This may say something about our heavily ironic culture.

The thing about children’s books is, we never know the exact developmental stage of each individual reader, so there’s always a chance irony will be taken literally. On the surface this doesn’t matter. If the kid doesn’t get the joke they don’t get the joke, right? But what if ‘not getting the irony’ means seeing straight up sexism/meanness/racism or something like that? We need to be careful here, especially when it comes to ‘hipster irony’ -ie. being mean, but not really being mean, because everyone knows we’re not mean people, right?

This irony thing is important because a lot of children’s stories (especially films) are written with the ‘dual audience‘ in mind, especially in film and in picture books, where the adult is sitting alongside the child.

- Rosie’s Walk is the classic example of a picture book demonstrating an ironic distance between picture and text. The words say something completely different from the text. Today there are many more examples of ironic distance in picture books.

- In A Long Way From Chicago, the grandmother is a comical character but the humour is often understated irony which involves nothing more than our narrator pointing it out: ‘She said she never slept but she had to wake herself up to go to bed.’

- Dramatic irony is describes a gap between what the audience knows and what the character knows. Sometimes the audience knows more than the character. This kind of dramatic irony is called ‘reader superior position’. In The Seriously Extraordinary Diary Of Pig, Pig sees a funny looking farmer at the fair. From the illustrations, the reader understands immediately that this is no farmer. She looks like an archetypal villain. But Pig simply says, “She is the most ugly farmer I’ve ever seen” and describes an archetypal villain without putting two and two together himself. Then there’s reader inferior dramatic irony. This is less useful in comedy, but is especially common in certain genres such as heist, where the audience is constantly two steps behind the characters and their plans.

- Another excellent example of dramatic irony can be seen in I Want My Hat Back by Jon Klassen. The reader sees the red hat long before the main character does. The younger the reader, the more you should make use of reader superior irony. Young kids are still working out the world and they need to feel smart. I can’t think of an example of reader inferior irony in humorous picture books.

- In a story with no pictures, dramatic irony can come from an unreliable narrator, who is not telling the reader the full story. This might be because they don’t understand what’s going on. (But the reader does.) Unreliable narrators are useful for many reasons, and sometimes, in the hands of an expert storyteller, can lead to humour.

Less specifically, ironic jokes would include:

- A character tries to fix something but ends up making it worse. For instance in the We Bare Bears pilot a spider hanging from a tree is dealt with by kicking the tree. Hundreds of other spiders fall down from the tree. Ironic because the character aimed for one result but got the (exaggerated) opposite. (Irony combined with hyperbole.) Oliver Jeffers uses the same combo in Stuck.

- In teen stories irony is often sarcastic.

2. CHARACTER HUMOUR

Comedic character acting on personality traits

In order for this to work, the audience needs to think in terms of stereotypes or, more kindly, in terms of archetypes. Alternatively, the audience has to know (or feel they know) a character so well that they are able to think, “How very typical of [Character].”

- In the Wimpy Kid books, the older brother Rodrick is set up as a dimwit but every now and then he says or does something really smart. This is both a ‘character’ and an ‘irony’ joke.

- We feel we know Pig The Pug as soon as we meet him — he is the kid who hogs all the toys. We love it when he gets his just desserts.

- This Moose Belongs To Me by Oliver Jeffers relies on the reader identifying the boy in the story as a self-involved bossy pants.

- Scarface Claw by Lynley Dodd is an archetypal villain but with a soft side. This relies on irony as well as character humour.

- Z Is For Moose stars a moose who has a meltdown because he isn’t given the opportunity to be the centre of attention for a minute. The stereotype is familiar — the narcissist stage actor.

- In The Extraordinary Diary of Pig, character humour comes from a pig doing human-like things with his pig’s body, e.g. crossing his trotters for luck. This kind of humour is common in humorous stories featuring humans in animal bodies, and is one of the reasons animals are so often used instead of people in children’s stories.

- Some character humour can tip into plain meanness. In Dog Days (Wimpy Kid series), Greg goes to the local pool and notes in his diary that someone should tell one of the neighbourhood women not to wear a swimsuit at eight months pregnant (due to its being too grotesque). While a kind reader puts this down to Greg’s character flaw — he is on the verge of adolescence and terrified of adult bodies, including the hairy bodies of the men in the changing room — this kind of humour matches (and models) schoolyard body shaming and bullying. I prefer to avoid books with this kind of humour. Which leads to the problem: If you want to write a mean-spirited character, how do you do it without promoting/triggering unpleasant memories of mean-spiritedness? It’s a fine line. Bear in mind that Jeff Kinney originally wrote Wimpy Kid for adults, aiming for a Wonder Years type story. It was his publisher who repurposed it for children. Meanspirited but funny characters are a surefire hit with kids, who see far more insulting interactions in their day at school than any typical adult.

- In children’s stories as well as in playground chants, teachers and other adult figures of authority are often the butt of the joke. In a picture book such as The Book Without Pictures by B.J. Novak, the joy comes from hearing the adult reader saying ridiculous things.

3. REFERENCE HUMOUR

Common experiences that audiences can relate to

Romantic Rejection. A lot of the Wimpy Kid humour is about rejection from girls that Greg Heffley sees as potential girlfriends.

Parental Wishes Conflicting With Child Wishes. The Wimpy Kid stories are also about the conflict that arises when you want to play on your computer all day in your own room but your mother wants you to do family bonding exercises and force you into ‘fun’ activities that are fun for her but not for you. A lot of adolescents can surely relate to this. Less specifically, kids can really identify with lack of freedom.

Obviously, stories for toddlers and preschoolers must refer to experiences shared by children of that age.

- Chatterbox is a familiar story about waiting and waiting for a baby to learn to talk, then wishing they’d shut the hell up as soon as they start.

- Harry The Dirty Dog plays on a childhood dislike of baths.

- Z Is For Moose is funny because we’re watching a toddler (Moose) having a massive tantrum after being left out of a show.

That said, picture books sometimes appeal to a distinctly adult experience. Mr Chicken Goes To Paris relies on the incongruity of a large chicken doing all the typical touristy things in Paris. Adults will recognise the type of holiday, as well as the tedium of sitting through someone’s photos of it. The story’s interest comes solely from the fact that our tourist is a big chicken. This is hat on the dog type humour and because adults identify with the experience of tourism, Leigh Hobbs appeals to a dual audience.

Another type of reference humour is cultural. In the pilot of We Bare Bears, the brown bear (Grizz) suggests that the panda knows kung-fu, something he has in his favour when it comes to dating. The panda says that actually he does not know kung-fu. We are thus reminded of the Kung-fu Panda franchise of children’s films from DreamWorks. We feel ‘in’ on the joke for getting that cultural reference. Grizz’s comment is also funny because we recognise he is relying on stereotypes. It’s the fictional equivalent of people with Asian faces and glasses always being asked if they’re good at maths.

A similar joke is used repeatedly in the British comedy series Fresh Meat, in which other characters assume Howard is a Lord of the Rings fan because he is a nerdy type who looks like he’d be schooled up on the finer points of high fantasy. As Howard keeps insisting, he’s never even read Lord of the Rings, and has no interest in reading it. He gets increasingly irritated by accusations of having read it. This is a triple layered joke: (cultural) reference + character humour + irony.

When a story makes a cultural reference to itself, it’s now called a ‘callback‘. This relies on the audience having seen earlier episodes of the show. Each Simpsons episode has about 10-20 callback jokes in it, counted separately from other cultural references, which are even more numerous. Groups of friends cement friendships by swapping injokes that only those friends would get. Callback humour is how you get yourself a fanbase.

The converse of reference humour would be the non sequitur, a feature of absurdist/surrealist humour. The audience is exposed to situations they’ve never experienced before themselves. I wonder if this form of humour is not included in The Onion List for the reason that modern audiences don’t find absurdist humour laugh-out-loud funny. This is the humour of Edward Lear, Alice In Wonderland, Waiting for Godot… It’s clever, it can be interesting, it can highlight important political truths, but is it still funny? More recently, works such as A Series of Unfortunate Events and Far Side comics have been described as surrealist, so perhaps surrealism has not died, but evolved.

The humour in children’s literature is common to sitcoms for adults. The same rules apply. Characters feel awkward or humiliated. It’s difficult to think of comic heroes who don’t have significant flaws. Georgia Nicholson is obsessed about her looks, a little bit selfish, mean to her friends. Greg Heffley is that as well. You would think this is a reason not to like these heroes but in fact children relish these portrayals. They like finding their own shortcomings in comic heroes. [Do these flawed heroes really remind adolescents of themselves? I suspect that would feel too cringe-worthy to enjoy. I suspect they see their friends and school enemies in these characters rather than themselves, but I’ve yet to read research on that.]

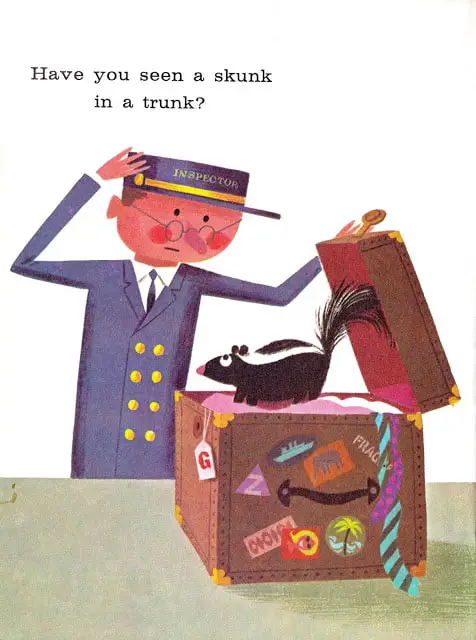

4. SHOCK HUMOUR

Surprising jokes typically involving sex, drugs, gross-out humour and swearing

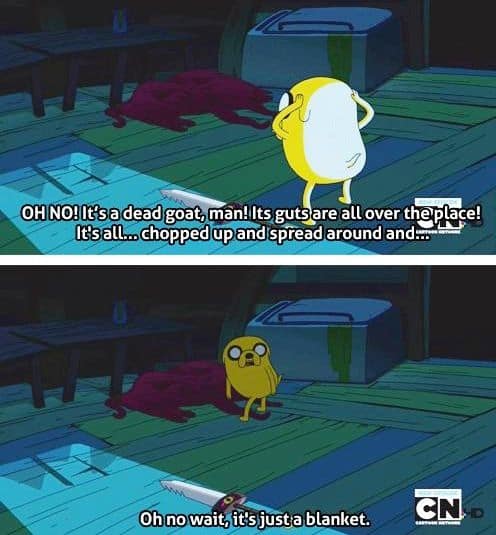

How to get away with more shocking things in comedy for kids? One popular trick: Make it look terrible at first but the reveal is that it’s benign.

Something common in children’s stories but less common in adult stories: Bum jokes and gross-out humour (poo, vomit, snot and other bodily excretions). For adults gross-out humour is sexual.

Kids can also be shocked by post-pubescent bodies. The Greg Heffley (Wimpy Kid) example of Greg being disgusted by grown men in the showers (mentioned above) is also an example of gross-out humour. Greg is terrified of his imminently changing body. For good reason, this particular fear is often explored in coming-of-age comedies. Morphing into an adult is terrifying.

The Disgusting Sandwich is a picture book for young readers and a very mild form of gross-out humour. The humour of this story relies on the shared experience of dropping food on the ground but still sort of wanting to eat it.

The Mole Who Knew It Was None Of His Business is another fairly tasteful example of a story about poo, and is made more tasteful by the use of quite literary language and the German language onomatopoeia. The poo itself does not feel disgusting because of the countryside setting. Wholesome poo.

For slightly older kids (pre-adolescence is the golden age of gross-out humour), we have the work of Andy Griffiths, e.g. The Day My Bum Went Psycho and a whole raft of similar stories from the same Australian author.

Most humour has its origins in bad taste. Then, when the joke’s been done enough times, it no longer has shock value. The shocking thing has become part of the culture. This primitive side of humour comes out of aggression and fear, and is a way of dealing with that. This explains why comedians often go beyond the line of acceptability. Perhaps, like me, your favourite comedian offends you sometimes. The comedians don’t know where that line is either, because it’s constantly shifting. The comedian’s job is to find that line. That’s their raison d’etre. They inadvertently cross it from time to time, so we all know where it is.

5. PARODY HUMOUR

Mimic a character, trope, genre as closely as possible

This type of humour relies on your audience having sufficient experience in the original character/trope/genre itself that they recognise the parody. Along with irony, parody might therefore be lost on the youngest readers. In the past I have written about popular ‘children’s films’ which should probably more accurately be described as films for adults or adolescents due to the advanced irony — which ordinarily might float on by younger audiences without consequence, but may convey pretty disturbing messages when taken at face value. Children (and adults) tend to assume that animated film and claymation is for children, but that’s no longer the case.

Genre Parody

The 2012 film ParaNorman relies on the audience’s understanding of the zombie horror genre. Or, we might be expecting a Cinderella story, for instance, but the character ends up even poorer than they were before. Or, as Babette Cole wrote in Princess Smartypants — we might be expecting the princess to find her prince charming, but she decides in the end to remain single, upending the classic romantic fairytale. This joke is a kind of cross between ‘misplaced focus’ (we’re thinking this is a love story) and ‘parody’ (of the archetypal love story).

That Is NOT A Good Idea by Mo Willems defies our expectation of a fable in which the duck gets eaten by a wily fox. It’s a parody of a fable, though also a form of irony — we don’t expect the cute little duck to be so wily. An understanding of Aesop comes in handy here, too. Aesop set up the animal character tropes for us and we’re still using them and subverting them to this day.

Character Trope Parody

The Fantastic Mr Fox film relies on the audience’s understanding of a stereotypical 1950s breadwinner father, as well as the dominant culture’s fictional nostalgia associated with that period. The first generation of readers who grew up with Fantastic Mr Fox are now my age — middle aged. The 1980s was The Golden Age of Roald Dahl. This film is mostly for them.

6. INTENSIFICATION AS HUMOUR

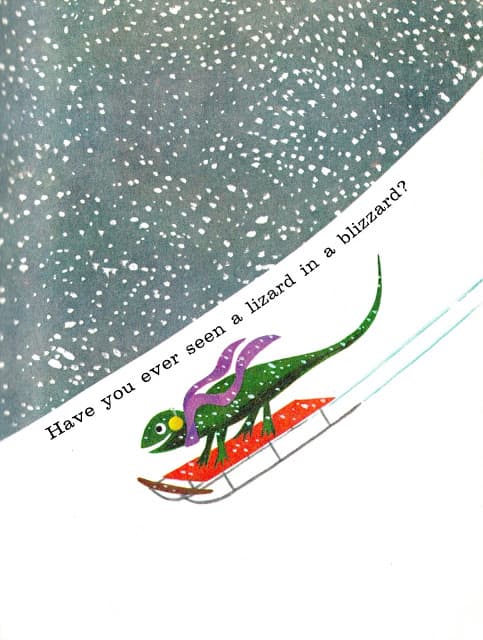

Exaggeration to absurd extremes

Unlike irony and parody, this type of humour is safe for the youngest of audiences. Hyperbole is super common in picture books, and almost mandatory in funny carnivalesque picturebooks. Hyperbole is a subcategory of intensification, but intensification goes beyond hyperbole.

- Stuck by Oliver Jeffers is an excellent example. There’s no way all those things would get stuck in a tree. Jeffers knows how to take a joke to its conclusion. This book is a masterclass in hyperbole.

- The Biggest Sandwich Ever features a massive sandwich followed by a massive dessert — everything in carnivalesque oversize.

- The Cat In The Hat by Dr Seuss is perhaps the stand-out example.

Hyperbole or intensification can be achieved using all of the following devices, which are all commonly used across funny middle grade graphic novels in particular:

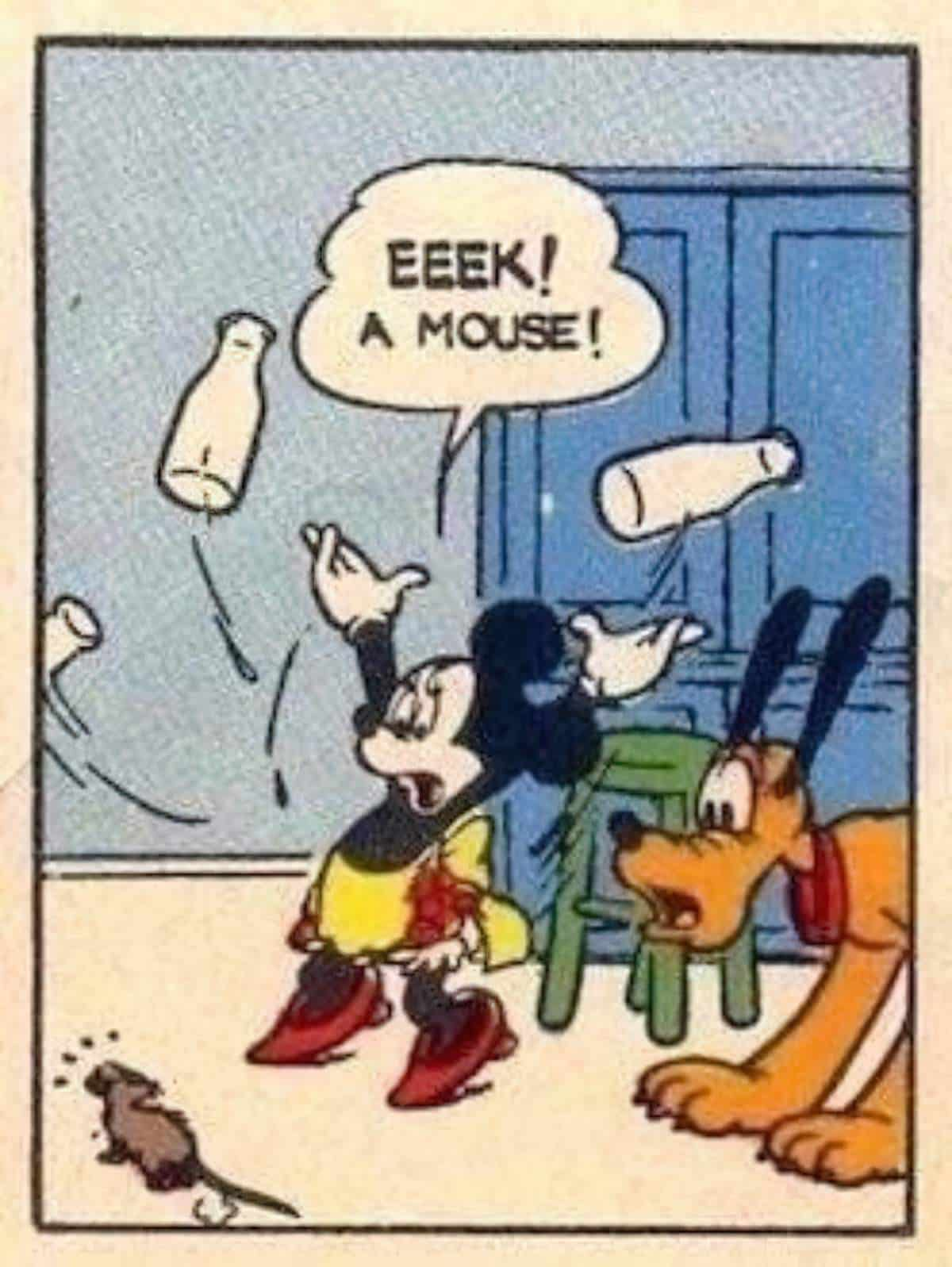

- Creation of sounds in exclamations (included as ‘intensifications because they are typically disproportionate to the degree of shock, dismay, or surprise expected from a reaction to an event).

- General sound play (onomatopoeia, alliteration, and assonance)

- Palindromes (words, phrases, or sequences that read the same backwards as forwards e.g. poop)

- Increased stress on words and meanings (word redundancy, word repetition)

- Figurative language (idioms, similes, metaphors)

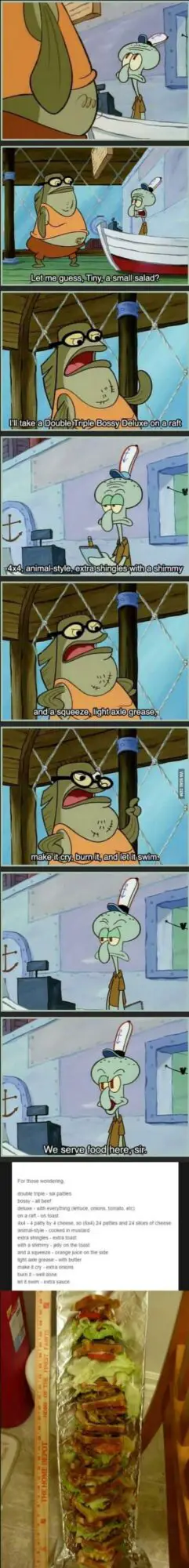

- Synathroesmus (the piling up of words, usually adjectives e.g. “gigantic, gooey, robotic fingers”)

- Textual emphasis (capitalization, italicization, extra large font)

- Exuberant expressions (grandiosity, exaggeration)

- Logical impossibilities

- Repeated phrases which function as running gags (e.g. “Truth and Justice and all that is Preshrunk and Cottony!”)

Melodramatic Humour

Melodrama comes under the category of hyperbole. Melodramatic characters are sometimes funny because of their uber-pessimism or optimism. (By the way, I usually mean something different when talking about melodrama.)

- Similar to the Squadward scene above, a client of the mother from Freaky Friday (Lindsay Lohan version) is particularly needy. “How’s your day been so far?” asks the daughter in her mother’s body. “Fine. Then I got up.”

Litotes

I’m not sure where to put hyperbole’s opposite: understatement, or litotes. I guess it goes in here.

- The Seriously Extraordinary Diary Of Pig “We don’t want to be handbags!” (Not — We don’t want to be slaughtered!)

- From Spongebob Squarepants: “I don’t want to be peeled! I’m not a banana!” (Ditto)

Understatement often occurs when the main character is near death, but because this is a series we know (and the characters know, in a meta kind of way) that they are not going to actually die. Therefore their reactions to near death are often understated. In the examples above they are unrealistically articulate, for instance, calling to mind the plaintive cry of a toddler who doesn’t want to carry a bag, or doesn’t want to eat a banana.

HYPERBOLIC WORDPLAY

Of course, hyperbole and wordplay often occur together. Hyperbolic language are words or expressions which exceed “the limits of fact in a given context” (Claudia Claridge).

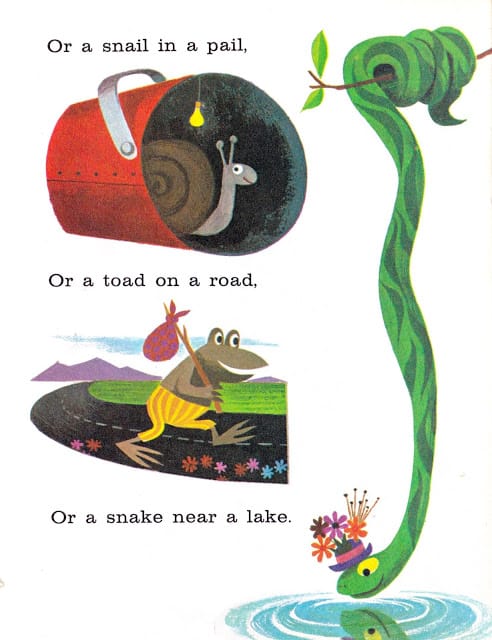

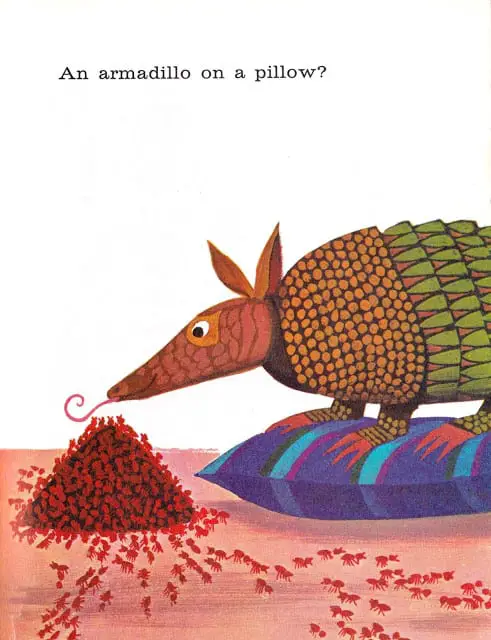

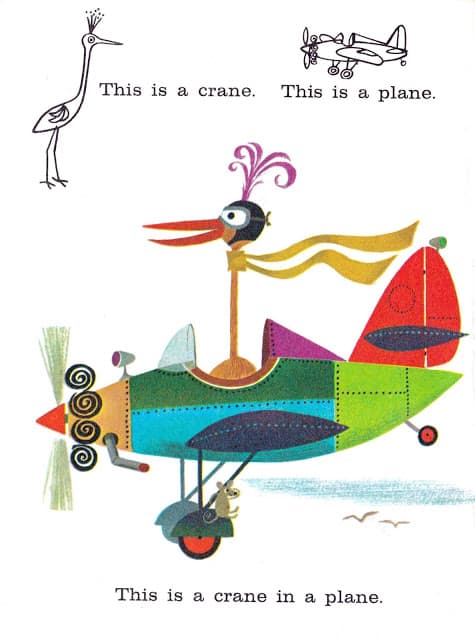

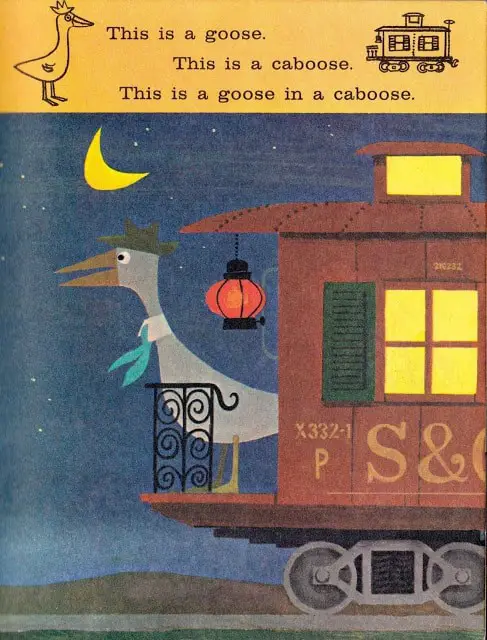

7. WORDPLAY HUMOUR

Puns, rhymes, double entendres, homophones, homographs, nonce formations, portmanteau words, placeholders, baby talk, solecisms, slang and colloquialisms, nominalization, adjectivization, rhyming, ungrammaticality, metathesis etc.

Puns are often simple wordplay for comedic or rhetorical effect.

Both puns and double entendres make use of intentional double meanings. Double entendres are not necessarily puns, though.

A homophone refers to two words which have different meanings but which sound the same. (You get a lot of homophonous puns.)

Use of the same word with different meanings. “Glued to their seats” (engrossed and also literally stuck to the seat with glue)

“A nonce word (from the sixteenth century phrase for the nonce, meaning ‘for the once’) is a lexeme created for temporary use, to solve an immediate problem of communication”. (David Crystal) In literature, an author purposely coins nonce words for poetic or humorous effect, not to solve a communication problem.

A word blending the sounds and combining the meanings of two others, for example motel or brunch.

A word which stands in for another word e.g. thingymajig

A grammatical mistake in speech or writing

The formation of nouns from verbs

A verb turned into an adjective

The transposition of sounds or letters in a word

Children take a special delight in odd or pretty sounds. Given the chance to write, they are very playful with the sonic side of language. Experts say their learning of new words is a process of wonder, laughter, and punning. What children may lack is a developed sense of artistic judgment, so that their poems often include startling successes in sound right next to bland or awkward passages. They tend to accept whatever comes into their heads.

The Poetry Foundation

Between the ages of six and ten we begin to riddles and puns and jokes based on the tricks and confusions of language. The attraction of the riddle is that the person who asks it demonstrates her or his mastery of the ambiguity that is built into language. For instance:

What has four legs and can’t walk?

A table.A riddle can also be a device for proving the other person stupid — in some cases, stupid because he or she takes riddles seriously.

What’s the difference between a mailbox and a hole in the ground?

I don’t know.

Well, I certainly wouldn’t send you to mail a letter.Eventually children learn that words can be used to excuse misbehaviour, and even as a way of trapping a victim into a kind of complicity with his or her persecutor — which is something a lot of adults do with children, getting them to agree that they’ve been bad and deserve a to be punished, for instance. This use of language seems to be behind a familiar catch-riddle:

Adam and Eve and Pinchme went out in a boat to swim. Adam and Eve got drowned, and who was left?

The correct answer maneuvers the victim into asking to be hurt. But there is more to this joke. Its three characters, Adam and Eve and Pinchme, suggest primal, innocent man and woman — or boy and girl — and someone who represents evil, violent impulse, knowledge of good and evil: the serpent in the garden.

As children get older they discover other tricks of language. They become fascinated with tongue twisters, with secret languages like Pig Latin, and with simile and metaphor. Some years ago, for instance, there was a whole cycle of jokes about a character called the Little Moron; the point of the joke was always that he misunderstood metaphors and took them for reality:

Why did the Little Moron throw the clock out the window?

Because he wanted to see time fly.In telling this joke the child asserts that he is not a little moron; he knows what a metaphor is and no longer takes it literally. But the joke also, like a lot of folklore, allows the vicarious expression of forbidden impulses: in this case, the rage children feel when some adult points to the clock as a reason for going to bed, or not having lunch. “No, dear; see, the clock says it’s not time yet.” No wonder the child wants to throw the clock out the window, to make time fly.

Often the mastery of metaphor is used against adults — even against unknown adults. This happens with the telephone jokes that are played by girls and boys when they begin to acquire a more adult voice — or at least the ability to imitate one. They can then spend happy hours calling up numbers at random and saying, for example: “Good afternoon, ma’am. This is the electric company. Would you please check to see if your refrigerator is running?” The hope is that the person on the other end of the line will hurry into their kitchen to check, hurry back, pick up the phone again, and confirm that it is. Then the reply is: “Well, you’d better catch it before it runs away out the door.” If the joke works, the caller has the satisfaction of making the adult follow a child’s directions and look silly.

Alison Lurie, Don’t Tell The Grownups: The subversive power of children’s literature

- Jack and the Baked Beanstalk takes a classic tale and gives it a modern twist. Even the title has been modernised — ‘bean’ is universal, but ‘baked bean’ is comically specific, which I’d actually add as another category of humour. (Comic Specificity.) The story itself is not humorous. (The title may therefore be a little misleading.)

- From A Long Way From Chicago: “The cherry bomb had scared them witless, except for Ernie, who was witless anyway.” More specifically, this is an example of metalepsis — taking an idiomatic expression then turning it into something more literal.

- The whole book of The Seriously Extraordinary Diary Of Pig is written in a naive kind of dialect reminiscent of the speech of Roald Dahl’s BFG (which, it’s worth noting, was based on Patricia Neal’s mixed-up language as she partially recovered from a serious stroke.)

- Symbolic names might also be considered a type of wordplay — i.e. someone’s name is in itself funny either because it’s so apt or so ironic.

- Alliteration can make serious things sound funnier due to alliteration’s usual association with light-heartedness. In The Seriously Extraordinary Diary Of Pig Cow is captured. The villain chants “Mince them on Monday, tan them on Tuesday…” (Do you recognise this joke from The Tawny Scrawny Lion, a classic Little Golden Book?)

- Sometimes the wordplay element forms the entire basis of a plot. In The Incorrigible Children Of Ashton Place, the children have been raised by wolves. Literally.

- Wordplay humour presents issues for picture books (in particular) that could otherwise be translated. There are probably books which cannot be successfully translated, for example funny books which relies on rhyme. The Gruffalo doesn’t really take off outside its English language version [because what makes it so good is its rhyme and rhythm.]

- Mentor Texts for Word Play by Marcie Flinchum Atkins

- Timmy Failure (Stephan Pastis)

- Big Nate (Lincoln Pierce),

- Captain Underpants (Dav Pilkey)

- Middle School, the Worst Years of My Life (James Patterson)

- The Odd Squad (Michael Fry)

- The Wayside School (Louis Sachar)

- Diary of a Wimpy Kid (Jeff Kinney)

- Stink (Megan McDonald, Peter H. Reynolds, and Nancy Cartwright)

- Dork Diaries (Rachel Renee Russell)

- Some language play characterizes the Amelia Bedelia series for grades one to five written by Peggy Parish and Herman Parish and illustrated by Fritz Siebel, Lynn Sweat, and Wallace Tripp

- The nonsensical poetry books of Shel Silverstein, John Ciardi, and Steve Attewell.

The following from Spongebob Squarepants is not only dual audience humour but is also in-group humour, understood only by people from a particular culture. It includes an explanation, for those of us not in the know when it comes to hipster cafes in a particular moment in history and place:

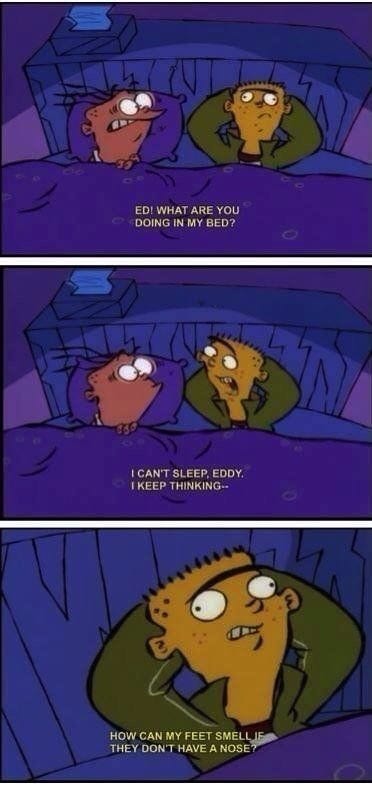

The following gag from another Cartoon Network series, Ed, Edd n Eddy, is childlike humour but no doubt appealed to young adults who know what it’s like to hang out with stoned people:

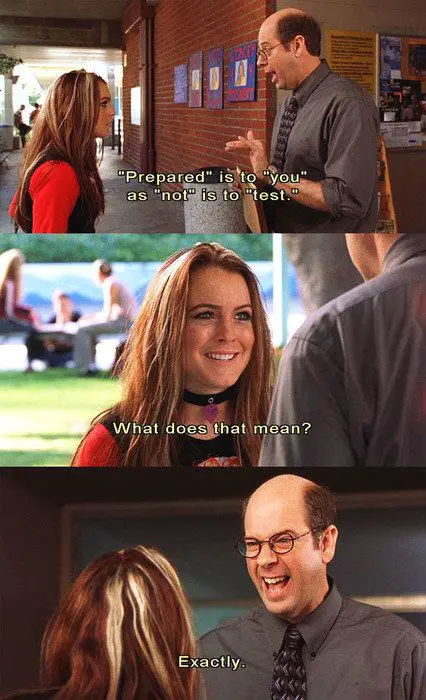

The following example from Freaky Friday appeals to teenagers who are often stuck with the job of trying to decipher their teachers and parents. The words make no sense at all, so wordplay is layered with recognition and also character humour (the teacher is vindictive and has a vendetta).

While it takes on a different form, wordplay is just as popular for a young adult audience.

Even within the category of ‘wordplay’, there are many different types of wordplay, and a joke can work on various layers of wordplay at once, just like any other forms of humour.

Language play at a syntactic—or grammatical—level can be found in Roald Dahl’s statement “I is not wishing to know anything” in The BFG (for the Big Friendly Giant). And language play at a semantic—or meaning—level may include the use of an idiom such as “it’s time to hit the road” used by Mr. Rogers in Amelia Bedelia Goes Camping: Amelia hears Mr. Rogers say it, and she literally hits the road with a stick. Or consider the novel word creation such as the use of “clean-a-rella” for the name of a housekeeping robot in 2030: A Day in the Life of Tomorrow’s Kids, playing off Cinderella who also did all the housework in a well-known fairy tale.

Sometimes language play occurs at multiple levels simultaneously. For example, sound substitutions at a phonological level can change meaning at the semantic level, as in Peter Bently and Deborah Melmon’s portmanteau word “pantachute” (word parts from underpants combined with parachute) in Underpants, Wonderpants.

Other examples include use of puns, as when Lewis Carroll in Alice’s Adventures

Playing with Words, “Dav Pilkey’s Literary Success in Humorous Language

in Wonderland explains that the turtle was called a tortoise because “he taught

us,” and as when the Mock Turtle describes “seaography” school, saying there

they study “reeling and writhing.”

Literary devices used most often by Dav Pilkey fall into two categories of language play— hyperbole and linguistic creativity.

8. ANALOGY JUXTAPOSITION

Comparing two disparate things (perhaps by flipping them completely)

Although Scott Dikkers of The Onion talks about ‘analogy’, when it comes to children’s humour, I prefer ‘juxtaposition’. Analogy emphasises what’s similar; juxtaposition emphasises difference. Similarity isn’t that funny; difference is.

Others — such as Robert Mankoff — have called ‘incongruity’ the basis of humour. There has to be some deviation from the normal. The incongruity can’t be just any old thing — it has to be fitting.

An example: Grandiose titles and language typical of royalty, upper social class, or powerful groups attributed to persons of lower social status or insignificant and inanimate items produce humorous incongruity. (This would also be a type of burlesque humour, because it pokes fun at the upper classes.)

In logic something is either X or not X. In humour, it’s both X and not X.

From an academic paper:

McGhee (1979) proposes that incongruity is a central cause of humor. Indeed, Oring (2010) goes so far as to claim that “humor cannot be appreciated without the perception of an underlying appropriate incongruity” (p. 12). Incongruity humor occurs when an element of a story or situation is established as unexpected, exaggerated, or inappropriate and is then resolved. McGhee (1979) separates incongruity humor into two parts: Discovery of the incongruity and its resolution. In agreement with McGhee (1979), Dean & Allen (2000) state that the two essential elements of a joke are the set-up, which includes the minimum amount of information to establish an initial assumption, and the punch line, a reinterpretation that reverses the initial assumption. Polimeni & Reiss (2006) discuss Veatch’s theory that incongruities in humor must contain one “socially normal” element and one element that violates the “subjective moral order,” or as Veatch defines it, the “rich cognitive and emotional system of opinions about the proper order of the social and natural world”.

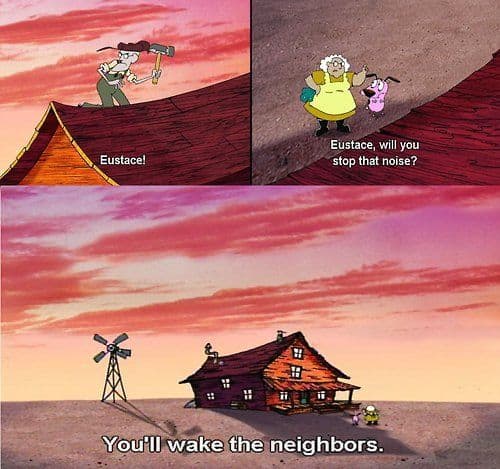

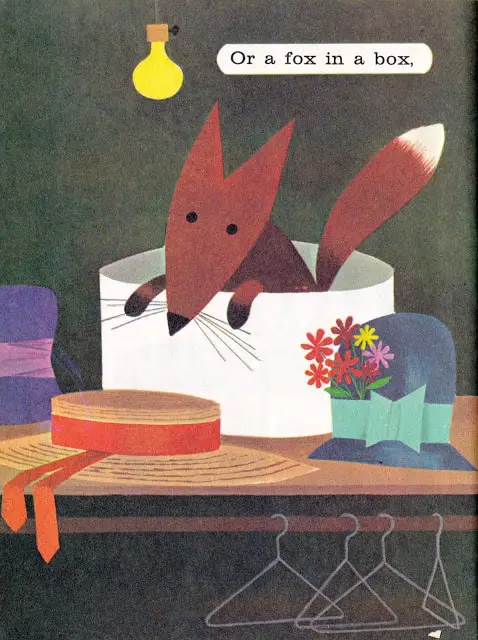

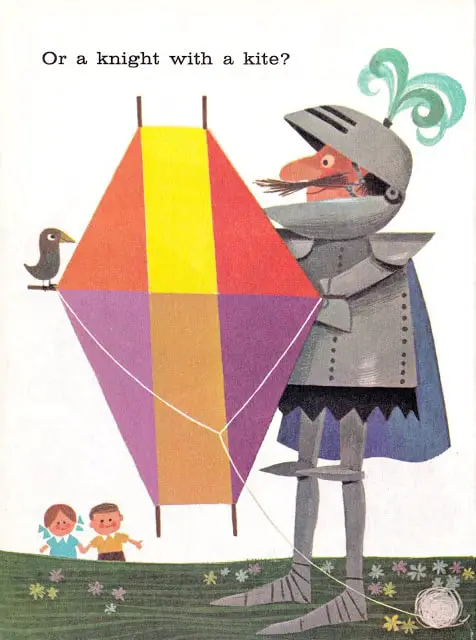

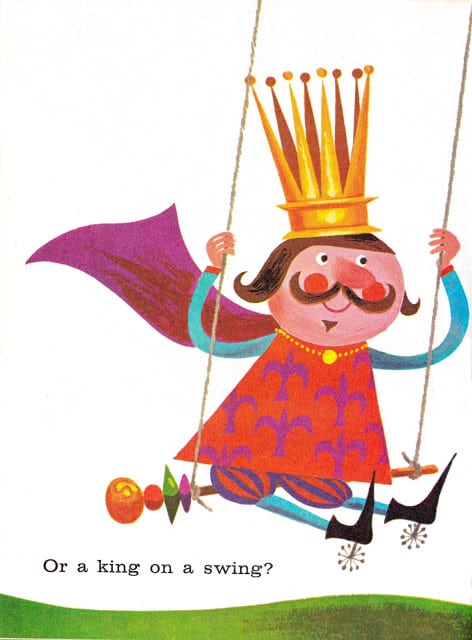

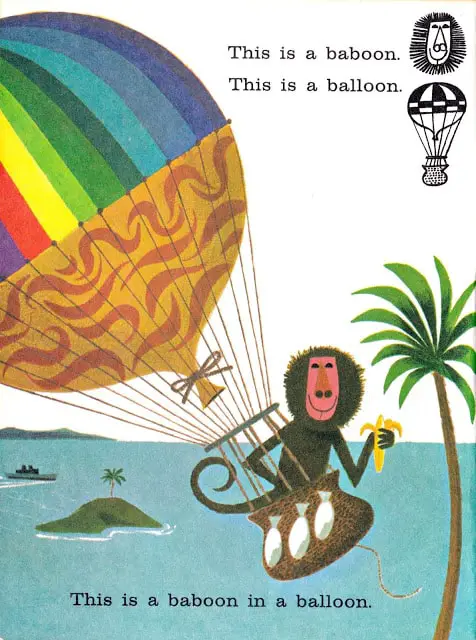

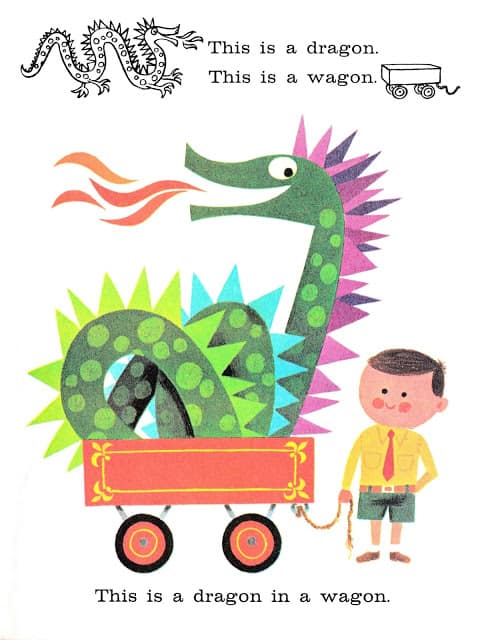

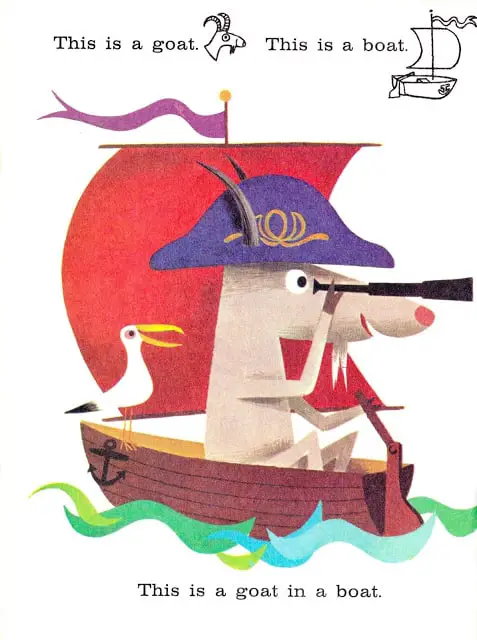

In children’s humour juxtaposition is the ‘hat on the dog’ thing. Putting two unlikely things together. This is why my year three daughter thought it funny when her year three teacher did a cartwheel in the playground — a teacher doing a childhood thing. This was the most newsworthy event of her day.

The Mercy Watson series involves the juxtaposition of a pig in a house — the pig not quite human, but treated as a child. There’s a lot of madcap humour in the Mercy Watson stories, too, since Mercy the Pig loves life. (As you’d expect, there is a juxtaposed character who is dull and no fun at all.)

However, in a lot of stories for a middle grade audience the juxtaposition often involves that old sexist joke of a boy dressing up as/being mistaken for a girl. This is not as benign as the ‘hat on a dog’ joke you’ll more likely see in picture books, as it says something terrible about girls, even when the boy is ostensibly the butt of the joke. At first glance it looks like the boy is the butt of the joke, because he has lost his power owing to behaving/dressing/being mistaken for a girl. But it is girls who lose out here. If being a girl means ‘losing face’, what is that saying about girls? Sometimes it’s not the boy dressed as the girl who is the butt of the joke — sometimes it’s the girly girl getting her comeuppance for being too feminine. Feminine as equivalent for prissy, annoying, swotty and self-absorbed. Too many middle grade novels make use of these jokes.

The Status Flip

First we have the socioeconomic status flip.

Juxtaposing upper class with lower class folk is another source of humour, though only if we’re making fun of the rich people and not the other way around.

In A Long Way From Chicago we have the richest woman in town talking to the most down-to-earth, spade’s-a-spade woman in town:

“What a nice, moist consistency your pie filling has, Mrs Dowdel. I’m sure it will be noted. How much water did you add to the mixture?”

“About a mouthful,” Grandma replied.

This is a nice bit of character humour (the characters have already been established — Grandma is anti-pretention, say-it-like-it-is). It is also funny because of the (possibly intended) image of a hillbilly grandma spitting water into the pie, later meant to be eaten by important people. A similar gag is used in The Help, by Kathryn Stockett. In American stories, pies are good for hiding things in because they look delicious and benign. That particular joke is an example of juxtaposition of class combined with character humour and a bit of gross-out humour, too.

The following gag from The Simpsons might be Bart being a smartass, flipping the insult from the bullies, but he may also be oblivious to a classic wind-up line:

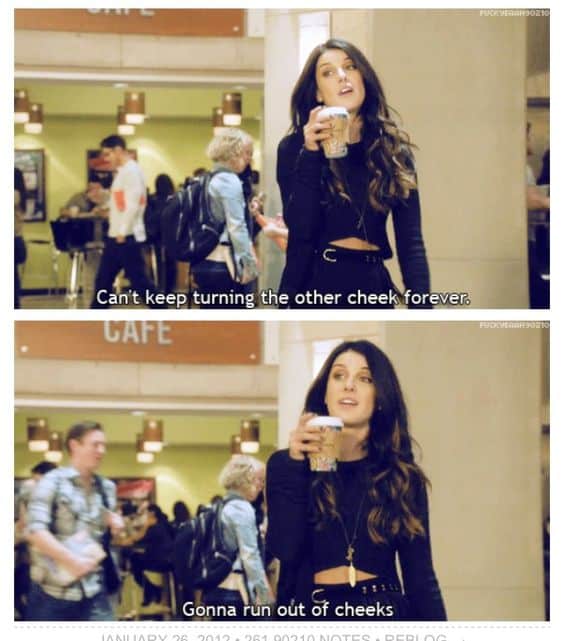

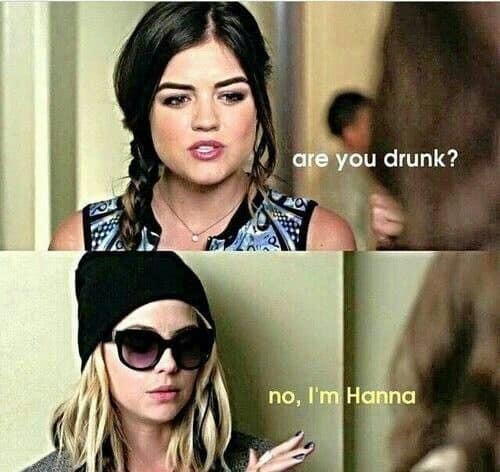

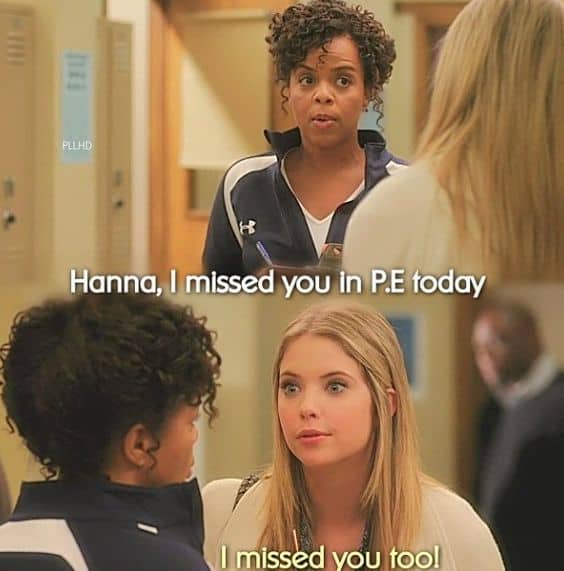

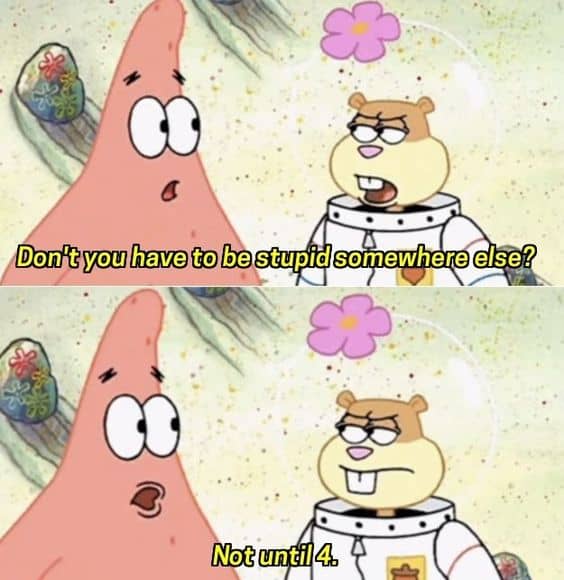

This kind of joke works well in stories for teens when it’s being used as a deliberate evasion. Hanna is that smart ass character in Pretty Little Liars.

Is Hanna a smart ass or is she the stupid blonde trope, pitted against the smart brunette? It depends. The writers use Hanna as they see fit.

The Child/Adult Flip

This is the humour utilised in every single carnivalesque picture book ever written. (Okay, only the funny ones — not all carnivalesque stories are comedy genre.)

In the pilot of We Bare Bears, the bears with adult male voices turn out to be more enthusiastically childlike than the actual children at the party, who are only wearing their party hats ‘ironically’, so they tell us. In other words, the adult/child relationship has flipped. This is common in children’s stories. Oftentimes it’s the grandparents or the father who is shown to be less responsible and knowing than the child, who is then charged with saving the day. The antics of this older person themselves are designed to be funny, partly because old people are thought by children to be staid and lacking in movement.

Here’s Hanna again, flipping status with her gym teacher. She’s using irony but the irony works because of the status juxtaposition.

Boss Baby by Marla Frazee is an excellent example of an adult/child status flip.

The Book With No Pictures by BJ Novak is also an example of a status flip.

The Classic Trickster Flip

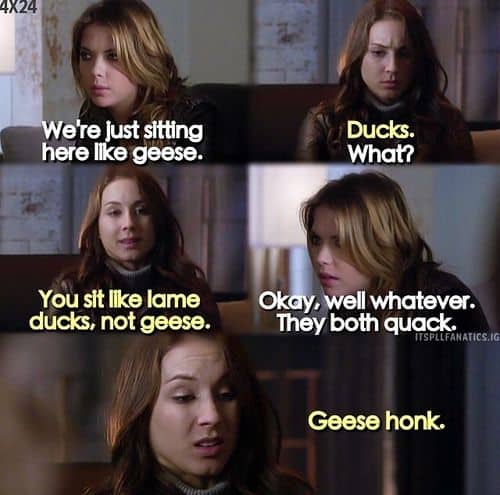

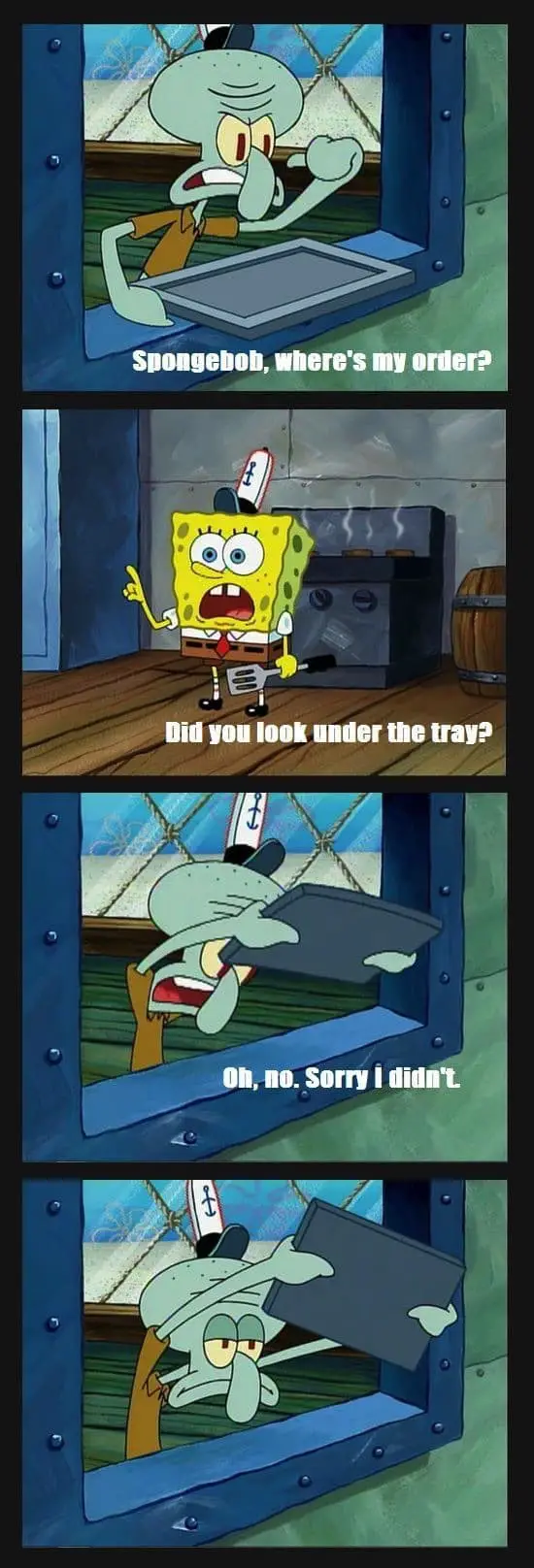

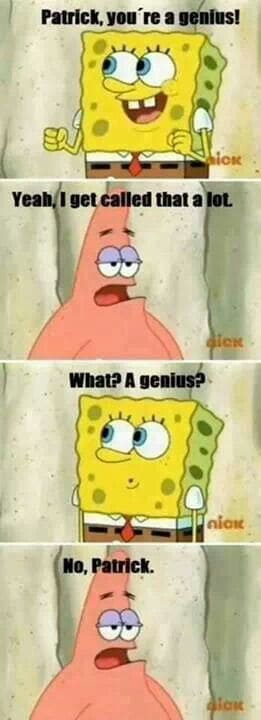

I don’t know what else to call this gag from Spongebob Squarepants:

9. MADCAP

Crazy, wacky, silly, nonsensical

Madcap is another common feature of the humorous carnivalesque.

As I said, with young kids, ‘putting a hat on a dog’ is enough to tickle their sense of humour.

What if you dress up an animal and put them in a house? Is that still funny? When Beatrix Potter created Peter Rabbit, that had not been seen before. Potter’s animal stories aren’t overtly humorous, but would have delighted audiences at the time. Do children still see dressed up animals as funny? I will argue that no, they don’t. That’s not to say animals dressed as humans don’t hold their interest, because they obviously do. An animal behaving as a human says to the kid, “Hey, this story is probably for you!” There are many reasons for writers of children’s books using animals as stand-ins for humans. As for ‘humour’, we’re now at a point where there has to be some meta element to the talking animal before it’s funny. As an example, an episode of We Bare Bears sees the optimistic adventurer Grizz leading the other two bears into the forest to survive like natural bears, with no mobile phones and no processed food. Over the course of this jaunt the bears devolve into angry, ferocious, actual bears. Until now, humans in the series have treated the bears as humans without batting an eyelid. Now suddenly they are terrified. By the end of the episode the wild bears have made it through a fast food drive-thru, have refuelled on burgers and shakes and are now behaving like teenage boy humans. The juxtaposition is now funny. They look like animals but don’t act like the real world animals they represent. The viewer holds both versions of ‘animal’ in mind.

Some carnivalesque stories can have a strong plot. Others put plot in the background.

- The Tiger Who Came To Tea is a great example of the carnivalesque. (The title gives away the plot.)

- Fortunately, The Milk by Neil Gaiman is a carnivalesque tale for slightly older readers, in which the father comes back from the corner shop with a tall tale. It’s no coincidence that the father tells the tall tale while the mother has been removed from the story. The tall tale is an historically masculine tradition. At its base, the tall tale is probably used to establish and maintain hierarchy — who is the best storyteller around this campfire, and who is taken in by my story? Boys are especially likely to use humour to establish and maintain hierarchy.

- Iconic New Zealand children’s author Margaret Mahy wrote madcap tales for middle grade readers, such as The Pirates’ Mixed-up Voyage.

- Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland is a sort of madcap adventure, though I feel the main interest comes from the wordplay. Alice In Wonderland has a meandering plot, much like Ulysses, and the earlier Wimpy Kid books (before Jeff Kinney started writing with movie script adaptations in mind).

- The Madeline books by Ludwig Bemelmans are carnivalesque. Madeline gets herself into some unlikely adventure where the reader has fun along with Madeline herself.

There are many, many examples of madcap humour in children’s literature. A lot of it involves slapstick, physical comedy:

- Falling down and breaking things

- Tripping/kicking/punching someone else by accident

- Landing in something disgusting (puddles, poo, mud)

- Landing on top of other creatures in pile-ups

- Falling over cliffs, down hills, into bodies of water

- Accidentally starting machinery, which springs into action and does something unexpected

- Provoking a wild creature by accident

- The list is endless

There is a trick writers often use to make madcap/slapstick/absurd behaviour even funnier:

Give funny characters an audience within the setting itself.

In the pilot of We Bare Bears, we are shown that the bears get around by two of the hopping onto the bottom bear’s back. “I’ll drive,” says the bottom bear. Next we see them on a commuter train, still on top of each other. The bears are largely ignored, because these creatures are accepted as part of the world of the story, but an old lady looks at them with interest. “Wassup?” says the top bear nonchalantly, and the scene ends. There is also something meta about this. The audience wonders, are these bears really a part of the setting, or are these strangers on the train the same audience as we are? The audience on the train exists not only for humorous purposes, but also to establish the ‘rules’ of the setting — humans accept these bears (so long as they behave like humans with a few animal quirks).

The audience effect is also used a lot for important monologues. I have noticed American audiences/writers really like to include an audience within a story. This must say something interesting about American culture, and is possibly related to the American Culture of Celebrity. A post for another time.

Perhaps in the category of Madcap Humour we can include any kind of surrealist/absurdist humour. Grandiosity, exaggeration, logical impossibilities, silliness, and comedy of chaos are other similar concepts. All of these increase any intensification/hyperbolic comedy.

10. META-HUMOUR

Jokes about jokes, or about the idea of comedy

Meta-humour is a subcategory of metafiction: What is metafiction, anyway?

- This Book Just Ate My Dog! This picture book by Richard Byrne combines irony (dogs eat books, not usually the other way around) and metafiction. The dog disappears into the gutter of the book. Readers are not normally meant to regard a book’s gutter as part of the reading experience.

- Press Here by Herve Tullet makes fun of digital books by turning an actual book into a fake book app.

- In Powerpuff Girls the main characters are often called ‘bug-eyed freaks’, ‘pumpkin heads’ and other insults which actually make accurate reference to the way they have been character designed — drawing attention to the fact that these are cartoon people.

- Wolves by Emily Gravett is another excellent picture book example.

- Dogman: Lord of the Fleas has a running gag about humour itself. What is it with you and POOP? Look, you can’t just tell the same joke… over and over… and expect it to still be funny! You can’t do the same things… again and again… and expect to get a laugh! Ya gotta avoid repetition…shun redundancy…eschew reiteration… resist recapitulation… and also, stop telling the same joke over and over! […] Why do you keep telling these stupid jokes? Because it’s distracting. Distracting from what? […] Ya just gotta switch expectations! The story itself includes many jokes about poop, repeated over and over. The story itself is metafictive, supposedly written by the two boys from Captain Underpants. This gag seems to poke fun at adults and teachers who would call this kind of humour facile.

There’s another type of joke which can probably fit in here: When the writer very specifically names something which would not be called that in the real-world, because it is far too on-the-nose.

- The Incorrigible Children Of Ashton Place gets a nanny from an institution called ‘the Swanburne Academy for Poor Bright Females’. This not only harks back to a time when things were more often called exactly what they were ‘orphanage, sugar diabetes’, ‘crippled’, but is a wink and a nod to the reader — this is what the place is called because it is fictional, and I, the writer, am giving you everything you need to know about this nanny up front.

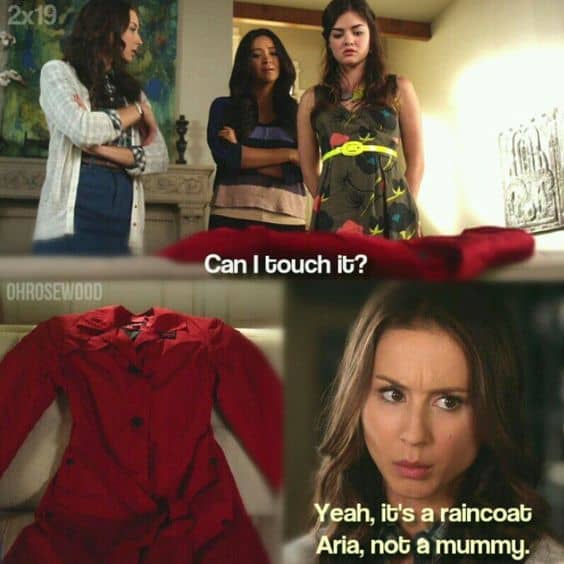

The following from Pretty Little Liars is slightly meta because the audience has been pulled into this supernatural world where anything is possible. Then, we’re reminded sarcastically that not everything in this supernatural world is necessarily magical and evil.

11. MISPLACED FOCUS

Attention is focused on the wrong thing

This category of humour is often a subcategory of irony. In picture books there is almost always some ironic distance between the text and the illustrations. This allows for dramatic irony, in which the reader knows something before the main characters do.

- The stand-out example of this joke, sustained throughout the course of the entire story is Guess Who’s Coming For Dinner? A hapless goose and pig think they’ve been invited to a wolf’s mansion to share a feast but they are in fact intended as dinner. These delicious dinner guests are so focused on gorging themselves that they miss the numerous clues (conveyed only in the pictures) that the reader is picking up. They avoid death only by pure chance.

- Wolf Comes To Town is funny because the people of the town don’t realise there’s a wolf among them, dressed as a human. Wolves are commonly this kind of trickster in children’s literature — this too comes from Aesop. Foxes are also cunning tricksters.

At a line level, this sort of joke can often be expressed as ‘metalepsis’. Metalepsis is a figure of speech in which a word or a phrase from an idiomatic expression is used in a new context.

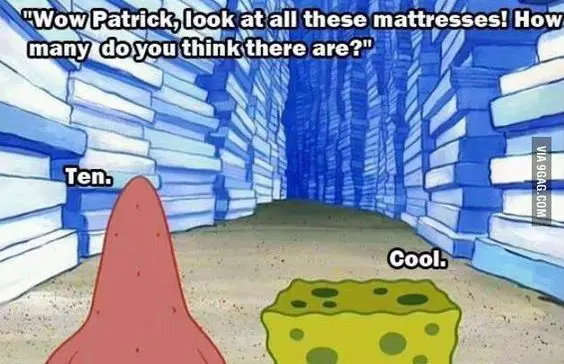

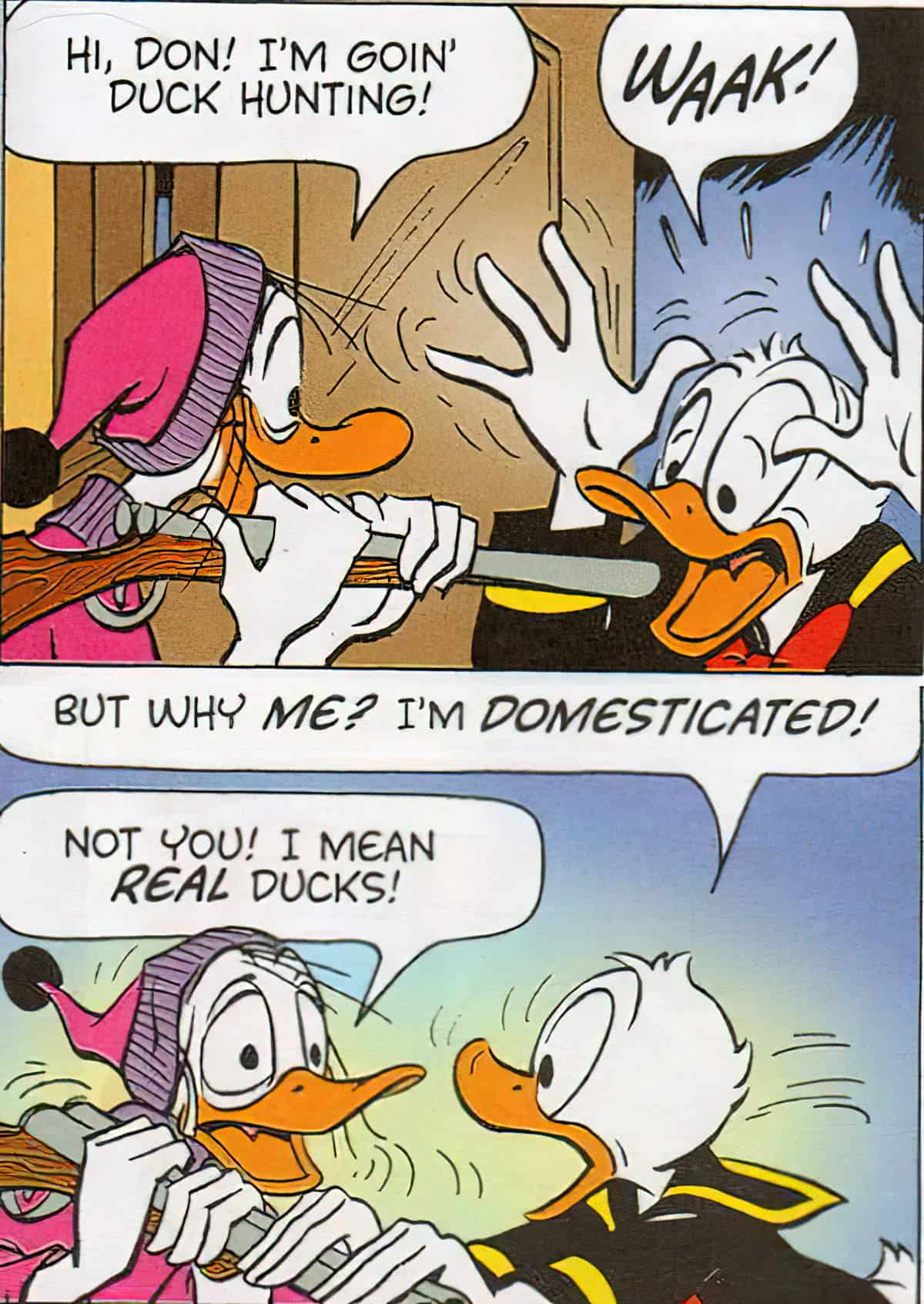

Related to metalepsis (or perhaps a subset of it?), a commonly understood concept or phrase is interpreted over-literally. This is why it’s so handy to have a stoopid character in the ensemble of a comedy cast. In Spongebob Squarepants it’s Patrick. In The Simpsons it’s Homer. In We Bare Bears it’s Grizz. In Seinfeld it’s Kramer. Seriously, there’s one in every comedy series. (As a side note, every stupid character needs a smart counterpart to bounce off.)

Avoiding mean-spiritedness, the stupid character also often comes up trumps precisely because of their stupids. For instance, their stupid remark will come across like a witty comeback. Or, the baddie will attempt to eat them, but because they’re stupid they end up escaping their fate entirely by accident. The stupid/naive trickster is beloved of young audiences.

- In The Seriously Extraordinary Diary Of Pig by Emer Stamp, our main character (Pig) is more naive than the reader. Commenting on his owners’ decision to grow ‘organik’ vegetables, he says, “Duck says the Sandals now grows a special kind of veggie what is called organik. He says this means they is super expensive so the Sandals gets lots more money when they sells them. Why would anyone wants money more than they wants veggies? Money doesn’t taste anywhere near as nice as veggies.”

- Later, when Duck says they’ve only just got back into the Sandals’ ‘good book’, Pig takes Duck literally, imagining an actual book with ‘Good Book’ as its title. Taking things literally is one common way of getting a laugh in children’s books and is, coincidentally, also the origin of most Dad jokes, in which the Dad deliberately misinterprets what has been said in order to raise ire.

CONCLUSION SO FAR?

When you’re a parent or a librarian or a teacher or a bookseller who reads a lot of children’s books, you sometimes wish for fun. Children’s books are often by their very nature “fun”. But there’s fun that’s strained and trying to appeal to everyone and then there’s fun that appears to be effortless. You read a book, are transported elsewhere, lose track of time, and never want the story to end.

Betsy Bird, from her review of The Incorrigible Children Of Ashton Place

- You can indeed shove almost everything into these 11 categories if you use your imagination.

- As Scott Dikkers says in his book expanding on this topic, jokes can be ‘layered’ by using more than one of these categories at a time. This is also very much true for the humour in children’s stories. The cleverest of the jokes fit three or four categories at once.

- As I suspected, irony is a common catch-all for anything that doesn’t fit the other categories. Irony blends with all and any of the others.

- Certain types of humour such as wordplay, madcap and hyperbole are very common in books for young readers.

- As children get older they are expected to recognise more subtle character humour, irony and eventually parodies. However, even the youngest of readers are able to pick when the picture says something different from the words. This in itself is a kind of ironic distance.

- Also, writers of children’s comedies don’t avoid, say, parody jokes just because the youngest members of the audience wouldn’t understand it, yet. They’ll most often include jokes for the older co-audience.

- Even if a children’s story isn’t comedy, almost all popular children’s fiction is funny in places. Even something like Pretty Little Liars, which might be mistaken for taking itself too seriously.

- Stories for and about girls are in general more earnest. The stars of funny stories are most often boys. (This is why Betsy Bird created the book Funny Girl — a collection of the moment’s funniest female writers.) While it’s perfectly possible to line your daughter’s bookshelves with funny stories for and about girls, the big-name most dominant funny stories in our culture are about boys.

- This is particularly noticeable in the cinema. Feisty princesses don’t need to improve the world in serious fashion a la Brave. There’s no reason, Pixar et al, why you can’t make a film starring a girl who is genuinely, consistently funny. Where are the stories starring girls in which humour is the main point? Frozen is a big name movie for/about girls but it is not all that funny. The funniest bits involve the male characters. The girls get a bit of slapstick. (NPR explained that Frozen is a bit different from most similar films in that the jokes are not all jammed into the start — the film does in fact become more funny as the film progresses. However, it’s interesting to note that the men on that podcast didn’t think it was sufficiently funny.) Inside Out, likewise, does not give preference to humour. Maybe this is the real reason why boys apparently don’t want to watch films starring girls? (So it’s said.) If you go to a popular TV show for and about girls (take Pretty Little Liars as an example again) you’ll find that the fandom does a great job of inserting their own humour by sharing memes with their own one-liners.

- Because The Onion is all about verbal humour — if we exclude the stock photography that accompanies the text — funny mainly because it looks so normal and serious — the categories above don’t do justice to the visual humour found in picture books, cartoon shows and illustrated books for children.

- The bestselling books for children contain humour aimed at adults (bookbuyers). David Walliams’ books are about 50/50 adult humour/kid jokes. Walliams is the contemporary Roald Dahl.

- Are Funny Books Taken As Seriously? In 2008 Michael Rosen set up the Roald Dahl Funny Prize to reward authors and books which otherwise get looked over in the major awards. Funny books are easier to read, garner a wider audience and by definition are not ‘serious’ books, so not ‘taken seriously’. They don’t challenge readers in the same way. This isn’t true, but is a common view. The body of scholarship on Pippi Longstocking (very light and funny) in Scandinavian is astonishing and shows that this story is taken seriously despite being funny. Pippi Longstocking is one of the few books that challenges authority. This is a rare example of a classic which, despite its status as a funny book, garners a lot of respect. So maybe things aren’t as bad as they look, and that after a book has acquired status as a classic makes people wonder what is being said about deeper issues. Wait a generation or two and funny books are then taken seriously.

EXTRA CATEGORIES SPECIFIC TO CHILDREN

12. VISUAL HUMOUR

What category is it when a polar bear crashes a child’s birthday party and ends up with jelly all over its fur, making it look like it just murdered one of the children? (From the pilot of We Bare Bears.) It’s not shock exactly, because it is funny rather than shocking — there’s no real taboo that’s being broken, and the reader knows the bear is harmless. Shared symbolism is important here. The audience interprets this humour with the understanding that red equals blood. This is visual humour.

13. EDUCATIONAL HUMOUR

People in children’s literature world like educational texts and that even applies to jokes. Educational value is not something adults look for when we seek our own comedy.

And like a lot of my favourite children’s fiction, [York] has jokes that are going to lead to kids looking up further information, just so that they can stay in the know. For example, at one point a kindly therapist asks why Tess draws crows over her heads when she sketches and her reply is, “That’s not a crown… That’s a nimbus of outrage.” My favourite, however, may be Theo’s shirt that says “Schrodinger’s cat is dead” on the front and then a zombie cat on the back with the line, “Schrodinger’s cat is ALIIIIIIVE.” I will be seeking this t-shirt out to buy presently. And for the record, I’m pretty sure there are a lot of references in this book I wasn’t getting.

from a review of York by Betsy Bird

14. KID LOGIC JOKES

Is there such a thing as kid logic jokes?

[Louis] Sachar builds kid-logic jokes into his stories—in 1989, he published a book of absurdist math problems called “Sideways Arithmetic from Wayside School,” in which, for example, a girl named Sue proves that her dog Fangs is a good dog by the equation “good” + “dog” = “fangs.” The letters correspond to numbers, and all the equations work—though I’ve yet to solve one.

The New Yorker

I don’t know about you, but I personally don’t find these funny. Kids do, which is why you’ll see the same old 1980s playground jokes still doing the rounds in 2017.

As [psychoanalyst] Martha Wolfenstein says, the joke that seems funny to a child may not seem funny to adults, or to children of different ages. The general rule seems to be that as you grow older the forbidden wish or emotion is gradually more disguised, and the joke that allows it expression becomes more complicated.

For examples, take the natural interest that children have in their own and other people’s bodies. Preschoolers will often spontaneously pulls their skirts up or their jeans down to show you their tummies, or lie on their backs waving their legs about and giggling. By the time they start school, this sort of activity has mostly been given up. Instead, children of six or so tease others by trying to pull down their pants; they now know they are not supposed to exposed themselves, so they try to expose someone else.

At about seven, actual physical assault is replaced by rhymes about exposure. There are literally dozens of those, most along the lines of

I see England

I see France

I see [Mary’s] underpants.To the adult such verses seem stupid and, if one has to hear them very often, annoying. But to the child, as Wolfenstein points out, they represent a giant step toward growing up. The conflict between id and superego, between the wish to see and show off nakedness and the knowledge that this is naughty and forbidden, has been sublimated into art. It is a very low form of art, but art nevertheless.

A year or two later, at about age eight, we begin to get verses about the nakedness of absent or fictional persons — another level of sophistication. Children this age recite rhymes like:

Hi-ho Silver everywhere

Tonto lost his underwhere.At nine or ten children get to the point where simply announcing the physical exposure of someone doesn’t feel right; there has to be an excuse for the event. So we get a new sort of rhyme. Here, for instance, is a taunt that uses the name of the victim’s mother:

[Mrs Smith] went to town

To buy a pair of britches,

When she came home she tried them on

And bang went all the stitches.Another charm of this one, no doubt, is that the person exposed is a parent, an authority figure. [It is also a fatphobic joke, still very common in 2017.]

By eleven or twelve most children have given up reciting such verses, but they still enjoy jokes and stories about physical exposure, especially if it happens as a result of an accident. Sometimes they will tell a story in which one of the characters is a younger child who doesn’t know something about the world that they have recently learned. Such a tale has a double payoff: it works, a psychologist might say, both in Freudian and in Adlerian terms (sexual release — superiority). For example:

Once there was a little girl walking home from school and she met a man on the street and he said to her, “Little girl, can you stand on your head?” So she said yes, and he said, “If you’ll stand on your head now, I’ll give you ten cents.” So she did, and he did. But when she got home she told her mother, and her mother was indignant. “You shouldn’t have done that,” her mother said. “All he wanted was to see your underpants.” Well, the next day when the little girl got home from school, her mother asked if she met the nasty man who wanted to see her underpants. So the little girl said, “Yes, and he gave me ten cents today, too. But I fooled him. I didn’t wear any.”

Alison Lurie: Don’t Tell The Grown-ups: The subversive power of children’s literature

RESOURCES FOR INVESTIGATING HUMOUR AND COMEDY

- A list of funny kids’ books suggested by M. Jerry Weiss

- For more on humour in children’s books listen to Episode 7 of the Kid You Not podcast.

- The Carnivalesque In Children’s Literature

- Playing with Words: Dav Pilkey’s Literary Success in Humorous Language by Evangeline E. Nwokah, Vanessa Hernandez, Erin Miller, and Ariana Garza

- Humor, a categorisation from Baughman’s Type and Motif Index of the Folktales of England and North America by Ernest Warren Baughman 1966.