You’ve probably noticed that ‘theme’ in everyday English means something different from how it’s used when talking about literature.

MAIN POINTS

- People mean different things when they talk about theme.

- When talking about literature, theme is a sentence, not a word.

- The theme sentence tells an emotional lesson…

- …which may be interpreted by some readers as a moral lesson.

- You’ll find expressions of theme in every single scene of a book/film.

HOW THEME IS USED IN EVERYDAY ENGLISH

“Well, the theme of today’s meeting was definitely muffins.” (Muffins dominated. Little else was discussed.)

A red themed room: Lots of red. Red cushions, red curtains, red rug… (Lots of red, repeating.)

There’s no question that a good theme can take a party from average to wildly creative, fun and jaw-dropping.

65 Of The Best Theme Party Ideas Actual Party Planners Could Think Of

In interior design, parties, weddings and so on, a theme is an overlay to a concept that helps tie all of the various spaces together. This isn’t so different from how we use ‘theme’ when talking about literature.

THE MEANING OF THEME IN LITERATURE

In fiction as in interior design, a theme is an overlay to a story that helps tie all the various parts together. Looking at it from the bottom up, all the various parts of a story work together to create that ‘overlay’ we call ‘theme’.

What do we mean by “parts of a story”?

- plot (Stuff happens. This is the ‘manifestation’ of the theme.)

- characterisation (Writers individuate characters by having them respond differently to moral dilemmas related to the theme.)

- imagery (metaphor, simile, motif etc. which doesn’t make complete sense until you’ve finished the story)

- setting (The wild west is a great setting to explore themes around hardship, community, American ideals and so on. Small hometowns near beaches are a great setting to explore themes around finding your true love, but really finding yourself.)

THEME IS A SENTENCE

These are real themes for real works, but I won’t tell you which works they refer to because they could actually refer to many:

- Love conquers all.

- There are no winners in war.

- When faced with collective hardship, communities come together.

- Humankind is headed for decay and ultimate destruction.

- Selfishness and greed lead to loneliness.

- Terror can change a person from civilized to savage.

Now let’s compare briefly with the ‘themes’ of my last five birthday parties:

- trains

- bananas

- bouncing

- balloon animals

- rainbows

Notice the difference in usage? Theme in literature is a full sentence. Not a word. Not even an abstract concept, but a complete sentence.

THE WORD ‘THEME’ HAS VARIOUS USES (EVEN IN LITERATURE)

That said, sometimes when people talk about theme, even in regards to literature, they will give you just the concept, without putting in a sentence:

- love

- war

- hardship

- destruction

This won’t help you understand the deeper meaning behind a work at all. I’m just acknowledging that this is how the word theme is frequently used in real situations.

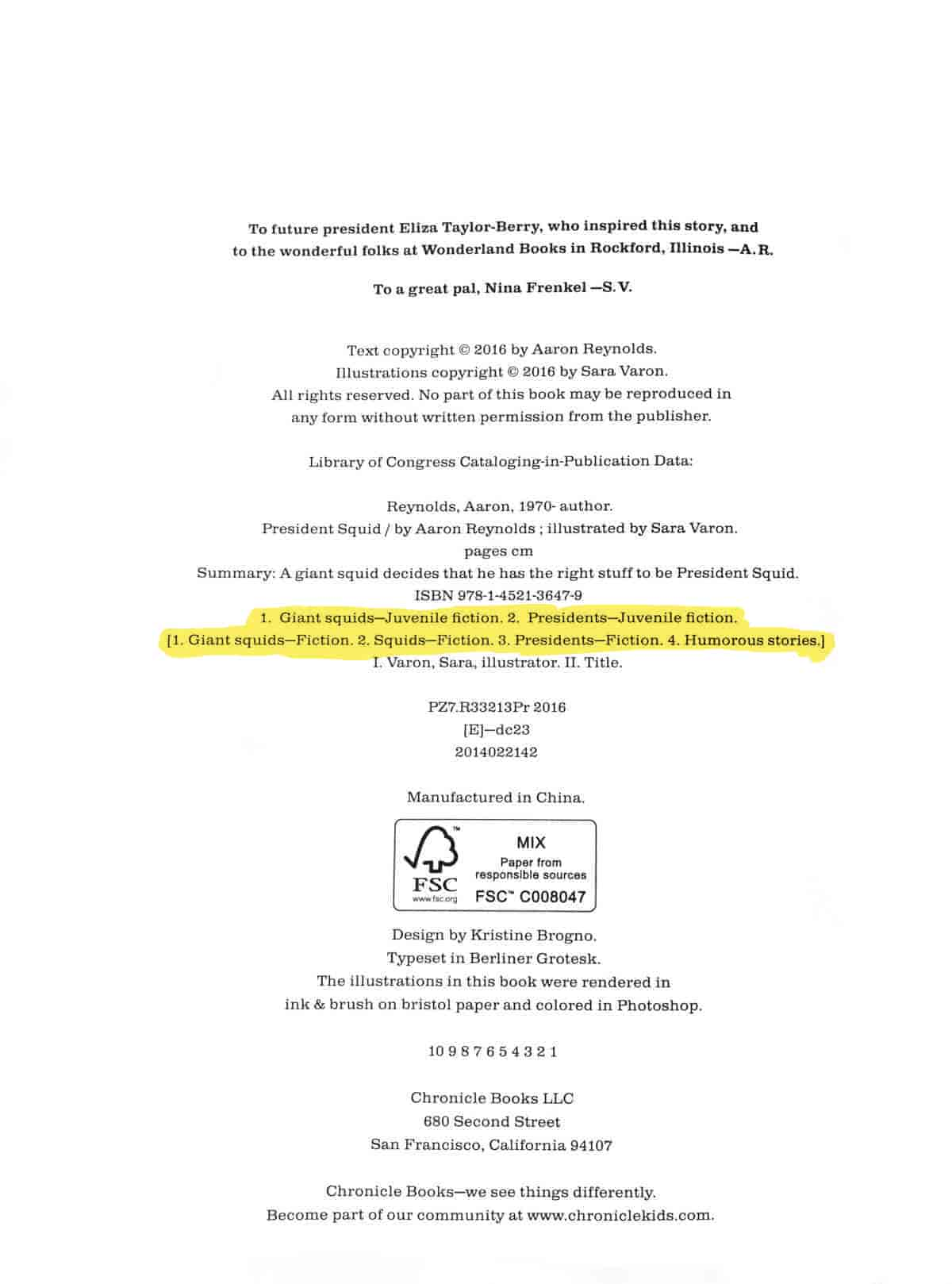

When people talk about ‘theme’ in relation to picture books they are sometimes talking about the tags used by librarians for cataloguing and ordering purposes: “family, friendship, loneliness” etc. You may find this list of words in the colophon. This information was developed by the Library of Congress to help librarians and others categorize and find books with similar (so-called “themes”) or content.

I mention the colophon as an example of what people frequently mean when they use the word ‘theme’ which is useful in one specific context (library cataloguing) and which is not at all useful if you’re doing a deep-dive into a work of literature.

In sum, people mean different things by ‘theme’ depending on what they’re doing at the time. This is why the concept of theme in literary analysis takes a little effort to get your head around.

THEME IS A SENTENCE, NOT A WORD.

Whenever you think about theme in literature, come up with a complete sentence.

Here’s why. Once you convey that concept in a sentence, this is evidence that you really understand what the work is about. Especially if you’re writing an essay, you’re far better off if you have the full sentence, not just the concept. The book is about ‘love’? Big whoop. That could mean lots of things. What is the work saying about love? This can only be expressed in a sentence.

The other benefit to writing a complete sentence: You avoid mistaking setting, genre and plot content for theme.

- WAR is not a theme. War is a setting.

- LOVE is not a theme, at least not on its own. Love might just be a genre (Romance, love story) or a subplot in a story with a theme concerning destruction.

- TEEN DRUG ABUSE is not a theme. Teen drug abuse is subject matter.

HOW WRITERS THINK ABOUT THEME

Good writers, if they think consciously about theme at all, think in complete sentences.

As a caveat, not all writers start with theme when they create a work. It’s very common to not know your theme until you’ve written the first draft (or drafts). This is the joy of writing. You understand the things that preoccupy you, deep down.

Many writers start with character. Some with setting. Stories can start anywhere, and in surprising ways:

It’s different for different people and different brains work differently. Some creative brains really like to start with the plot and go down into the inside and other people, like myself, I always start with theme first—what are we really talking about, what are we saying. So I tend to build from the inside out, but it’s actually very helpful in the room when you’re collaborating this way, that there’s other people in the room who are building from the outside in and can start throwing from that direction, creative ideas.

From interview with a Pixar writer

Whatever the process, writers collectively have a separate set of terms to describe what they do. Screenwriters have their own idiosyncratic terminology to describe this “guiding roadmap sentence which distils their story down to its most irreducible form”.

As Lisa Cron says in her book, Story Genius, “The skeptic in me thinks [the wide variety of terminology exists] partly so they can package their own brands… But in the end we should pick the version that makes sense to us.”

Robert McKee, for instance, uses the term ‘controlling idea’. Others say ‘theme line’.

Whatever writers call it, many come up with one or two sentences which serve as a constant reminder of both theme and road map as they create their work.

EXAMPLES OF THEME SENTENCES AS A WRITER MIGHT USE THEM

I have no idea how these writers really went about their process. By writing these, I come to understand something deeper about the stories as a reader. These longer sentences tend to have a theme sentence (or theme line) embedded within, or a theme sentence can be extricated:

- Detail a legendary journey while including the harsh realities of Wild-Western life to show that the ‘legends’ of the Wild West were ordinary men working in unglamorous conditions. (Lonesome Dove)

- Use a love story which starts with prejudice to illuminate how inter-class prejudice is rife and based on very little. (Pride and Prejudice)

- Show that manhood is independent of age by presenting a man-child in contrast to a child with emotional literacy beyond his years. (About a Boy)

- Show that it’s impossible to be joyful all the time by creating two side-by-side plots, with one thread taking place in a realistic modern day San Francisco, juxtaposed against another fantasy world inside one girl’s head. (Inside Out)

- A woman gets through her middle-aged disappointment with the world after the insulated life she has created for herself is invaded by exactly the same kind of horrible people she tries to keep at arm’s length. This will show that sometimes, no matter what you do, you can’t win. (I Don’t Feel At Home In This World Anymore)

- Show the falsity in 1960s American notion that everyone is free and devoid of all social restraints, that you can re-create yourself and become anyone you want. (Mad Men) > The American notion of freedom is ultimately false and costly.

- Utilising tropes from the female gothic tradition, show that a young woman’s most taboo qualities (menstruation) can unleash immense inner reserves, and that these unleashed powers can be the end of a girl, unless restrained. (Carrie)

- Show that you can’t hasten the onset of manhood by rejecting society completely by plonking a group of disaffected teenage boys in the wilderness attached to their home town/ This setting is ‘fake wilderness’, in the same way that the boys’ survival skills are fake and their aspirations unrealistic. (Kings of Summer)

- Depict the relationship between a boxing trainer and the demise of his poor, female protegee to show that when you truly love somebody, your actions speak louder than words. (Million Dollar Baby)

- Use the structure of a road trip to show the rapid coming-of-age of a married woman who — until now — has been under the thumb of her patriarchal husband. By ending in tragedy, this will show that emancipated, powerful femininity is dangerous to abusive men. But also, in this society, full unleashing of pent up wrath is dangerous to women themselves. (Thelma & Louise)

To understand a work of literature, let’s think like a writer. Remember: Theme is not a word. Theme is a sentence.

THEME IS IRREDUCIBLE AND PERVASIVE

The theme sentence is a coherent sentence that expresses a story’s irreducible meaning.

You know you’ve caught hold of a theme sentence when you can’t drill down any deeper. Whether you’re creating literature or analysing it, you know you really understand a work when you simply cannot drill down any deeper.

Every single scene of a work of literature connects to the theme sentence in some way. When you analyse a single scene of any work (your own or someone else’s), look for its expression in the characterisation, symbolism, imagery and setting.

Writers aim to sprinkle small details throughout the work which tie into the theme. Done right, these details will be subtle. They may also be ironic. (In a story with a pessimistic theme, the main symbolism may involve tropes from the romance genre, for instnace.)

Writers also aim to include at least one object which represents a bigger idea. This grows in meaning over time. (We call this kind of ‘meaningful repetition’ a motif.)

DISCOVER THE THEME RIGHT AFTER THE NEAR-DEATH SCENE

But you won’t notice this until you’ve reached the Anagnorisis part of the story (also called the ‘Self-revelation’, ‘Rebirth’ or something like that). You’ll find this part of the story after the some big battle or struggle in which the main character comes close to actual or spiritual death. At this point, the character will learn something they’ve been wanting to know. Unless it’s a tragedy, the character will also learn something about themselves which will help them going forward.

AND NOW FOR THE IMPORTANT PART: The audience will learn something about their life, and how to live meaningfully. This part of a story exemplifies the theme. (Even if the character learns nothing, because they are a dunce or whatever, the audience should get it.)

If you revisit a story again from the start you’ll see how every single scene leads towards that Anagnorisis/revelation/big theme scene.

THEME SENTENCE IS NOT NECESSARILY ORIGINAL

In fact, the theme sentence may sound trite and cheesy. With genre fiction especially, there are genre-determined themes along with genre-determined character archetypes, genre-determined settings and so on.

One overlooked thing that really sets the Lord of the Rings films apart from other franchises is how earnest they are. Most movies are so afraid of being “cheesy” that whenever they say something like “friendship is the most powerful force in the world” they quickly undercut it with a joke to show We Don’t Really Believe That! Even Disney films nowadays have the characters mock their own movie’s tropes (”if you start singing, I’m gonna throw up!”) It’s like winking at the camera: “See, audience? We know this is ridiculous! We’re in on the joke!”

But Lord of the Rings is just 12.5 hours of friendship and love being the most powerful forces in the world, played straight. Characters have conversations about how much their home and family and friends mean to them, how hope is eternal, how there is so much in the world that’s worth living for… and the film doesn’t apologize for that. There’s no winking at the audience about How Cheesy and Silly All This Is. It’s just. Completely in earnest.

And when Lord of the Rings does “lean on the fourth wall” to talk about storytelling within the film, it’s never to make jokes about How Ridiculous These Storytelling Tropes are (the way most films do) but instead to talk about how valuable these stories can be. Like Sam’s Speech at the end of the Two Towers: the greatest stories are ones that give you something to believe in, give you hope, that help you see there are things in a bleak violent world that are worth living for.

Earnestness is so much cooler than all the hip cynicism in the world. You go LOTR!

Lotrfansaredorcs on Tumblr

THE THEME SENTENCE TELLS SOME KIND OF EMOTIONAL LESSON

At this point you may be thinking, if a story contains an emotional ‘lesson’, aren’t we talking about moral now, as in ‘the moral of the story’?

Good question.

WHAT’S THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN THEME AND MORAL?

At its most basic, theme is The Message Of The Story. But a message isn’t telling you what to do or how to think. A message is just… neutral. On its own, a message is not a moral.

Here’s the thing:

Anyone who expects a moral or a message is sure to find one. That this is the case reveals the degree to which messages or themes are separate from the texts readers relate them to. In seeking messages, readers tend to confirm their own preconceived ideas and values: to take ideas from outside the text and assume that they are inside it. That prevents them from becoming conscious of ideas and values different from their own.

The Pleasures of Children’s Literature, Nodelman and Reimer

If a story has a moral, that is a partnership between story and reader. And it comes out of theme.

If the theme sentence of a story is, say, “Those who help others end up helping themselves,” the reader might justifiably conclude that the story contains a moral: “Help others.”

But another reader might think, “Rubbish. That’s not my experience of life. No one ever helps me when I need it.” That pessimistic reader might dig a hole in the yard and start hoarding canned beans, preparing for a solitary apocalypse. Two readers, exact same story, but this second guy empathised with the old man character who lived at the edge of the woods, and who was ostracised in the community survival effort.

In this way, the moral comes from the reader as much as from the story itself. Good writers mean for different readers to walk away with something different, or at least to consider different responses to a moral dilemma. Writers create each character to exemplify the various consequences of their different moral decisions when challenged by events in the story.

Some books, which no one tends to enjoy, were written by authors who started with a moral rather than a theme sentence. Go back just a century, children’s books existed for the purpose of teaching morals. (But those don’t find wide audiences any more.) Little Jimmy had his nose cut off because he refused to eat his peas, or some such.

You still get parodies of the didactic genre of yore. SpongeBob Squarepants frequently ends with a moral lesson at the end of the episode, sometimes shouted by an extradiegetic narrator. But this ‘lesson’ is always ironic, because the characters never learn a thing. Even as the didactic (moralistic) children’s books were in their heyday, there were always subversive authors publishing parodies cf. those gruesome tales about bad things that happen to children who don’t do what they’re told. (Turns out kids love stories about fabulously naughty children.)

SPEAKING OF PARTNERSHIP

Great works of literature have more than one theme. It all depends on who is reading, when, and what they bring to the table. There are as many versions of a story as there are readers. Theme cannot exist without reader collaboration, and readers must look beyond the What Happens (plot) to the metaphorical, allegorical, symbolic layer before accessing theme.

Here’s the great thing about literature, which frustrates some people who prefer the black and white/right or wrong mindset required in maths and physics: If you see a theme in a work of fiction which your professor and classmates do not, that’s EXCELLENT NEWS.

Now, go back and find all the small details which led you to that reading. This is your evidence.