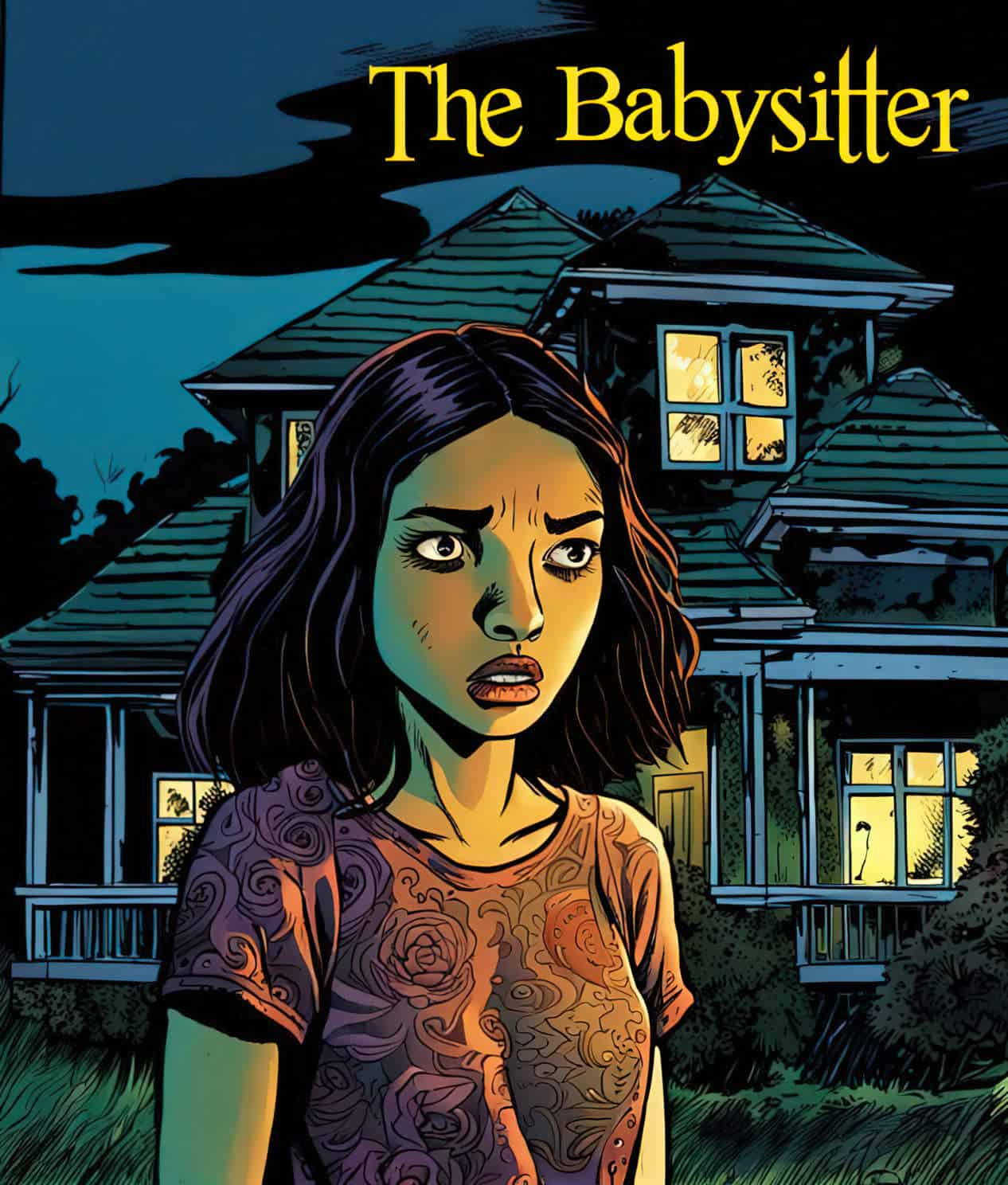

Moeroa didn’t really need a coat. She was only crossing the road. But a coat made it official: Tonight she would be paid for her work. She’d secured a real, official, proper, actual job.

She’d done jobs before, even babysitting. But only for her own brothers and sisters. As for money, Mum slipped her a dollar now and then for packing everyone’s lunchbox, right up to five bucks for cleaning chunder off the carpet. But a gold coin for sandwiches and a five-dollar note because Charleen was a sympathy-vomiter didn’t really count. Money from Charleen was called ‘pocket money’. But money from Cathy Ogden across the road would count as ‘pay’.

Cathy and Ray Ogden were grandparents, with full custody of their three granddaughters. Moeroa had caught snatches of complicated backstory. Trouble followed their middle son, in and out of jail. Drug related raruraru, she figured, and not just for personal use.

Moeroa didn’t even need to knock on the Ogdens’ door. Cathy had seen her coming and ushered Moeroa inside before the heat could escape.

“There’s kindling over there and logs. You know how to work a fire, don’t you, sweetheart? Just, don’t go burning the joint down, unless you get the girls out first, and then you have to burn the whole lot, including Ray’s junk out back so’s we can claim full insurance.” Cathy snorted to telegraph the joke.

Moeroa laughed politely.

“Go ahead and make a batch of biscuits while you’re here. I can’t guarantee the state of the oven so don’t look.”

“You look nice though, Cathy.”

“Oh, this old thing.” Cathy was dressed to the nines in her floral blouse and pressed slacks. She called ‘pants’ ‘slacks’. Moeroa was familiar with Cathy’s good blouse. Tonight she completed the effect with chunky jewels made out of Fimo or something.

“I like your new beads. Make them yourself?” Moeroa hung her own jacket on top of others near the door.

Ray appeared at the top of the stairwell and performed an arthritic twirl. “What about me? Don’t I scrub up?” Moeroa tensed up, thinking he might fall down the stairs. But he made it down in one piece.

As the most responsible babysitter in the whole of New Zealand, Moeroa listened carefully to the rest of Cathy’s instructions, and then the olds were backing out the wagon.

Now she was utterly alone — an odd feeling, especially with three noisy girls for company.

The girls competed to show Moeroa how fast they could do the jigsaw puzzles. “Them bits were always missing,” Mercedes explained.

Porsche built a jagged mess out of Legos and insisted it made a palace.

Harlee danced gravity-defying hip hop with four scraggly Barbies and one badass Ken. Someone had inked Ken up in sparkly gel pen tatts, all over his plastic arms and upper back. “He didn’t come with clothes except for stuck-on grundies, see?”

Moeroa didn’t feel like baking biscuits, but she thought maybe this was part of the job. So she located the cocoa-splattered Edmonds Cookbook on a dusty shelf full of instruction manuals and half-opened bills, got Mercedes to measure out the dry ingredients and allowed Porsche to push the microwave buttons to melt butter. The butter exploded so Moeroa located the Janola and cleaned the crusty microwave. It needed a wipe out anyway. No drama.

Harlee helped by sneezing into the mixture.

Still, you couldn’t detect contamination when the gingernuts came out of the oven. The Ogden house smelled of spices now. The three girls crunched on biscuits and hid under the duvet cover as she dressed in Ray’s oversized coat from the rack downstairs and read three, then five, then seven expired library books, then the first three chapters of a yellowing Roald Dahl paperback.

When Moeroa’s voice began to croak she noticed it was past eight o’clock. Bedtime. She eventually got their teeth brushed, pyjamas buttoned down, each girl tucked firmly into her own bed. She said a hard no to extra lullabies.

Moeroa had three little half-siblings of her own, so chaos didn’t ruffle her. But Mercedes, Porsche and Harlee Ogden were next level. They might have eaten too much sugar as well.

When their giggling subsided, Moeroa wiped a “toothpaste bomb” off the bathroom mirror, did the dishes downstairs, stoked the fire (which had almost died), considered eating one of the gingernuts, remembered the rank sneeze and decided not to. In a theatrical swan song she back-flopped onto the couch.

Moeroa had been acting a part. In this suburban play she starred as the mum of three girls, living in her very own house. Her place would be a bit tidier than this. Now the game had grown stale. In a single yawn she was gripped by the desire to mooch the thirty metres back home, to crawl into her own bottom bunk and nod off reading the book about talking cats. Damn. She should’ve brung it with her, except you’re not meant to read novels when you’re working, right? Now there was nothing to do but wait for the olds to come home. She yawned again at the ceiling.

That’s when the phone rang the first time.

The sound was alarming. Phones on the wall always screamed ‘emergency’. Moeroa had learned to associate their urgent call with her brother’s B-grade horror movies. Now she realised how a ‘bringg!’ could sound especially dire on a dark, cold night in a creaky-ass house like this.

Moeroa steadied her breathing then answered casually.

“Hello, Ogden residence.”

“Moeroa?”

“Oh hi, Cathy.”

Thank goodness it was only Cathy.

“Moeroa! Moeroa? Is that you, sweetheart?”

Cathy was yelling over top of some country and Western band. Music for background or not, she always yelled into phones though. “Did you get them three troublemakers tucked in tight?”

“Yeah, they’re asleep.”

“Any issues?”

“Nup.”

Moeroa decided not to launch into how Mercedes didn’t make it to the toilet. She’d mopped it all up, so no more needed to be said.

“We might be a wee bit late. I’ve already called your mum. She said that’s fine with her.”

“Okay.”

“We’ll be home around midnight.”

After Moeroa hung up she tried to deduce the time. This wasn’t easy because the microwave clock was an hour later than the wall clock.

So, 9:30 or 8:30. She hoped it was 9:30. Her own phone might tell her.

Before she could retrieve it, the Ogdens’ wall-phone rung out again.

Moeroa considered letting it go. It was probably Cathy a second time, telling Moeroa she might as well pull out the trundle bed because they’d be out line dancing the entire night. Then again, there could be an emergency.

“Hello, Ogden residence.”

Nothing. Not even the background clatter and clang of the Working Men’s Club.

“Hello?” she said again. “Cathy?”

“Have you checked on the children?”

Wasn’t Cathy.

“Ray?”

Ray was always pulling pranks. One time he got a hold of some lemons that looked like oranges and told Moeroa to bite one.

“Have you checked on the children?” the voice repeated.

Definitely wasn’t Ray. The voice was too young and Ray didn’t pull these kinds of tricks. He wouldn’t have seen this movie anyways. He only watched stuff about Vietnam and Hitler.

“Dat you Kahu, you stupid dick?”

The voice didn’t sound like her brother either, though. Kahu must have done something to disguise it. Maybe he downloaded one of them voice changer apps.

Click.

Left alone, holding Cathy’s phone, Moeroa half expected to hear the ominous build-up of horror music coming out of the walls. But she only heard breeze through the trees out back.

She’d already closed all the drapes. Still, she did another lap of the living room, readjusted the fall of the fabric. She got rid of peek-sized gaps.

Who else had seen that film about the babysitter? Everyone, probably. It was a remake, based on a well-known urban legend. If that stuff really happened it happened ages ago, somewhere in America, not in a small-to-medium sized town in the South Island of New Zealand.

She checked the street before overlapping the drapes. No black vans had pulled up outside, as if they would. But there was no reassuring rectangle of light from her own kitchen, either. Mum and Grahame must’ve gone to bed already, leaving her totally alone in the world.

Moeroa had absorbed the pop culture narrative that good babysitters frequently check on their charges, even if mums don’t hardly ever themselves, unless the kids are actually crying. So she climbed the stairs, bent to pick up a sock on the landing, then looked in on each of the three girls. Mercedes breathed heavily from her cupboard-sized nook. Porsche and Harlee slept in the bigger bedroom with a view over the Ogden Trash Pile, as Moeroa’s step-dad named it. Ray Ogden never finished what he started. Right now it was too dark to see his quarter-bricked BBQ area, or the spa bath he got from the tip with half the plumbing wrecked on it. Moeroa scoped out what she could under a clear, half-moon sky. Someone could easily hide down there, camouflaged by all that junk. She detected no movement, except for maybe a cat.

Four-year-old Harlee had shucked off her blankets. Moeroa tucked her back in.

The phone screamed out again.

This time she stifled a scream.

Okay. Fine. She wouldn’t have to talk into it. She’d only have to stop it ringing. The girls were stirring in their sleep. For a surprised, half-asleep moment, Porsche opened her eyes.

“It’s okay,” whispered Moeroa. “Someone’s pranking me.” Porsche seemed to get the point. She rolled over to face the wall.

Moeroa could not stand the urgency of the ringing. She padded down the stairs and knocked the thing from its cradle. The handset dangled on a rubbery strangulation of coiled cord. Donk, donk, donk, it knocked, like someone wedged into the wall cavity behind, trying to break through the plasterboard.

Breaking the lonely silence, Moeroa heard a voice.

“Did you check on the children?”

She grabbed at the handset and clutched it far from her face. “Straight up, what do you even want?”

“I want your blood, all over me.”

“I know it’s you, Kahu, or one of his dumbass mates. I’m telling Mum as well.”

“Charleen is dead.”

“Ha haaa. That movie accent is fake as.”

Click.

Moeroa left the receiver dangling. She knew it was her brother. It must be. She hadn’t told anyone else she’d even be here tonight, apart from her best friends Sef and Lili who didn’t go in for pranks. They were more into friendship bracelets. The three of them did clapping games at lunchtime and made their own lipstick out of cornstarch, hinu and crayons. It was Sefina’s birthday next week. After getting paid tonight, Moeroa planned to buy her some new Crayolas for the lipstick recipe, since they used all the pink and red ones up.

At least with that phone dangling, the bastards couldn’t ring back.

Moeroa sat at the bottom of the stairs. She pulled her cuffs down over her wrists and flexed her toes inside chunky socks. These were her favourite cosy socks. Normally they made her feel good, but their cosy-power wasn’t working right now.

Maybe she should put her shoes back on. She wasn’t sure how this was a plan. But she went to the front door anyway and slipped back into her canvas flats. Then she reached into her jacket pocket. The jacket looked bigger than it really was, hung on top of others in the entrance hall, like someone much bigger than her was meant to fill it. Like someone was hiding under the coats. Oh my life, someone could be hiding anywhere in this place. Junk in every corner.

Inside her pocket, the cold touch of cellphone offered instant comfort, but of course the battery had carked it. She’d inherited this crap one from her step-dad.

She didn’t know where to sit down, or how to sit down. She felt like Goldilocks, restless inside a cosy house that can never be truly cosy no matter what you do in it, because it isn’t really yours. She could sit in Ray’s comfy big rocker but it smelt like sweat and grass clippings. Cathy’s recliner didn’t rock, and didn’t stink, but over the years Cathy’s butt had hollowed out a nook that belonged to Cathy alone.

So Moeroa perched on the edge of the couch.

Moeroa hadn’t figured out the TV because Ray had some complicated set-up with five remotes plus rip-off Sky. The channels didn’t match the numbers and most aired static.

So her eyes kept returning to that wall of family photos. Some of the cheesy Ogden pictures had faded over time. One professional portrait had been taken back in the nineties. The whole Ogden family wore matching light-blue shirts. The boys wore their reddish brown hair in bowl cuts. More recent photos had been printed out on an inkjet printer, clearly running out of cyan. The middle son of these pictures looked nothing like the dark figure Moeroa had seen occasionally, announcing his comings and goings with a noisy Harlee. Whatever his name was, the Ogden Problem Child was a big, tatted up gangster these days, with a greasy tight bun. He probably wouldn’t want the likes of Moeroa sniggering at his 90s bowl cut. If he was here now he’d yank her by the neck, push her against the wall…

Then she had a worse thought. Maybe it was him calling on the phone. You never know, Cathy could’ve mentioned to her criminal son she was leaving his three precious girls with the thirteen-year-old kid from across the road. He could be ringing from the cells maybe, or what if he even busted out. He could be inside the house right now. For all Moeroa knew, he could’ve done a murder or three. Maybe drugs had nothing to do with anything. Cathy never said what he done to get himself locked up. She only said he was “a very silly boy” who got “mixed up with the wrong company”.

What if the Ogden son was the wrong company? Someone had to be The Wrong Company.

The thought sent a shiver right through her. She decided to go upstairs and stay there. She would get into bed with four-year-old Harlee, who didn’t take up much space on the mattress.

First, she turned on every single one of the downstairs lights. Prowlers don’t appreciate lights. If they turned back off, at least she’d hear the clicks.

Once again she ascended the stairs. This is how she always felt after watching Police Ten 7 on dark wintry nights. Jumpy. That’s probably why she was hearing things. Sounded like someone had got out of bed. They were rummaging around in the wardrobe. Damn, the phone must have woken one of the monkeys. Harlee better not be pulling junk out of that toy box again.

But Harlee was sound asleep. So was Porsche. So was Mercedes, even. The bedroom was real cold. Ghost-cold. Then she felt the breeze, coming in through the open window.

“Hell, no,” she muttered. That window had definitely been shut before. She glanced in fear at the wardrobe. It felt like someone was hiding in there. Couldn’t be, though. She’d seen inside of that wardrobe and it was chockas full of mess and crap.

She couldn’t hardly move from the spot. If she kept not breathing like this she’d probably keel over inside of a minute. Even her ears were ringing.

From under Harlee’s bed came a rustling noise of shifting junk.

Moeroa stifled a shriek. She darted out of the room.

The phone dangled right where she left it, no longer knocking against the wall.

With trembling fingers she dialled 111. It didn’t go through at first. She pressed the switchhook a few times, tried again.

“You have dialled 111 emergency. Your call is being connected.”

Come on, hurry! It never took this long in the movies.

Finally a connecting click. “Operator here, what service please?”

“There’s someone in the house!”

“111 emergency, do you require fire, ambulance or police?”

“I dunno! All of them!”

“Is anybody injured?”

“I don’t think so?” Moeroa’s whisper shouts barely escaped her throat. She hadn’t checked Harlee for vital signs.

“Connecting you to police now. Please stay on the line.”

A different voice, maybe.

“Where are you now, please?”

“Across the road at my neighbours’ house!”

A brief pause. The longest in Moeroa’s life.

“Are you calling from 31 Sylvo Str—”

“Yeah, and there’s someone upstairs, inside the house! I’m here on my own, babysitting. Please, can someone come quick? He might be an escaped convict, I think.”

“Does he have weapons?”

“I bet he does! Maybe!”

“A car is on its way. Please stay with me. What does he look like?”

“I haven’t actually seen him, but I can hear him. Big footsteps. I think there’s more than one!”

“You’re calling because you hear footsteps upstairs?”

“Yeah! Heavy man-sized ones! All thumpy and that. Oh my god—”

“And what else is happening?”

“Ain’t that enough, though!”

“And what’s your name?”

“Moeroa West.”

“How old are you, Moeroa?”

“Thirteen, tell them to hurry up!”

Damn, she should’ve said “thirty”. They might believe her if she said “thirty”.

“Actually, I’m thirty. I meant thirty.”

“Okaay. Is there a responsible adult in the house there with you, Moeroa?”

“I wouldn’t say ‘responsible!’ Would you call them ‘responsible’ who broke in upstairs through a window to kill people? Three little kids are up there too. Oh my god, oh my god, I think they might be murderers or kidnappers!”

“Any signs of a break in?”

“The window’s open and I heard a noise outside as well!”

“Hey, Moeroa.”

Oh hell no, that did not come out of the phone. It came from the top of the stairs.

Moeroa emitted a horror movie scream.

Another little voice receded back into the phone. Moeroa was in no mind to hear it.

Anyway, Kahu was laughing his head off. “Awww, I so wish I recorded that! She fully called the cops on us, bro!”

A second or two elapsed. She thought of all the insults under the sun. None made it out of her mouth.

“Sorry,” she said instead, quietly into the handset.

“Is this a genuine emergency?” said the tinny little voice.

Moeroa felt the heat rise in her face. Everything she’d said in the last two minutes sounded ridiculous now, even to herself. Her melodramatic script would surely come back to haunt her.

“Yeah. Sorry. It’s a prank. I’m so sorry.”

Whakamā.

Full of shame, she replaced the headset onto its cradle. She sat on the bottom stair, back to her brother, then curled into herself. She hugged her knees tight, hoping to shrink. “Oh my god, oh my god, oh my god.”

Kahu had spoken to someone behind him. Kahu’s dickhead mate Ashton Hurst, no surprise.

“Hey, Moeroa! You should make the cops come round still. That’d be crack up!”

“That scream, man.” Kahu lowered his voice but kept up with the sniggers. “She fully freaked out!”

Those two loose units swagger-hopped down the stairs. Kahu’s annoying skux friend slapped Moeroa on the forearm as he passed.

Moeroa wiped sneaky tears onto her sleeve and raised her face to the light. “Hoihoi! You gonna wake up the girls!”

“Aw, for shame. I didn’t know you were gonna call emergency, sis. We were waiting for you to stand by the bed so we could grab your ankles. Like on that crap movie we watched.”

“I really, really hate yous right now.”

“You said that movie wasn’t even scary though, eh. Did you change your mind now?”

“Not even. How did yous get in?”

“Parkoured up that pile a junk.” Ashton flexed his skinny guns. “Got in through a upstairs window. I’m hungers as. Do I smell biscuits? Yahtzee!”

“You aren’t stealing my biscuits. Those are mine, I made them.”

“Not steal. Jus borrow and never give back.”

After the boys left, Moeroa surveyed a dusty bookshelf, selected a Danielle Steele and fell asleep on the couch. Everything felt safe now. Humiliating, but safe.

Cathy and Ray Ogden arrived home at either 11:30 or 12:30.

She wasn’t even startled.

“Yoo hoo! Wakey wakey, Sleeping Beauty!”

Cathy was shaking her shoulder. Moeroa blinked hard, sat up and rubbed her eyes with the heel of one hand.

“Why are all these lights on, love? Electricity costs a bomb these days. You’ll know when you grow up and start paying bills. Doesn’t matter, Ray’ll walk you home. Don’t forget to take your bikkies.”

Cathy pushed the Tupperware at her.

It was only after flopping into her own bottom bunk that Moeroa understood she’d accepted crumbs as payment.

“Where’d this empty container come from?” her mother asked, next day after breakfast. But she already knew the answer. “You better take it back.”

“Cathy didn’t pay me for last night, by the way.” Moeroa hoped to gauge her mother’s reaction.

“Yeah, well.”

That was noncommittal.

“Cathy gets by on the smell of an oily rag. She deals with a lot, with all them grandkids and that troublemaker son. She doesn’t get to kick back in her retirement like most people. It was real nice of you though, e kō. I know she appreciates it, even if she doesn’t exactly say it in words.”

Moeroa didn’t take the Tupperware back. She went outside with it, thought about crossing the road, then chucked it into the recycling bin.

Two weeks later, Cathy came over for a cup of coffee and a smoke with Charleen and hadn’t forgotten about the Tupperware.

“Where is it, e kō? Didn’t you take it straight back over like I told you?”

Moeroa shrugged and acted dumb.

“What’s got into you?” Charleen turned to Cathy. “This one’s vacant lately. Growing pains. Mainly painful for mama, though.”

“Where’s my damn money?” Moeroa thought, but didn’t say.

“Speaking of growing, where’s that hulk of a son? Ray wants Kahu’s help to clean up the yard. Finally! Reckons he’ll build me my vege garden after all these years, in time for my big six-oh.”

“I hope he takes you out as well, Cath. It’s a milestone birthday.”

“I’m working on that.”

Moeroa felt a bit stink.

She felt a bit stink until Kahu came home waving a twenty dollar note. Ray gave it to him for a single morning’s work.

“How come you got paid, fucker?”

“Let’s have a peaceful dinner,” said Grahame. “Kahu worked hard today, shifting all that junk. Looks great over there. My eyes feel relieved for the first time in years.”

“I also did the whipper snipping and mowed the front lawn,” Kahu added. “Heavy work.”

“Babysitting ain’t exactly a walk in the park.”

“Boosh. Got any brains you just shove them into bed and watch the TV.”

“There’s a bit more to it than that, son.”

At least their mum was backing her up.

“Take a lesson from your big brother,” advised Grahame, reaching for the sliced beetroot. “Babysitting, gardening work, stuff like that is a bartering economy. Want to get paid the going rate? Name your price up front.”

Moeroa looked at Kahu. “Did you name your price up front, bro?”

“I was there the entire morning, as a favour. Twenty bucks still don’t make minimum wage. Ray must’ve thought I deserved some compensation though. Cos I did a excellent job.”

“Did you use Grahame’s whipper snipper, though?”

Grahame raised his eyebrows.

Moeroa had witnessed Kahu taking it out of the garage. He walked across the road with Grahame’s petrol can, whipper snipper and a spare spool of cord as well. Not to mention a whole lot of snacks from the pantry. And an entire thing of milk.

Moeroa swallowed a mouthful of dry hamburger bun. “Speaking of ‘economy’, aren’t you gonna reimburse Grahame for the use of his tools, bro?”

“Don’t start down that track,” Grahame cautioned. “I’ve always treated you kids as my own. If I made a fuss every time you wasted my stuff I’d send myself into an early grave.”

Moeroa wasn’t hungry. She didn’t excuse herself.

“What’s got into her?” she heard as she padded down the hallway.

A week after that, Moeroa walked Cathy’s girls as well as her own little brothers and sister home from school, opened her own front door and smelt Cathy’s menthols. She wondered if Cathy was here again to talk about Tupperware. So she quietly busied herself in the kitchen, preparing the kids their snack.

Charleen called from out back.

“Moeroa West, is that you? Haere mai!”

“I’m just getting the kids their cheese and crackers.”

“Come here now. I’m not gonna hit you but I will chase you down.”

Maybe her mum’d found the Tupperware. The bin man would’ve come this morning. Her mother might’ve opened the lid and seen it sitting there, right on top.

But when Moeroa joined her mother and Cathy on the patio, it wasn’t Tupperware sitting centerstage on the crate between them. It was a bit of paper. Looked official.

Cathy regarded Moeroa suspiciously and took a long drag on her smoke.

“What’s all this?” Her mother passed Moeroa the sheet of paper. It was a phone bill. “Someone made a 111 call from Cathy’s.”

Naturally, Moeroa hadn’t mentioned any of that. She’d felt kind of stupid for failing to recognise Ashton’s disguised voice. She felt even more stupid for screaming. She felt stupidest of all for calling emergency services, which might’ve stopped someone in a real emergency from getting urgent help. That last part didn’t bear thinking about. So she hadn’t thought about it, on purpose.

“Were you messing about for fun?” Cathy asked. “Because they charge for non emergencies, you know. They want six dollars for that.”

Charleen’s face wasn’t as angry as her voice. She rubbed Moeroa’s lower back. “Hei aha. Just tell us what gave you a scare.”

Moeroa disappointed herself by bursting into tears. “It was Kahu and Ashton. They got in the house and pranked me half to death.”

Then she was required to tell the entire story, twice, because Cathy couldn’t follow.

Charleen shook her head like she was disappointed in her eldest son. But still it was Moeroa who had done something wrong. “If you got scared for any reason, why didn’t you call me? I was right across the road, for back up. Like we said.”

Moeroa kept crying, trying to stifle it.

“For crying out loud,” Cathy said eventually. “What a hoo ha over nothing. Well, boys will be boys.” She took a slurp of coffee. Then her brow furrowed again. “Moeroa, didn’t you lock up the house all safe and sound like I told you? How did them two troublemakers get in through a window? Did you leave it open in the middle of winter? I had the fire stoked up and everything.”

But Moeroa was crying angry tears now, and had her face pressed into her mother’s collar bone.

“Aw, no need to get upset,” Cathy said in a softer voice. “Six bucks won’t break the bank. You can make it up to me next week. It’s school holidays, right? Ray’s turned around and said he’ll take me out to the Casino for my birthday lunch. I’ll be needing a responsible girl like you to keep an eye on the monkeys. They had so much fun with you last time, sweetheart. They won’t stop talking about their new best friend.”

Moeroa lifted her face from her mother’s soft neck. In the pause, Moeroa hoped her mother would say something to Cathy about money for babysitting, not just money for non-emergency calls that weren’t even her fault. But she didn’t.

Moeroa wiped her cheeks with her sleeve. Mascara darkened her cuff. “I’ll think about it.”

“Good, well I’ll let you know what day. Tuesday’s cheap day for seniors. So I guess we going on the Tuesday with all the proper old-olds.”

“If Ray can afford to take you out to the Casino, he can pay the babysitter as well, though.”

When Cathy shot her a surprised look, Moeroa realised she’d said that out loud.

“Girrrl,” her mother cautioned.

Cathy leaned forward in the fold-up chair, picked up her cigarettes and tapped another from the box. She didn’t light up but it dangled on her lips, stuck there for now with gluey saliva.

“Drives a hard bargain, your baby girl.”

“Twenty bucks for half a day,” Moeroa added quietly. “Or a evening. That’s still mates’ rates.”

“Twenty bucks? Oh, I see where it’s come from now.” Cathy did light her cigarette. “Here’s the thing, sweetheart. We women have always been expected to do childcare. It’s not what we do, you see. It’s who we are.”

“And that’s fine with you?”

“If I don’t look after those poor wee girls who else is going to do it? It wasn’t me who abandoned them kiddies, but I love them and I do what’s right, every single day. Life’s not fair, young lady. You’ll find that out soon enough.” Cathy nodded conspiratorially at her mother. “Charleen knows what I mean.”

Moeroa had simmered long and hard on this very point. Her argument was fit to burst. “What’s more important to you, though? The yard or your grandkids?”

“Don’t talk rubbish. Anyway, I paid you in biscuits.”

“I can’t buy stuff with biscuits, though. And everyone else eats them.”

“That was heavy work your brother done. I doubt you could manage it, a scrawny wee thing like you. I know I can’t. Even Ray’s getting past it himself.”

“Would you trust Kahu or any of his mates to babysit your grand-daughters, though?”

“See, girls mature faster—”

“Because him and his mate Ashton thought it was a laugh to climb up on Ray’s wobbling trash heap, snap off part of your trellis, jimmy open a window and scare the babysitter for fun. If you’re gonna pay my brother for his manly muscles, you better cough up for my girly maturity.”

Cathy said nothing for a while. Then finally she did.

“I wish I was rich, Moeroa. But you know we can’t afford to pay a babysitter as well as a nice day out for my birthday.”

Cathy left peaceably enough, but Moeroa knew to expect a lecture from her mum.

There was no lecture. Just, “Auē! You are turning into one strong wāhine.”

Moeroa felt relieved but also guilty. She might’ve ruined Cathy’s entire sixtieth. She mooched off to her room.

But she returned to the outside table with A4 paper and marker pens. She needed to sit next to her mother, to be sure there were no negative vibes. She set about making her poster for the petrol station pin board.

Local babysitting service.

Reliable, responsible, $15/hr.

Reference available upon request.

She hesitated before writing more.

“Do you reckon Cathy’ll recommend me though, Mum? Should I put that bit about the reference?”

“She’ll probably say you’re reliable, responsible and don’t come cheap.”

Moeroa grinned. That was actually perfect.