-

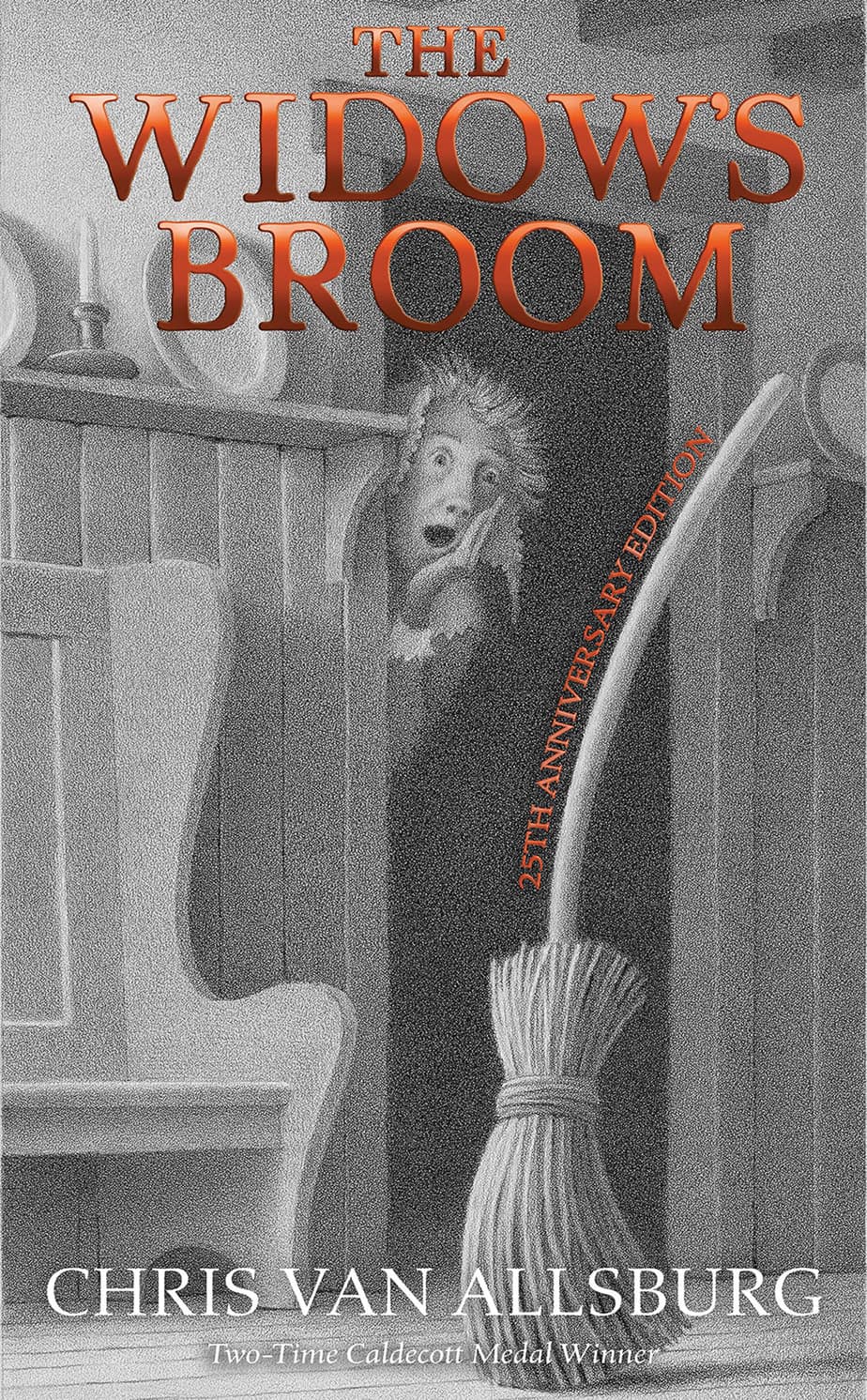

The Widow’s Broom by Chris Van Allsburg Picturebook Analysis

“The Widow’s Broom” is a 1992 picture book by American author illustrator Chris Van Allsburg. Like many of Van Allsburg’s books, this one remains popular with teachers, partly because this is a storyteller who requires the reader to do a little work. Students can practise their inference skills in class. Like all good stories which […]

-

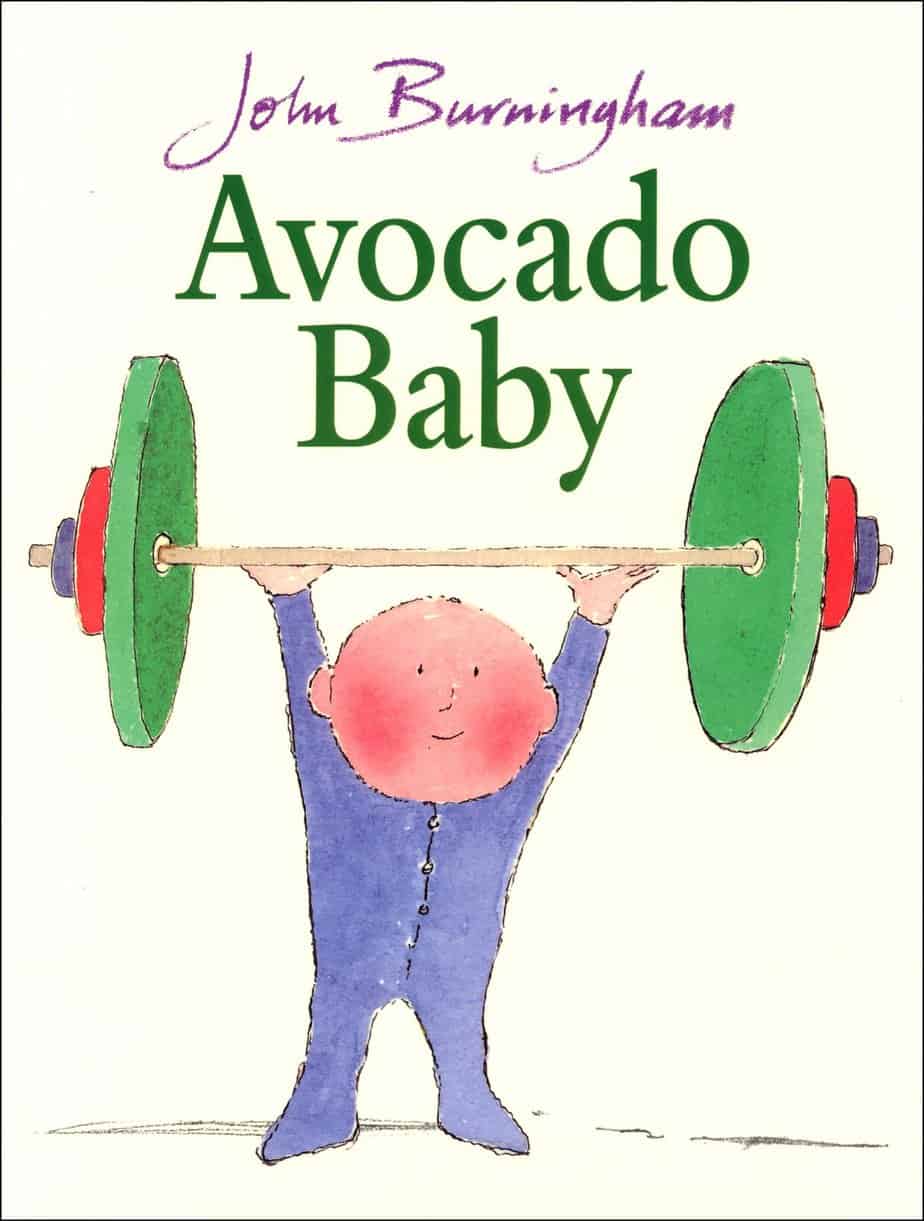

Avocado Baby by John Burningham (1982) Analysis

Avocado Baby (1982) is a picture book written and illustrated by John Burningham. This was my first introduction to John Burningham. Our teacher read it in class. I was about six.

-

Magic Words and Spells

In children’s fantasy, enchanted realism and magical realism, there is often an arc word (leitwort) which enters popular lexicon, or sticks in the mind long after the reader leaves the story. These magic words sometimes become a part of the child’s own imaginative play, an improvised version of early childhood fan fiction. Where Do Magic […]

-

Fairy Cup Legends In Modern Children’s Stories

Is fairy land real? Some children’s stories would like us to think so. Their endings contain a ‘wink’, encouraging readers to carry the possibility of fantasy lands with them, even after the story draws to a close. This is one way of achieving resonance. We might argue this is a cheap trick. Enter Richard Dawkins, […]

-

Snow White and Rose Red Fairytale Analysis

There are many slightly-altered versions of “Snow White and Rose Red” but I’ll refer to a version set down by the Grimm Brothers. This is the story of a lesser known Snow White.

-

The Pied Piper of Hamelin: Legend Or Fairytale? Analysis

The Pied Piper is not technically a fairytale. It is at least part legend. Hamelin was a real place, and it is believed that once, in this German town, all of the children really did disappear in a short space of time.

-

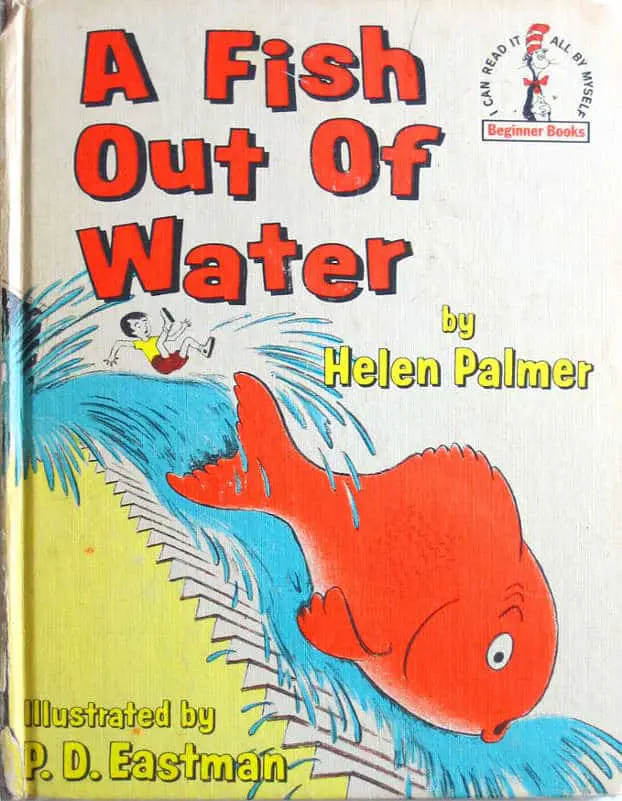

A Fish Out Of Water by Helen Palmer Analysis

The story of Helen Palmer is — from the outside, certainly — a sad one. Helen is ‘the woman behind the man’ in the Dr Seuss duo. It was Helen who encouraged her husband Theo to start writing picture books. When the marriage ended and Theo embarked upon a second relationship, Helen suicided. It would […]

-

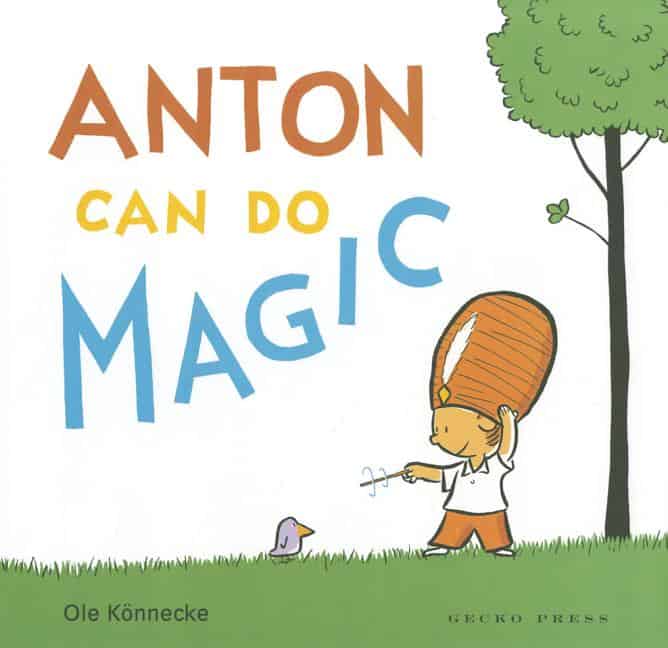

Anton Can Do Magic by Ole Könnecke Analysis

Anton Can Do Magic by Ole Könnecke is a great book for parents who would like to teach their kids The Magic of Reality (as expressed by Richard Dawkins and others). Written and illustrated by a German picturebook maker, this was translated by New Zealand’s Gecko Press. Anton Can Do Magic is part of a […]

-

The Magic Porridge Pot And Famine

The Magic Porridge Pot is also known as Sweet Porridge and goes by various similar titles. This is a fairytale borne of famine.

-

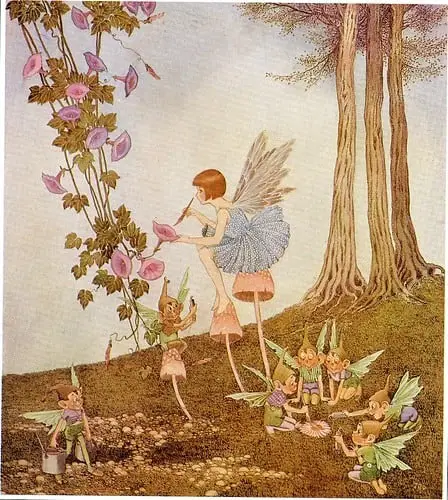

Mushrooms In Children’s Illustration

This one goes out to all those mushroom lovers out there.