Birds are much older than we are — living dinosaurs. Across cultures, birds function as smart collaborators with humans. We now know how smart (some) birds really are, but we have long had a sense of their canniness. The smartest bird in the world is currently thought to be the New Zealand Kea, which isn’t so great if you live in New Zealand and the kea is chewing the bits of rubber off your car.

New Zealand’s kakapo is also a bit of a… character.

BIRDS AND THE ANCIENT GREEKS

Birds are frequently utilised in tales of transmogrification. Wings are frequently stuck onto chimerae. This surely has something to do with humans’ long-held wish-fulfilment fantasy of being able to fly.

Take the Ancient Greek mythological siren.

Bird symbolism in the Greek imagination was common. Reverse-engineering the meaning of all these story-birds isn’t easy. For instance, we’ll never know for sure why Sirens took the form of a hybrid bird-woman, but we do know that in ancient mythology birds represented a number of things:

- oracles

- enchantresses

- messengers of deities

- mediators (between the human world and the supernatural realm)

Over the centuries, however, the Siren transformed. In the Middle Ages, the spread of Christianity throughout Europe saw the Siren morph from a bird-woman into a fish-bodied being, who personified the dangers of both the sea and female sexuality. The seventh-century medieval bestiary Liber monstruorum diversis generibus, or the “Book of Monsters,” is one of the earliest examples of this transition, describing Sirens as sea-girls who “are like human beings from the head to the navel, with the body of a maiden, but have scaly fish tails, with which they always lurk in the sea.” Illustrations from the period clearly reveal the difference; the Sirens now have voluptuous bodies, perform erotic moves, and exhibit brazen tactics of seduction, such as staring longingly into mirrors and combing their hair. These Sirens no longer symbolized the spirit, but rather, the pleasures of the flesh.

Vice

BIRDS IN HINDUISM

According to Hinduism, birds represent higher states of being.

Two birds, inseparable companions, inhabit the same tree; the first eats of the fruit of the tree, the second regards it but does not eat. The first bird is Jivâtmâ, and the second is Atmâ or pure knowledge, free and unconditioned; and when they are joined inseparably, then the one is indistinguishable from the other except in an illusory sense.

The Upanishads

There is also a famous Hindu tale about an ogre. (Ogres are found in pretty much every culture.) The ogre tells his daughter where he keeps his soul: “Sixteen miles away… is a tree. Round the tree are tigers, and bears, and scorpions, and snakes; on the top of the tree is a very great fat snake; on his head is a little cage; in the cage is a bird; and my soul is in that bird.”

We know from cave paintings that the bird had come to symbolize the soul (and also trance-like states) by the late Paleolithic era.

BIRDS AND THE EGYPTIANS

If Hindus believed the bird was a representation of the human soul, the Egyptians went more literal with it: They gave birds human heads. (“Androcephalous” birds.) The concept of the Egyptian soul is pretty complex. If we look only at the Ba part of the soul, this is supposed to fly away from the body after death.

Birds with heads are also found in art done by the Ancient Greeks and Romans.

BIRDS AND ISLAM

The pagan Arabs were especially steeped in superstitions related to birds. They believed seeing certain birds at certain times were good omens and seeing them at other times were bad omens.

“Do they not see the birds held (flying) in the midst of the sky? None holds them but Allah (none gave them the ability to fly but Allah). Verily, in this are clear Ayaat (proofs and signs) for people who believe (in the Oneness of Allah)” (16:79)

The Quran

Allah is in command of the birds as well as all of Creation. Allah decides where birds fly or roost. The flight of birds is not dependant upon where good luck or bad luck resides.

BIRDS IN THE OLD TESTAMENT

The Old Testament is all about ‘clean’ birds versus ‘dirty’ ones. So don’t be thinking that birds connected to the human soul is necessarily a good thing.

And he cried mightily with a strong voice, saying, Babylon the great is fallen, is fallen, and is become the habitation of devils, and the hold of every foul spirit, and a cage of every unclean and hateful bird.

Revelation 18:2

When Noah gets off the ark he thanks God for the clean birds he took onto the ark with him. What’s the difference between a clean bird and a dirty bird? (Okay, ‘unclean’.) Dirty birds eat carrion. The clean birds mostly have a diet of grain, fruits, and vegetation. Humans are safer when eating ‘clean’ birds than birds who eat dead meat themselves — less chance of getting sick. However, when all the birds of the Old Testament are taken as a group, there is no clear-cut line we can draw between a clean and an unclean one. To our modern taxonomies, some of the birds on the unclean list seem a bit random.

BIRDS AND JOURNEYS

In storytelling, when birds set off on a journey, the viewpoint character is often also setting out on a journey. (But when the camera pans to the sky near the end of a story, this may mean that someone has died.)

GIANT BIRDS

Giant birds symbolise a creative deity.

- Hindus of Vedic times: the sun was depicted in the form of a giant bird (eagle or swan)

- Germanic tradition: depicted some kind of solar bird, also gigantic

BIRDS AND STORMS

According to Scandinavian mythology, a gigantic bird called Hraesvelg (or Hraesveglur) was thought to create wind by flapping its massive wings.

In North America, the supreme Being is often equated with the mythic personification of lightning and thunder as a great bird.

BIRDS AND FAIRYTALE

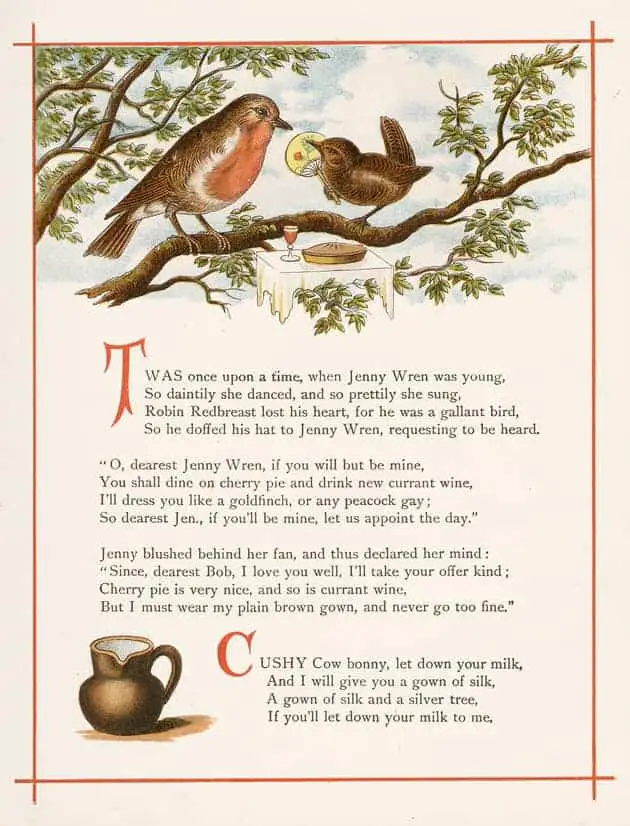

In fairytales, many birds can talk as well as sing. They tend to stand for amorous yearning, alongside arrows and breezes, funnily enough.

Birds are sometimes thought to be metamorphoses of someone’s lover.

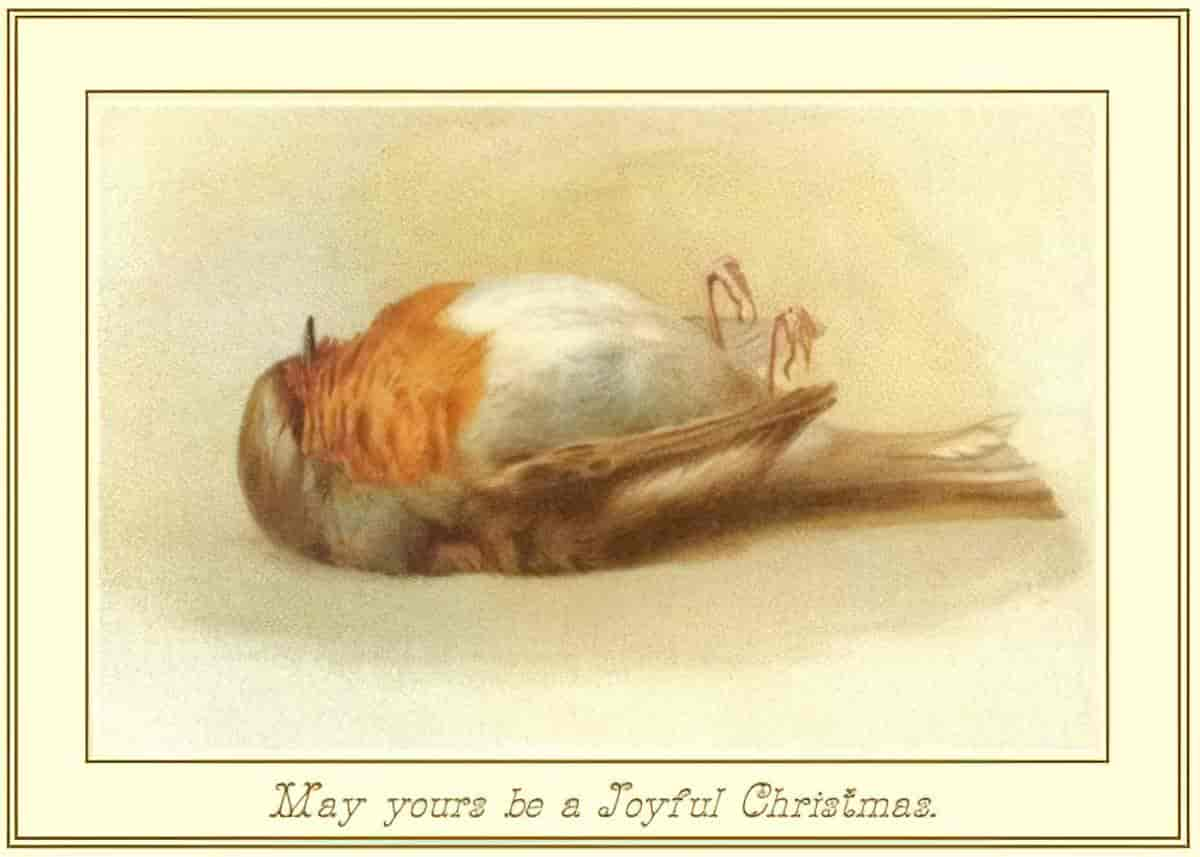

How miserable it must be to be born a little bird! I am thankful that none of my children will ever be birds, for they can do nothing but cry, ‘Tweet, tweet,’ and always die of hunger in the winter.”

“Yes, you may well say that, as a clever man!” exclaimed the field-mouse, “What is the use of his twittering, for when winter comes he must either starve or be frozen to death. Still birds are very high bred.”

Tiny said nothing; but when the two others had turned their backs on the bird, she stooped down and stroked aside the soft feathers which covered the head, and kissed the closed eyelids. “Perhaps this was the one who sang to me so sweetly in the summer,” she said; “and how much pleasure it gave me, you dear, pretty bird.”

Thumbelina by Hans Christian Andersen

BIRDS AS MESSENGERS

In a number of stories about the creation of the earth (demiurgical stories) birds come from the great bird-demiurges of the primitives. These are the bearers of celestial messages (and also creators of the underworld).

This is why birds are thought to be messengers. See also the dove in the story of Noah’s ark.

BIRDS AND COLOUR

Birds inherit secondary symbolism depending on the colour of their plumage. For example:

BIRDS AND DEATH

It’s logical that we associate birds with death itself. If you sit still enough outside birds won’t notice you’re there and will walk happily around you pecking at the ground, until you move a muscle and they all scatter away.

A novel-in-verse about loss… and what happens afterwards

Twelve-year-old Birdie Briggs loves birds. They bring her comfort when she thinks about her dad, a firefighter who was killed in the line of duty. Life without her dad isn’t easy, but at least Birdie still has Mom and Maymee, and her friends Nina and Martin.

But then Maymee gets a boyfriend, Nina and Martin start dating, and Birdie’s mom starts seeing a police officer. And suddenly not even her beloved birds can lift Birdie’s spirits. Her world is changing, and Birdie wishes things would go back to how they were before. But maybe change, painful as it is, can be beautiful too.

The ultimate stillness is death. Birds will naturally reclaim the space.

Certain species of birds are more connected to death than others. Brightly coloured birds, not so much. The blacker the bird, the more we connect it to death. Birds who eat carrion and who are also black are most linked to death.

BIRDS AS HUMAN SPIRIT

Every winged being is symbolic of spiritualisation. The bird, according to Jung, is a beneficent animal representing spirits or angels, supernatural aid, thoughts and flights of fancy.

A Dictionary of Symbols by J.E. Circlot

Since birds fly through the air, it follows that birds symbolise the human spirit. Birds occupy the Heavens — a space many hope to inhabit after leaving this earth. In children’s literature (so-called) the robin of The Secret Garden by Frances Hodgson Burnett is coded as the spirit of Colin’s dead mother, and she leads the children into the secret garden so that they can experience a spiritual awakening (or character arc).

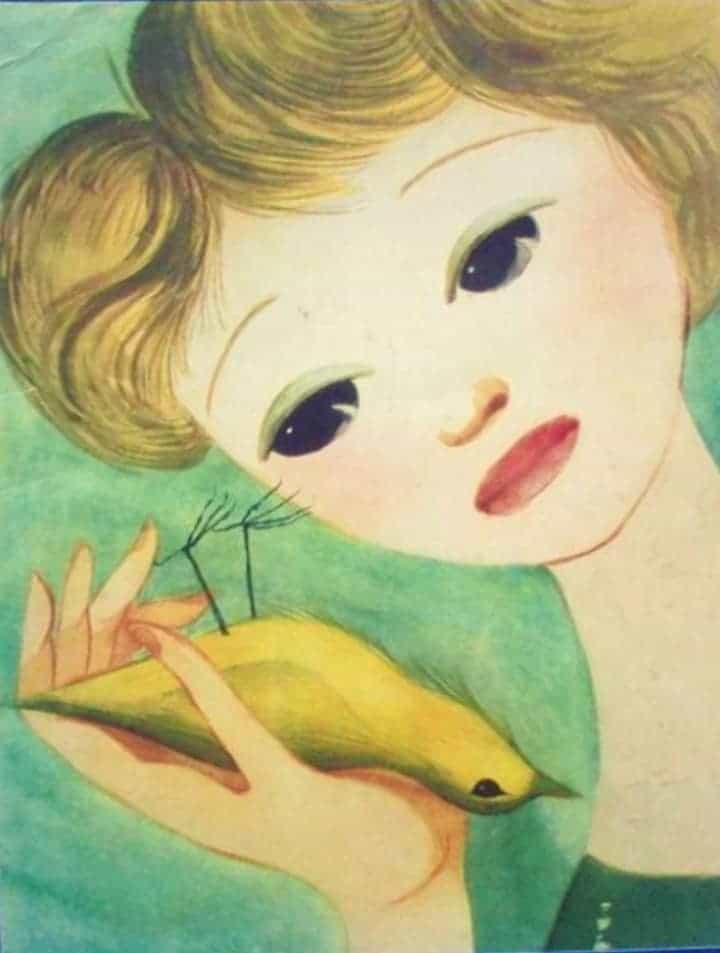

THE FIRST SORROW BY IDA RENTOUL OUTHWAITE

When Dicky died, the great big night

Came down and covered all the light.I climbed the hill to find a star

Where all the gold-eyed daisies are.I could not find the littlest spark–

The stars were hid behind the dark.The daisies shut their eyelids white,

And there was nothing but the night.My singing bird, my sweet, my own!

Why did you leave me all alone?You loved to sing away the hours,

And fluff your wings like yellow flowers.I gave you dwe, and berries red,

And shining seeds, and mossy bed.But somewhere else you longed to be,

And you loved someone more than me.I wonder if the Fairies heard

And wanted you, my golden bird!Or if a little Angel Boy

Came down and took you for his toy!He took the little soul that sings,

And only left the beak and wings.And so you died, and all the light

Ida Rentoul Outhwaite, Australian artist, 1931

Was covered with the big black night.

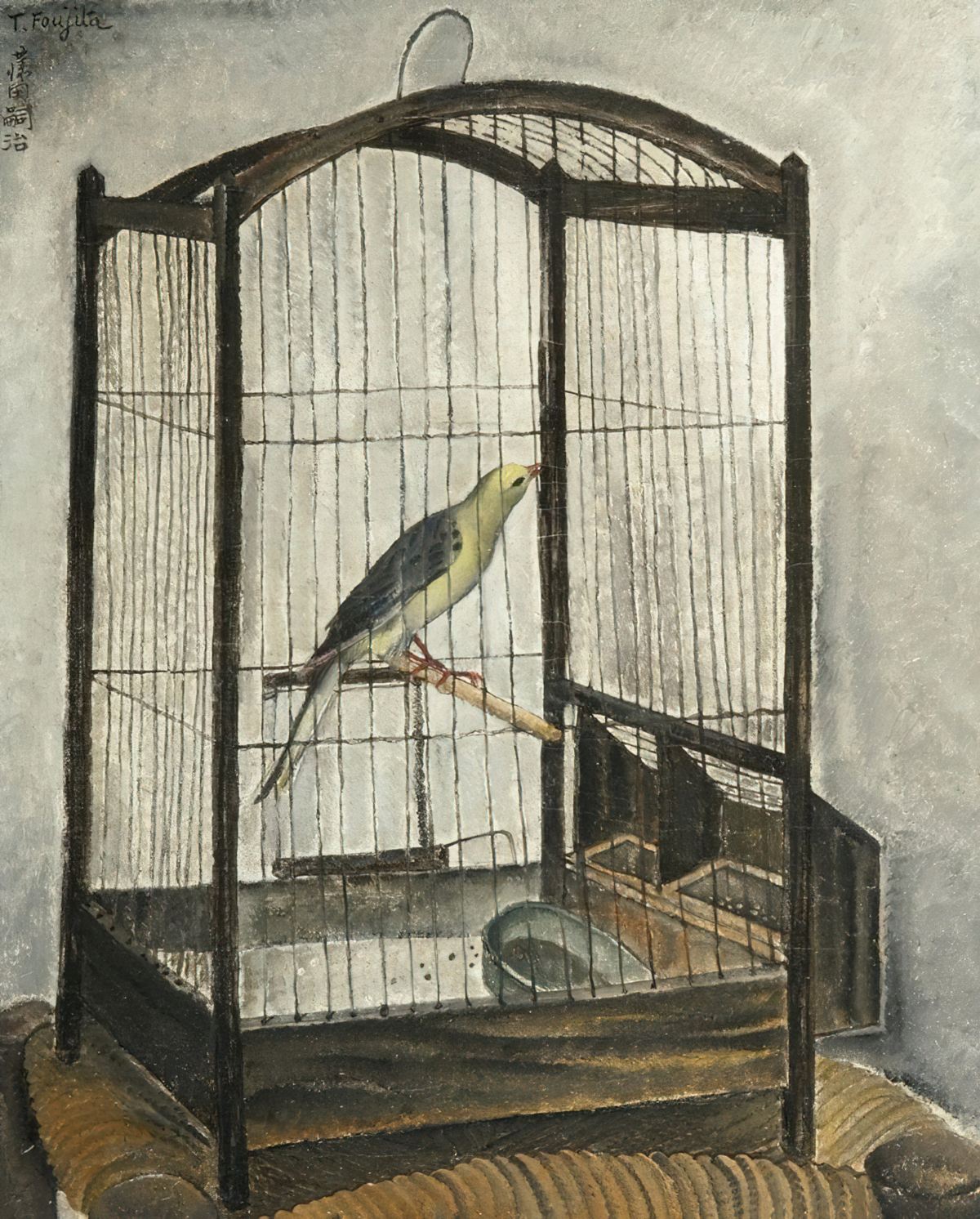

CAGED BIRDS VERSUS FREE BIRDS

Wilderness versus civilisation: The budgie in the cage is safe, warm and fed, but has no freedom. The bird outside lives precariously but enjoys freedom. Here the look at each other to determine what they do and don’t have. Humans do the same. What have we lost and gained by living as part of industrialised society?

I have to remind myself that some birds aren’t meant to be caged. Their feathers are just too bright. And when they fly away, the part of you that knows it was a sin to lock them up does rejoice. But still, the place you live in is that much more drab and empty once they’re gone.

Stephen King, The Shawshank Redemption

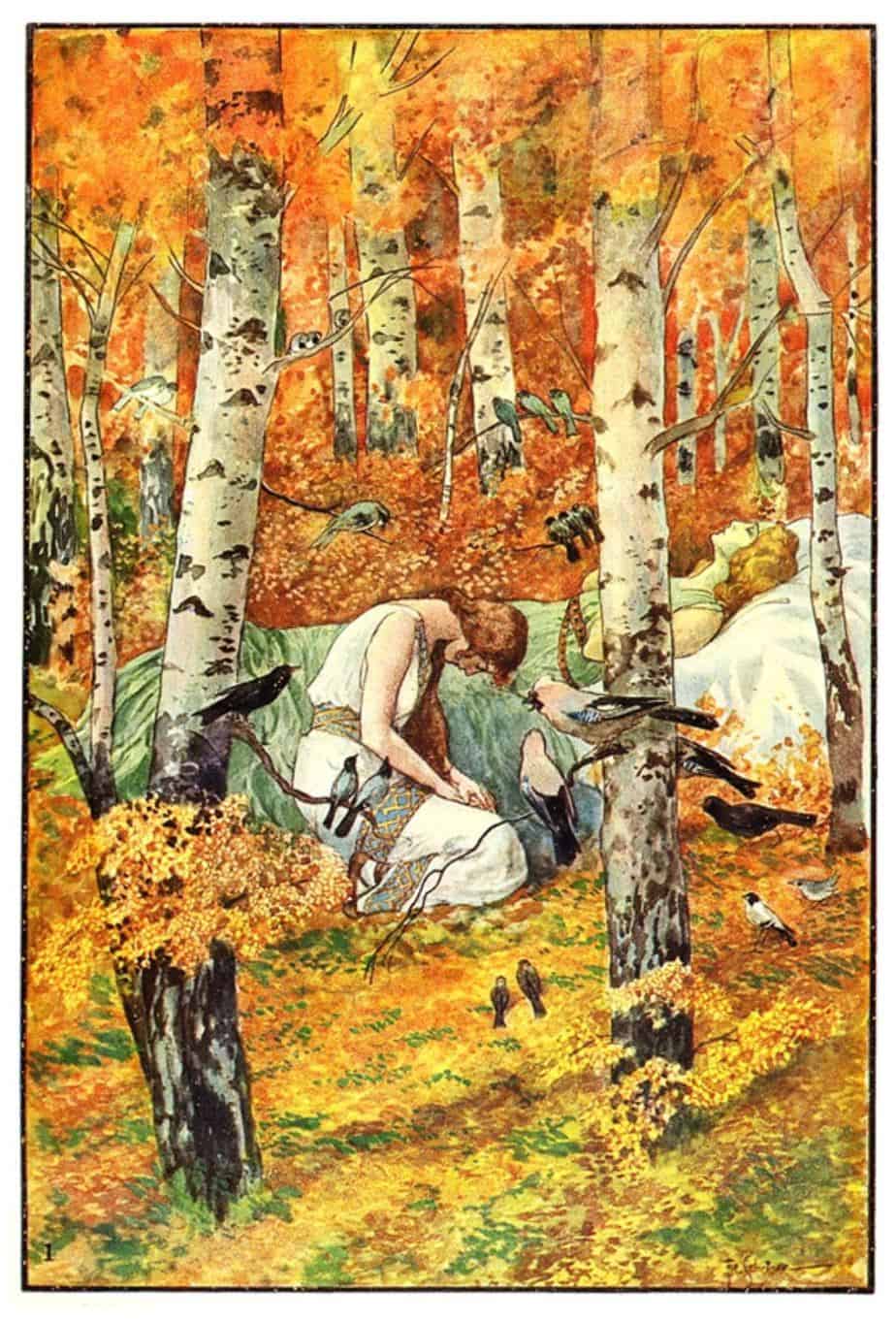

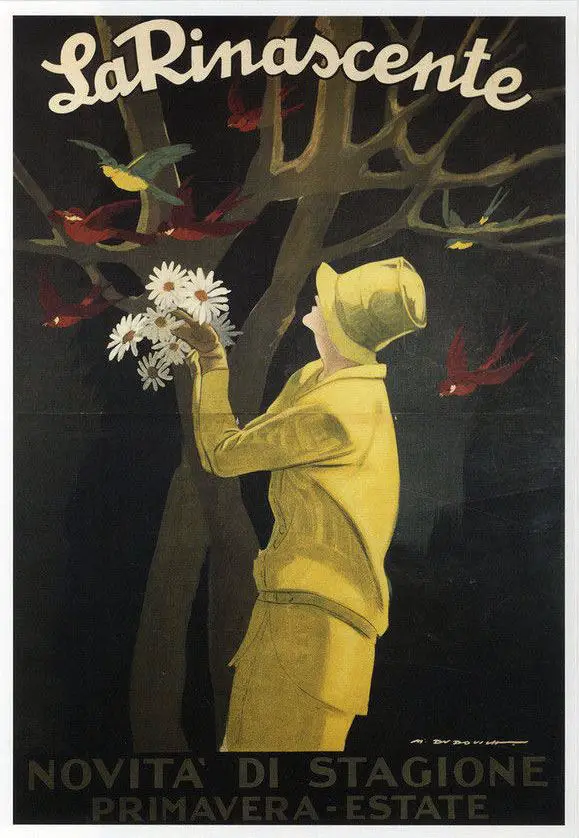

BIRDS AND FEMININITY

Even in modern literature, women are frequently compared to birds (and cats). There is a long history in art and storytelling of birds near women, women catching birds, women trying to catch birds… Why?

The image of Disney’s Snow White singing in the forest, so gentle and sweet that even the most timid of forest animals will approach her, is peak representation of the way we envisage perfect femininity: not one bit intimidating. So gentle and quiet, even a bird will land on her.

BIRDS AND THE MASCULINE

Weirdly, then: birds have historically been linked to the phallus. But hey, show me something that hasn’t! Birds (and also fish) were originally phallic symbols endowed with the power of “heightening” (getting closer to God, and ‘causing’ org*sm, I guess.)

Once you consider the 3000 year history of men as humans made in God’s image, and women as creatures connected to the earth, this isn’t surprising at all.

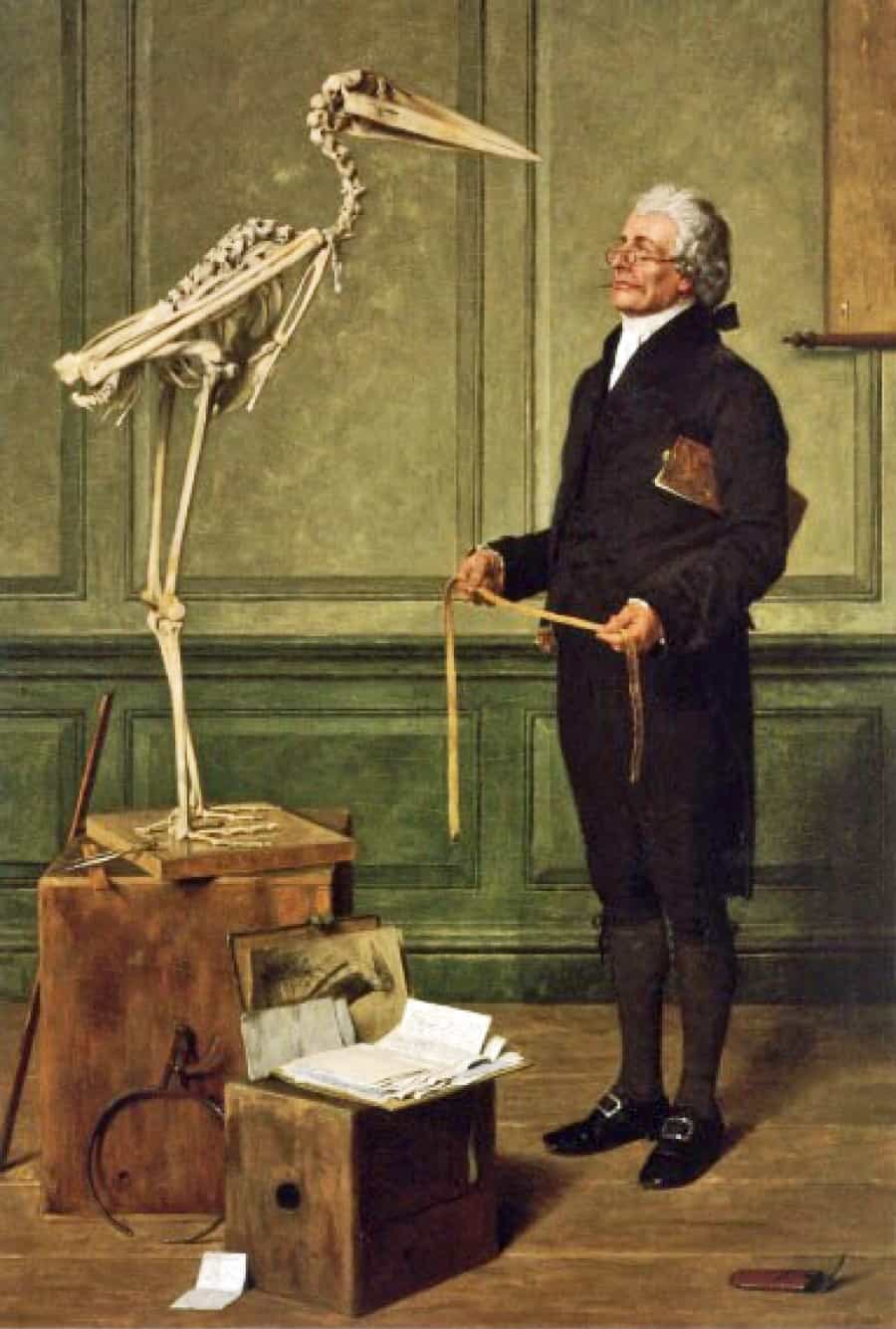

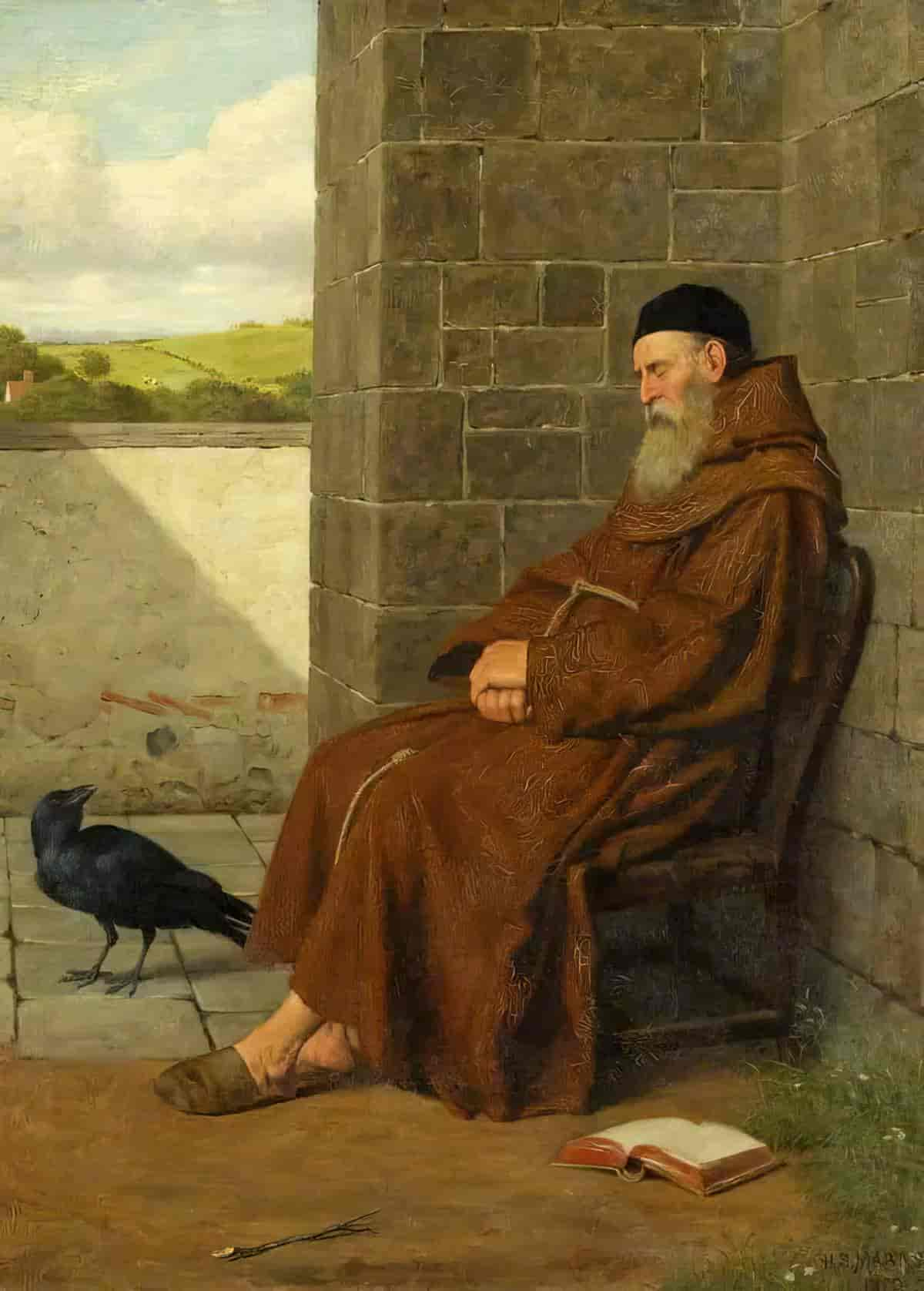

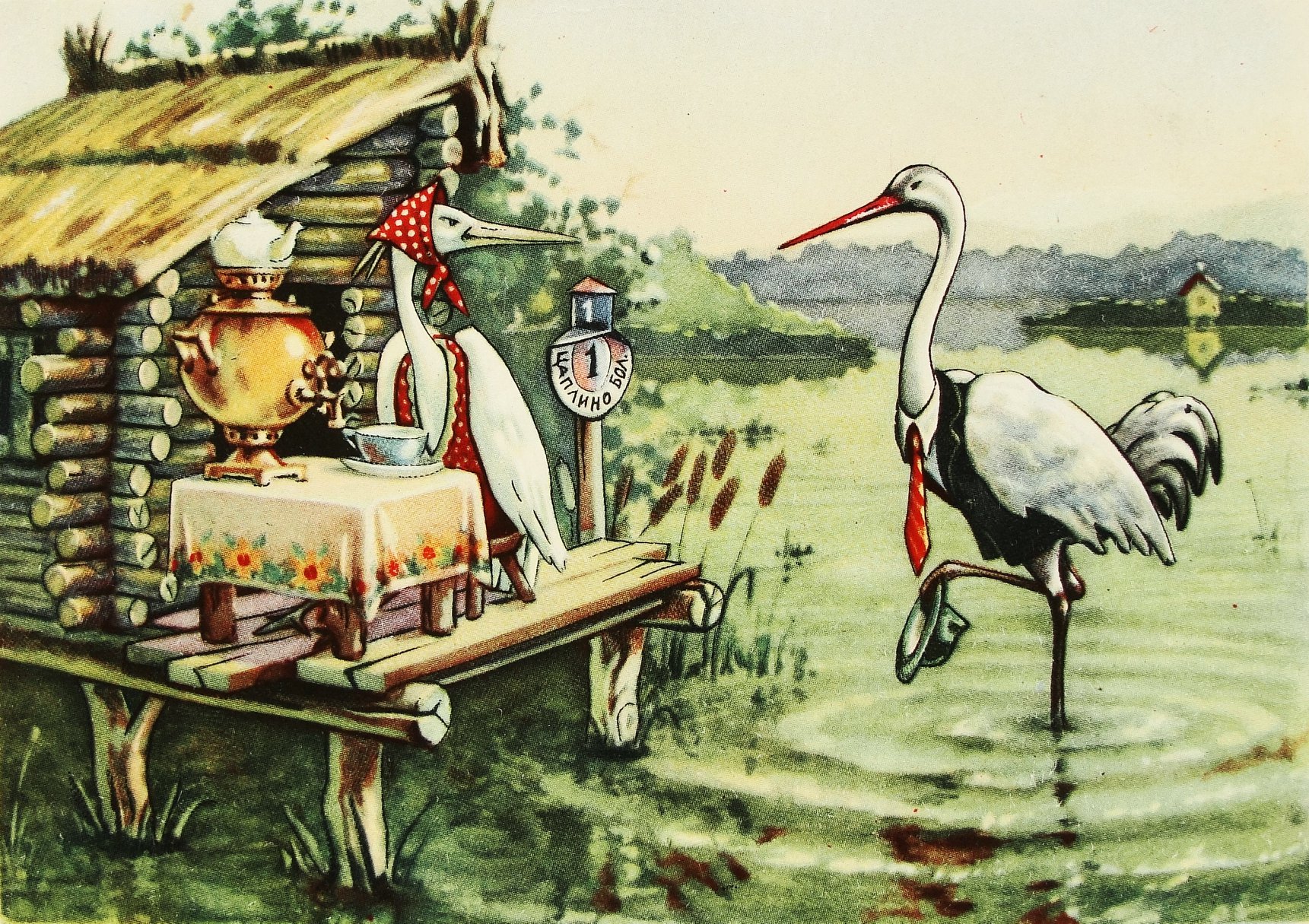

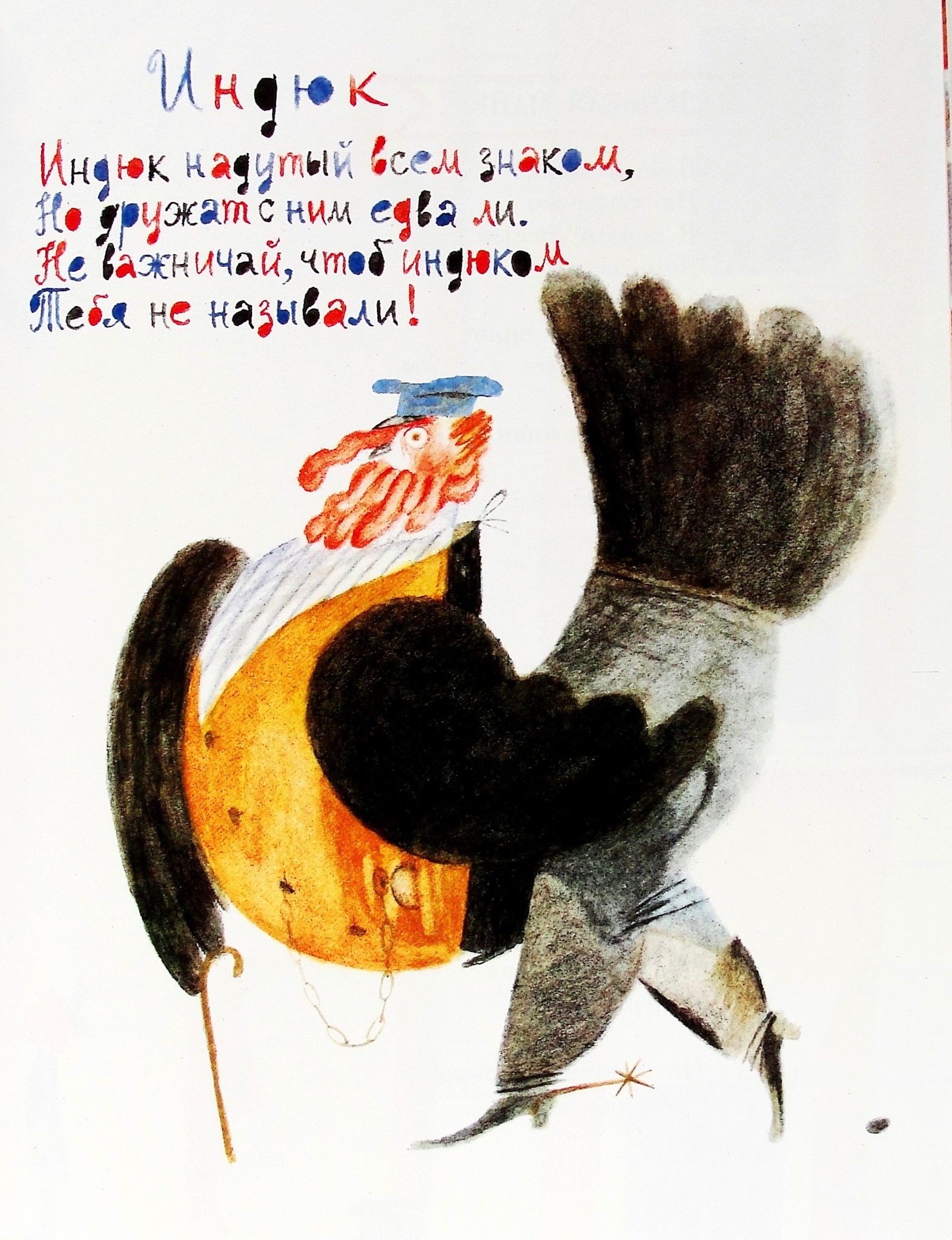

ANTHROPOMORPHISED BIRDS

In children’s stories animals are frequently given human characteristics, and certain kinds of animals crop up more than others. Birds are frequently anthropomorphised.

Birds have also been anthropomorphised by very serious philosophers.

Odo of Tusculum, in his sermon XCII, describes different kinds of spirituality in men in terms of the characteristics of different kinds of birds. Some birds, he says, are guileless, such as the dove; others, cunning like the partridge; some come to the hand, like the hawk, others flee from it, like the hen; some enjoy the company of men, like the swallow; others prefer solitude and the desert, like the turtle-dove. . . . Lowflying birds symbolize an earth-bound attitude; high-flying birds, spiritual longing.

Dictionary of Symbols by J.E. Circlot

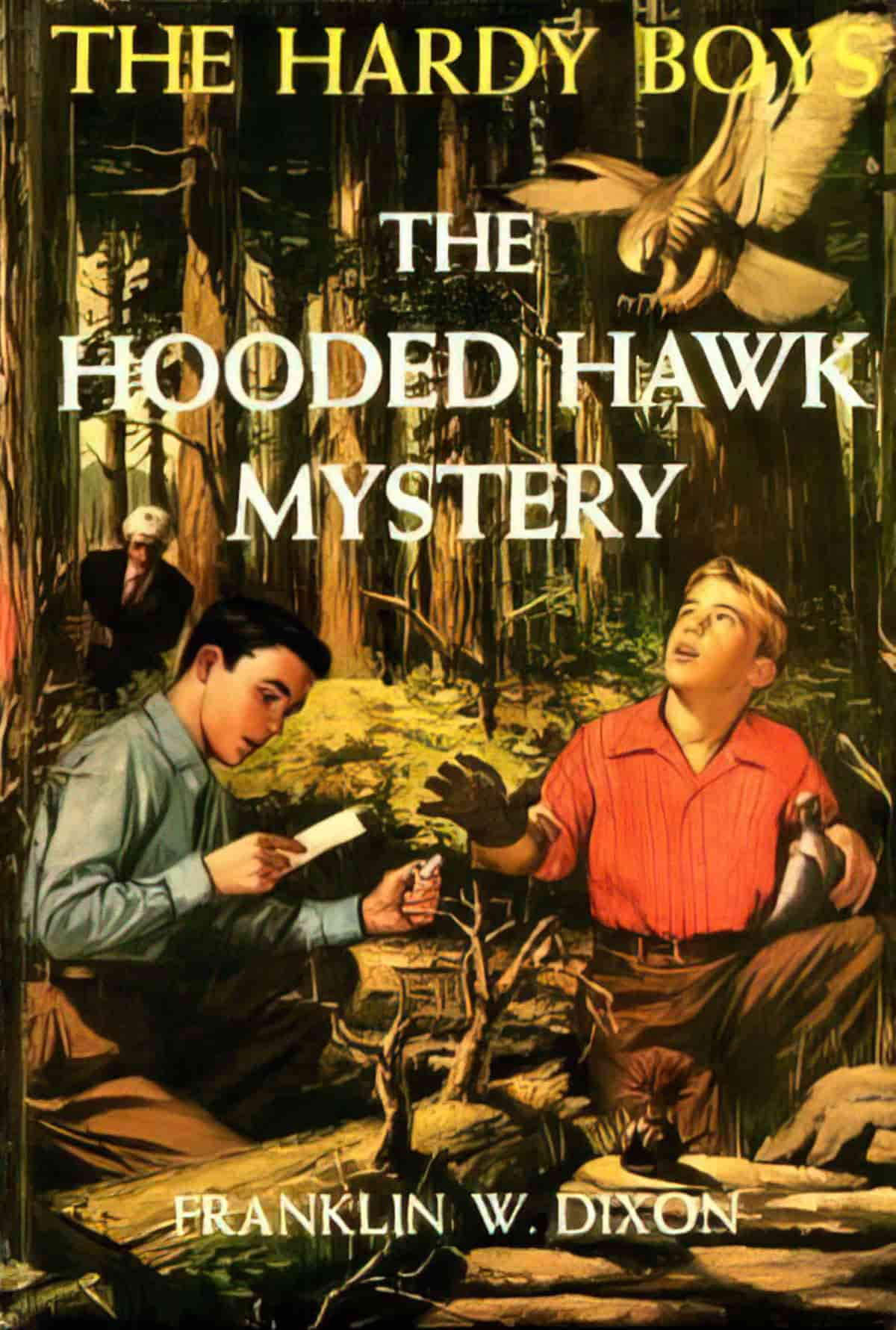

When their peregrine falcon brings down a homing pigeon carrying rubies, the Hardy brothers find themselves involved with kidnappers.

Birds wearing shoes are especially comical since they tend to fly, and therefore shouldn’t really need boots, huh?

BIRDS AND ALCHEMY

The ‘science’ of alchemy was all about birds and which direction they were flying:

- Soaring skywards: volatilization or sublimination

- Swooping earthwards: precipitation and condesnsation

Birds are considered volatile (rather than fixed).

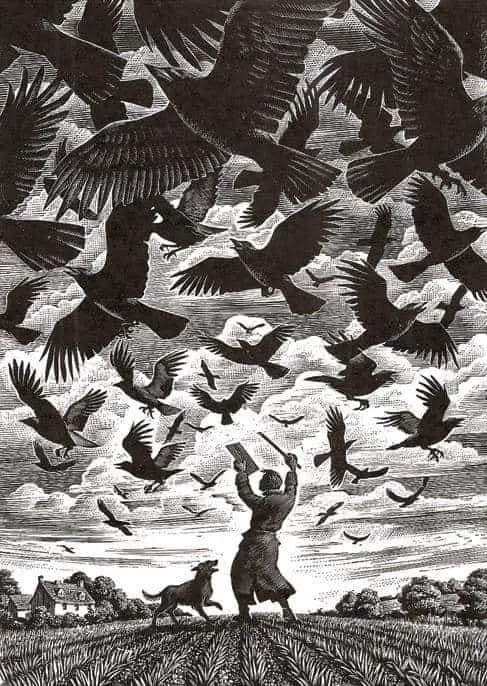

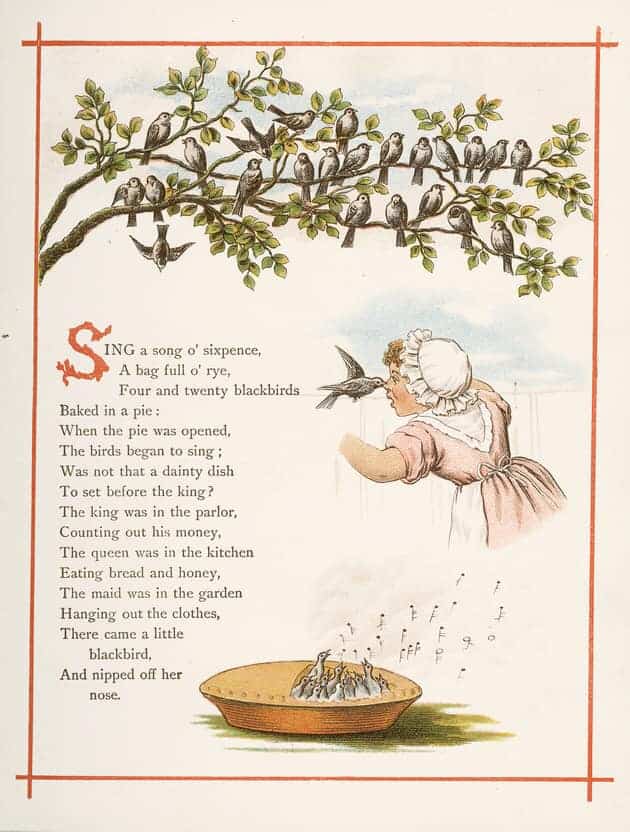

FLOCKS OF BIRDS

Be wary of flocks of birds. Multiplicity is a sign of the negative. A flock of bird is a bit too similar to a ‘swarm’ (of insects). We don’t want any teeming, thanks. Nothing teeming and restless.

In the legend of Hercules, birds rise up from Lake Stymphalus. This lake stands for the stagnation of the soul and paralysis of the spirit. The birds therefore point to wicked desires.

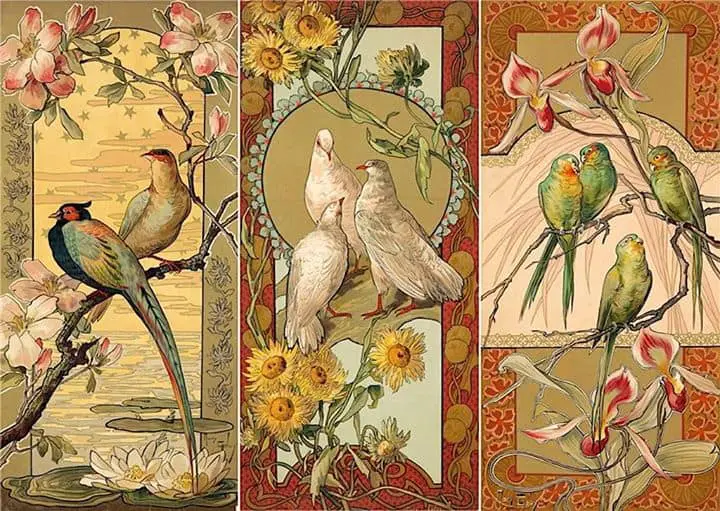

BIRDS AS CREATURES OF BEAUTY

Mary Golay- The Birds, 1900

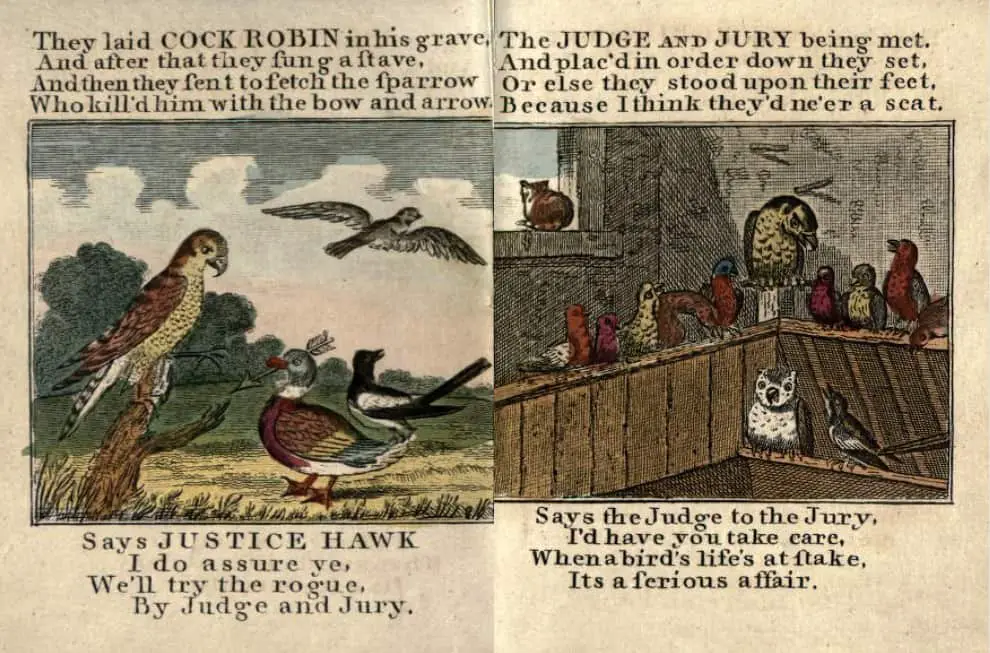

BIRDS AS HORROR VILLAINS

Long before Alfred Hitchcock ruined birds for many of us (especially during magpie season), Nursery Rhymes were doing a pretty good job of it.

BIRDS AND FREEDOM

“I wish I had the wings to fly away from here”

BIRDS AND THE UNGRASPABLE

In Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights, the motif of the thrush is used to symbolize the longing and nostalgia of the main character, Heathcliff.

BIRDS AND THEIR OPPONENTS

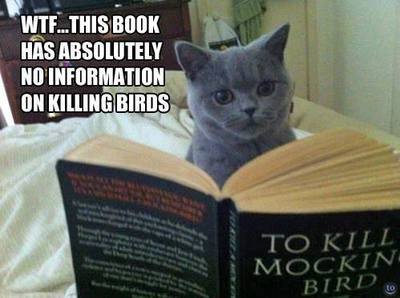

The archetypal opponent of the bird is the cat.

Snakes and serpents are also enemies of birds.

Header painting: VERNEUIL, Maurice Pillard (1869-1942). L’Animal dans la décoration. Paris- Librairie centrale des Beaux-arts, [1897] Birds Snails

THE HAWK

Hawking Women: Falconry, Gender, and Control in Medieval Literary Culture

Fantastic and informative talk with Sara Petrosillo of the University of Evansville about her new book, Hawking Women: Falconry, Gender, and Control in Medieval Literary Culture (Ohio State University Press, 2023). Listen all the way to the end for a great description of the process of hunting with birds! While critical discourse about falconry metaphors in premodern literature is dominated by depictions of women as unruly birds in need of taming, women in the Middle Ages claimed the symbol of a hawking woman on their personal seals, trained and flew hawks, and wrote and read poetic texts featuring female falconers.

Sara Petrosillo’s Hawking Women demonstrates how cultural literacy in the art of falconry mapped, for medieval readers, onto poetry and challenged patriarchal control. Examining texts written by, for, or about women, Hawking Women uncovers literary forms that arise from representations of avian and female bodies. Readings from Sir Orfeo, Chrétien de Troyes, Guillaume de Machaut, Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde, and hawking manuals, among others, show how female characters are paired with their hawks not to assert dominance over the animal but instead to recraft the stand-in of falcon for woman as falcon with woman. In the avian hierarchy female hawks have always been the default, the dominant, and thus these medieval interspecies models contain lessons about how women resisted a culture of training and control through a feminist poetics of the falconry practice.

New Books Network

THE AMERICAN BALD EAGLE

Caricature and National Character: The United States at War

Dr. Christopher Gilbert, Assistant Professor of English at Assumption College, has a new book that examines the understanding of American national character and culture through the works of caricature and comic representations. Gilbert specifically focuses on this kind of work that is produced during moments of crisis, particularly during wartime. Wartime often prompts self-understanding for a nation, since there is a demand that the reason for war is made clear, and the role of the nation is seen in this context. Gilbert notes that in the early days of the republic, Benjamin Franklin turned to caricature to help define or start to clarify an American national character, particularly in distinction from British colonial power. And this concept of national character is different than either patriotism or nationalism, since it reflects how citizens, individually and as a whole, understand themselves as a nation, and as separate from other nations. Unique histories, characteristics, and “belonging” all contribute to this broader sense of self for a nation.

Caricature and National Character: The United States at War (Pennsylvania State UP, 2021) examines the various symbols and images that have become part of the American national identity, noting, often, how those images shift and change with time and context. Gilbert notes that these recursive themes and images are distinct in different historical moments, providing a kind of complexity to the images and how and what they communicate. Consider the image of the bald eagle, which has been integrated into American national character for some time, but has been drawn and redrawn to represent imperialism, laziness, or cultural power at different points in U.S. history. Gilbert explains that humor itself is situational and situated, a sign or signal of the time, and that caricature and comic artists and political and editorial cartoonists are commenting on and positioning their work within a particular historical point, and in so doing, also reflecting American cultural politics.

Caricature and National Character brings a variety of artists together in a way that intertwines their work without silo-ing them within chronological periods. Their work is made, in a certain way, to be in conversation, and to help to understand the United States as a warring nation, even if there is no shooting war transpiring at times. The artists and cartoonists are using their own membership within the national character to present ideas and commentary on what it means, in time of war, to protect national character and what it is that needs protecting. These images, which can be explored across history, carry significant weight because they are reflecting on the notion of national character, which is often more clearly on display during times of war.

New Books Network

![VERNEUIL, Maurice Pillard (1869-1942). L'Animal dans la décoration. Paris- Librairie centrale des Beaux-arts, [1897] Birds Snails](https://www.slaphappylarry.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/VERNEUIL-Maurice-Pillard-1869-1942.-LAnimal-dans-la-decoration.-Paris-Librairie-centrale-des-Beaux-arts-1897-Birds-Snails.jpg)