What do ravens symbolise in art and literature. Also, how do different cultures view ravens?

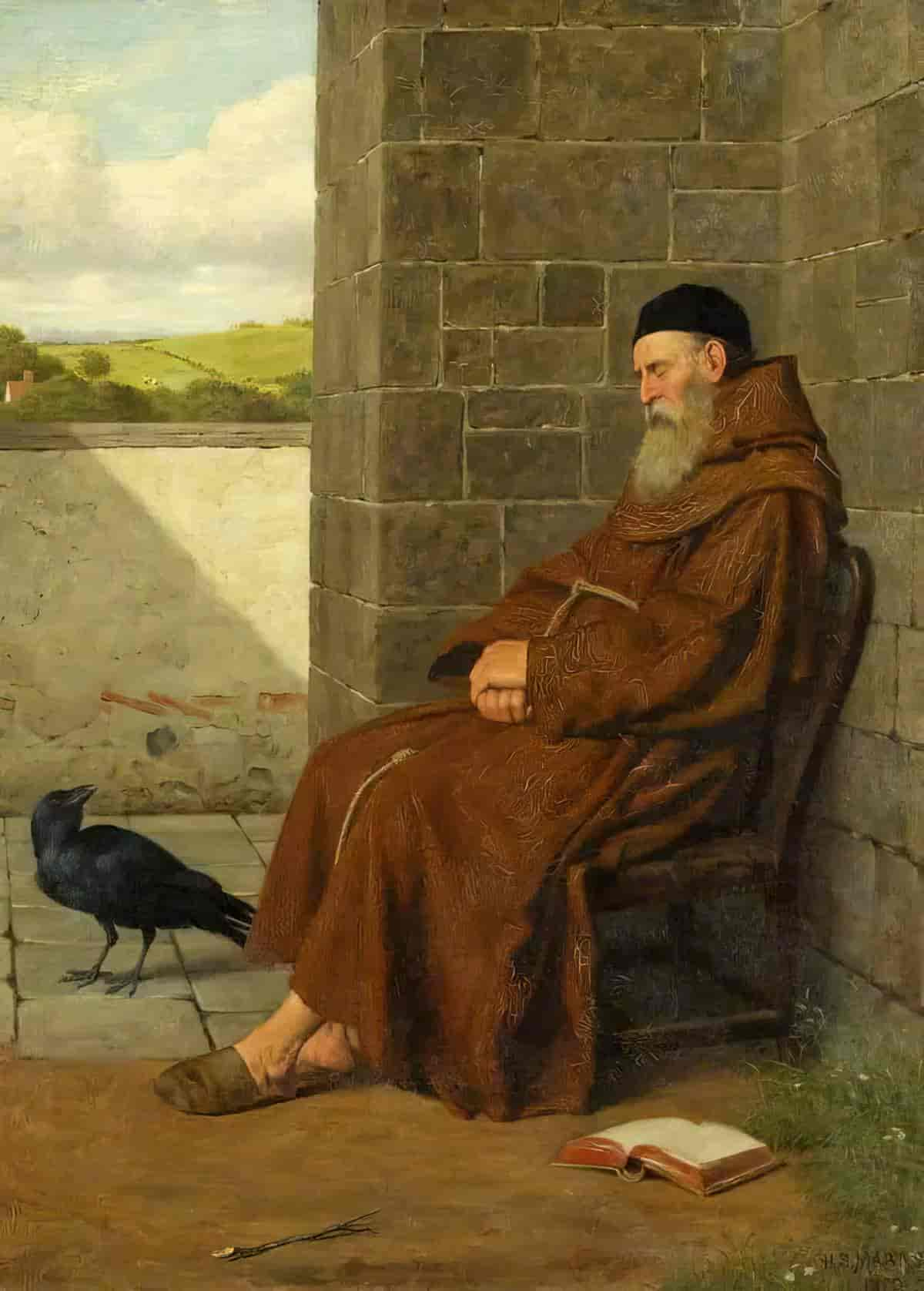

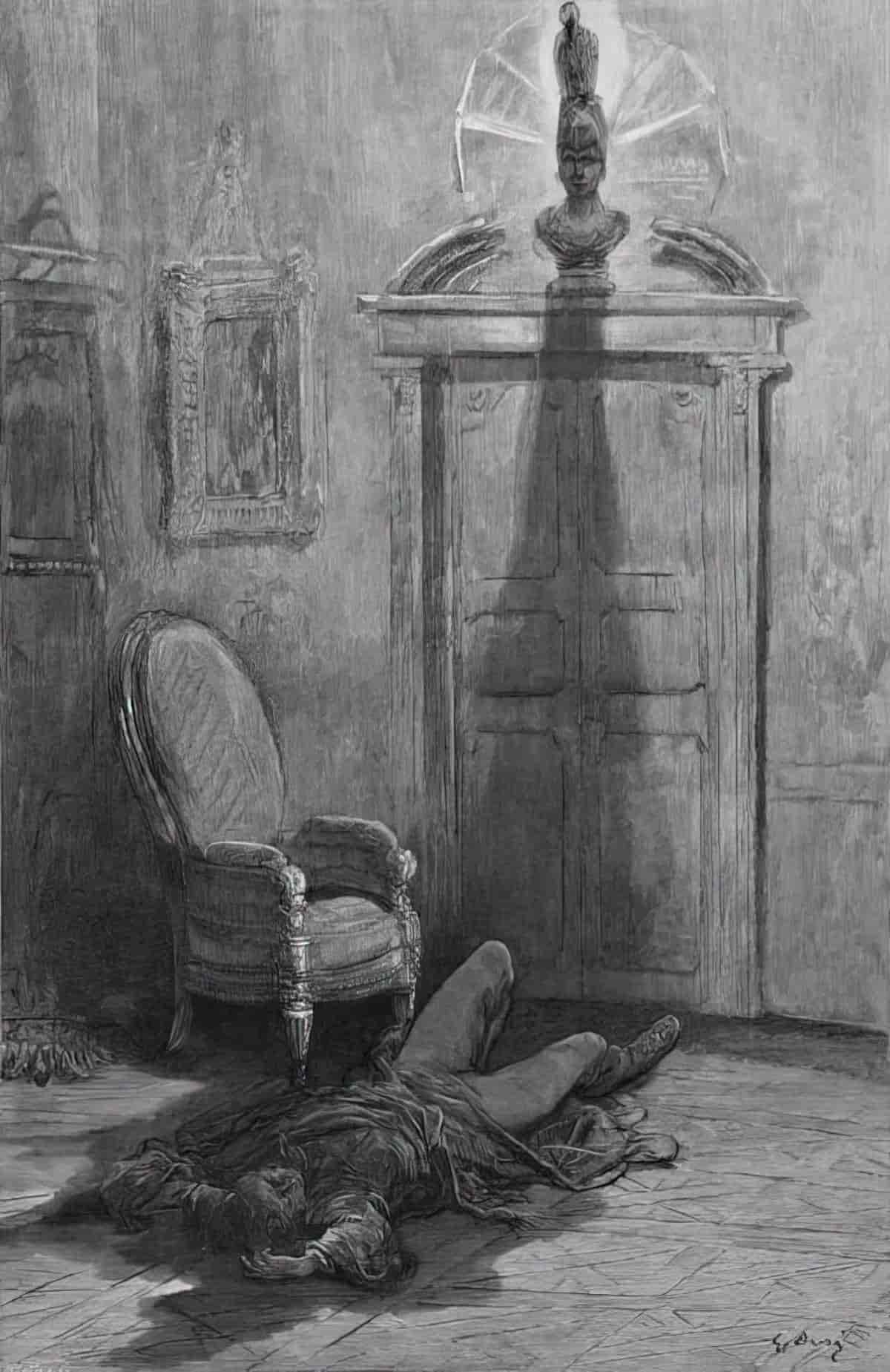

Notice anything creepy about this 1870 painting by Henry Stacey Marks? Do you think this elderly gentleman has long to live? What gives it away?

Raven as Designated SCARY BIRD

As the above painting shows us clearly, across Western art and literature, ravens are frequently associated with death. That makes them an omen of misfortune.

Two main reasons for this:

- They’re scavengers. Unlike crows they don’t tend to hang around where humans live, so humans see them most frequently around places of death, e.g. on battlefields.

- Their dark plumage. Black means death.

- Those massive beaks look like they could do some damage.

- The way they look at you.

- Alfred Hitchcock’s adaptation of “The Birds“.

According to an interview with Dick Cavett, Hitchcock admitted that roughly 3,200 real birds were trained for use in the film. Hitch also admitted that the ravens were the most clever, while the seagulls were the most ferocious.

10 Things You Never Knew About Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds, Screen Rant

If Margaret Atwood was a bird, she says she’d be a raven.

Other birds may have more vibrant plumage, but ravens are the intellectuals of the avian realm, the Canadian novelist says.

As her late husband Graeme Gibson’s “The Bedside Book of Birds” shows, Atwood said ravens have always occupied a storied place in human mythology, particularly as harbingers of misfortune and death.

Margaret Atwood on how late husband Graeme Gibson traced humanity’s avian obsession, 2021

Birds have always been a favourite device for prophecy and warning from the bird with bright feathers carrying the millstone in “The Juniper Tree” to Poe’s Raven. Birds have less obvious physical presence than animals — they may fly away or disappear, and seem naturally proud and arbitrary. In reality they often look arrogant, gay, heartless or beautiful — they seldom look humble unless there is something wrong with them; and there seems to be an unwritten law that magic animals are ancient, powerful, experienced, educated and erudite. Birds have this look, whether heraldic or real, from the Gryphon to Dudu the raven in Mrs Molesworth’s The Tapestry Room (1879).

Mrs Molesworth was, indeed, the first writer to take such a bird out of a fairy tale and place it in what one feels to be the right setting — a contemporary one. The Cuckoo Clock, written in 1877, has in it a bird character who besides being very moral is there in the clock. The arbiter of time, punctuality, rules and rightness, he is also there in a different kind of reality, always heralded by ‘the faint coming sound’ and able to take the lonely child Griselda on magic adventures. The old moral tales took a long time to fade; the Cuckoo from the clock insists on Griselda’s doing as she is old, attending to her lessons and being patient. But he provides the companionship she needs until she is lonely no longer and he can turn once more to wood. He is stern, logical and philosophical.

Margaret Blount, Animal Land

For an example of raven as death in children’s picture books, check out Norton’s Hut by John Marsden and Peter Gouldthorpe.

A school group of young hikers caught in a blizzard in the mountains take shelter in an unnamed hut, but find they are not alone. There is a stranger warming his hands by the fire. The stranger is silent, ignoring them, while outside the hut the storm rages…. This is the second picture book for internationally bestselling children’s author, John Marsden. His verse ghost story evokes the mystery of the high country and is illustrated in spectacular oils by leading illustrator, Peter Gouldthorpe.

Wisdom and Knowledge

While Western literature associates ravens with death and bad stuff, not everyone does this.

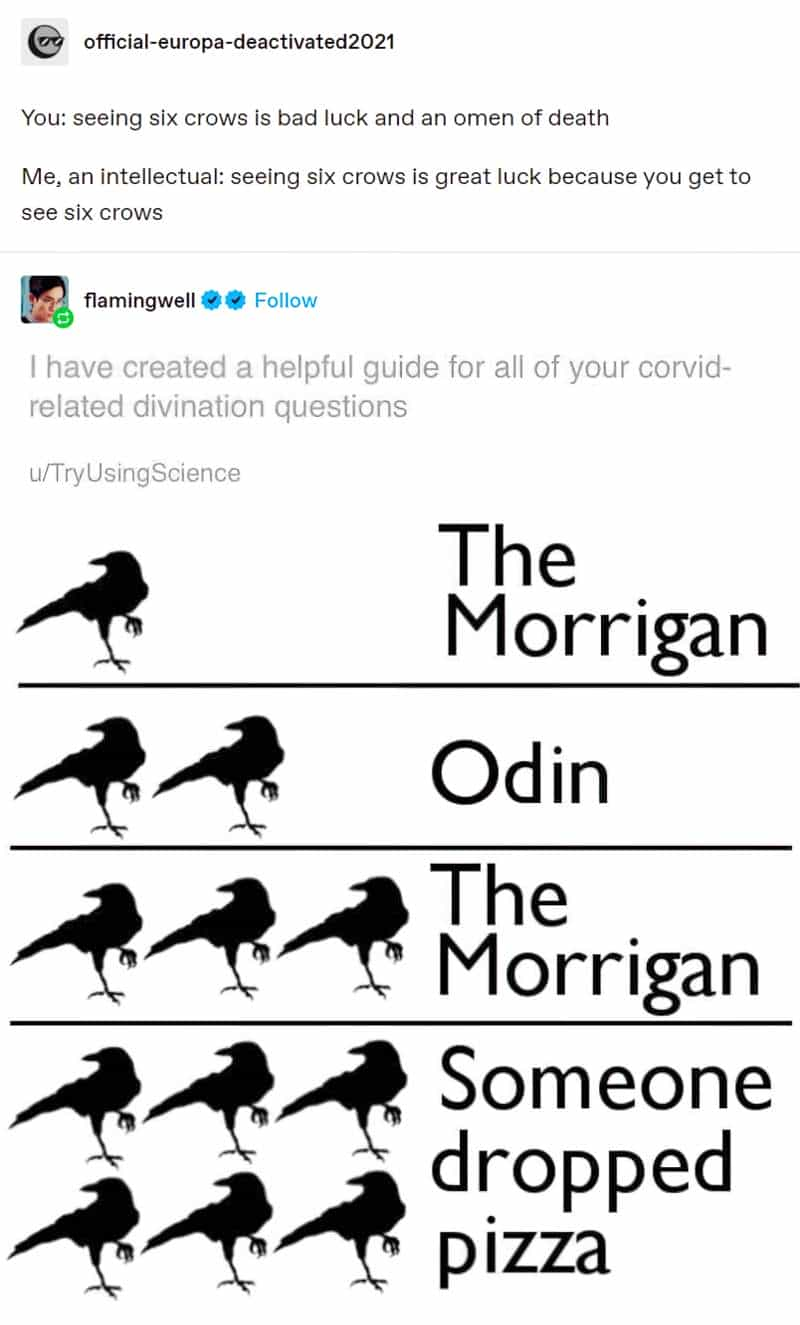

Some cultures, notably Native American cultures and in Norse mythology, the raven is a symbol of wisdom.

In Norse mythology, Odin, the chief of the Aesir gods, had two ravens, Huginn (thought) and Muninn (memory), which flew around the world to bring him information.

Hrafn (Old Norse pronunciation: [ˈhrɑvn]; Icelandic pronunciation: [ˈr̥apn̥]) is both a masculine byname, and personal name in Old Norse.

(The Germanic first names “Bertram” and “Wolfram” both derive from the Old High German word “hram”, meaning raven. I would’ve guessed the name Wolfram is related to ‘wolf’, but no.)

Cementing their status as the most terrifying of all the birds, a new study has found that ravens are able to imagine being spied upon — a level of abstraction that was previously thought to be unique to humans.

Ravens have paranoid, abstract thoughts about other minds, Wired

Voracious Appetite

The word ‘raven’ is related to ‘ravenous’. Both words come from the Old French word raviner which means ‘to pillage’. As an archaic English verb, ‘to raven’ means to hunt voraciously for prey.

Check out the entry for Raven at Etymology Online.

Transformation and Rebirth

The raven’s ability to transform and adapt to various environments, as well as its association with scavenging, has led to its symbolism of transformation and rebirth.

In some cultures, the raven is a messenger between the living and the spirit world.

Raven as Trickster

In Native American and some other indigenous mythologies, the raven is often portrayed as a trickster figure.

In folk and fairytale, tricksters are unpredictable, fun to watch, and clever. They also mark the delicate balance between chaos and order.

Stieg Larsson’s Millennium trilogy and Suzanne Collins’s “Hunger Games” series have given us female tricksters, women who are quick-witted, fleet-footed, and resolutely brave. Like their male counterparts—Coyote, Anansi, Raven, Rabbit, Hermes, Loki, and all those other mercurial survivors—these women are often famished (bulimic binges are their update on the mythical figure’s ravenous appetite), but also driven by mysterious cravings that make them appealingly enigmatic. Surrounded by predators, they quickly develop survival skills; they cross boundaries, challenge property rights, and outwit all who see them as easy prey. But, unlike their male analogues, they are not just cleverly resourceful and determined to survive. They’re also committed to social causes and political change.

Maria Tatar

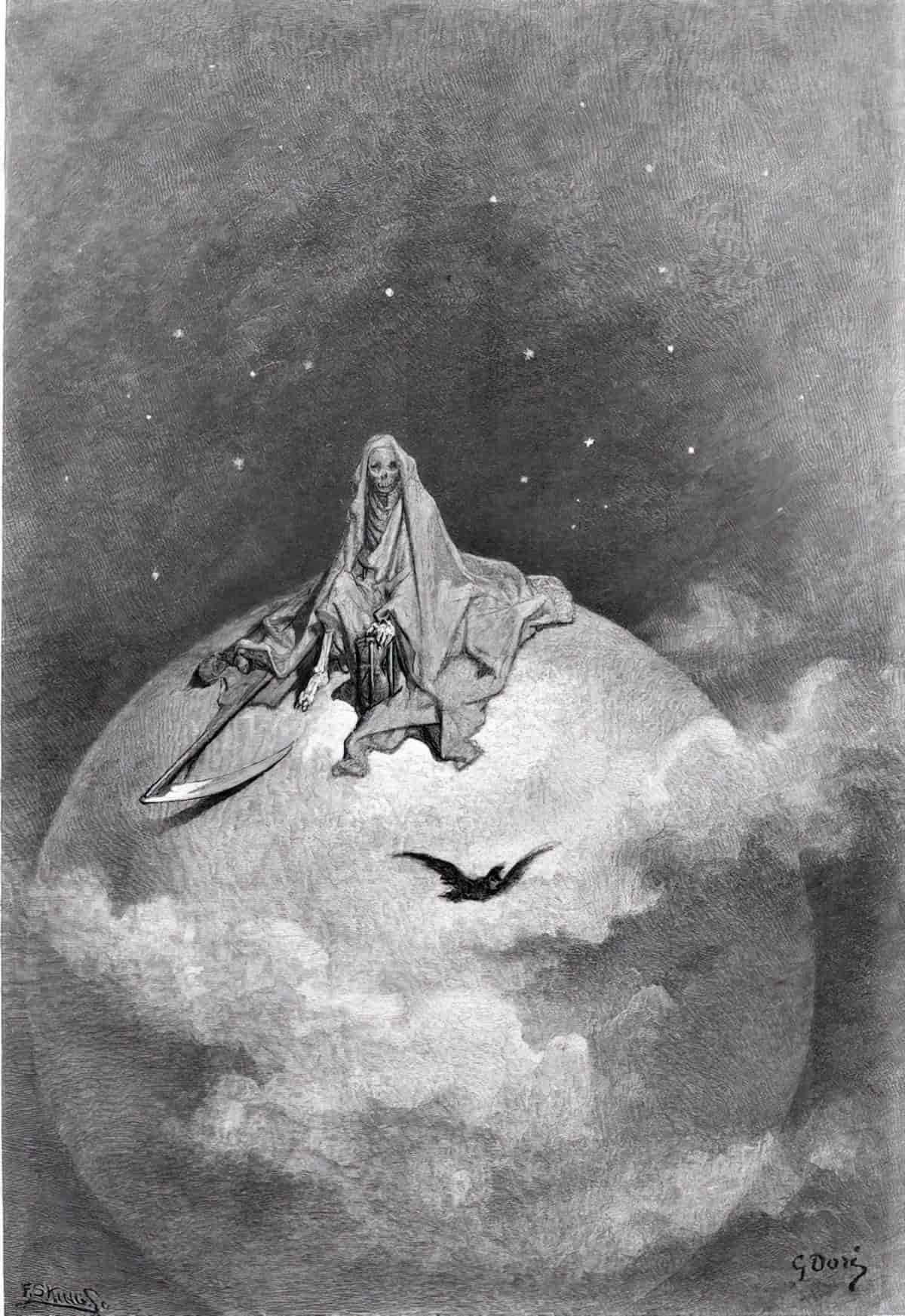

Magic and the Occult

Ravens have been associated with magic and the occult across various traditions. Their presence in folklore and mythology is often linked to their mystical qualities.

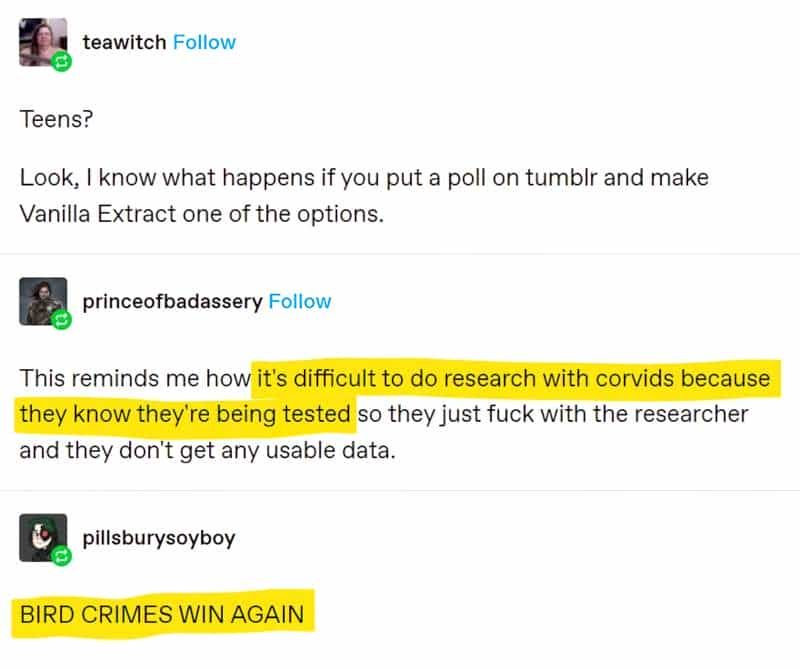

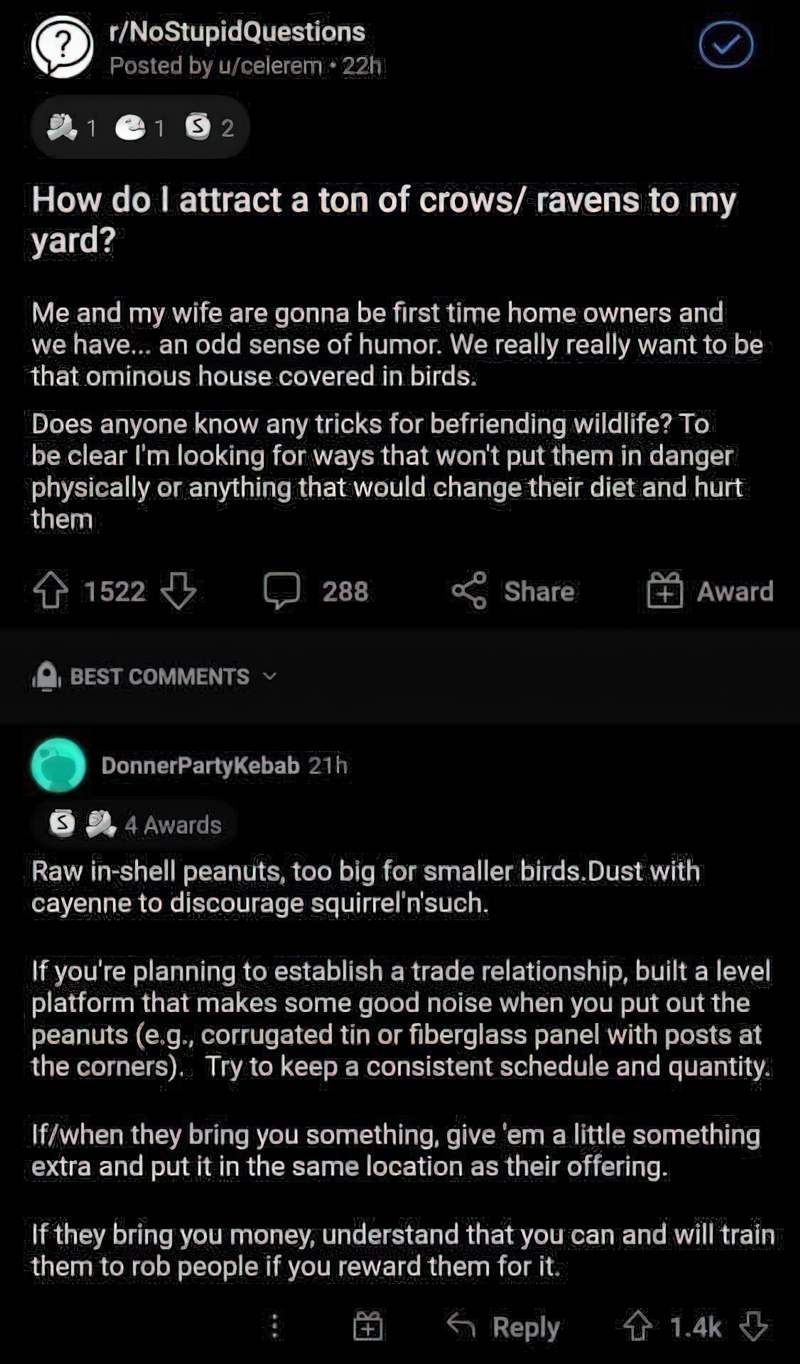

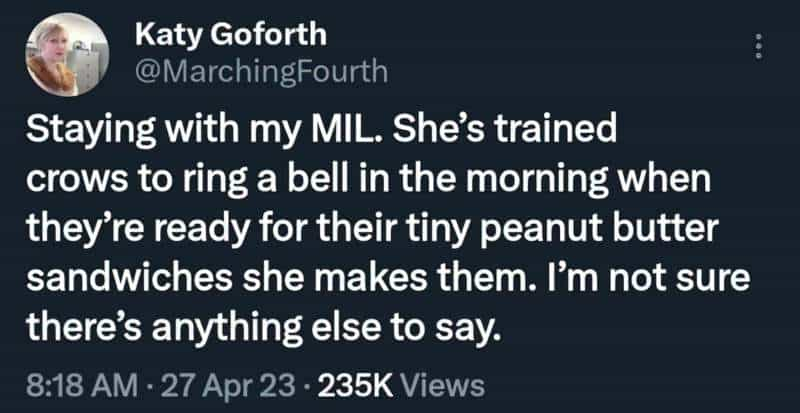

Intelligence and Adaptability

Ravens are scary smart birds, known for their problem-solving abilities. Think: adaptability, resourcefulness, cunning.

A study published in 2017 in the journal Science revealed that ravens pre-plan tasks—a behaviour long believed unique to humans and their relatives. (National Geographic Magazine)

Whereas dogs as companions in children’s literature tend to be true companions, when birds fill this role they tend to be more than friends — they’re more like ‘engineers of children’s fates’.

THE RAVEN IN THE OLD TESTAMENT

Remember that dove which Noah sent out, to see if the waters had subsided elsewhere? Everyone knows of that dove, because we see it depicted in art holding an olive leaf in its beak. Less memorable, for me at least, is the raven. Remember that? Noah sent out the raven first but it never came back. He only sent that dove out a week later. When he sent the dove out again and it didn’t come back this time, he knew waters had subsided enough for the bird to find somewhere on land.

I wonder what was supposed to have happened to that raven. Ravens today are super smart birds. I think maybe the raven was smarter than the dove and found dry land more easily. That’s why it never came back!

There’s more to this literary symbolism, of course. The raven is black and that dove is white. Ravens = bad, doves = peace. This is seen over and over again throughout our history of storytelling.

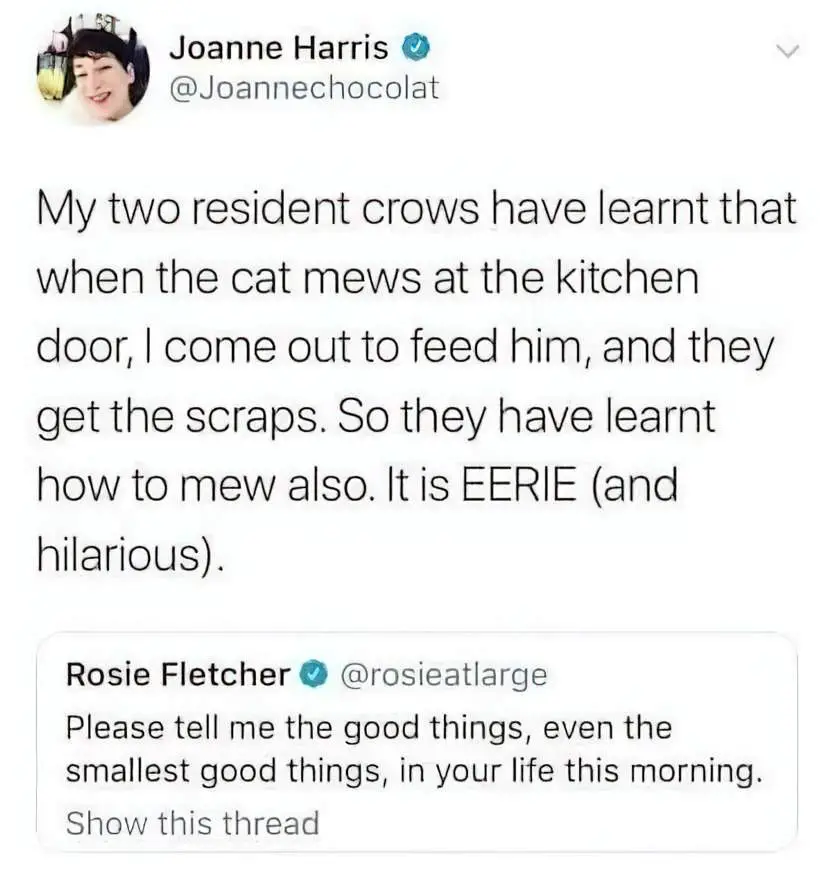

Communication

The raven’s vocalizations and mimicry skills have led to it being associated with communication and the ability to convey messages or warnings.

At a wildlife rehab facility I met two crows that said, “caw” in a human accent. They said it like a human reading the word “caw” aloud. The tech shook her head and said, “they’re making fun of us. People say ‘caw’ to them all day, so they’ve started impersonating us.” I <3 crows

@CryptoNature (Crows and ravens are both members of the Corvidae family.)

CAN RAVENS REALLY TALK?

They have a vast repertoire of 100 or more vocalizations. With their deep voice, ravens can mimic human speech and singing and can imitate other bird sounds. They call to inform their mate to join them when food is found.

5 Fascinating Facts About Ravens

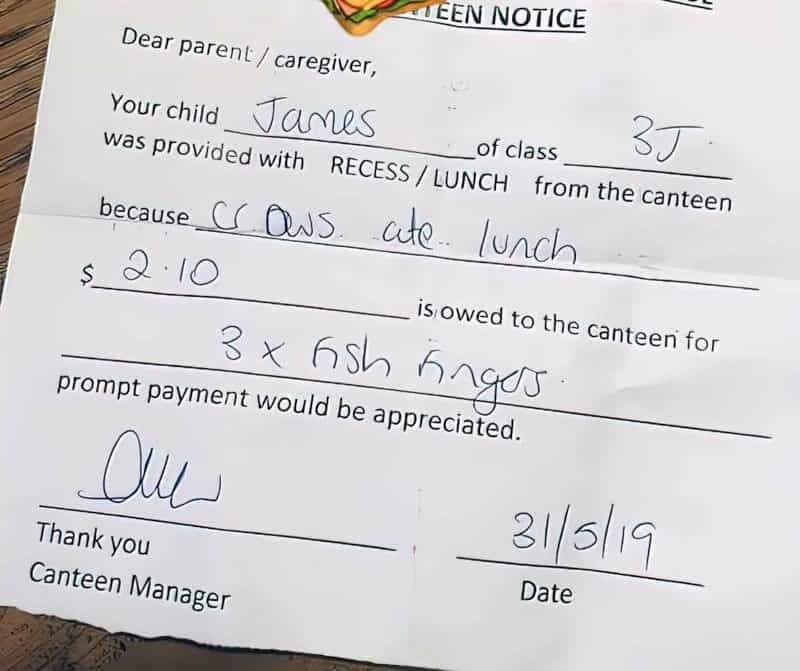

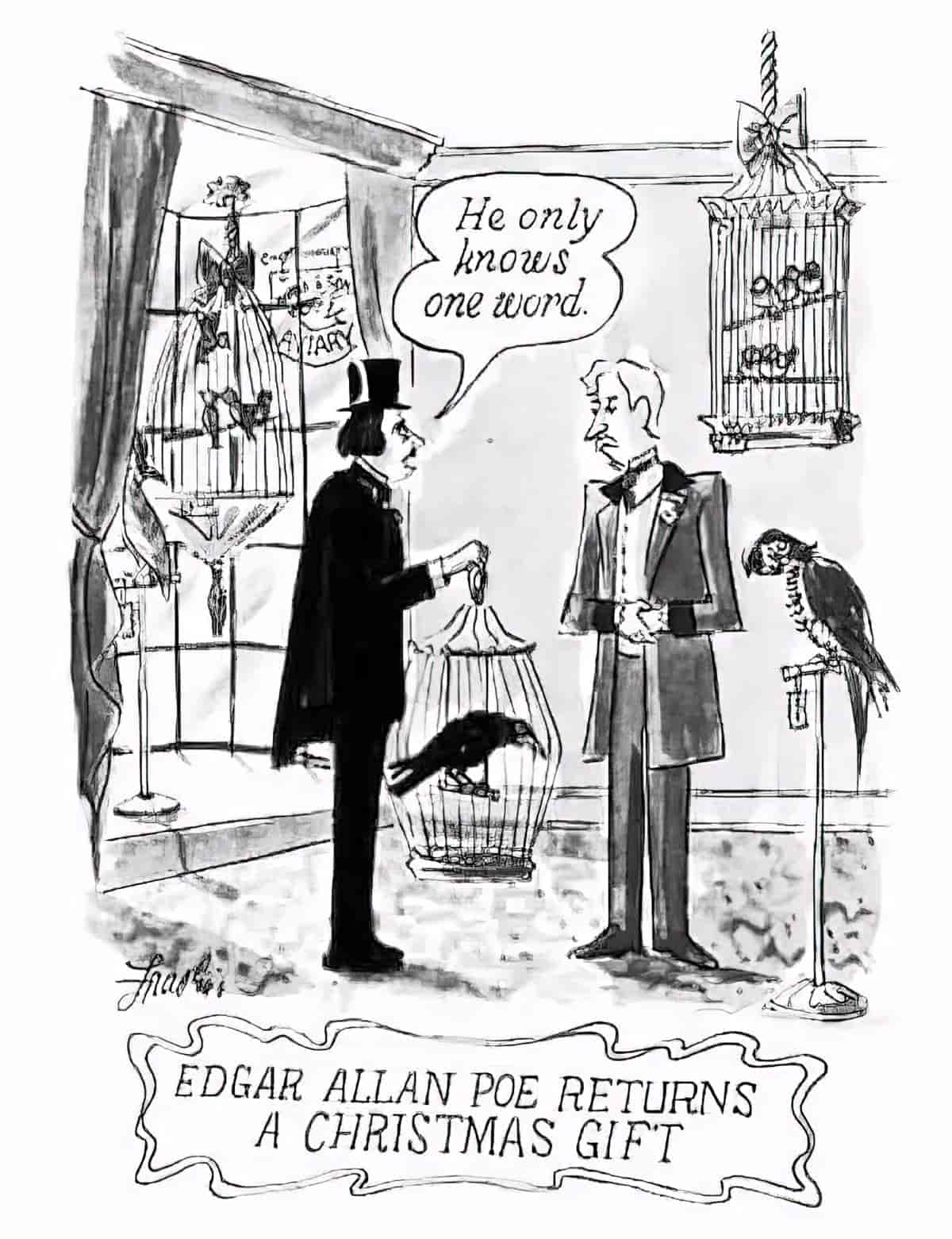

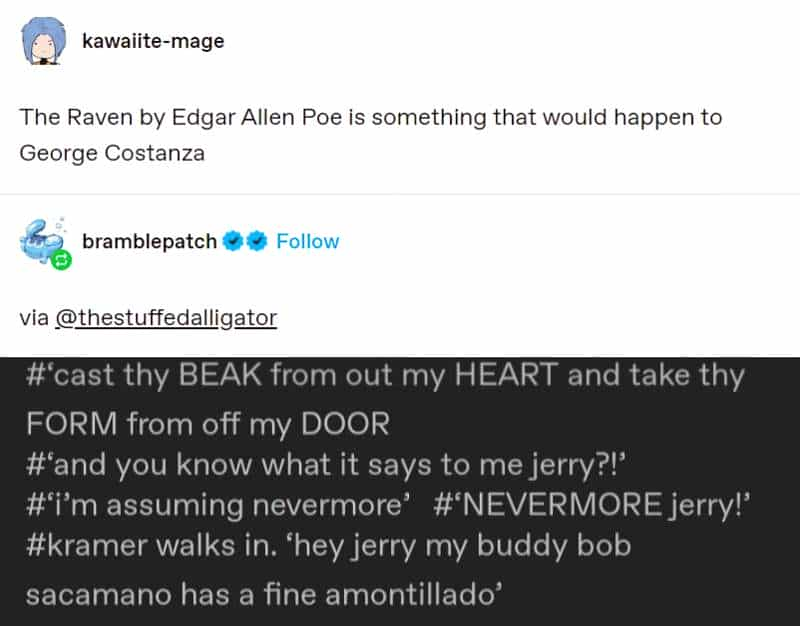

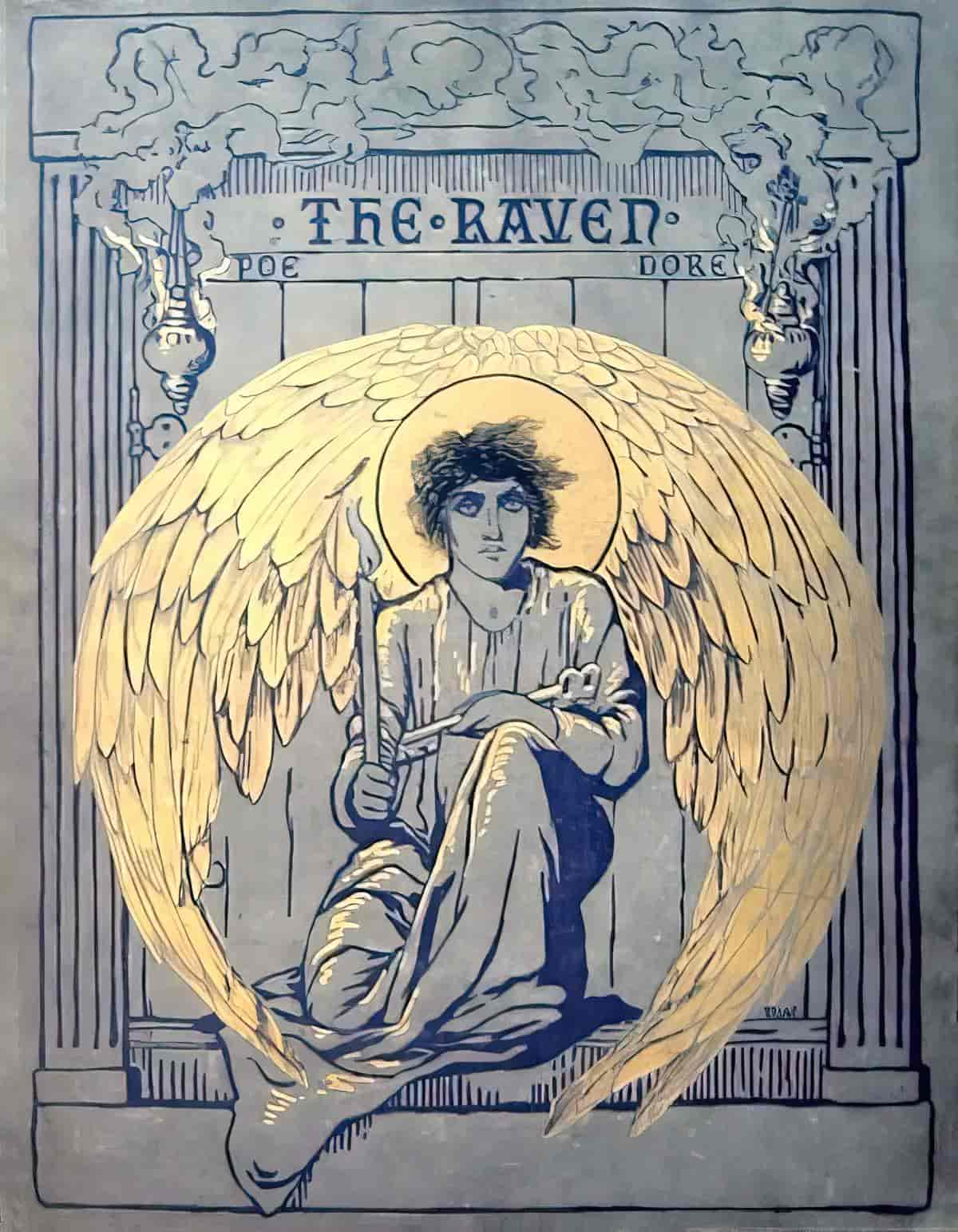

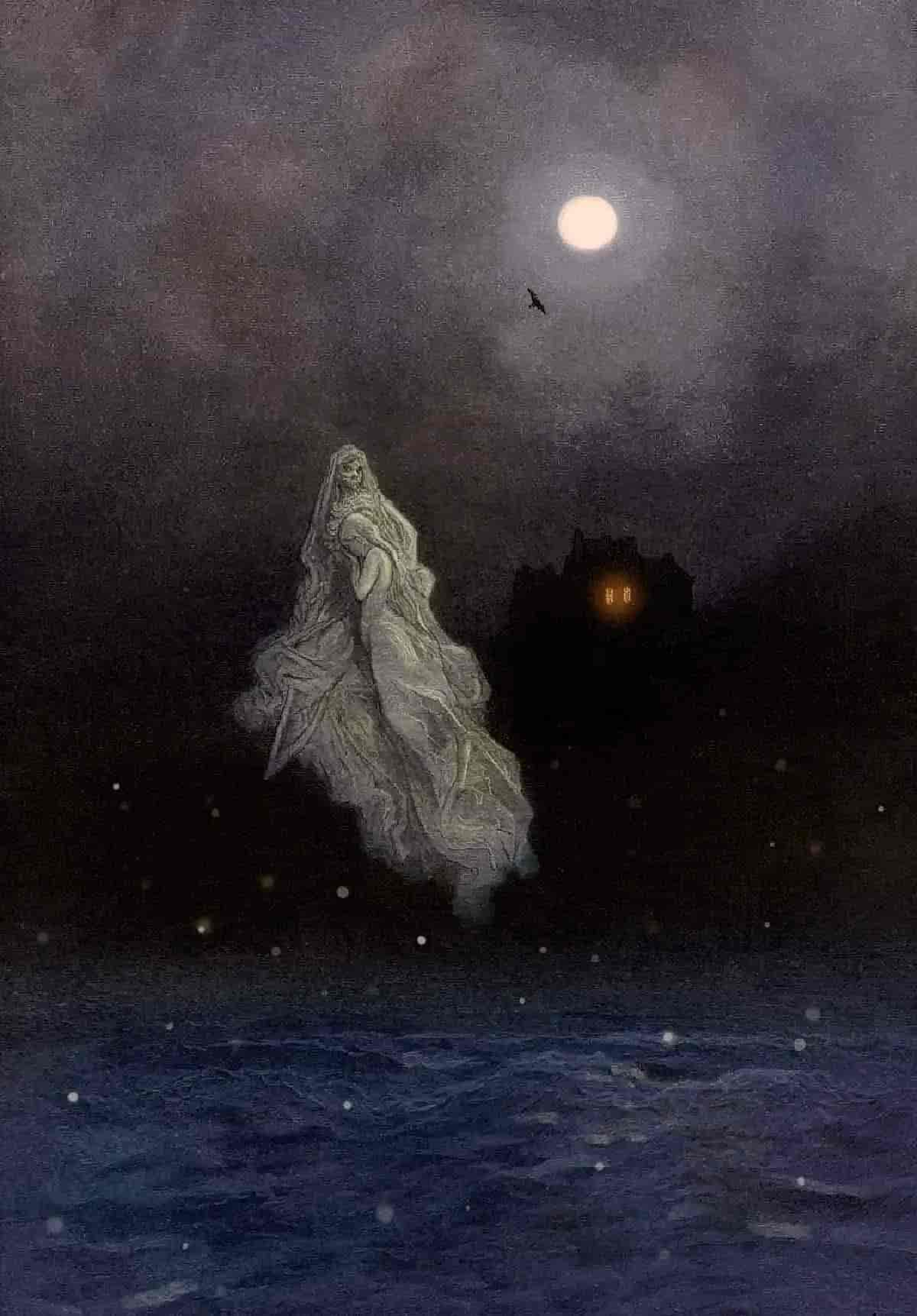

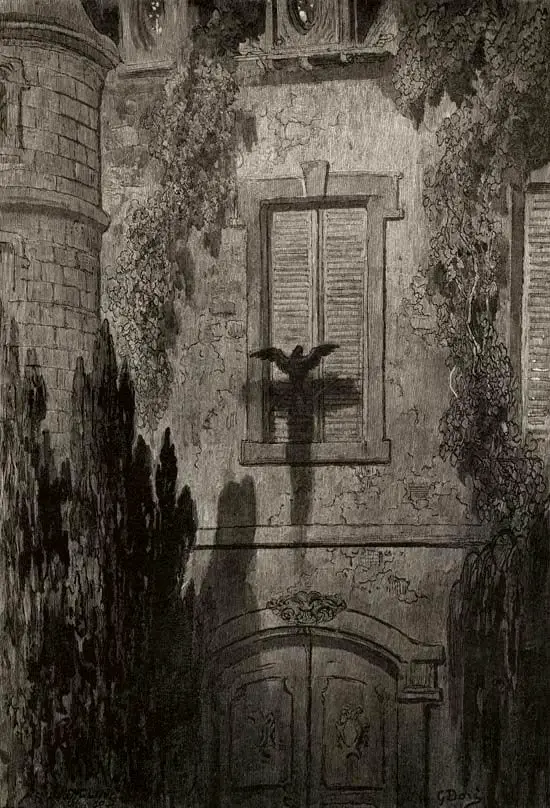

“THE RAVEN” BY EDGAR ALLAN POE

Edgar Allan Poe’s poem “The Raven” is one of his most famous works and if we’re talking about ravens, we cannot go past it.

- Basically, a man is visited by a talking raven that speaks the word “Nevermore”.

- The poem is written in trochaic octameter, which gives it a singsong and almost hypnotic quality.

- The rhyme scheme is ABCBBB.

- “The Raven” illustrates the narrator’s descent into madness.

Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary,

Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore—

While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping,

As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door.

“’Tis some visitor,” I muttered, “tapping at my chamber door—

Only this and nothing more.”Ah, distinctly I remember it was in the bleak December;

And each separate dying ember wrought its ghost upon the floor.

Eagerly I wished the morrow;—vainly I had sought to borrow

From my books surcease of sorrow—sorrow for the lost Lenore—

For the rare and radiant maiden whom the angels name Lenore—Nameless here for evermore.And the silken, sad, uncertain rustling of each purple curtain

Thrilled me—filled me with fantastic terrors never felt before;

So that now, to still the beating of my heart, I stood repeating

“’Tis some visitor entreating entrance at my chamber door—

Some late visitor entreating entrance at my chamber door;—

This it is and nothing more.”Presently my soul grew stronger; hesitating then no longer,

“Sir,” said I, “or Madam, truly your forgiveness I implore;

But the fact is I was napping, and so gently you came rapping,

And so faintly you came tapping, tapping at my chamber door,

That I scarce was sure I heard you”—here I opened wide the door;—

Darkness there and nothing more.Deep into that darkness peering, long I stood there wondering, fearing,

Doubting, dreaming dreams no mortal ever dared to dream before;

But the silence was unbroken, and the stillness gave no token,

And the only word there spoken was the whispered word, “Lenore?”This I whispered, and an echo murmured back the word, “Lenore!”—

Merely this and nothing more.Back into the chamber turning, all my soul within me burning,

Soon again I heard a tapping somewhat louder than before.

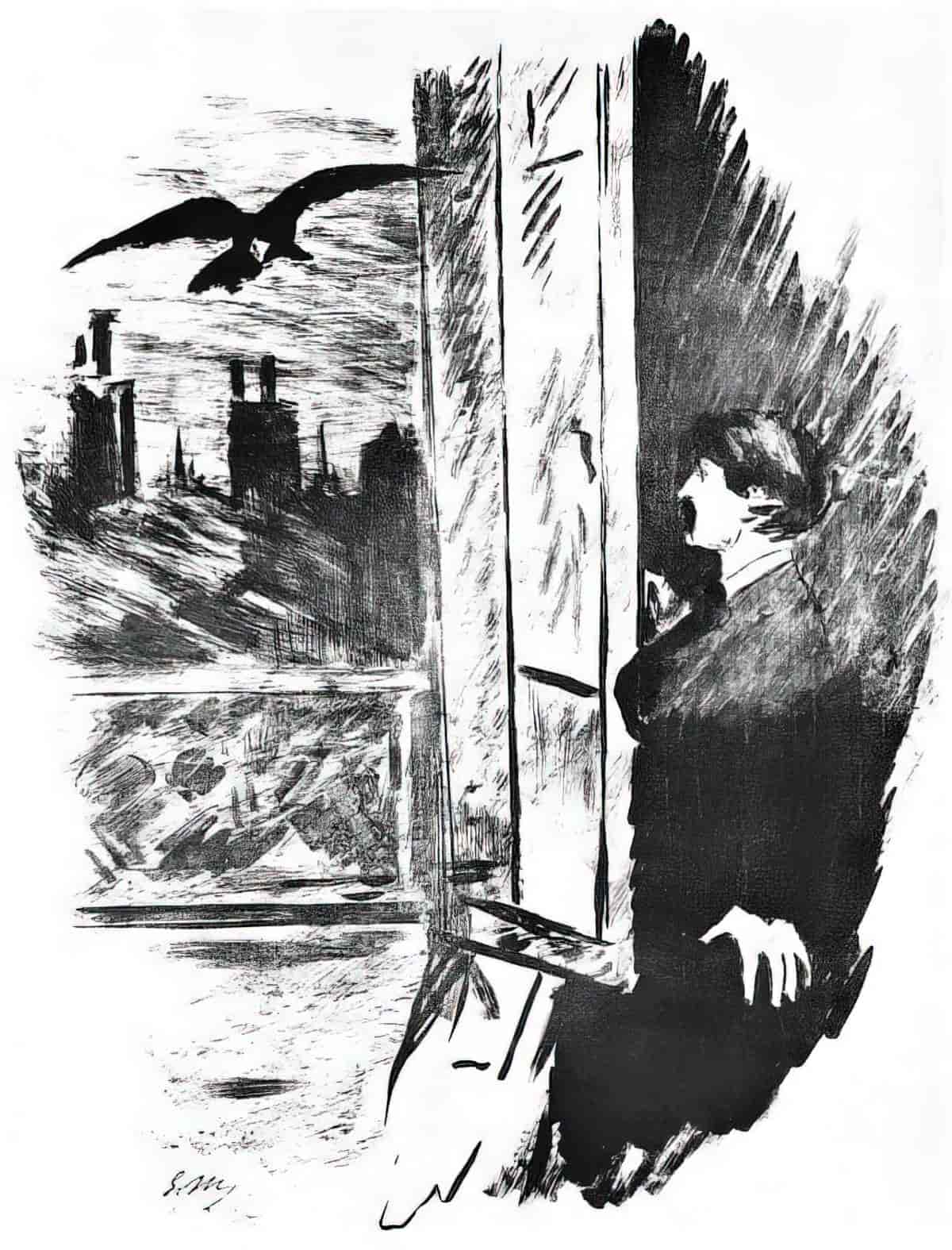

“Surely,” said I, “surely that is something at my window lattice;

Let me see, then, what thereat is, and this mystery explore—

Let my heart be still a moment and this mystery explore;—

’Tis the wind and nothing more!”Open here I flung the shutter, when, with many a flirt and flutter,

In there stepped a stately Raven of the saintly days of yore;

Not the least obeisance made he; not a minute stopped or stayed he;

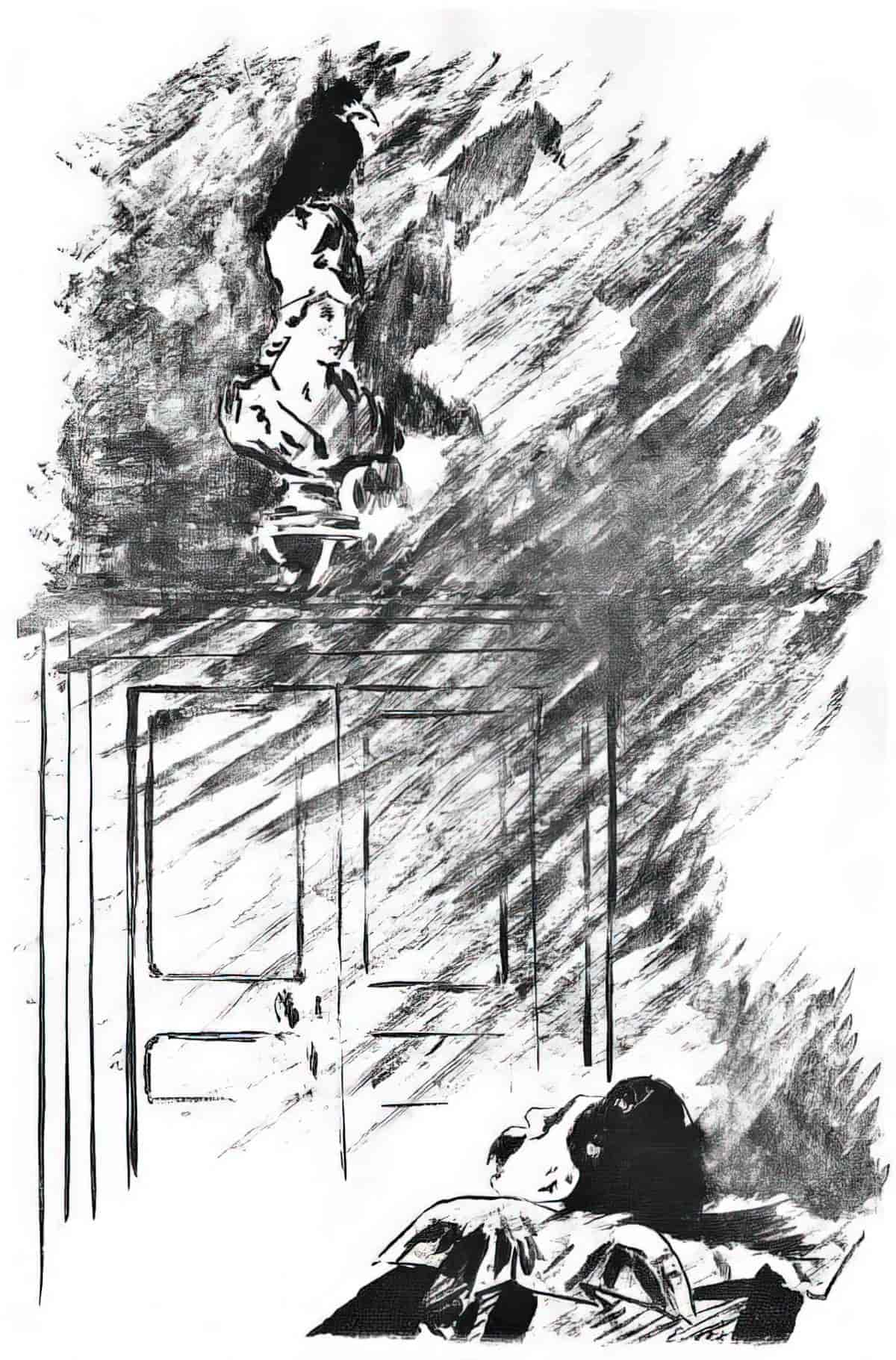

But, with mien of lord or lady, perched above my chamber door—

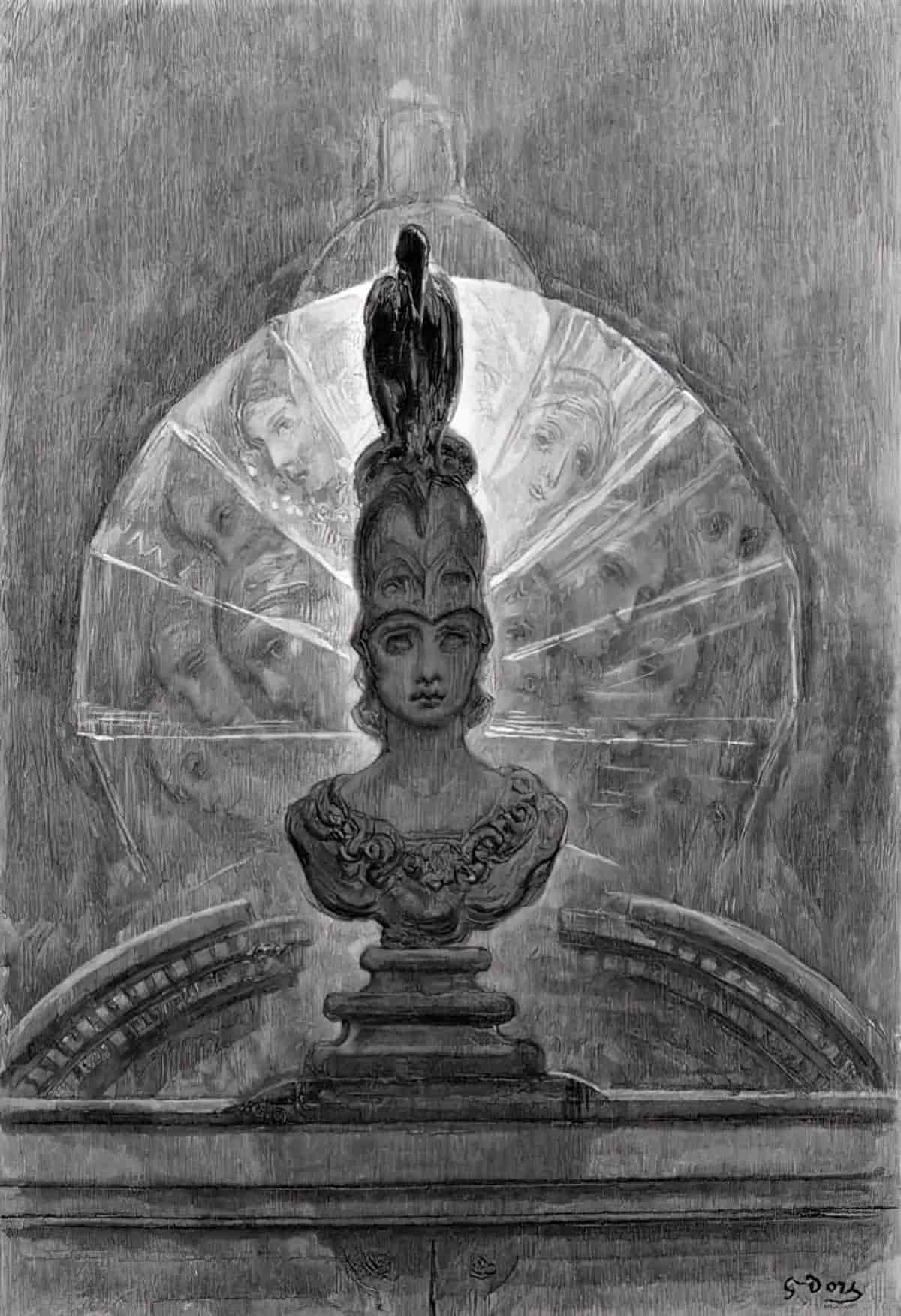

Perched upon a bust of Pallas just above my chamber door—

Perched, and sat, and nothing more.Then this ebony bird beguiling my sad fancy into smiling,

By the grave and stern decorum of the countenance it wore,

“Though thy crest be shorn and shaven, thou,” I said, “art sure no craven,

Ghastly grim and ancient Raven wandering from the Nightly shore—

Tell me what thy lordly name is on the Night’s Plutonian shore!”

Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.”Much I marvelled this ungainly fowl to hear discourse so plainly,

Though its answer little meaning—little relevancy bore;

For we cannot help agreeing that no living human being

Ever yet was blessed with seeing bird above his chamber door—

Bird or beast upon the sculptured bust above his chamber door,

With such name as “Nevermore.”But the Raven, sitting lonely on the placid bust, spoke only

That one word, as if his soul in that one word he did outpour.

Nothing farther then he uttered—not a feather then he fluttered—

Till I scarcely more than muttered “Other friends have flown before—

On the morrow he will leave me, as my Hopes have flown before.”

Then the bird said “Nevermore.”Startled at the stillness broken by reply so aptly spoken,

“Doubtless,” said I, “what it utters is its only stock and store

Caught from some unhappy master whom unmerciful Disaster

Followed fast and followed faster till his songs one burden bore—

Till the dirges of his Hope that melancholy burden bore

Of ‘Never—nevermore’.”But the Raven still beguiling all my fancy into smiling,

Straight I wheeled a cushioned seat in front of bird, and bust and door;

Then, upon the velvet sinking, I betook myself to linking

Fancy unto fancy, thinking what this ominous bird of yore—

What this grim, ungainly, ghastly, gaunt, and ominous bird of yore

Meant in croaking “Nevermore.”This I sat engaged in guessing, but no syllable expressing

To the fowl whose fiery eyes now burned into my bosom’s core;

This and more I sat divining, with my head at ease reclining

On the cushion’s velvet lining that the lamp-light gloated o’er

But whose velvet-violet lining with the lamp-light gloating o’er,

She shall press, ah, nevermore!Then, methought, the air grew denser, perfumed from an unseen censer

Swung by Seraphim whose foot-falls tinkled on the tufted floor.

“Wretch,” I cried, “thy God hath lent thee—by these angels he hath sent thee

Respite—respite and nepenthe from thy memories of Lenore;

Quaff, oh quaff this kind nepenthe and forget this lost Lenore!”

Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.”“Prophet!” said I, “thing of evil!—prophet still, if bird or devil!—

Whether Tempter sent, or whether tempest tossed thee here ashore,

Desolate yet all undaunted, on this desert land enchanted—

On this home by Horror haunted—tell me truly, I implore—

Is there—is there balm in Gilead?—tell me—tell me, I implore!”

Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.”“Prophet!” said I, “thing of evil!—prophet still, if bird or devil!

By that Heaven that bends above us—by that God we both adore—

Tell this soul with sorrow laden if, within the distant Aidenn,

It shall clasp a sainted maiden whom the angels name Lenore—

Clasp a rare and radiant maiden whom the angels name Lenore.”

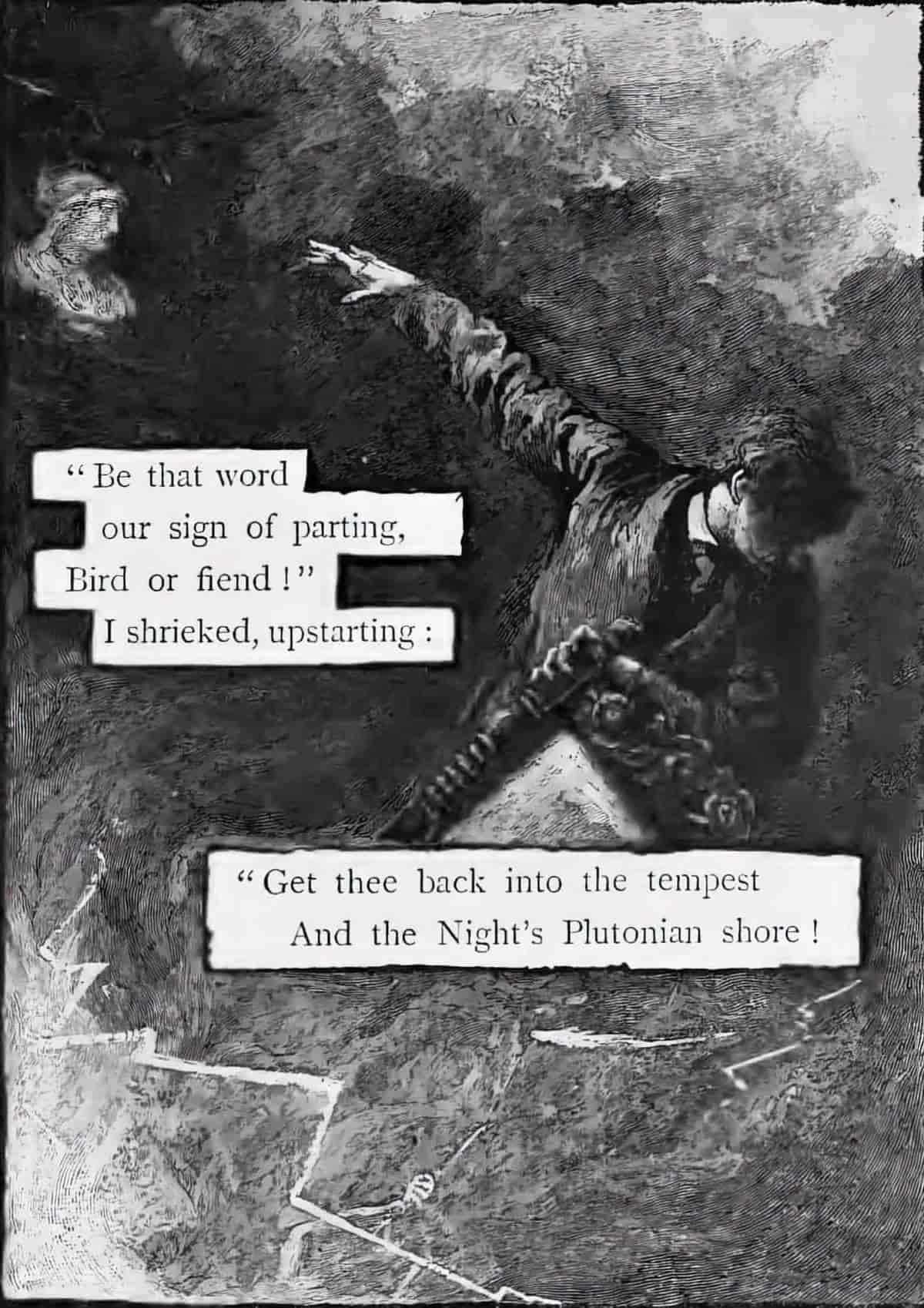

Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.”“Be that word our sign of parting, bird or fiend!” I shrieked, upstarting—

“Get thee back into the tempest and the Night’s Plutonian shore!

Leave no black plume as a token of that lie thy soul hath spoken!

Leave my loneliness unbroken!—quit the bust above my door!

Take thy beak from out my heart, and take thy form from off my door!”

Quoth the Raven “Nevermore.”And the Raven, never flitting, still is sitting, still is sitting

Edgar Allan Poe, first published in 1845, The Raven and Other Poems

On the pallid bust of Pallas just above my chamber door;

And his eyes have all the seeming of a demon’s that is dreaming,

And the lamp-light o’er him streaming throws his shadow on the floor;

And my soul from out that shadow that lies floating on the floor

Shall be lifted—nevermore!

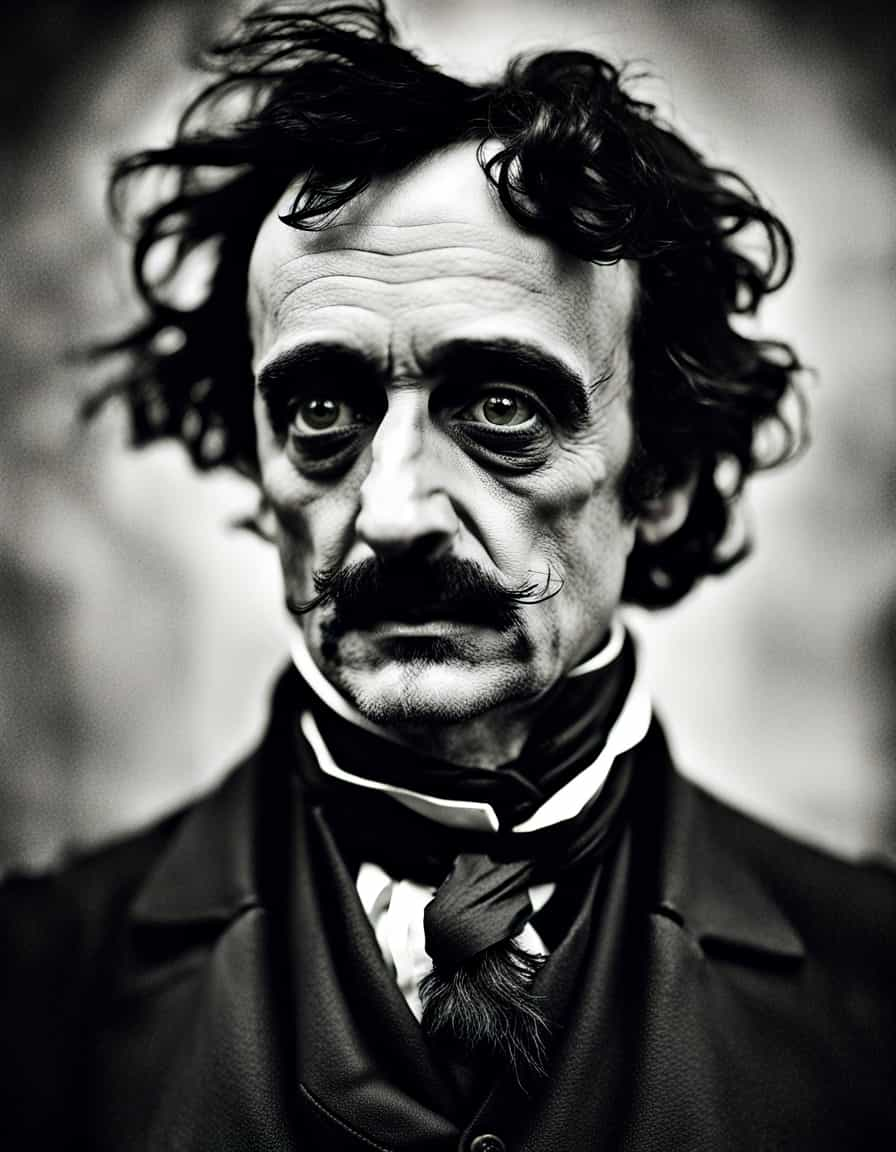

INTERESTING FACTS ABOUT EDGAR ALLAN POE

Edgar Allan Poe was an American writer, poet, and literary critic in the early 19th century. He is best known for his tales of mystery and the macabre. Aside from “The Raven”, he’s well-known for “The Tell-Tale Heart,” and “The Fall of the House of Usher.”

Poe’s works have had a huge impact on literature, especially in the genres of speculative and detective fiction. A TV series based on “The Fall of the House of Usher” was released by Netflix in 2023.

He died under mysterious circumstances in 1849 at the age of 40.

- After Poe was discharged from the army, he met a seven-year-old cousin, Virginia, who would later become his wife. Poe moved in with Virginia’s family (his relatives) but wasn’t actually interested in the 7-year-old. He fell for the woman who lived next door. (Mary Devereaux.)

- This household arrangement ended with Virginia’s grandmother, Elizabeth, died. The family now had no income. They’d previously been living on the grandmother’s pension, as the grandfather had been a General.

- When he was 27 and Virginia was 13, Poe married her. Another cousin was heavily against it, and told Edgar he should wait before marrying a 13-year-old but Edgar got angry and emotional and married her anyway, insisting a 13-year-old is old enough to make up her own mind.

- Poe moved from Baltimore to Virginia to work at the Southern Literary Messenger.

- Some biographers don’t believe Virginia’s and Edgar’s was a sexual-romantic relationship but that it was instead platonic.

- Virginia died of tuberculosis age 24. She’d contracted it five years earlier.

- Virginia believed/knew Poe had been having affairs with other women, one of them Elizabeth F. Ellet. She blamed Ellet for killing her. (Women are blamed for everything, I guess. It’s easier than blaming Poe himself.)

- Poe was distraught by Virginia’s death and turned to alcohol. He started writing quite a bit about dying young women. Leonore in “The Raven” is one example.

- No one took any photos of Virginia. The only image we have is a watercolour painted several hours after she’d already died.

EDGAR ALLAN POE AT THE MOVIES

- “The Raven” (1935) starring Boris Karloff as Poe

- “The Black Cat” (1934) starring Bela Lugosi and Boris Karloff

- “The Fall of the House of Usher” (1928) directed by Jean Epstein

- “The Tell-Tale Heart” (1953) directed by Jules Dassin

- “The Raven” (1963) starring Vincent Price as Poe

- “The Oblong Box” (1969) starring Vincent Price and Christopher Lee

- “The Masque of the Red Death” (1964) also starring Vincent Price

- “The Raven” (2012) starring John Cusack as Poe

- “The Raven” (2020) a French movie, with Jean-Luc Vincent as Poe.

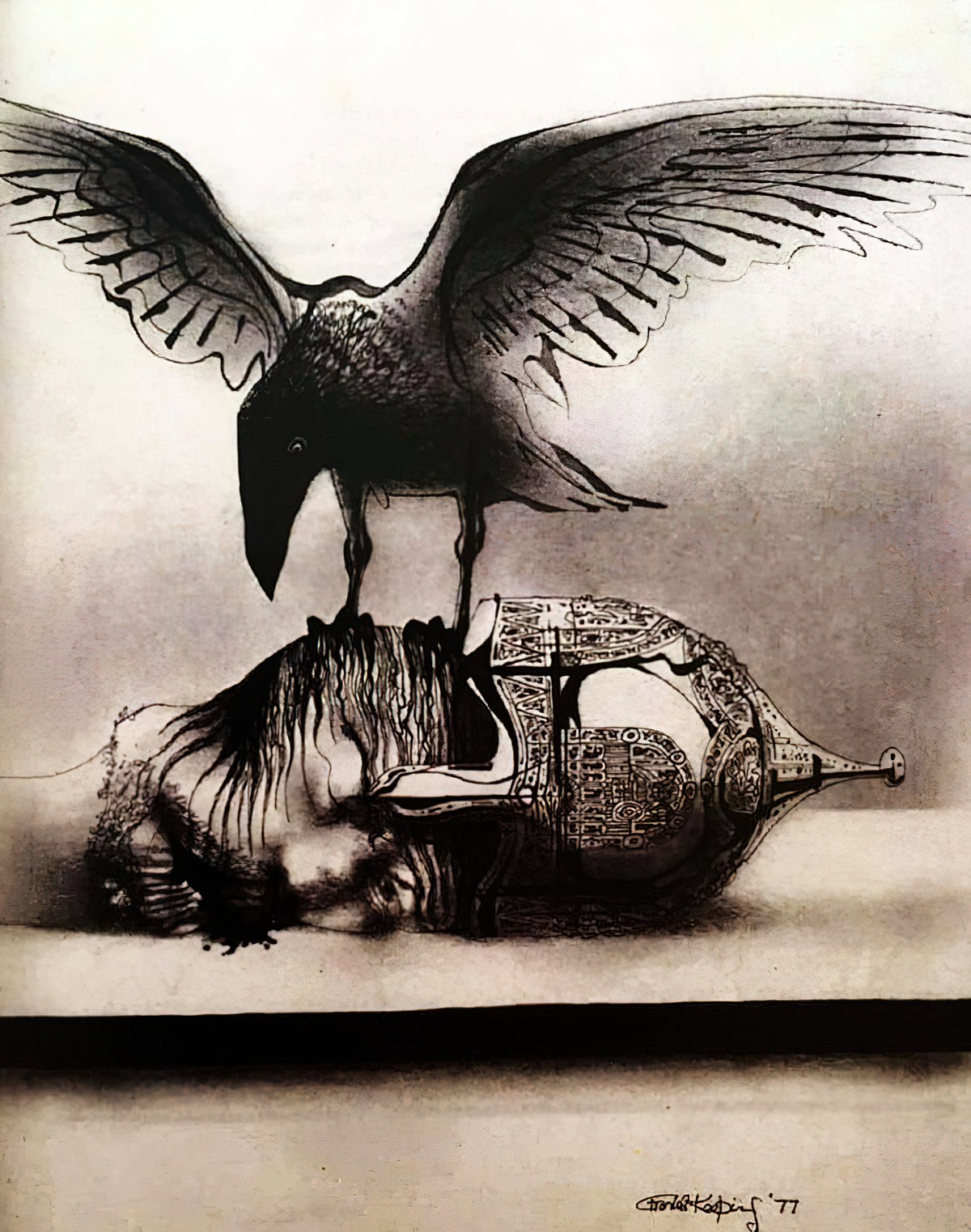

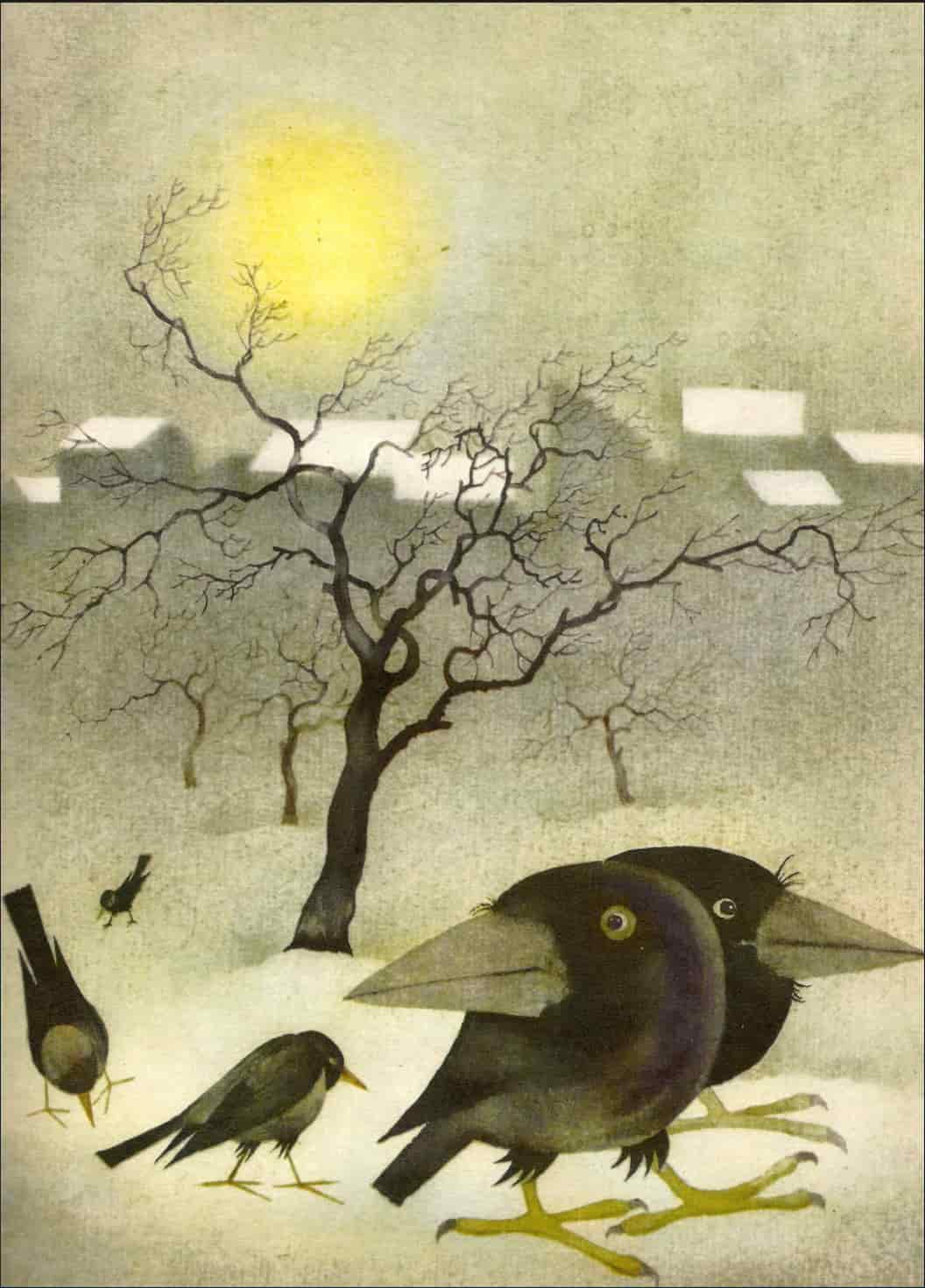

VARIOUS OTHER RAVENS IN ART AND ILLUSTRATION

MORE FAMOUS TALES FEATURING RAVENS

“Gerda and the Ravens“: This is a Scandinavian fairy tale about a girl named Gerda who goes on a journey to save her brother, who has been taken by the Snow Queen. Along the way, she meets a group of friendly ravens who help her on her quest. It is quite similar to “The Snow Queen” by Hans Christian Andersen.

“The Seven Ravens“: In this fairy tale a family has seven sons. One day, their father is angered by their disobedience. He curses them, and they turn into ravens. It is up to their youngest sister, a baby at the time, to grow up, find them in the woods and turn them back into men.

DIFFERENCES BETWEEN RAVENS AND CROWS

These differences impact the symbolism surrounding them, which is similar but a little different.

Size

Ravens are larger than crows. Common ravens (Corvus corax) typically have a wingspan of about 3.6 to 4 feet (1.1 to 1.3 meters) and can weigh 2 to 4 pounds (0.9 to 1.8 kilograms), while American crows (Corvus brachyrhynchos) have a wingspan of about 2.6 feet (0.8 meters) and weigh around 1 pound (0.45 kilograms).

Appearance

Ravens have larger bills and a wedge-shaped tail. Ravens tend to have shaggy, hackle-like feathers on their throats, known as “ruff” feathers.

Crows have smoother, sleeker plumage.

Vocalizations

Both crows and ravens are known for their intelligence and complex vocalizations. Ravens produce a deeper, hoarser croak or “kronk” sound, while crows make a cawing noise.

The vocalizations of ravens are often described as more guttural and varied than those of crows.

Behavior

Ravens are often associated with more solitary behaviour or smaller family groups, whereas crows are more social and tend to form larger flocks.

Ravens are also known for their playful behaviour, including aerial acrobatics and games.

Range

The range of ravens and crows can overlap, but the distribution may vary. Common ravens are often found in more remote or wilderness areas, while crows are more adaptable to urban and suburban environments.

Diet

Both crows and ravens are omnivorous scavengers, but ravens are known for their ability to take down larger prey, such as small mammals and even young birds. Crows are more likely to feed on carrion and smaller items.

Flight

Ravens tend to have slower, more deliberate flight patterns, while crows are often more agile and may perform aerial acrobatics.

To allow gamekeepers to kill crows and jackdaws to “protect” pheasants and partridges, the pheasants and partridges are classed as livestock. But you aren’t allowed to shoot livestock for sport, so when pheasants and partridges are being shot, they’re classed as wildlife.

But you aren’t allowed to round up wild animals at the end of the shooting season, and trap them in enclosures, so when the survivors are being rounded up, they become livestock again.

But if a pheasant flies into a car during the roundup, and causes a crash, you’re not legally liable, because, for this purpose, it becomes wildlife again.

But if it survives the crash and you use it to breed more pheasants, it becomes livestock again, enabling you to claim tax breaks and subsidies. It makes you wonder who wrote these laws ….

Actually, we know who wrote (or passed) these laws: MPs and lords who own shooting estates. They created a fantastically tortuous legal system to enable this unspeakable “sport” to continue, regardless of the havoc it wreaks and the ecological damage it inflicts.

For people with this mindset, the animal kingdom is divided into two categories. Game, which you pay to kill. Vermin, which you pay other people to kill.

The pheasant is a non-native bird that belongs to the same family as chickens and turkeys (Phasianidae). Imagine the outcry if farmers bred 47 million chickens every year to be released, then forced to fly over a line of people with shotguns, to be blasted out of the air.

Why do we see this any differently? Why are people allowed to kill and wound livestock for pleasure? Why are they allowed to release a greater weight of birds into the countryside every year than all the native birds in the UK put together?

Why are these omnivorous birds allowed to devastate our wildlife, clearing woods and fields of insects, lizards, baby snakes, seeds and anything else they can find? Why are their owners allowed to kill a vast range of wildlife to protect this unfenced livestock?

Every aspect of this practice is an outrage. It reflects the continued domination of a landed elite, whose power is such that they can craft the law to suit themselves, however labyrinthine it has to be. Is this country a democracy, or a semi-feudal barony?

It’s a gigantic, state-sanctioned cosplay, simultaneously deadly serious and utterly risible.

@GeorgeMonbiot 6:08 PM · Jan 4, 2022