What is the overview effect?

The sense of awe and connectedness astronauts feel as they gaze back at earth from outer space. The overview effect is a type of cognitive shift.

If people sat outside and looked at the stars each night, I bet they’d live a lot differently. When you look into infinity, you realize there are more important things than what people do all day.

Bill Watterson (Calvin & Hobbes)

Similar Concept: Oceanic Feeling

“Oceanic feeling” is a psychological term coined by Nobel Prize laureate and French writer Romain Rolland. He described “a sensation of ‘eternity’”, a feeling of “being one with the external world as a whole”.

New Zealand singer/songwriter took this concept and turned it into a song.

Who came up with the concept?

The writer Frank White, who since the 1980s has been interested in finding out from astronauts if they had experienced any shift in mindset, epiphany or self-revelation after seeing the Earth from the distance of space.

What did the astronauts say?

Astronauts reported feelings wonder, awe and transcendence:

“You start to see the world as what it actually is. It’s one place. We, collectively, are likely to make good decisions for ourselves and where we live when we see Earth as one place where we all live. “Holy moly. There’s not a single thing on earth that’s alive or been alive that isn’t connected to something else, in some way.”

THE OVERVIEW EFFECT IN FICTION

If you’re reading a picture book and you ever come across a page like this one, you might be seeing the overview effect as utilised by storytellers:

Philosophers use the word ‘sublime’ to describe this feeling of becoming one with something bigger as ‘sublime’. The scene with the Overview Effect tends to happen near the end, as the character experiences Anagnorisis. Quite often they are sitting someplace high, like a mountain or a roof.

I’ve noticed the Overview Effect utilised in all kinds of stories as I analyse narrative for this blog. In literature, it comes in various forms. Authors tend to use it in a similar way across a corpus of work.

PICTURE BOOK EXAMPLES

- We Found A Hat by Jon Klassen. Two tortoises find a single hat and work out how they are going to deal with this and remain friends. Klassen ends this story by having the turtles imaginatively venture high into the sky. They realise that in the scheme of things, the tiff over the stupid hat isn’t that important after all, and certainly not important compared to their friendship.

- Mr Rabbit and the Lovely Present by Zolotow and Sendak. The writers of cumulative plot shapes have the challenge of creating some kind of building tension, and then creating a sense of ending for the reader. This carnivalesque, cumulative picture book is a good example of how storytellers can achieve both of those things by having characters look up into the sky and contemplate the stars for a moment.

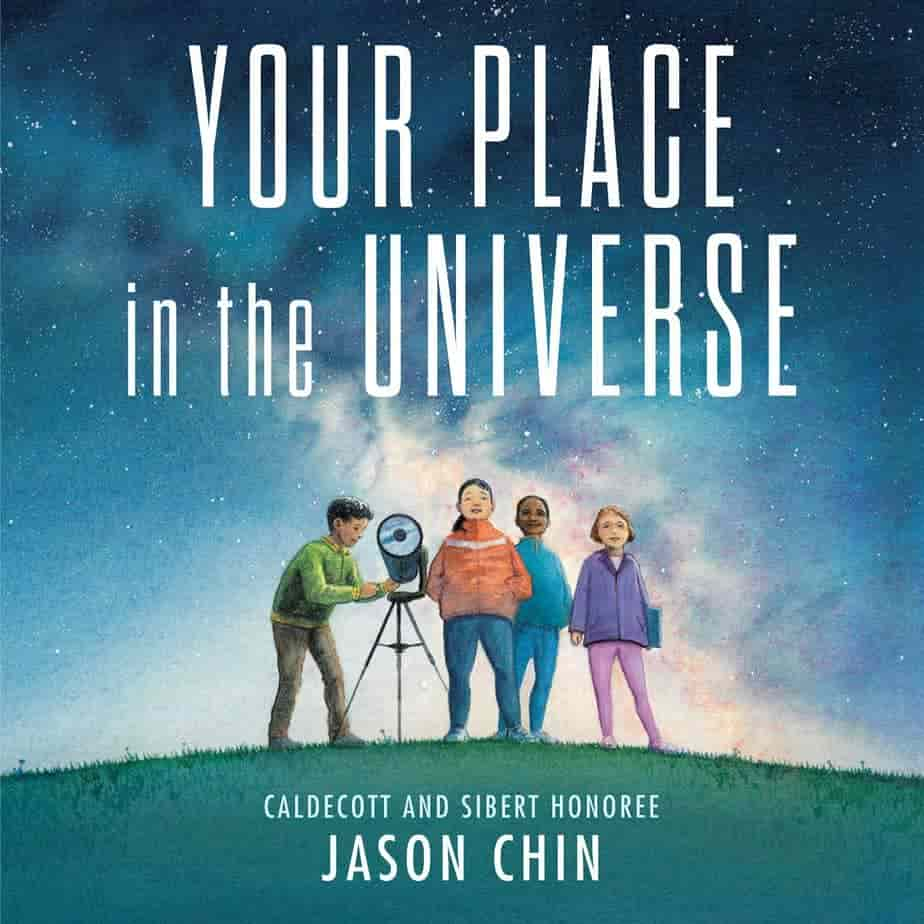

Your Place in the Universe introduces readers to the mind-boggling scale of the known Universe.

Most eight-year-olds are about five times as tall as this book… but only half as tall as an ostrich, which is half as tall as a giraffe… twenty times smaller than a California Redwood! How do they compare to the tallest buildings? To Mt. Everest? To stars, galaxy clusters, and . . . the universe?

MIDDLE GRADE

- When You Reach Me by Rebecca Stead is a good example of an adolescent looking up at the sky and realising they are a part of something bigger, a development stage typical of adolescents, who are starting to move out of the home and forging their own way in the world.

When Georgia finds a secret sketch her late father—a famed artist—left behind, the discovery leads her down a path that may reshape everything holding her family and friends together.

Georgia Rosenbloom’s father was a famous artist. His most-well-known paintings were a series of asterisms—patterns of stars—that he created. One represented a bird; one, himself; and one, Georgia’s mother. There was supposed to be a fourth, but Georgia’s father died before he could paint it. Georgia’s mother and Georgia’s best friend, Theo, are certain that the last asterism would’ve been of Georgia, but Georgia isn’t so sure. She isn’t sure about anything anymore—including whether Theo is still her best friend.

Then Georgia finds a sketch her father made of her. One with pencil points marked on the back—just like those in the asterism paintings. Could this finally be the proof that the last painting would have been of her? Georgia’s quest to prove her theory takes her around her Upper West Side neighborhood in New York City and to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which was almost a second home to Georgia, since she had visited favorite artists and paintings there constantly with her father. But the sketch leads right back to where she’s always belonged—with the people who love her, no matter what.

The only thing Rosalind Ling Geraghty loves more than watching NASA launches with her dad is building rockets with him. When he dies unexpectedly, all Ro has left of him is an unfinished model rocket they had been working on together.

Benjamin Burns doesn’t like science, but he can’t get enough of Spacebound, a popular comic book series. When he finds a sketch that suggests that his dad created the comics, he’s thrilled. Too bad his dad walked out years ago, and Benji has no way to contact him.

Though Ro and Benji were only supposed to be science class partners, the pair become unlikely friends: Benji helps Ro finish her rocket, and Ro figures out a way to reunite Benji and his dad. But Benji hesitates, which infuriates Ro. Doesn’t he realize how much Ro wishes she could be in his place?

As the two face bullying, grief, and their own differences, Benji and Ro must try to piece together clues to some of the biggest questions in the universe.

SHORT STORY EXAMPLES

The Overview Effect is sometimes achieved by creating various generations of a family (or community) and then telescoping them by playing around with time. Annie Proulx often creates three generations of characters in her short stories even when she’s telling the story of a single character. This creates an Overview Effect by showing the reader the landscape and earth is much bigger than any individual, and also miniaturises the individual by making their life seem short, and the landscape seem bigger.

Alice Munro also juxtaposes young against older women. Sometimes this takes the form of an older woman looking back at decisions made by her younger self. Sometimes (even within the same story) a younger women meets an older woman when she is young, and the story is told by the younger woman’s older self. By meeting an older woman as a young person, it’s almost as if she met her older self. Alice Munro does all sorts of interesting things with time, and her short stories are regularly described as novelistic. Although both Proulx and Munro use cross-generational stories to create an Overview Effect, each of these writers does it quite differently.

Modernist writer Katherine Mansfield created a kind of Overview Effect in her most famous trilogy by juxtaposing Kezia against her mother, auntie and grandmother, who all live in the same house.

- “Prelude” by Katherine Mansfield. The symbolism around the aloe (the story’s original name) emphasises the family’s link to the past.

- “Deep Holes” by Alice Munro. Munro creates an Overview Effect by Alice Munro turning Sally into a tiny figure within a vast landscape. We are seeing her from above, almost as if from the stratosphere. We are no longer involved in her life. This is how we leave her.

- “Dance In America” by Laurie Moore. A character looks up at the sky and sees a Turkish Flag, subverting any sublime feeling characters often feel in more typical, romantic stories.

- “The Fifth Story” by Clarice Lispector. Lispector achieves the Overview Effect (a cognitive shift in awareness) by referring to an event from the distant past — the erupting of Vesuvius. Space doesn’t have to be involved. A volcano works, because it’s much, much bigger than us, and we can’t possibly control it.

- “Dump Junk” by Annie Proulx. Proulx creates a brief Overview Effect by taking us up into the cosmos, showing us that the character Bobcat has unwittingly wished evil upon his grandsons.

THE OVERVIEW EFFECT IN HORROR

Perhaps you’re noticing that The Overview Effect functions as a bit of a cosmic horror trope. In cosmic horror, the message is always something like: The villain is unknowable, and therefore super scary. In classic cosmic horror, human viewpoint characters often lose their minds or die at the end.

Another useful concept when talking about horror is ‘spatial’ or ‘disorientation’ horror. There are many ways of making an audience feel uncomfortable in their seats. Creating an Overview Effect can make audiences feel small and untethered, and is thereby useful to storytellers working in the horror subgenres.

That’s why you’ll quite often find The Overview Effect as a story ending. Moving now to the realm of picture books, this is how Jon Klassen wraps up “We Found A Hat“. But this time the viewer stays on the ground, looking up at the characters rather than looking down. These tortoises have both acted morally after making a very tough moral decision (to share a single hat between them), and with this view from the ground, they now seem almost angelic. However, the small size of them against the backdrop of a huge sky nonetheless works to create an Overview Effect.

More than three decades ago, Frank White coined the term “Overview Effect” to describe the cognitive shift that results when viewing the Earth from space and in space, from orbit or on a lunar mission. He found that this experience profoundly affects space travelers’ worldviews—their perceptions of themselves, our planet, and our understanding of the future. White notes that astronauts know from direct experience what the rest of us know intellectually: we live on a planet that is a natural spaceship moving through the universe at a high rate of speed. We are, in fact, the crew of “Spaceship Earth,” as Buckminster Fuller described our world. All of us are, in a very real sense, astronauts, exploring the cosmos every day, even though we don’t always see it that way!

BE WARY OF CORPORATIONS CO-OPTING THIS CONCEPT

Australia’s Schwartz Media produces a podcast called 7am. Ceridwen Dovey warns us of how “The Overview Effect” has been repurposed by rich people hoping to convince the rest of us they’re doing something wonderful for humankind.

The early era of space exploration was dominated by romantic ideas of universal connectedness. But the increasingly privatised nature of the space industry has obscured that vision. Today, Ceridwen Dovey on the new space industry entrepreneurs, and why we should be worried about what they’re planning.

“The Colonisation of Space“

NOTES FROM THE PODCAST

As the space industry grows, romantic ideas about our connectedness is the story we’re told back on earth, while corporoations colonise space the same way people with many resources have colonised Earth.

These beautiful sentiments have become co-opted. Doing something for humankind is now a moral justification for anything done in space. The concept of the Overview Effect is now being used to justify profiteering, serving different interests. The concept was formerly used by peace activists and is now used by corporations.

This is literally happening in the dark. Much of it is classified information because it is in a militarised zone.

It used to be the case that about a third of activities in space were military, another third were national governments and a third were commercial activities. Come 2021, commercial activities have now overtaken the other activities in space. Earth now has a ‘space economy’. The details of this are notreported in the mainstream news, so most of us are unaware of what’s happening in space.

Rich white men are building space empires for their own profit:

- Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic is trying to start space tourism.

- Space X is well-known, but how many people know what they’re up to?

- Amazon has Blue Origin. As of 2016, Blue Origin was spending US$1 billion a year, funded by Jeff Bezos’ sales of Amazon stock.

- World View Enterprises is the most clear example of a corporation taking the Overview Concept and incorporating it into their very name. Their satellites offer a surprisingly detailed level of surveillance. Ostensibly they can tell if someone is holding a gun. In reality, gas and oil companies are very interested in this technology.

Richard Branson says things like, “Together we can make space accessible in a way that’s only been dreamt of before now. By doing that we can truly bring positive change to life on earth.” But Branson’s customers are the uber-wealthy. Using this kind of language, he creates the illusion that he is generously colonising space for all of us.

We need to be cautious and critical in the face of utopian tech-speak, especially when it comes to something as inherently wondrous as outer space.

Once we allow rich people to make profit from mining the moon etc. it will be difficult to go back. America has already given its own citizens the right to mine, own and well space resources, against international law.

This is not the concern of future generations. We are currently on the precipice of huge change. These corporations are not in space for ‘science’. They are in space for themselves. Let’s learn from the mistakes of earlier generations who broke frontiers they should not have, right here on Earth.

Header painting: New Mexico cloudscape illustrated by Eric Sloane (1905-1985) for the booklet ‘Celebrating the National Air and Space Museum Smithsonian Institution’, 1976.

FURTHER READING

Finding Awe Amid Everyday Splendor: A new field of psychology has begun to quantify an age-old intuition: Feeling awe is good for us. BY HENRY WISMAYER