If you head down to your local shopping precinct on a Saturday you might catch sight of a boy slouching in an alleyway – that shadowy gap between the bookstore and where your mum buys her skirts. The boy might be on the scrawny side but he’s older than he looks. That’s why bouncers won’t let Benny Bonedigger into bars.

“You can’t be eighteen, son. Come on, give your big brother back his purse or I’ll call the coppers.”

So Benny buys himself a burger for his second dinner, hoping to bulk up. If you keep an eye on him, you’ll see him pluck out the gherkin with those white-knuckled middle-class fingers of his. He’ll fling the pickle against a shop window. Watch the gherkin slide down the glass. It leaves a slimy snail-trail in its wake. Tomorrow morning, a middle-aged retail assistant will wipe her shop-front clean with a fresh paper towel, a hand-gun of bubbly-blue and much clicking of the tongue.

Benny Bonedigger grins at the thought of it.

Benny’s life lacks excitement. Teachers say he’s “away with the faeries” most lessons. He gets sidelined at football for cussing at the ref. His father won’t let him on the internet after dinner.

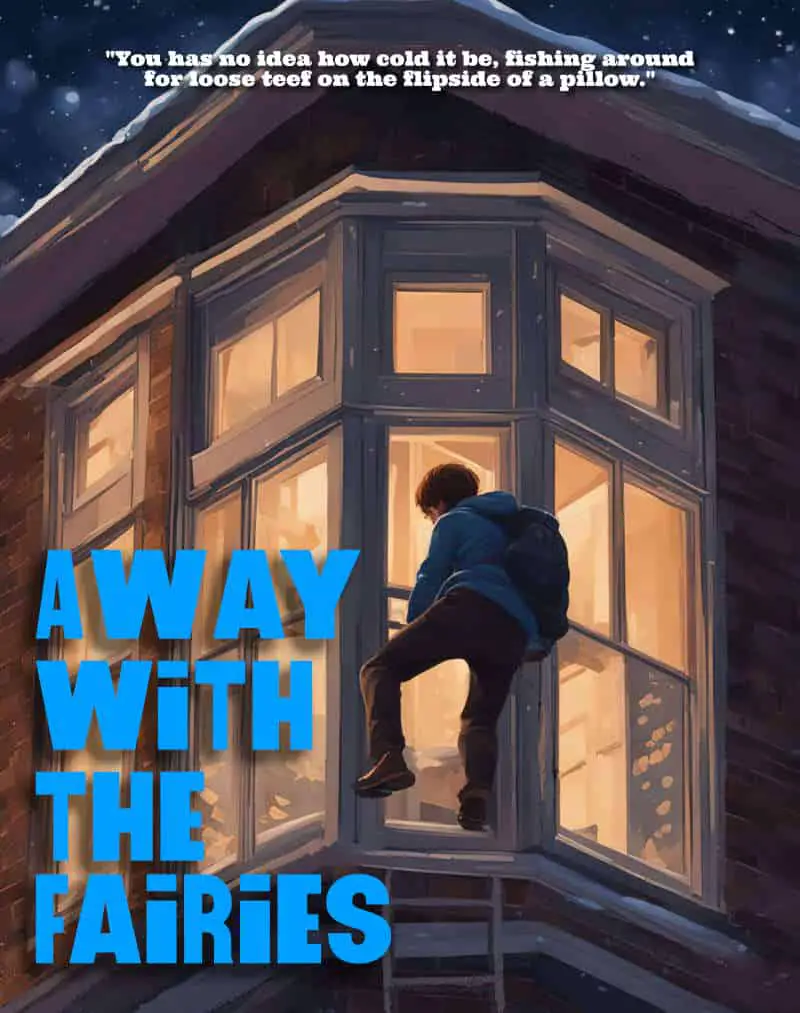

So this is how Benny finds his fun, each Saturday evening after his bangers and mash. He waits until his parents settle in front of the movie on ITV4, makes out he’s got to write a paper on The Black Death, then escapes from his second-storey window. Benny negotiates his way down the fire escape. He’s careful how he goes. Benny might be a mischief-maker but he doesn’t want to get himself killed: not by falling off a rickety ladder. And not by getting the bash, either, though that would accrue more glory.

That’s why Benny picks on kids his own size, preferably smaller. This narrows down his options. Twelve-year-olds are good. They get about in gaggles of ten, but there’s no safety in numbers. These kids make mischief by hurling sugar babies at taxis, or scrawling tags on street-signs with markers nicked off a teacher. They stuff empty crisp packets between the slats of those wooden benches in the open mall. But don’t be fooled. The dark hoods conceal frightened eyes. Long cuffs conceal flimsy hands. These kids are scared and shouldn’t, by rights, be out after dark. They’re not about to argue with a boy who goes by the name of Benny Bonedigger.

An ominous tune – heavy on the skewed guitar and synthesised heart-beats – plays through Benny’s mind. The soundtrack builds as he approaches his target.

“Hey girlie-boy, spare me some cash?”

Benny has his act down pat: a faux-friendly request reinforced by a switch-blade held low.

The kid shakes its head. The mates scarper.

“You sure about that? I think you can spare me a tenner.”

Benny imagines himself the lead actor of a gangster flick. The darkness of winter, with its low, city smog, paints an authentic landscape in grainy black and white. Benny’s mugging gear consists of ripped jeans, a woollen hat and his school overcoat. But he imagines himself three feet taller, all decked out like a gangster: tailored suit, cufflinks, chunky watch, the lot.

“Thank-you very much,” Benny says, swiping the cash. “Hmmm. Let me relieve you of that mobile.” Benny shows his teeth. The knife glints under a street-lamp. “Dry your eyes, mate. Daddy will buy you a later model.”

The music climaxes in Benny’s head. The synthesised heartbeat ceases. An owl hoots; scared footsteps fade to silence as the victim runs off-screen. The illusory eye of a bird’s eye camera follows Benny as he saunters away with his prize.

Benny is wearing a pair of second-hand trainers. The kid’s brighty-whities pinch a bit around his big toe, but muggers can’t be choosers.

Benny returns to the shadows of that alleyway. His own heart rate is steady. These kids are too easy. He’s ready for a bigger challenge.

You may have noticed the old fellow in the long overcoat: the one with the emphysemic cough and yellow stumps for teeth. Nobody knows where he’s going. Nobody knows where he’s been. Like Benny, this old man hangs about the shopping precinct of an evening. He peeps around corners, skulks about in shadow, avoids the light of the moon. He keeps his one good eye glued to the footpath, swooping with surprising agility upon any loose change. He sometimes mutters sweet nothings into the sleeve of his anorak before dashing off with apparent urgency.

Strangely, this old man carries a briefcase: an incongruous fashion-statement of Italian calf-skin leather. Most passersby do not dwell on the inconsistency; they assume the old boy nicked the case off a businessman commuting into The City, and good on him. But the expensive briefcase intrigues Benny. In movies, cases like this contain three rows of cash. Well, now. Benny must find out.

Another film score builds inside his head. He readjusts imaginary cuff-links and checks an imaginary watch.

He approaches the old fellow from behind, waiting until he bends double to retrieve 20p, planted earlier. Benny grasps the briefcase with two firm hands. The old man is more wily than he looks. They each grunt and gasp. Eventually, Benny stumbles backwards into shrubbery. The old man snarls and spits, for his mugger holds the loot. There is a short chase down the shopping precinct but Benny, in the prime of his youth, scales an industrial wall. He jumps with a thud onto a grocer’s skip and disappears into a camouflage of cabbage leaves and rotten spuds.

The old man clutches at his chest, panting heavily. Venous hands clasp knobbly knees.

Benny Bonedigger waits among the vegetables, sleeve to nose. Confident the old man has gone, he makes his way back to his semi-detached, grinning like a kiddie with a Santa sack. He sees shady characters waiting for him behind every bush. That’s adrenaline for you. He shinnies back up the fire escape, jimmies open his bedroom window and flops onto his bed. The house is silent but for rhythmic breathing from his parents’ bedroom and the odd clink from the central heating.

Moonlight peeps through the curtains, casting his bedroom in blue. Benny’s own pale eyes are made for the night-time; he opens the briefcase with trembling fingers and looks inside. He dare not breathe.

But someone has already relieved the old man of his cash. Instead, Benny finds a simple drawstring bag made of glimmering, velvety material. *Emeralds and rubies*. The old man is a jewel thief, no doubt.

His cold thumbs fumble as he opens the bag. The jewels fall like Scrabble letters into his palm. But these are no game pieces, and this is no game.

Benny lurches backwards.

*Teeth*.

Milk teeth, pinched off kiddies.

What kind of sicko gets about with a bag of sixty-three teeth in his briefcase? Benny sits hunched against his bed-head, staring at the ivory jewels scattered across his duvet. He can’t believe he touched those things. Even in dim light, he sees that these are no replicas. These are the real thing. Some of the teeth have pieces of bloodied flesh attached at the root. One of the little molars has something brown and glutinous – toast? – lodged between its cusps. Another appears to glint like a switchblade. Benny pokes it. Sure enough, it winks back. An amalgam filling catches the moonlight.

Oh hell.

Benny loves a thrill, but this is not the kind he was after. Filled with disappointment, he scrapes the teeth back into the drawstring bag, throwing it to the furthest corner of his room.

Who is that old man? Might he be some dental assistant, selling teeth on the black market? Might he be a creepy taxidermist, specialising in authentic replica human heads? No, that’s plain ridiculous.

With instant clarity, Benny knows the answer.

The old man is a mass murderer. He kills his victims then nicks off with their teeth. On the telly, dental records identify a victim. With no teeth, the skinny guy in the anorak will never get caught. Genius. *Madness*. The madman is bound to come after Benny.

Benny’s got the shivers now. He creeps downstairs to check his parents have locked all the doors. He latches his window, good and tight. He thinks of jamming his bookcase against his bedroom door, but it’s heavy and he can’t be bothered shifting all the books. He’ll turn the nightlight on instead, the one in the hallway. He hasn’t needed that since he was fifteen, but he won’t be able to fall asleep without it.

Benny settles down, snuggled deep in his bed. He inhales the familiar scent of his pillow and holds a fluffy bear to his chest. He resists the urge to suck his thumb. (It needs a good wash after fiddling with those teeth.)

It’s hard to say when, but Benny eventually falls asleep: a fitful slumber, interrupted by murderous visions and silent screams.

At ten past four, Benny is woken by scamperings and rustlings. In the movies, the victim always sits bolt upright in bed. But Benny doesn’t move. His eyes are wide-open but his body is the victim of sleep-paralysis. From his lying-down position he can see a thin line of light coming under his bedroom door. Shadowy things flit down the hallway: small figures, otherworldly. Maybe it’s just his mum, up for a pee. He waits for a reassuring hiss of the cistern. He hears nothing.

He forces himself to close his eyes.

When he opens them again, he expects to see the football poster tacked to his ceiling. But no. He sees a wrinkled face – a familiar face – with one good beady eye and yellow stumps for teeth.

“Don’t make a sound,” says the deep, whispery voice. One chilly hand is clapped across Benny’s mouth, but the boy cannot scream if he tries. The creature’s other hand grips a length of peppermint dental tape. Benny smells the mint – the aroma is overpowering. He feels the twine cut across his Adam’s apple.

“Shhh,” says the man-creature, backing away.

Benny sits up in bed, nice and slow. That’s when he notices the other one: the lithe figure by the bookshelf, fingering his CDs. The companion, too, is all scrawn and bone. He wears fatman pants which only serve to emphasise his cavernous abdomen. He wears a football shirt in colours Benny has never seen. Skinny arms emerge from the sleeves; these are the hirsute forearms of a gorilla.

The hairy one is not impressed with Benny’s collection of 80s music. He follows the boy’s gaze.

“You be staring at my luxurious, hairy limbs.” He speaks with a lisp for he’s got no teeth at all. “This thick growth be for reaching under pillows. You has no idea how cold it be, fishing around for loose teef on the flipside of a pillow.”

Now the other one speaks. “Begs your pardon for barging in like this. Let me introduce us-selves. You and me met earlier this evening. And my esteemed boss, well, he needs little by way of introduction.”

Benny isn’t in the mood for forging friendships. “If you’ve come for the case, take it and leave.” He hasn’t got much of a memory for faces. But he’s never seen the hairy one in his life. He would never forget such arms.

The hairy one introduces himself. “I be none other than Al Dente. You can call me Al.”

It may be the shock and disbelief, but Benny looks blank.

“A-K-A ‘The *Toof* Faery’.”

“Yeah, right.” Benny’s false bravado morphs into semi-confidence. There’s no doubt about it; he must be immersed in one very lucid dream. He pinches himself, and it hurts. Maybe he’s dreaming that too. Entirely possible, and a ridiculous experiment. “If you’re The Tooth Faery then who’s your mate? Wee Willy Winky?” Benny slaps his knee at the joke of it all. That hurts too.

His visitors are not amused. “I’m Tony,” the Anorak replies. “Tony The Mouth, Tooth Faery Contractor.” He hands over a business card – it’s ratty at the edges and dirty at the creases. It’s his one and only copy – he reaches for it back.

Benny releases his grip on the card and narrows his eyes. “How come you’re both gummy as a bear? I always thought tooth faeries had teeth.”

“Who told you that tripe? The Easter Bunny, me thinks. S’pose he told you chickens have teef and all.” The Tooth Faery Boss has spied the drawstring bag. He picks it up and fishes around inside. Now he grabs a tooth between his dirty thumb and forefinger. To Benny’s disgust, The Tooth Faery grinds it to dust between his hardy gums. He smacks his lips, as if enjoying a salted peanut at a birthday party.

“Mmm,” the Tooth Faery says, licking his fingers. “I knows how to pick ‘em. Let me be explaining something to you…”

“Benny.”

“All right, Betty. We was much impressed by your thieving this evening. We likes the way you be creeping about of a night. You be good and skinny so’s you can slope all-of-a-stealth round bedroom doors, snagging the loot without no fuss. We followed you home ‘cos we likes how you work. Tony here, he be retiring next month and I been keeping an eye out for a replacement, like.”

The Tooth Faery digs into his bag of tooth lollies and shovels a few more into his gob. Benny winces at the crunch. He’d rather hear fingernails down a chalkboard.

“Good news is, Benny Bonedigger, you be the new recruit.”

“Recruited for what, exactly?”

“Apprentice Tooth Collector. In our culture, the fallen tooths of Yuumin kiddies be delicacies. Just like saffron, only fragrant… Like caviar, only crunchy…. Like truffles, only – ”

“I don’t want to be no stinking contractor for no stinking faery boss.” This is a nightmare. Not a dream. Benny Bonedigger summons up courage by squeezing the leg of his teddy bear.

The Tooth Faery must detect reluctance in Benny’s tone for it’s now that he whips out the headless electric toothbrush. He wears it concealed in his elasticised waistband.

Benny gulps. He doesn’t like the look of that weapon, not one little bit. He wonders if it’s loaded with rechargeable double A’s.

“I do appreciate the job offer,” Benny says. “In fact, I’m rather flattered to be head-hunted like this. But the careers counsellor at school would prefer to see me engaged in something more creative… more – ”

That’s when The Mouth whips out the big pliers. Benny has no idea where they came from. The fellow must keep them on quick draw.

“Okey dokey.” Benny holds up his palms. He nods enthusiastically, which is strange, because ‘enthusiastic’ isn’t really the word for his current predicament. Benny thinks he’d better be keeping his mouth shut from here on in.

So The Tooth Faery continues, occasionally pressing his nail-bitten thumb onto the rubbery button of the electric toothbrush, to show who’s boss.

“You don’t be getting no choice in these matters.” The Tooth Faery hisses through his non-existent teeth. The electric toothbrush vibrates with menace. “No one ever asked *me* if *I* wants to be a Faery, but these things be innate, innit. It be something deep down inside of us, bursting to get out.” *Buzzzz*. “We can’t be helping what tempts us, Benny Bonedigger.”

Benny thinks of interjecting but he is silenced with a buzz.

Tony the Mouth produces a folded piece of A4 paper from the interior pocket of his anorak. He reads without inflection, like he’s been chosen to say thank-you to the guest speaker at a boring assembly.

He clears phlegm from his throat. “Your employment with The Tooth Faery will commence on this day and continue, subject to terms, until you kicks the bucket.” The Mouth coughs again. “I’m paraphrasing, mind.”

“Get on with it,” urges the boss.

“As contractor, you will gather coins what people drop on the streets. You will exchange aforementioned coins for spare teeth what kiddies leave under their pillows of a night. You will be on the hunt at all times, peering about for loose coins and loose tooths. No cash jobs on the side. That means no day-lighting, you hear?”

The Tooth Faery boss reaches for a hip-flask and swigs something potent. “Wishing fountains be the best place for scouting out coins,” he says. “That be an insider tip for you. Giddy up, Mouth.” The Tooth Faery swallows another mouthful with a grimace and offers the concoction to Benny. “Now, be having a swig of me spearmint gargle, to grow some hairs on them nasty, naked arms. They be giving me the creeps, like one of them bald cats.”

Benny Bonedigger swallows reluctantly. He doesn’t like to share drink-bottles; you never know what you might catch. But he gulps it down, glad of the excuse for his watery eyes. “I’m more of a menthol man, myself,” he says.

The Boss pats his back with affection.

Tony The Mouth continues with his ramble, squinting at the page through a monocle. The Tooth Faery snaps his fingers and points to the floor. Benny obeys, gathering up his crumpled clothes, shoving the least rancid of his shirts into a rucksack.

The Mouth winds up his speech and passes Benny a quill, with an inkwell made of pewter. The contract is a series of stick figures, sketched by someone who must’ve skipped art class. Benny makes out a child sleeping, an H for his bed and a rectangle for his pillow. Those manic flourishes must symbolise teeth flying about all over the place – or a leaky quill.

Benny has had his own bank account for a few years now, and has perfected his signature. He dips the quill into silvery ink and wonders whose pillow is missing a feather.

The visitors swig and gargle by the window. They are in no urgent hurry. It has been a slow day for wobbly teeth.

A calm settles over Benny. Nothing matters anymore: not his boring lessons, not his A-levels, not even his career prospects. Benny Bonedigger has a job for life.

Benny follows his colleagues into the hallway. They each tiptoe past Benny’s snoring parents. They creep down the stairs and through the front room. Benny lingers in the entrance hall, gazing at the faded photograph of his mum and dad: the one taken at Blackpool Pleasure Beach before he was born. Benny never did like that picture. His father wears a 70s gravy-dipped moustache. His mother wears a floral sundress which flaps against her legs. Benny’s parents muddled along fine before him, and they’ll muddle along just as well after he has gone. Besides, they always knew he was different.

He grabs their picture from the wall and shoves it in his sack.

For little Benny Bonedigger, he won’t be coming back.