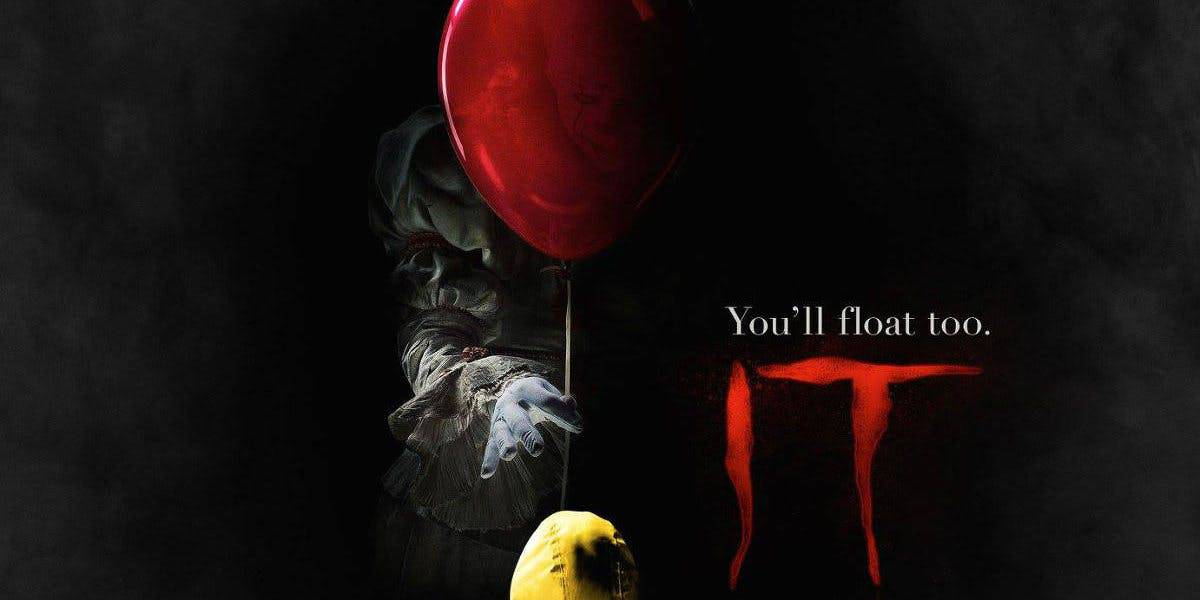

IT is a 1986 horror novel by Stephen King, first adapted for screen in 1990, and most recently in 2017. This blog post is about the storytelling of the 2017 film.

After filming ‘IT’ (2007) Bill Skarsgård had daily nightmares of Pennywise. In these nightmares, he would battle Pennywise just as the characters in the film do.

THE TERRIBLE MONSTER OF IT

I liked what one reviewer had to say about IT: The monster in this film is whatever the story requires him to be for the scene. Indeed, this monster is the ultimate shapeshifter, sometimes calm, sometimes unleashed. This monster is a writer’s dream — he seems to have no rules. Why doesn’t every horror writer create a monster like this? He’s awesome.

He’s also one-dimensional.

Here’s the golden rule about movie-length (or novel-length) stories about unpredictable monster villains with no redeeming features: Villain versus hero cannot, in itself, sustain a story. The character web is simply not interesting enough. Alongside the monstrous villain the writer must create a very human web of opposition. We see this time and time again in popular storytelling:

- In Twister we have man versus tornado, but the human opposition comes from a couple of professional storm-chasers on the brink of divorce as well as an entire band of rival storm-chasers who aim to beat our heroes in their storm-chasing game.

- In Jaws we have man versus shark, but the interest comes once again from the human opposition. Sheriff Martin Brody wants to close the beach, but this is opposed by local businessmen. Then there’s the most subtle, macho opposition between manly-man Quint and the others on his boat.

- In Jurassic Park we have man versus velociraptor, but a park employee attempts to steal Hammond’s dinosaur embryos, among other interpersonal opposition.

And in IT, we have the evil outside villain (the shapeshifting clown), but there is a very strong human gang of bullies who are just as scary. The gang of bully kids is a common way to flesh out a web of opposition, especially in stories about children. Suzie Templeton used the bully opposition web for her short film adaptation of Peter and the Wolf.

IT: MODERN MONSTER

IT is very explicit about the symbolism of the clown, and why it is a shapeshifter. But this is the typical modern horror monster. I have written previously: What is the horror genre for? IT is a modern horror, having moved away from Christian symbolism and into psychological symbolism. The monster is a representation of whatever terrible thing happens to be in your own life.

SETTING OF IT

Realism interpretation of the IT setting: There is no clown. Georgie Denbrough drowns while trying to retrieve his paper boat from a drain. The body is never found. Bill bonds with the others in his vicinity who each have their own significant trauma: incest, Munchausen syndrome by proxy and so on. The monster is different depending on who sees him. This is like the Mirror of Erised in Harry Potter. Whoever looks into it sees their own unfulfilled desire. The Mirror of Erised is a descendent of an old fairy tale device, such as the mirror in stories such as Snow White.

Horror is one of the three most symbolic genres in existence. (The other two are science fiction and Western.) Much has already been said about the symbolism and, frankly, if you’ve seen a lot of horror, it doesn’t need saying.

CHILDHOOD REALISTICALLY DEPICTED IN A STORY FOR ADULTS

One thing that struck me while watching IT: The smart aleck dialogue, especially the crass sexual jokes in the dialogue of Richie Tozier, felt realistic. The irony is that this dialogue would never be acceptable in books for children of that age. These kids are meant to be 13, which upper middle grade, lower young adult. In children’s literature you never read dialogue such as:

Richie Tozier : You punched me, made me walk through shitty water, dragged me through a crackhouse… and now I’m gonna have to kill this fvcking clown.

Richie Tozier : I hear the list is longer than my wang.

Stanley Uris : That’s not saying much.

Richie Tozier : Hey Eddie, are these your birth control pills?

Eddie Kaspbrak : Yeah, I’m saving them for your sister!

I have known adolescent boys who talk very much like this. Another difference between stories for adults and stories for children: Children in stories for children must function, to some extent, as role models. Child characters in children’s stories are more naive and wholesome than many real-life counterparts.

It’s not just the horror elements of this film which keep this movie out of children’s hands. The clown, all told, isn’t that scary for many kids. The clown is clearly a monster. But the stone throwing, the chase, the fat shaming, the mutilation on a boy’s belly — those elements all feel uncomfortably real.

CHILDHOOD SONGS SECONDED FOR ADULT HORROR

Listen to the IT soundtrack (composed and arranged by Benjamin Wallfisch) and you’ll hear a very creepy, echoey version of Oranges and Lemons, music box inspired atmospheric tunes and children singing, slowly and without instrumental accompaniment.

This technique is common across horror and thriller films. Quentin Tarantino understood the creepiness of Shivaree’s 2000 song entitled ‘Goodnight Moon‘ when he chose for the soundtrack of Kill Bill Vol. 2.

There’s a nail in the door

And there’s glass on the lawn

Tacks on the floor

And the TV is on

And I always sleep with my guns

When you’re gone

There’s a blade by the bed

And a phone in my hand

A dog on the floor

And some cash on the nightstand

When I’m all alone the dreaming stops

And I just can’t stand

On it goes. Fans of child literature, however, are more likely to think of the eponymous but innocent story by Margaret Wise Brown.

That link to the well-known picture book is part of what makes for the creepiness of the song. There’s something about the admixture of horror and childhood familiarities such as songs, clowns, circuses and picture books which intensifies the creepiness of the creepy bit. This is how the folk at TV Tropes put it:

If a program or film wants to add fear to a scene one of the most creepy ways is to have a Creepy Child, or a whole creepy choir, singing somewhere in the distance or background, usually the tune is a mournful nursery rhyme. Sometimes it will seem like the characters can hear it and they may even call out, asking if anyone is there.

Creepy Children Singing

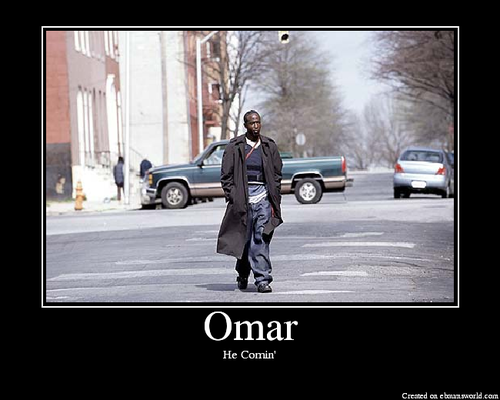

The Wire is a TV series for adults, creepy because of its uncomfortable realism. The character Omar Comin is particularly interesting, due to his role as sometime-comic relief, for his incongruous same-sex attraction in an overwhelmingly macho environment, and for his sociopathic ability to kill. Regular viewers of the show will soon learn that when Omar Comin starts to whistle Farmer In The Dell, bad stuff is going to happen. In this clip, bystanders realise from the whistle that Omar is up to very bad business.

Why Farmer In The Dell? Because viewers familiar with the tune will associate it with innocence, childlike naivete and comfort. The tune works well in the story because Omar is probably using one of his own childhood favourites for dual purpose: To set up a nonchalant persona for himself in the eyes of others, and also to steady his own nerves. The words themselves may also have thematic significance, though The Wire is not known for its ham-handed metaphors in the manner of Mad Men, so this may be an overanalysis.

The tinkle of bells, the fast-to-slow tune of a music box, the call of the ice-cream van — all make for excellent horror soundtracks and IT makes use of it too.

RELATED

10 Things You Might Not Know About Stephen King’s IT from Mental Floss

How IT handles the book’s most controversial scene from Entertainment Weekly