Best Loved Books

- Little Women

- Tom Sawyer

- The Secret Garden

- Or, see the Wikipedia category

- Literary scholar Michael Patrick Hearn considers the three most quintessential American novels to be Moby-Dick by Herman Melville, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum, and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain.

- The Rootabaga Stories are modern American fairytales (set 200-300 years ago). Few British children would know of them.

- In the years immediately after WW2 Johnny Tremain by Esther Forbes was a work of historical children’s fiction that stood above all others and which everyone knew. But in the 1970s it was damned as embodying an old-fashioned view of the Revolution.

Features Of American Children’s Literature

Often, as explained by Griswold: a child is orphaned, makes a journey, is adopted and harassed by adults, and eventually triumphs over them and comes into his or her own.

- This article from The Washington Post is about how American childhood has changed over the last few hundred years. Changes in childhood affect children’s literature, of course.

- On the whole American children’s literature is more down-to-earth because America’s earlier children’s writers rejected fantasy and escapism.

- When authors do do fantasy it’s often set in the old world (e.g. Madeliene L’Engle, Lloyd Alexander)

- American stories have tended to portray the family as a mini-nation. This applies to children’s books especially, e.g. Little Lord Fauntleroy, Huck Finn, Wizard of Oz. So many American children’s books can be seen as nationalistic tracts. We glimpse in them ‘America-as-Child’.

- Puritanical compared to Europe – closer to Russia than to Sweden in this respect. And compared to England, the trend was not so soon relaxed.

- “American publishers,” Nicoletta Ciccoli laments, “do not like the dark and disturbing. They love the mainstream.” (As a result, her illustrated children’s books for American publishers seem less challenging: employing a light palette and offering only hints of her genius with the weird.)

- Many mothers stay at home with their children

- America translates very few foreign books, and many of those fail to catch on

- European books don’t do well in America

- Rationalism

- Everyday situations

- Comic events

- Down-to-earth

- Material things in general

- Raised on a national myth of a strong and active hero

- Acquisition of material wealth preferred over spiritual knowledge and maturity

- The spirituality of European children’s literature is alien in America

- European children’s literature seems introspective

- Something has to happen in American children’s literature

- Churchy

- Against nakedness

- American classics advocate positive thinking. There is a substitution of psychology for religion. (The Secret Garden, Pollyanna, The Wizard of Oz are all good examples of Believe in yourself! Have confidence!)

- Although American classics include tricksters, there is a conviction that Adamic innocence alone is redemptive.

- Optimism, ignorance of evil and naivety is rewarded, and is enough to save a main character. (Dorothy is innocent, Little Lord Fauntleroy is especially optimistic. Pollyanna is the ultimate example.)

- American childhood classics are about physical health. But there’s also a vision of the world as a sick ward. (Little Women, The Secret Garden).

- There are lots of orphans in American children’s literature. A lot of the classics are based on the Cinderella ur-story.

Corrie and the Yankee by Mimi Cooper Levy and illustrated by Ernest Crichlow (1959)

A girl helps a Yankee soldier escape, which leads to finding her own freedom.

E. Nesbit’s failure in the United States is not entirely mysterious. We have always preferred how-to-do to let’s-imagine-that. In the last fifty years, considering our power and wealth, we have contributed relatively little in the way of new ideas of any sort. From radar to rocketry, we have had to rely on other societies for theory and invention. Our great contribution has been, characteristically, the assembly line. do not think it is putting the case too strongly to say that much of the poverty of our society’s intellectual life is directly due to the sort of books children are encouraged to read. Practical books with facts in them may be necessary, but they are not everything. They do not serve the imagination in the same way that high invention does when it allows the mind to investigate every possibility, to free itself from the ordinary, to enter a world where paradox reigns and nothing is what it seems to be; properly engaged, the intelligent child begins to question all presuppositions, and thinks on his own. In fact, the moment he says, wouldn’t it be interesting if…? he is on his way and his own imagination has begun to work at a level considerably more interesting than the usual speculation on what it will be like to own a car and make money. As it is, the absence of imagination is cruelly noticeable at every level of the American society.

New York Times, opinion piece by Gore Vidal

A Brief History Of American Children’s Literature

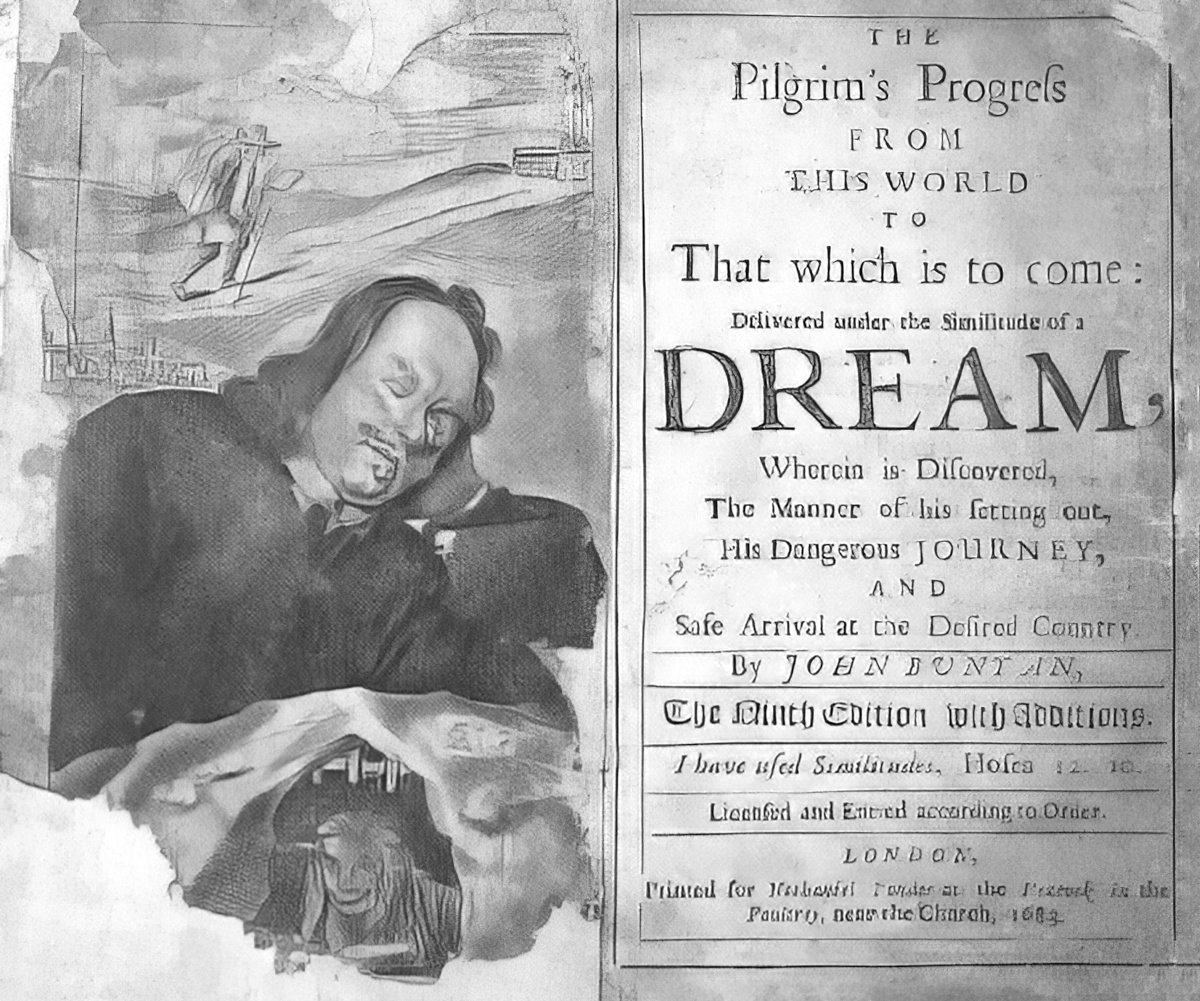

In the early 18th C, besides the Bible and the New England Primer, the staple items of approved reading were Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress, Watts’s Hymns, and Divine Songs, and Janeway’s Token for Children with American additions. There were many other memoirs of pious children, admonitions from solemn and forbidding divines, and legacies of advice from father to son or mother to daughter.

But Defoe and Swift soon crossed the Atlantic. There were also the chapbook versions of such old stories as The Seven Giants of Christendom and Valentine and Orson.

The Babes in the Wood and Tom Thumb sold particularly well.

Sometimes it was possible to combine dreadful warnings with sensationalism e.g. The Prodigal Daughter, who makes a bargain with the Devil to poison her parents.

For most of the 18th C America was still colonial, so ‘American children’s literature’ didn’t exist — the cultural capital was London. That said, there were printers in Philadelphia and Boston. They would often change minor details in British books to Americanize them.

For the 100 years following Newbery’s death there were main types: didactic and commercial American books for children. They were written for ‘respectable’ children, for future masters and misses of the middle classes.

In the 1850s there was Tom Brown and Eric (boys’ school stories).

Miss Charlotte M. Yonge preceded Louisa Alcott’s Little Women by writing domestic stories for girls.

In the 1860s: two great fantasies: Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland and Water Babies.

The period 1865-1914 was ‘The Era of the Child’. Several intellectual trends contributed to this: Nostalgia (because the second half of the 19th century was dramatically different from the first half. The Civil War changed everything, urbanization), Fascination With The Future (there was the laying of the transatlantic cable, the completion of the Union Pacific Railroad, telephones, electric lights, first flight, and children were symbols of the future), Progress Through Recapitulation (nearly all the big name American writers of this time were often on steam ships, crossing the Atlantic and were early adopters of tech, and this seems contradictory since they were writing about childhood idylls, but adults of this time were able to regress to the psychic age of their children in order to write for them), Changing Attitudes About Childhood (children were less indulged before this era, which became a lot more middle class with free time for the masses), New Interest In Child Raising Practices (parents were careful about not sullying their children’s innocence, the first paediatric clinic was established in NYC, parents started to think about how they were parenting and realized that ‘parents’ were responsible for children’s needs), The Child As Public Figure (before now children were mostly raised in rural areas but now they were the center of American cultural life, vehicles for nostalgia, symbols of the future, put on stage for the first time. No longer seen and not heard.)

Escape from slavery is a common theme in historical fiction. (e.g. Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain forward). The outstanding novel about slavery is The Slave Dancer by Paula Fox (1973).

On Harriet Beecher Stowe’s “Uncle Tom’s Cabin”: A Discussion with Robin Bernstein

By the early 19th century, slavery was still a brutal reality in southern U.S. states, and a growing movement to abolish slavery nationwide was taking hold. In 1851, Harriet Beecher Stowe published her first novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin. It was intended to be an anti-slavery book, to provide a positive view of Black people in America. But it also has another, more complicated legacy, unintentionally birthing new racist stereotypes. Professor Robin Bernstein is a Professor of African and African American Studies and of Studies of Women, Gender and Sexuality at Harvard University. She is the author of Racial Innocence: Performing American Childhood from Slavery to Civil Rights as well as Cast Out: Queer Lives in Theater and a children’s book titled Terrible, Terrible! See more information on our website, WritLarge.fm.

New Books Network

In the 1870s: Tom Sawyer, Black Beauty. Before The Adventures of Tom Sawyer by Mark Twain there were two general kinds of American Children’s Literature: Aesopian tales of Good and Bad children (finally codified in the Sunday school story), and spiritual biographies of woebegone but saintly waifs (a genre that eventually became the stories of the child-victim in sentimental fiction). But Clemens too on the first kind of story, turned it on its head and celebrated the Bad Boy. Tom Sawyer also lampoons the second type of story.

Sometimes a superficially didactic aim was used as cover for sheer fun e.g. Vice in its Proper Shape: or, the Wonderful and Melancholy Transformation of several Naughty Masters and Misses into those Contemptible Animals which they most Resemble in Disposition, Printed for the Benefit of all Good Boys and Girls

The 1920s was a great decade for American literature, whereas it was going through a down period over in Britain. There were now specialist courses for children’s librarians and the first children’s editor was appointed by Macmillan of New York in 1919. Other American publishers followed.

Between the wars the best American fiction tended to be about European settlement of the East Coast, the War of Independence and the drive to the West. The viewpoints were white Anglo-Saxon, since this is who was writing them.

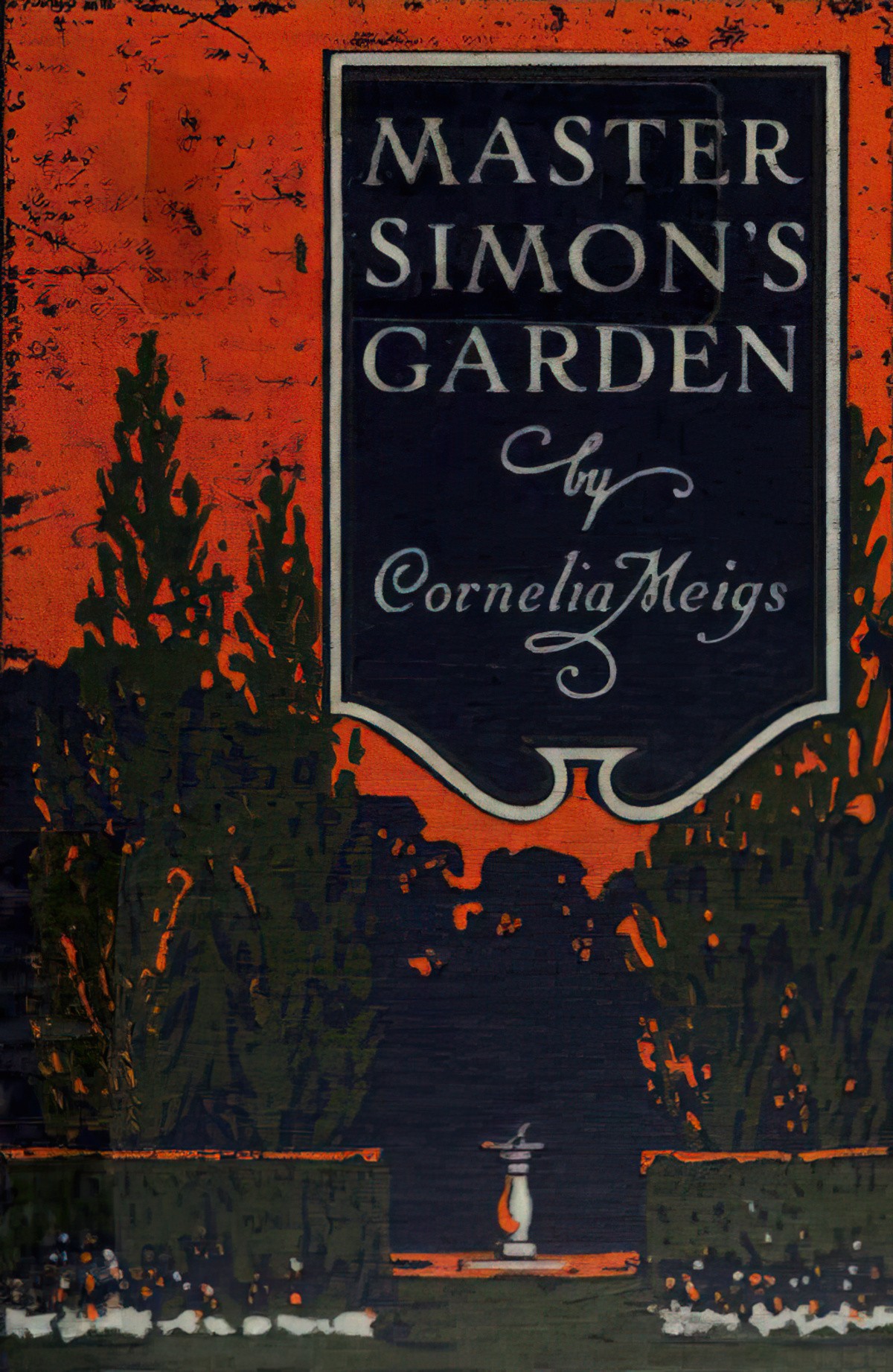

Master Simons’s Garden (1916) by Cornelia Meigs was an example of this kind of between-war American children’s literature, and was influential for what followed.

Little House on the Prairie is fictionalised autobiography — things in the series actually happened and the people were real, but Wilder’s life was significantly harder than that portrayed in the books. The message is that ‘happiness is not related to material possessions’. The best of the books is thought to be The Long Winter.

Caddie Woodlawn (1935) is another book (a Newbery award winner) that looks west.

Johnny Tremain (1943) is set in Boston at the start of the Revolutionary War. Unlike Caddie Woodlawn, this is a true historical novel.

Picture books have blossomed since 1945. There have been great technological advancements in printing and growing awareness of the importance of books for young children. Maurice Sendak is regarded by critics as the best of the past 100 years or so.

It took some time though for excellent American children’s literature to come out of the more welcoming environment. Some of the early Newbery Medal winners aren’t actually all that great.

Even today there is a difference between Europe and America regarding what is good for children to be reading:

I finally made a stand — I gave the good and defensible reasons, heard no more, and thought with smug satisfaction that here was one author who couldn’t be bullied into submission. Poor innocent fool! On receiving my advance copies from the States, what did I find? In the face of my bold authorial intransigence, the whole speech had been wiped out entirely. I could, of course, have got back to the publishers and made tremendous waves … but equally of course I didn’t. I bowed in the end to the inevitable economic pressures.

British YA author Jean Ure on using ‘four-letter-words’ in her novel One Green Leaf

In the middle of last century kid-lit tended toward idyllic or slightly humorous (Vera and Bill Cleaver, Elaine Konigsburg, Beverly Cleary). The 1950s were a peaceful era in children’s books. America had what Ann Durell (a distinguished editor) called “the Indian summer of the Eisenhower years” when “society was dominated by a sort of mid-Atlantic bourgeoisie that felt it had saved the world for democracy and had thus earned the right to perpetuate forever the sociological and cultural values of Edwardian England.” The children’s book world in the US was solidly Anglophile. “It seemed that almost any book published in London would have an American edition sooner or later.” There was an unwritten ban on lying or stealing, unless punished. No drugs, sexual suggestiveness, drinking or smoking.

In the 1970s and 80s there was a trend towards problem oriented books (Katherine Paterson, Cynthia Voigt, Betsy Byars). This happened in the shadow of the Cold War, which people were worried that a bomb could decimate the entire world. This had never been a threat before, of course.

Alongside the problem oriented stories fantasy has also thrived (Lloyd Alexander, Madeleine L’Engle, Susan Cooper, Natalie Babbitt, John Bellairs, Jane Yolen, Anne McCauffrey, Robin McKinley, Meredith Ann Pierce etc)

The difference between books ‘for girls’ and books ‘for boys’ is clearer than for example in Asian countries, where people like Hayao Miyazaki are confidently making mainstream movies for children starring female protagonists, without expecting that ‘boys won’t be interested in stories about girls’ (but not vice versa). This is surely related to a culture which romanticises masculinity:

I recently heard about a study showing that in the United States, girls three to six years of age have a much better ability to regulate their emotions and their behaviours than boys of the same age. Interestingly, this gender difference in self-regulation wasn’t found in any of the three Asian cultures included in the study. The lead author’s take-away was that here in the US, we expect girls to be more self-regulated than boys.

Boy Behaviour or Bad Behaviour from Good Men Project

The characters in many American children’s novels take for granted that anyone, no matter how humble, can improve his or her lot in life and achieve a dream. That basic, unquestioned assumption defines them as Americans. It is not shared so unquestioningly, however, by the British animals in Wind in the Willows, who tend to be content with the way things are, and who get into trouble when they try to live out their dreams. – The Pleasures of Children’s Literature, by Nodelman and Reimer. (See Downton Abbey for the adult equivalent of this British tendency in fiction, to punish characters who ‘don’t know their place’.)

While British children’s literature encourages children to grow up, American children’s literature holds up the ideals of domestic Utopia. This happened after WW2 after several decades of economic deprivations and war had deprived Americans of the pleasures of domesticity. (This same ideal had significant consequences for feminism, too, with the domestic ideal requiring a housewife, preferably in curlers and an apron.)

Even in postwar decades, American children’s literature was exceptionally idyllic. Then writers such as Katherine Paterson and Patricia MacLachlan came along. Their stories departed abruptly from Arcadia.

In the 1960s American children’s literature got a big boost by Title 2 (of President Johnson’s Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965) which made huge funds available for book purchase in schools.

Family life was exemplified in the reassuring pages of Eleanor Estes, Elizabeth Enright, Madeleine L’Engle et al.

In 1965 there was a seminal article in Saturday Review on “The All-White World of Children’s Books“, so the discussion has been taking place since then (with not all that much progress). There already existed books about black children but they were written by white authors and implied that black children were really white under the skin.

The first outstanding black author for children is sometimes thought to be Virginia Hamilton. She was certainly the first “black woman and black writer to have received” the Newbery Medal.

Another black writer Mildred D. Taylor also won it a few years later for Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry.

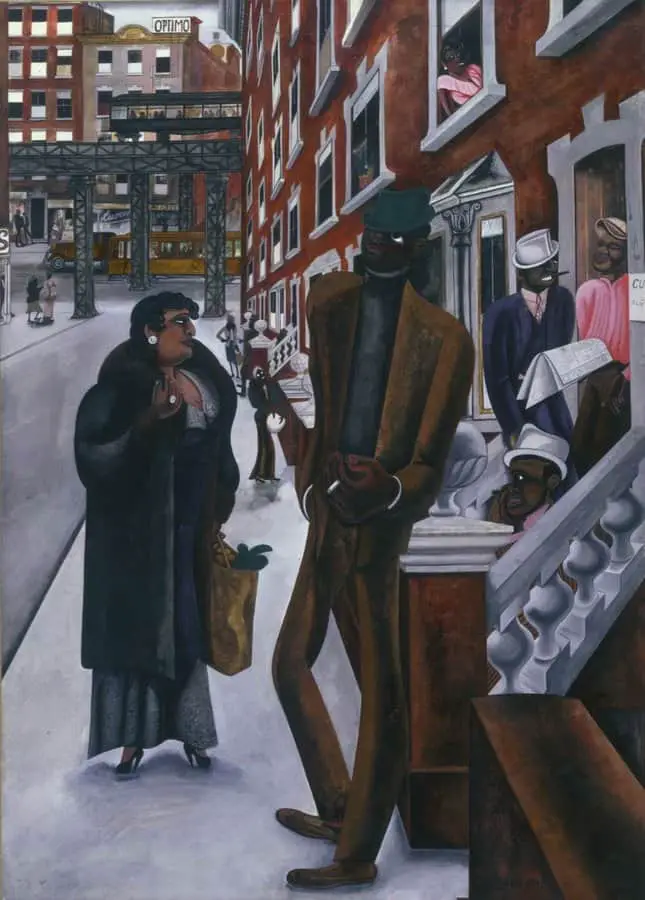

Walter Dean Myers sets most of his stories in Harlem.

For more on this see the history of School Library Journal, from SLJ themselves

Books started to reflect the change in family dynamics, preparing children for the possibility of broken families.

Adolescence was portrayed (and perhaps experienced) not as not a time of boundless energy for life but a time of negative rejection of adult values. Adults were no longer automatically entitled to respect.

Authors were faced with the tough job of writing about an adolescence they hadn’t experienced themselves. There was a big gap between generations.

Parents were often useless or vicious, e.g. the novels of Paul Zindel.

In the 1970s there was backlash against feminism and anti-racist groups, and a bunch of book banning.

There was also a recession in the 1970s which affected the economics of publishing both in American and Britain. Initial print runs were smaller which raised the price of individual units. Libraries did their best to buy new books but didn’t replace as many old ones. High warehousing charges didn’t help, especially backlists — the majority of books which sell slowly but steadily, if they’re allowed to. Traditionally, children’s books were published for the long term, but now, if a book didn’t immediately take off, it would fall out of print. This made it more difficult for writers to establish themselves.

The Indian In The Cupboard brought race issues to children’s literature

The publishing industry since the 1980s has been more welcoming of new writers than Britain has. There is stronger institutional support. The 1980s were good for children’s literature, and children’s book shops were said to be the fastest growing retail sector.

But by the 1990s that was no longer the case. The Association of American Publishers reported that sales of juvenile hard covers in 1993 were down by 8%. Paperback sales were up by double that, but lower than in previous years.

Header illustration: Woman’s World Magazine February 1918 cover art