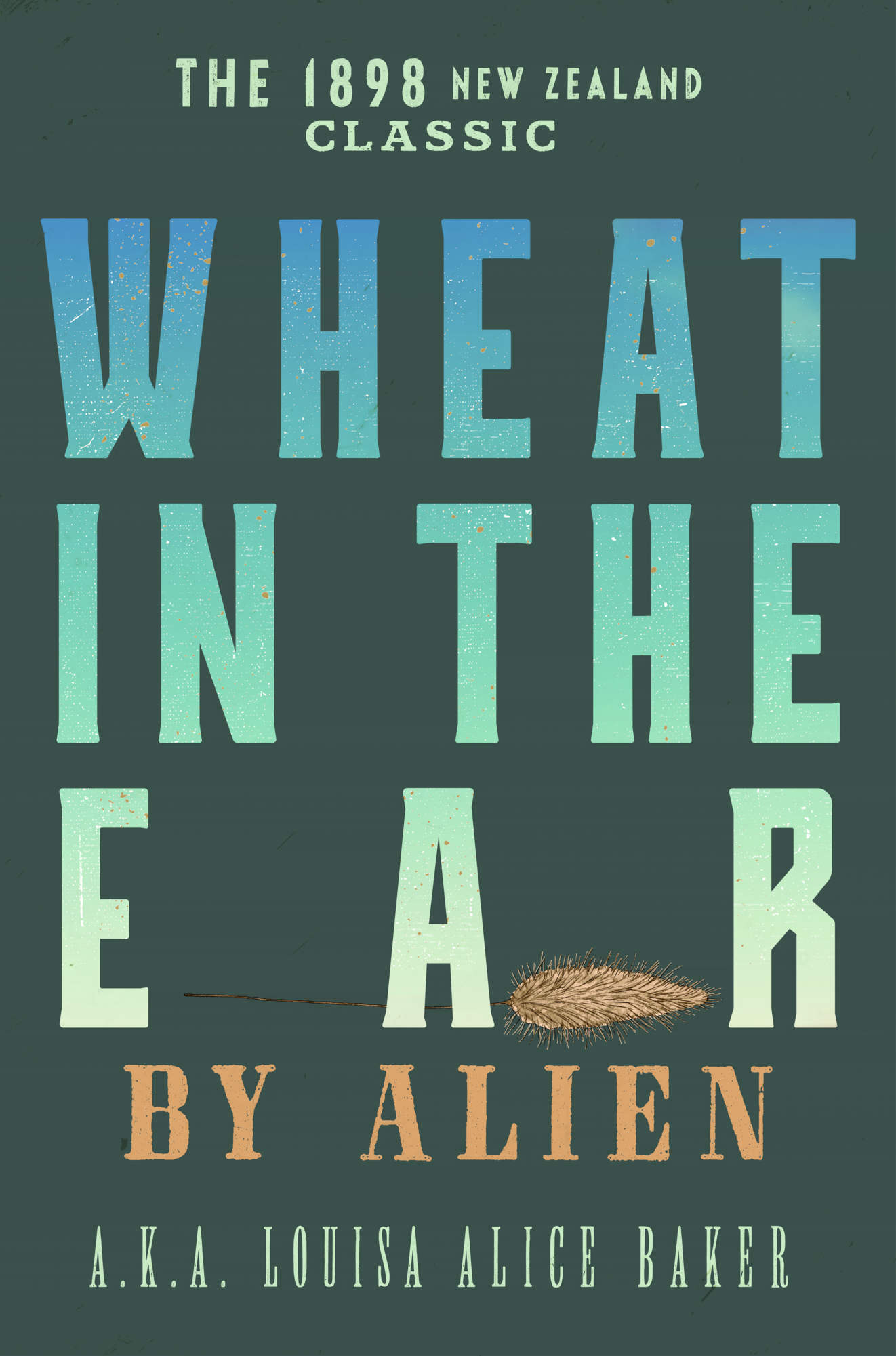

I considered recording this New Zealand classic as an audiobook, and set about simplifying the text for a contemporary listening audience–and also, to help myself concentrate on it.

But I gave up the idea. I’m not sufficiently in love with it.

However, it’s still interesting to read some 1800s Aotearoa melodrama. Below you’ll find the first few chapters rewritten (but not otherwise condensed) followed by my increasingly eyebrow-raised summary, haha.

THE CRY OF THE CHILD

1873

Autumn wind travelled from the Pacific Ocean, ruffling the surface of snow-rivers, sweeping the vast Canterbury plains. It bent the long tussock-grass, undulating like sea-waves—or like dun waves in evening shadow—except for shafts of sunset-gold, as it travelled from the Southern Alps which bordered the western horizon.

Mile after mile of warmly-tinted, native New Zealand grass spread to the distant blue-black mountain range. Here and there, clumps of trees broke the monotony of the landscape. Above the trees, the occasional outline of a roof was visible. Smoke ascended from domestic fires. Near these homesteads, cloud-like flocks of sheep nibbled the short, soft grass that grew between silky tufts of tussock.

The deep silence was unbroken, except for the muffled rhythmic thud of horse-hoofs on turf. Horse and rider went mountain-ward in the glow from the west, clearly familiar with the landscape, as if journeying homeward—the rider to a fireside[ The author died aged 70 in hospital, the day after suffering extensive burns due to a stove fire in her home.] and companionship, and horse to stable and corn.

They looked more weather-proof than picturesque, hardened to the beating and buffeting of storms. The man rode with ease and elegance. His seat was firm but his long legs, covered to his leather leggings with a rough coat, stuck out from the horse’s sides. The brim of his oilskin sou’wester flapped with each step, and the leather bag strapped to his back bulged out behind. His short, grizzled beard was blown by the wind. Altogether, he presented a rather aggressive and disreputable appearance. But this rider was in fact a prosperous, simple-hearted farmer, riding home to his wife, Janet.

The fantastic shapes of the clouds before him reminded the rider of the spires and domes of London, where he, Tom Jeffries, had worked in his youth as an engineer. With little opportunity in England to grow his wealth, he and his wife had emigrated to New Zealand, fifteen years ago.

Trusting to Providence had paid off. Though his face had become rugged, at forty years of age he retained in his grey eyes the sparkling enthusiasm of youth. He now called New Zealand “home”, and had given up thoughts of returning to the land of his birth. So long as he were with his practical and loyal English wife, the colony felt like home. Still, reminders of England did make him smile.

Tom had brought his new wife to a sod hut of two rooms, with a floor of earth and roof of shingle. Tom had built it himself on the fifty-acre section purchased on the banks of the Ōtira Gorge, a swift-flowing stream which started in the white snows of the mountains. This hut had not been weatherproof. When sou’westers raged, the young bride and groom had bunkered down beside their domestic hearth, under the shelter of a large umbrella. But hardship had not crushed the couple. Acre had been added to acre, with goodly flocks and herds. A substantial house now stood on the old site of the original hut, whose one tiny window had glowed like a beacon on many a dark night when Tom, like tonight, had pressed blithely towards it across the tussock sea.

The crimson shaft drew in from the west. The short twilight before day deepened for a moment, as Tom rode closer home to his wife’s welcome. He always thought of Janet on these rides. He was not a sentimental man. He had proven himself capable and self-reliant. He pursued his goals decisively. But simple faith in Janet had kept green his heart.

Janet represented the spiritual. In protecting her, he imagined he absorbed her. He stood between her and every adverse wind that blew.

For all that, Janet had one eccentricity that Tom had failed to eradicate. It dated back to the days of the original sod hut. Janet craved a child. But there had been no child. And Janet refused to take the disappointment of years and put this craving to rest. At first she wept abundantly in secret, but nothing destroyed her hope. The weeping did stop, but she replaced this with industry, to one end. Everything she did left the fingermarks of the mother. Every enterprise, every thought, was directed to the future of a child who did not exist.

At first Tom laughed. Then he tried to console his wife. Finally he joined in, eventually surpassing Janet in her preparations for their son and heir. He consulted the non-existent wishes of the unborn regarding agricultural concerns which, after Janet, were the delight of his life.

The simple couple saw nothing strange in acting as the agents of an unborn child. The borders of pastures were extended, cattle multiplied and green wheat ripened to the ear. Each year, rain and sunshine imparted a deeper tinge of yellow to the white stone house on the gorge. And then the woman’s deferred hope became prophetic—she was soon to become a mother.

The man urged on his horse. A thousand tender and vagrant memories had accompanied him all the way home. But as he drew nearer, a new fear arose, and stalked like a ghost through the twilight. His firm hands trembled on the bridle. All this time, he’d been glad about the child, but had not feared for his wife. But suddenly the air became laden with the anguish of woman’s travail. The wind sighed through the grass. Distant sheep bleated. With his lips compressed, Tom’s eyes strained through the gloom for the coveted light of the farm-house windows. Only one thing concerned him now: the safety of his wife. His flesh contracted; his bones ached with anxiety to know how she fared.

So he dug his spurs into his horse, and felt the quivering flesh beneath him.

Years later, Tom Jefferies would tell a despairing girl on these very plains how it was on this night, with the wind shrieking round him like a woman in agony, of how this night afforded Tom his first glimpse of how loss might feel, and of how he staggered in from the darkness, weakened by fear, to the thrilling sound of the cry of a child.

FATHER AND MOTHER

Ōtira Gorge Farm took its name from the stream upon whose banks it stood—a burn-like stream that tumb led helter-skelter from the mountains, over rocky boulder, through fragrant fern to reach level land. Here, with occasional rebellious swirl and eddy, it gradully quieted, narrowing in parts to a steel-like blade that flashed between long grasses. Then, with swift curve, the stream grew opulent and broad, and then still.

The farmhouse stood back from the stream, its grey whiteness thrown into relief by a dark patch of native bush at its rear. The house was made of stone, with bulging windows and a porch massed with a late-flowering vine. Round three sides of the house was the orchard, despoiled of its late harvest. A well-kept lawn spread beneath the fruit trees. These trees were encircled by meadows, bordered by the gorge. Beyond the gorge were the far-reaching plains. The back of the house faced the bush and the mountain ridge. A veranda ran the length of the house.

In the space between the veranda and the skirt of the forest, a small world intervened: flower-gardens, kitchen-gardens, yards, dairies, butteries, hen-coops, and cow-sheds. Blazing autumn blossoms, yellow pumpkins and white-hearted cauliflowers, red tiles, brown-thatched roofs, glinting milk pans, and all the stir of the feathered tribes—ducks, fowls, geese, turkeys. All flaunted their colours in the autumn sunlight. Each contributed to the symphony of the farmyard, accompanied by a distant bleating of sheet, the lowing of kine[ An archaic word for cows], and the occasional bark of the watch-dog.

The great kitchen and the living-room of the house overlooked this scene from the windows under the veranda. The kitchen was spotless, ruled by the handmaid named Mercy. Farmhands marvelled at the clean boards and the shining steel around the stove. A tremendous table occupied the centre of the room, and three times daily, farmhands gathered round.

The roof had no ceiling. Great hams, flitches of bacon and yellow pumpkin hung from the rafters and from the large presses which occupied the space on each side of the fireplace. A faint aroma suggested dried apples and preserves. Over the mantelshelf the dish-covers flashed like breast-plates of steel. The delf and china on a huge dresser reflected a miniature kitchen whenever they caught the light.

Mercy was upstairs “cleaning herself”, and so the only occupant of the room was a tabby cat, who snoozed before the fire with her forepaws on the fender.

The living-room was decorated in snow-white and crimson—curtains, sofa, deep-seated chairs. Lavender bulged from two large bronze bowls on the mantelpiece, one on each side of the eight-day clock. Sheep-skin rugs had been bleached, combed and spread luxuriously before the fire, under the mahogany dining-table, and wherever they fit. On one side of the room stood an American organ. The deep-silled window blazed with geraniums.

In the fading light of the afternoon, Janet Jeffries sat on a low rocker, nursing her child in front of the hearth. She was essentially a fire-side woman—a faithful wife, affectionate mother, able manager. Both mother and child appeared to be asleep, lulled by the stillness. But a closer look revealed the woman’s downcast eyes rested on the face of the babe at her breast. At thirty-five years of age, Janet was not a young mother. Work and apprehension had drawn a mark or two across her forehead, but she retained the look of hope and affection.

Tom and Janet had wanted a boy, and had remained sure they would get one. They’d decided to call him John. But then, a daughter was born. It took Tom a while to readjust his expectations. Being a girl, this child would never have a remarkable career in the public eye, like a second John the Baptist. Denied much learning himself, Tom had wanted a good education for his son. While Janet was pregnant, he even rode his horse all the way to Christchurch to borrow biographies. These he would read to his wife’s pregnant belly while she stitched.

But now he had been stuck with a daughter, the educated hope, too, was dashed.

As for Janet, as soon as she heard the first cry of her new daughter, she did not feel robbed of a son. She mentally counted the linen sheets she would give her daughter at her wedding.

A stir in the kitchen announced that Mercy had come downstairs. Presently she appeared in the living-room with her mistress’s tea. Mercy was a tall, gaunt woman of twenty-five, with the muscles of Hercules and a mahogany complexion. She scorned men and was devoted to women. Her other concerns in life were her accomplishments, cooking and scrubbing, her reputation, her bitter tongue, religion and honesty.

Tom wasn’t the worst man she’d ever met. This couple were comfortable and happily positioned, living fifteen years with very little distress between them. Mercy couldn’t understand why Janet had wanted a boy about the house. He’d be a daily vexation. His boot-nails would ruin the floors, he’d steal the jam and grow to idleness. He’d live riotously and afflict pain on his mother.

As soon as Mercy learned the baby was a girl, her temper softened. Respect for her mistress increased.

Mercy deposited the tea try at Janet’s hand, then left immediately in case Janet asked her to hold the child, which she feared to break. In her haste she ran into the master, who was entering the room. He’d entered without noise, having left his boots in the lobby. The place of the baby was holy ground, and he stepped lightly to avoid waking her. So he came forward in his grey worsted stockings, and there he stood, six feet tall on the hearth-rug, looking down on his wife and daughter with satisfaction. In his shaggy greatcoat he had the look of a big sheep-dog, and brought in with him a whiff of frosty freshness and scent of tussock. After assessing the situation he put forth his strong roughened hand and touched Janet’s hair.

“Well, Mother!” he said in a hearty voice, as though there were no doubt about it.

“Well, Father,” she replied, “you’ve got back. You’re done for today? Go and get your supper, then come and tell me all about it. You’ve registered her ‘Joan’?

Tom’s bronzed and roughly-carved face lit up good-humoredly. He made no movement supper-ward, but said instead, “Joan. Joan Jeffries, daughter of Tom and Janet Jeffries, of Ōtira Gorge Farm, Ōtira Gorge, province of Canterbury, New Zealand.”

Janet hummed softly in contentment. “Heigh, ho! Daisies and buttercups, Fair yellow daffodils, stately and tall! When the wind wakes how they rock in the grasses, and dance with the cuckoo-buds, slender and small. Here’s two bonny boys, and here’s mother’s own lasses, Eager to gather them all.[ This is a verse from “Seven Times One” by Jean Ingelow. There’s no tune, though at times it may have been set to one.]”

“Joan,” reiterated Father, as though bestowing a name on Janet’s baby must add new dignity to the memory of the woman who made it famous. “Joan of Arc—Joan Jeffries! The name of a noble heroine!” He pronounced it hero ine—“fearless in danger; lamb-like in gentleness.”

Janet continued to sing from the poem by Jean Ingelow[ English poet and novelist Jean Ingelow (pronounced in-jah-low) lived from 1820 to 1897. Her work was widely read in her lifetime.]. Tom went to the kitchen and left his wife to her rocking. Later he returned to the room, his feet in carpet slippers of a gorgeous hue.

Janet noticed the slippers but made no comment. She knew why he wore them. Tom carried the leather bag in his hand. He sat down opposite Janet, unfastened the bag and drew forth a rattle, an India-rubber doll, a skipping-rope and a Bible.

For the first time, this bag did not contain a present for herself. She held the child a little closer. But she suffered only for a moment. The next, she congratulated herself on being a most fortunate woman.

HER NAME WAS JOHN

By the time baby Joan had cut her teeth, Tom had gotten used to being a father, and Janet sometimes even wished he’d mind his own business. But, with the spirit of a true egotist, Tom could not take a commonplace view of anything. Where things happened in his realm, Tom’s electric enthusiasm would sooner or later make itself felt.

Joan was developing tantrums. So when his daughter turned three, Tom brought home a little birch. Not that he meant to use it, but it might convince everyone concerned—himself included—that he was not one of those weak fathers who spare the rod and spoil the child.

But Janet was not happy about it, and redirected her husband’s attention towards his sheep and calves.

“That child is the mistress of the situation!” he said.

Janet just sighed. “Well, what do you expect? She’s her father’s daughter. You never would come second to anybody. Joan’s like you, bless her little heart.”

So Tom took himself out to the calves, deciding to curb himself to set an example.

Although the man still followed his agricultural pursuits with ardour, and packed his days with activity, he had a new source of joy these days. New feelings. Even the toiling, patient oxen seemed to look at him with his child’s wistful eyes.

Janet was keenly attuned to the child’s slightest mood, even while busy all day with her maidens and the dairy and the presses. Her religious sense had never moved her to fervour, but she wanted the best for her child. Janet could help her own child here in this life, but couldn’t guarantee what happened in the after life. So she decided it was time for the child to be Christened. If there was any virtue in infant baptism, it would be a pity to miss it. Tom saw that his wife’s mind was made up on the matter, and submitted gallantly.

So, in early winter they went ahead with it. The morning was dusted with silver hoar-frost, keen and sweet. An excellent morning for a baptism. Before the sun had dried the mist off the cobwebs on the gorse hedges, their buggy was bowling from the farm door. Tom drove and Janet sat behind, holding the child in a bundle, well down under the rugs.

Fifteen miles stood between the Ōtira Gorge farm and the nearest church, so the early start was necessary. They passed through the home enclosures and paddocks with the sun still low. Clinging billows of vapour rolled over the plains, and the scene opened up to them only as they advanced through it. In early-morning fog loomed the granaries and woolsheds, there a hayrick, now a plough with horses and driver, with long, freshly-turned furrows of brown earth. Trip-trop-trop went the horse’s hoofs as they travelled swiftly through the fresh, ferny smell of tussock. Tom spoke cheerfully along the way, and Janet felt her blood run warm with a half-forgotten sense of youth and well-being. She was free from the four walls, without churning and baking to worry about. The ever-widening view thrilled her with anticipation. Of late she had been losing touch with nature, but now, on the way to her child’s baptism, she felt she could get at the great heart of things, for the child’s good. The child would free her from her materialism and pulseless egotism.

As for little Joan, she craned her neck to see all the world she could with her wide and bright-grey eyes.

The little church was built on the outskirts of the straggling township—a cheerless building with a corrugated iron roof, standing in an uncultivated paddock. The incumbent of the parish happened to be away on holiday. So when the small Jeffries family made their way up the church steps, passing out of the morning sunshine and onto the strip of cocoa-nut matting to the font, they were received by a severe-faced stranger. The man was very old, very bald and very deaf. He fixed his penetrating eyes first upon Janet.

Janet trembled and coughed apologetically. “We’re sorry to trouble you,” she said.

Then the old man fixed his gaze on Tom, and lastly on the rosy-cheeked child, clearly displeased and wanting them to know it. Janet burned at the stern looked directed towards her lambkin. Her instinct was to snatch up her treasure and run. Instead, she looked first at her beautiful child, then at the stained glass window, representing Christ wearing His thorn crown. From His outstretched hands, a light shaft streamed upon the child. So Janet decided to stay.

The old clergyman drew closer to Joan, and Joan didn’t like it. She was making quite a fuss.

“Name this child,” ordered the old man.

“Joan,” said Tom, with his head in the air and shoulders back.

“John it is,” snapped the deaf clergyman, “and do sign him with the sign, in token that he shall not be ashamed, and manfully to fight…”

Janet thought to correct him, but Joan was further insulted with the old man threw cold water on her face. She only yelled louder.

“I won’t fight! I won’t, I won’t!” she screamed.

And she never did, at least not as an orthodox Christian.

JOAN’S BOYHOOD

Until the day she died, Joan’s mother blamed the christening for her daughter’s shortcomings. What chance did the girl have, having been christened with the name of a boy?

She didn’t blame John the Baptist, for her daughter’s being named John. Nor did she blame the grumpy clergyman. She hoped to be old herself one day, and quite expected to be deaf. But, with her husband’s obsession with John the Baptist, combined with the bungling of the clergyman, her daughter was the first Christian to ever be called John.

No wonder the child was tomboyish. Who could expect otherwise? It did not occur to Janet that physical law, and her own parental influence had anything to do with it.

At first, Joan was called “Johnnie” as a form of reproach, whenever she failed to live up to the behaviour of good little girls—when sitting sideways on a chair with legs dangled over the rail, or when tearing up her muslin pinafore to make a tail for a kite.

Mercy the housemaid shook her head. She blamed the parents for wishing for a boy instead. They got what they ordered.

Tom was not worried about his little Johnnie. He hoped his child would grow up with a nice blend of masculinity and femininity—with the honour of a gentleman and the sweetness of a woman. A bit of masculinity would not go amiss.

“The word of a gentleman is his bond,” said Tom, in his strong, cheerful voice. “He’s courageous and honourable. Graft that to the patience and gentleness of a woman, and what have you?”

“We’ve got her father’s own girl here,” answered Janet, with conviction. “She won’t stand the whip, nor yet the curb[ Curb: a type of bit with a strap or chain attached which passes under a horse’s lower jaw, used as a check.], bless her!”

Each parent created a seaprate world for the child, made up of staid philosophies, middle-aged experiences, and the grit of individual knowledge. But Joan—or Joan-John—with a young soul’s prerogative, went a new way of her own. As soon as she could balance herself on an unmade path she was outside the home enclosure, paying no mind to her mother’s cautious fears. She readily paid tumbles and scratches as toll for curiosity. She chatted to the cattle in the field and byre[ Byre is a British word for a cowshed. The author was born in England and moved back in midlife. Even New Zealanders born in the colony sounded more British than they do today. Into the late 20th century, white people who never once set foot in the United Kingdom might still refer to the United Kingdom as “Home”.], investing them with human individuality, telling them off as she herself was reproved. It did not matter to her that they were cows, and therefore immune to dogmatic reformation.

Before she was seven years old, Joan-John knew the feel of every wind that blew. She knew the history of every live creature about the farm. She could tell the seasons by the smell of her garments, for they bore the scent of newly-turned earth, the fresh-mown hay, or the mellow odour of clover and ripe corn.

Her mother Janet dressed her up in scarlet because the colour could be seen from afar. It vexed the woman’s housewifely and orderly soul that her child took so kindly to the fields. She wanted a thrifty, domesticated, responsible daughter. Instead she got a child who refused a doll, and practised whistling.

For economy’s sake, Joan-John’s skirts were kept short to the knees, and her sleeves to the elbow, thus leaving bare her brown arms and legs. She was clothed in hardy serge, and as little of that as was consistent with decorum.

But for all that, Joan-John was a good-looking child, with dark brown hair curled under a red fez, with large, bright-grey eyes like her mother and about them a suggestion of her father’s humorous wrinkles. When Joan-John wasn’t singing or whistling, she was grinning.

Joan-John had not yet emerged from the animal state, but her mother had made strides in civilisation and was anxious for the progress her little woman. One day, Janet took the child’s tiny hand in her own work-worn palm and looked critically at it.

“Sakes! What a mite of a thing!” Then, as though a happy thought had struck her, she added, “It’s a hand to do beautiful needlework.”

Joan-John looked at her mother dead in the eye, than glanced at her imprisoned right hand disapprovingly. The delicate lines of her little chin began to harden.

“I never could get the way of that marvellous embroidery myself,” Janet continued. “A bit of muslin and a fine needle were lost in my hands. Still,” she added hastily, catching a sigh of relief from little Joan-John, “when I was your age, I could sew my seam.”

Joan-John withdrew her offending member from her mother’s grasp, put it behind her and looked steadily from under the charming dark curls about her forehead.

Janet smiled benignly. “Yes, I could sew my seam, and dress my doll. My doll was neat as a real lady.”

Joan-John glanced at a dilapidated object on the couch. The doll leered back, from under a rakish and ragged hat. Joan-John put herself between her mother and her doll.

Janet, with some difficulty, repressed a smile, much enamoured by the small culprit before her. She smoothed her apron, passed her hand over her hair, then continued. “My mother did not believe in too much play. Whenever I was too restless, and impatient for the field, my mother would pin me to her knee, dearie. Pin me, till I had finished my seam.”

Joan-John stood on tiptoe. Now her mother’s anxious face was level with her own.

“Sounds miserable,” she said. “I’m sorry for you.” Next, she placed a sympathetic kiss on her mother’s face and bounded out into the sunshine.

Mercy joined her mistress, and the two women watched Joan-John as she gambolled about outside.

“Children is the climax of misfortune,” Mercy began, repeating something she’d memorised from her reading material. “Man and marriage is affliction, but by face and good muscle a woman may fight through, for a man knows when he meets his master, and having met her, he tempers his tyranny with humility—tempers his tyranny with humility.” Mercy loved high-sounding words.

“But you’ll temper me with something that isn’t humility,” interrupted Janet, tartly. “Get indoors, do.”

Mercy cast a reproachful look at Janet—a long, lingering, offended, lover-like look. Then, squaring her shoulders, she strode kitchenward, where she made a good deal of clatter for about an hour. Then she flicked at the cat viciously with a duster.

She fixed the cat with her eye. “They are a burden and a bitterness, the sowers of a whirlwind,” she muttered. “The unborn millions will be the ruin of the country.”

Even the cat had a limit when it came to Mercy’s ways, so she drew up her head, blinked disdainfully in Mercy’s condemining face, then turned majestically and left the room.

Janet had overhead. “Mercy’s jealous,” she thought to herself with a smile, and set about tidying things away in the adjoining room. The house had become a lot messier since Joan-John joined the family. As evidence: the sun-hat on the lobby peg, the doll on the sofa, a gleam of a bright-hued sash. A buckle of a tiny shoe in the work-basket, broken dolls’ tea-cups, a posey jammed into a jug, and a scarlet frock airing in the sunshine.

At times it all felt a bit much, so she sat down and plied a rapid needle, remembering a look on Tom’s face when their young princess had bounded in to kiss him, sitting on his knee, twining her arm about his neck, looking over at her mother half shyly, half coyly.

“Aren’t you getting to big to be nursed?” Janet had asked.

The child had replied, “This is my father, he belongs to me.”

Whenever she scolded Joan-John for romping, or rudeness, for shouting and screaming, for climbing trees or playing in mud, for saying “I won’t”, because that’s not what girls do, the child would give her a half-abashed, half-defiant glance, and continue on. She would not be obedient. She would not grow with the wisdom of a serpent and the harmlessness of a dove, just to please her parents.

Janet, more than Tom, understood that the world demands more from women: honestly, purity, loyalty and tenderness. A girl must dawn upon the world, “where the brook and river meet,” with sweet surprise in her eyes. She must be wise without experience to walk through rough and miry ways, unblemished and unhurt. And in the evening of her days, she must depart with grace and faith.

At present, Joan-John was failing miserably at all of this. She dearly liked having it out with her aggressors. She hit back with spontaneous and genuine relish.

Tom told Janet not to worry about it. Joan-John’s behaviour showed a manly spirit, and if only women would black each other’s eyes a bit more often, they wouldn’t have to blacken one another’s reputations with their tongues.

Janet looked doubtful and shook her head.

Mercy the housemaid bided her time.

If one waits long enough for an opportunity, it can pass one by. Opportunity is of no use when it comes after one has already changed their mind.

Joan-John’s tomboyism excited durable feelings in Mercy’s square breast. So when her chance of reproving arrived, she seized it then and there.

The cat regained its equanimity. Janet finished her sewing and went to watch the shearing.

Mercy, her face shining from her afternoon ablutions, sat with folded arms resting till it was time to prepare the evening meal. She was never more unapproachable than at this hour. Her freshly-starched dress seemed to bristle with the consciousness of its purity. On alert for warfare, the formidable Mercy glowered as she sat, at nothing in particular.

Presently, her quick ear caught the faintest creaking of the kitchen door. She turned with the agility of a cat watching for a mouse. A dripping object stood in the doorway. Two questioning eyes peered from under a tangle of damp hair.

Mercy rose slowly and squared herself, hands on hips.

“Hallo,” said a small voice, ingratiatingly.

“Hall-o!” responded a triumphant bass.

“I felled in,” apologised the treble. “I’ve got wet.”

“Wet,” queried Mercy sardonically.

The dripping head nodded emphatically.

Mercy strode forward, lifted the drenched object as she would a drowned kitten, and carried her into the bathroom. Here, she deposited Joan-John into the bath, stripped her down and treated her to a vigorous rubbing with a coarse towel. Then, still without a word, she robed the child in her night-dress and carried her to bed. At last she sat down, a threatening figure, by the bedside.

It was far too early for bed. Joan-John glanced lovingly at the open window, at the patch of sunlight on the floor, and then at her silent jailor.

“I was swimming a duck,” John-John tried to explain. “Such a dear wee duck. It wanted to go in. It’s mother is a hen, and couldn’t teach it.”

Mercy leaned forward, the afternoon light shining full on her hard-featured face, revealing with pitiless truth the lines that an unloved childhood and youth had drawn. Her look would have repelled most children.

“Say something,” Joan-John pleaded. “You frighten me.”

Mercy drew a deep breath. “Johnnie Jeffries.” She said the name ‘Johnnie’ with deep scorn. “Johnnie, Johnnie, Johnnie. I have never pined for children, but I wish that for one hour I could be your mother.”

“Why?” faltered the young person addressed, not detecting any maternal tenderness in Mercy’s glance.

“I’ve got my reasons,” replied Mercy, “and my hand itches to express ‘em.”

Joan-John tucked the bedclothes well round her, and changed tactics. “It wasn’t my best frock. I’ve got lots more,” she suggested anxiously.

Mercy never less personified her name. She rose in judgement. The unfettered and lawless one slunk a little lower under the bedclothes, but never for a moment removed her gaze.

“You’ve got lots more,” repeated Mercy, slowly. “Unto him that hath shall be given, there ain’t no limit to your privileges! When I was your age I had one frock—and only one—a solitary, only one—without any connections. A lone frock, dingy and thin, to say nothing of scragginess. I wore it week in and week out, and it were washed on Saturday nights to be clean on Sundays. I ran my errands in it, and did my devotions in it. It were turned top to bottom when the bottom got thin, and then turned bottom to top. When the colour faded on the right sides it were turned to the wrong. And when the wrong side grew shabby it were turned right side out again. When I growed out of it, the tuck were let out at the bottom. And when I growed out of that, my grandmother just put on a false hem. I hadn’t got no mother to pamper me. I hadn’t never a one.” Then Mercy gulped, as though trying to swallow the unfair distribution of things. “And when the wind blew, I knew it. No purple and fine linen covered me. The heat of summer got in through the holes, and the cold of winter likewise.”

Joan-John felt dazed, and slipped up a little from the bedclothes in sympathy. She blinked hard to meet Mercy’s glance with impersonal interest.

“Only one frock, and no mother. Didn’t you never have no father too?” she returned politely.

Mercy snorted so loudly that Joan-John went back down under the bedclothes, eyes and all. When her ears once more reached the surface she gathered the following:

“Goal cut his hanky-pankies short. No longer as a roaring lion might he seek whom he could devour. Prize your privileges, Miss Joan. Be an honour to the noble sect, and on’t rbing the hairs of that gentle lamb your mother with sorrow to the grave, for Satan finds some mischief still for idle hands to do. Thin of ‘how doth the little busy bee,’ and curtail your disposition to be wilful.”

Joan-John was greatly affected. She lay still for a full two minutes after Mercy left her, staring fixedly at the door. Then she sighed deeply and sat up. The discourse had left a distinct impression that Mercy’s father was a lion caged up somewhere, and that Satan didn’t like little girls. Her imagination adhered to the last conclusion and, pondering it with her chin between her hands, she brightened suddenly, and knelt up in bed. With the face and smile of a coquette cajoling her lover, she first looked up. Then, recollecting, she readjusted her attitude and looked down.

“Dear Satan,” she murmured sweetly. “The duck I falled in with was a very weeny one, and if you’ll please not find any more mischief for my idle hands to do, I’ll be a good girl. But I do like to do it.”

Feeling that she had set herself right with the powers of evil, she lay down with a satisfied sigh and went to sleep.

Tom stood on the threshold. He had been listening, arrested, to his child’s prayer. Now it had finished, he made his way thoughtfully downstairs to talk to Janet.

FATHER PUTS HIS FOOT DOWN

“I’ll do it!” Tom had made up his mind.

The evening meal was over, his big armchair drawn to the open window, where he smoked and ruminated.

“Do what?” enquired Janet, coming to a sudden stop in her journey across the room. She knew from the look on her husband’s face that he had come to some weighty decision.

“Yes, I’ll do it,” said Tom again, knocking the ashes from his pipe onto the windowsill.

Janet pointedly pushed the ashtray towards him, but Tom was too preoccupied to take the hint.

“I’ll put my foot down,” he declared.

Janet just looked at him, waiting for an explanation.

“On Johnnie,” Tom said. “On Joan-John Jefferies.”

Janet’s gentle heart took instant alarm. She sat on a low chair opposite, trying to appear unaware of the sleeping culprit’s latest prank. She smoothed the creases out of her own apron as though smoothing them out of Tom’s forehead.

“Why, bless me! Whatever has the child done now?” she asked. “Falling in the creek’s none so serious.”

“But praying to Satan is.” Tom said this with a tragic and dismal air.

“Satan? Who prays to Satan?”

“Joan-John Jefferies does,” said Tom, with a grave shake of his shaggy head. “I heard her with my own ears. And she looked pleased about it, too. ‘Keep my idle hands from mischief,’ says she, ‘but I like to do it’.”

Tom met Janet’s eyes. The humorous wrinkles round his took a deep indent. Janet sighed with relief and ventured a smile of her own.

“A harmless, innocent dear,” she murmured, then checked herself repentantly.

Tom straightened himself. “‘I like to do it!’ she said. Do you notice that, Mother?”

Janet flushed slightly, embarrassed. “It was very unbecoming. Still, it’s human nature. The child ain’t crafty with all her tricks. She owns that she likes mischief, which ain’t the way of most folks. Joan’s aggravating, but no sneak. Furthermore, she said she’d never fight—”

“What she said and what she’s got to do, have nothing to do with each other. Nothing,” interrupted Tom.

Janet did not like the look on Tom’s mouth. “You won’t be hard on a baby like that?” Tom looked like this when deciding to break a colt.

“Discipline is always hard. It’s a matter of more or less.”

This was scant comfort to Janet.

“Don’t make your face look like a diagram of angles, Mother,” Tom proceeded cheerfully. “The little one will be as happy as she can be when she gets used to it.”

Janet’s face did not acquiesce. She glanced at the unused rod in the chimney-corner.

“That ain’t my plan,” Tom said, following her gaze. “Moral persuasion is my plan. But come to some sort of understanding, me and Joan-John Jefferies must. When a Christian father hears his little one praying to Satan, it’s time to learn the young idea how to shoot, and where not to shoot, and what to shoot at.” Now he was mixing his metaphors. “A decent fear of Satan has drove many cowards into respectable living. In any case, I don’t hanker after him making a local habitation of my house.”

“You can’t teach a little mind more than it can take in,” said Janet.

“Leave her to me,” said Tom.

The little barbarian’s first lesson in the ways of wisdom took place on a scented and sunny morning, when she was at her least inclined for it. She had wandered beyond the homestead. All around her on the wide plains, idle sheep were grazing. Irresponsible larks carolled into pure space. Joan-John cared nothing about labour and pain. She was busy counting marguerites she had gathered. She was standing shoulder-high among them when Tom found her, singing a song about buttercups which she’d learned from her mother.

When Tom had delivered his lecture, she cried out impetuously and piteously, “I don’t like it, Father!”

Tom shook his head. “You’ll grow to it. I’ve heard the cry of the earth when the plough cuts into it, but I take no pity for the destruction of the grass, knowing wheat will grow in its stead. I’ve seen sheep tremble beneath the shears of the shearer. Work is a blessed thing. You’ll understand that in time. The Creator proclaimed it to the world and signed it with His royal decree, that work is good.”

Joan-John followed with her gaze the flight of a butterfly. Next, she lifted her gaze and caught sight of a lark.

“No,” she said, looking straight into the eyes of her father. “I don’t want to work. I want to play.”

“Ah, so we all do at first. But we learn better, by and by. You are getting a big girl, and ought to know things.”

“I don’t want to know many things,” said Joan-John Jefferies. She frowned, sat down on the grass and plucked more marguerites.

“Of course you do,” said Tom, drawing near. He sat with the child among the flowers. “Out he said,” pointing to the mysterious borderland, “is a world of cities—places beyond the most distant rim—”

“Ahh!” The child was interested now, and passionate for knowledge of the unknown.

“Read, my little maid. Read what has been and what is, and what is going to be. Be a scholar. I ain’t one myself, but that’s no fault of mine. ‘Whatsoever they hand findeth to do, do it with thy might.’ And I have done it. But it’s been rough work, dear maid. And while I have worked, I have wished. My work and my wishes haven’t gone the same road, not that that’s singular. But while I’ve been ploughing and planting, I’ve been longing for the knowledge of all that’s in the heaven above an on earth beneath, and in the waters under the earth. If you’d been a boy, Mother and me expected you to learn most things there was to learn, to become a power in the land. Being a girl, we hopes you’ll do the best you can.”

“Oh,” said Joan-John.

Then they went back silently, hand in hand, the man who craved knowledge and the child who wished to play.

The midday dinner hour was a busy time for Janet. She carved a whole side of mutton for the hungry farm-hands before she rested.

“Well?” she asked, when her husband had eaten and all but departed.

“I’ve done it,” he said, complacently.

Janet looked hard at him, then at the vanishing little red figure. “How did she take it?”

“Manfully,” said Tom.

Joan-John Jefferies trotted her favourite way to the plains, circuitously, by the gorge. There she paused, reconsidered, and made straight for the enclosures, where shearing was in progress. The great pens were packed with frightened sheep that looked from side to side, bleating piteously. Joan-John Jeffries stood straight as a flaming hollyhock, arms behind her back, and watched for the inevitable to come to pass. Her breath came hard and fast as shearers dragged the sheep from the pens and adroitly threw them in. She flushed while bright shears met in the soft fleece, which fell in white heaps about the terrified animals. She waited while several were shorn, branded and set free. Then, as though feeling the shame of the denuded, took herself off. The sight had extinguished her high spirits.

She lay down on the tussocks. Supporting her head with her hands, she looked steadily afar, seeking enlightenment. Her father had told her that, if she had been a boy, she would have known all things almost immediately. But since she was a girl, she would only get to know a few things, if she read a great deal.

There, beyond the shimmering grass, over the far line of blue, were the things her father of which her father spoke. He himself had seen those wonderful cities, with the people who did not milk cows and herd cattle or plough fields.

A lark carolled from the blue above, but Joan-John did not look at it. She was satisfied that the best things were that that she had never yet seen.

It would take a long time to read about them. She’d have to spend a lot of time on her spelling, and stay indoors. If she were a boy, she could go and see for herself. Still, she did have a boy’s name. Was she not entitled to some of a boy’s prerogatives?

Joan-John Jefferies as a good walker, and so the blue borderland came nearer. The intervening plains dwindled. Perhaps it was possible to reach those faraway places. She could walk there now and return on the morrow. The young sophist decided she could atone afterwards. At first she sighed, got up from the grass and determinedly set her back to Satan’s temptation. Presently she looked back, just a little glance, while moving in the right direction towards home. But, finding progression difficult with her feet moving in one direction with her head turned in another, she stopped again and turned. This time she set off at a full run, towards degeneracy.

Rosy-cheeked and panting, tingling with the delight of rebellion, Joan-John Jefferies came to a halt at last. With a little thrill at the suspicion, she turned to see whether, perchance, Satan was in the rear. But no, she saw only the gold-flooded tussocks and the house roof, too indistinct to impress its claims. So she journeyed between two infinities—the past and the future. Future possibilities thrilled her, but what lay behind was despised because it was familiar.

When she next came to a halt, the child was alone with the universe. All landmarks were obliterated, except the western mountain range. The space was speechless—no sound came yet from the city. Joan-John Jefferies felt no fear, only a little wonder that the world was so large. She kept up a little jog-trot, her footfalls falling noiselessly upon the turf. But when she had grown weary, she was astonished to find the margin of earth and sky no nearer, only more misty and indistinct. She stood alone in the unbroken silence and mysterious shadow, and sighed when the last glow of sunlight faded in the West.

Her own sigh startled her. She thought someone else was standing near her.

When she had satisfied herself that this was not so, she regretted her isolation.

At home, Mercy would be making tea. Mother would be waiting for Father to put on his slippers before pouring it out. How nice some tea would be. She was very thirsty. She wiped a tear from each eye with her handkerchief—Joan-John Jefferies was dainty in her ways—then, with a fresh spurt of determination, she went on again.

With sunset there came from the east a heavy, damp mist, which brought a cold breath from the sea. This deepened presently to a drizzle, and Joan-John’s curls clung damply to her forehead, her eyelashes moist and vision blurred. At last she could see no farther than her own inquisitive nose.

“I’m not crying,” she said aloud. “It’s the rain blowing into my eyes.”

But her assertion sounded so bold, uttered in such appalling silence and darkness, that it frightened her. She said no more, not even to herself, but crouched down on the wet tussocks.

She strained her eyes through the gloom for the lights of the city. Suddenly she gave a little low ecstatic cry. There was a light, a red, glowing light that burned out of the darkness. It disappeared, reappeared, and broadened to a flash. It swept the plains like a search-light. Joan-John’s eyes ached beholding it. She jumped to her feet, startled by a long, loud, but tremulous, “Coo-ee!”

Her heart thumped in her ears, so loud she could not hear her own reply. Then the gladdening light flashed nearer. Next, the music of hoof-beats upon turf. Another flash revealed Father on his old cob. He held a lantern in his left hand, above his head. He wore neither leggings nor topcoat, for he had ridden forth hurriedly, but over the saddle hunt a thick grey shawl.

For a moment the lantern rays shone on Joan-John, with outstretched arms and a scared, uplifted face, and on Father’s drawn and furrowed cheeks. His mouth was set as if he had ridden in the teeth of death. He lowered the lantern with the catch of a breath, something like a sob. He set the lantern upon the ground, bent one knee and carefully wrapped the shawl about Joan-John. Then he extinguished the light, remounted, set the child before him, and without a word turned the horse’s head. His strong, encircling arm trembled, and closed round the soft body with a tightening grip.

Presently he muttered to himself. “Seven years last autumn I rode this same way to receive her. Oh, give thanks unto the Lord, for He is gracious, and His mercy endureth forever.”

The windows of the farmhouse shone like a beacon. Torches and lanterns flared in the mist, casting grotesque and gigantic shadows of men and women on the walls of the barns, appearing there for a moment with mocking gestures, then disappearing to be seen later among the dark trees of the bush.

Mercy, with pale cheeks, believed she knew what had happened. She peered with frightened eyes into the gorge, flashing a lantern across its gleaming waters, craning her neck and starting at every object that obstructed the stream.

At the boundary gate, Janet stepped out of the darkness. She had listened to the approaching hoof-beats with a heavy, choking heart. Tom reined in with a jerk. He could not see his wife’s face, but he discerned it with his mind’s eye. She put out both hands and touched the unresisting bundle in her husband’s arm.

“Twice given,” she whispered hoarsely. Then she cried gladly, “Twice given!”

Tom dismounted. Janet clutched at the bundle, and made to carry her seven-year-old into the house. She turned at the threshold, and in front of all the eager faces, kissed “the master” on the mouth.

The young prodigal had been warmly bathed, robed in white flannel, fed and cried over by her mother and blessed for being alive by Mercy, who shook her head the next moment and declared, without explanation, that it was “disheartling”. Now she stood on the white sheepskin rug in front of the fire, directing occasional side-glances at Tom, who sat in his chair smoking, not seeming to notice his anxious child who stood before him.

Janet did not attempt to rouse him. He roused presently of his own accord, knocked the ashes out of his pipe, put it carefully away, then looked at Joan-John steadily.

“Speak up, young maid and answer fair. Did you, or did you not, mean to run away from me and Mother?”

Joan-John straightened herself and slipped her arms behind, like she always did when she meant business. Father and child stared at each other with their grey eyes.

“Why, Father,” besought Janet, hovering nearby in trepidation. “Surely you’re glad enough to have her back.”

“Hush up,” said Tom, without a flinch in his gaze.

So Janet hushed up, and Joan-John gave a nod.

“You meant to run away? Speak. Don’t nod your head like a pony.”

“Of course she didn’t,” said Janet, who was afraid she did exactly mean to.

“Hush up!” commanded Tom.

Joan-John rubbed one bare, swollen foot against the other, lifted one damaged leg and glanced at it, then met her father’s eyes again.

“I runned away,” she said.

Janet gave a startled cry, and sank into her rocker.

“Mother, I’m surprised at you!” scolded Tom. “When I ask you to hush up, hush up!”

He had risen from his chair, and stood with his legs apart and his hands thrust into his pockets. He looked from his great height down upon his white-robed wife of five foot two, as if she were some unknown species of duckling—seriously, and with great concern. He felt all at sea.

To Joan-John he said, “You ran away of your own free will and accord from home? Away from me and Mother?”

“Yes, Farver.”

“Why?”

“To see the world,” said the young explorer, with the intonation of a Cockney.

“The dear innocent,” said Janet from the rocker.

“Look, Mother,” said Tom, so quietly that she knew he meant it. “If you won’t hush up, you and me will have a difference.” Then he turned back to his child. “So. You were off to see the world, were you. Do you think the world wanted to see you?”

Joan-John rubbed her wounded foot again, then shook her head.

“The world ain’t kind to innocents,” said Tom. “Home’s the place for them. Say you wont run away no more. On the honour of John Jefferies—gentleman. Say that you’re sorry you ever ran away at all.”

Joan-John stood on both feet, tilted on her toes, flushed, but said nothing. Tom waited. Still no answer. He looked at the road. A deep groan of smothered anguish escaped Janet, and Joan-John burst out: “No, no, Farver! No, no! I ain’t sorry. Cause I liked to do it. I won’t do it no more, but I ain’t sorry I did it!”

Tom’s face softened while Joan-John’s quivered. As for Janet, her face was invisible, hidden behind her apron.

“Do you mean,” asked Tom, as though he wanted to know, “that you’re sorry that you can’t be sorry?”

“No,” said the straightforward Joan-John. “I ain’t sorry cause I ain’t sorry. I’m sorry cause I must stay at home and read.”

“In that case,” said Father, stooping to lift her in his arms, “you come to bed without kissing your mother, and stay there without her till you ar. I can’t have no bad little maids in my house, that’d sooner run away and leave her mother than learn her book.”

Tom left the child unkissed, but waited on the outside of her bedroom door. There he waited and listened, as little Joan-John stifled her sobs. Every sob stabbed him.

“It’s called discipline, dearie,” he whispered.

“I’ll be good now Farver,” said the child.

When Tom trusted himself to enter her room, Joan-John lay quietly on the soft pillows sleeping. Long-drawn, spasmodic sighs occasionally convuled her soft, round throat. Her face was wet with tears. One small cheek lay on the forehead of the battered wooden doll he had brought home that first night he forgot a present for Janet. He gazed til his own breast heaved.

Tom and Janet had been in bed about on hour, each pretending to sleep, when a knock came at their door, low down.

“I’m good now,” came the voice from a short, white-robed figure.

“You shouldn’t leave your bed. You’ll catch your death, my lamb,” said Janet.

“Climb up,” said Tom. “There’s room here between.”

UNDER THE PLOUGH

From that day forward, Joan-John did as she was told. She read and read and read. She took to learning like a “duck to water”, as Janet put it.

As for Tom, he was determined to set a good example, or, to keep up. He was frequently seen under the shadow of a hayrick, studying a dictionary. A pocket encyclopaedia bulged from his coat while he rode round his boundaries. He was even heard reciting Wordsworth, with one eye on the threshing machine.

Before long, Joan-John had noticed her father trying to sound scholarly, adding aitches to his words where none were before, and correcting his ‘ink’s to ‘ings’. Her manner grew slightly patronising. But Sundays counteracted this dynamic, for on Sunday Father preached.

Tom held Sunday service in the barn. This barn was “an upper chamber,” and reached from the farmyard by an awkward flight of wooden steps. It was a long, cool building, redolent of wheat and chaff, sacks of which made comfortable pews. The dairies were near and, in summer, scents of clover and new milk wafted through the open door, pastoral details which illustrated Tom’s sermons very nicely.

Standing at his desk—constructed from packing cases—in black cloth and white linen, his massive head thrown back, his bronzed, rugged face glowing with enthusiasm, he might have roused spiritual energy in a larger and more callous band than the farm men and women who made his flock. Tom had the orator’s art, though not the scholar’s knowledge. He knew by instinct just how to touch the matter in hand, and with the poet’s gift, raised it on high for contemplation.

Janet listened with one eye on the poultry, the other on Joan-John, who had usurped the place of the second John the Baptist, and sat during these meetings on a flour-barrel, looking capable of every sweet and heavenly emotion. Her eyes wandered during prayers, but the moment her father’s discourse commenced, he had her attention. Father and child were intellectual companions. Whenever he made a point, her cheeks would flush and her eyes brighten. Once when he wanted a word, she called it out to him unconsciously.

When Monday came, Joan-John would read the Scriptures, while critically incorporating what her father had said on the Sunday.

Janet was not entirely happy with this development. She began to wish that her daughter would love her parents more, and admire words less. Janet was indeed jealous of the books, and strove to interest Joan-John in the kitchen. But Joan-John turned her mother gently away from cooking and also from sewing. She turned with scorn from Mercy and the dairy. Instead, she converted the attic into a picture-gallery and study. There she kept every old newspaper and her father’s books, reading them indiscriminately.

This attic ran from east to west of the house, with a window at each end. The east window gave an extensive view of the sheep plains. From this end, Joan-John watched the sun rise from the unknown world. The west saw it set behind mysterious mountains.

Mercy secretly gloated that Janet and her child “were not what you’d call wrapped up in one another,” and said to the cat, “”It all comes with discontentment with the ways of Providence.”

Safe in the attic to arrange her own day as she pleased, Joan-John took pleasure in words. She would roll the “r’s” off her tongue with much confidence as she read—always aloud. She did not require company to hear her, although it was a bit of a waste not to have her performances appreciated.

Out in the open air she caught the spirit of the poets. She read glint of sunlight and grey of twilight into a line. She caught the tinkle and rush of water. On winter evenings, to cajole her father away from the harmonium, Joan-John read aloud. And if her mother’s tears refused to flow, and if her father stared hard into space, she knew there was something wrong with the reading. So she’d try it again in the attic.

“Joan-John Jefferies must go to Girton [Girton College was the first women’s college at Cambridge in England, established in 1869. Christchurch had Canterbury College (now Canterbury University), which was set up according to the Oxbridge model, except women were admitted. The first woman to graduate was Hellen Connon, in 1880. She went on to earn an MA with first class honours in English and Latin.

Joan-John’s parents are from England, and they are using “Girton” as a shorthand to mean higher education for women.],” announced Tom, when Joan-John was eleven.

For the first time in her life Janet disliked her husband.

“What do we want with a Girton girl, at a farm?” she asked him. “What we need is a homely person who knows how to make pies and look after the linen. A house and a husband and a baby gives a woman more instruction than all the books in the world. And there ain’t no Girton nearer than Christchurch,” she added, “more than a day’s journey by coach. And what will the maid do so far from home? I’ve heard of them Girton women! They’ve a deal of knowledge about the bowels of the earth, but are surprised if heavy pastry gives a child the stomach-ache. What does a bonny lass need to know about the orbit of the stars, so long as she can regulate the course of her own household?”

“Joan-John Jefferies is a gentleman,” said Tom. “She’ll do us credit. Whatever her hand findeth to do, she’ll do it manfully.”

“I don’t believe you’ve got over the notion that she’s a boy,” retorted Janet. “She’s a woman child, dear. And sooner or later she’ll discover to which half of creation she belongs. I’d have been proud of a man child, if he’d been a he, but being a she, I’d take shame of it. It’s all the fault of that blessed christening.”

SOWING SEED

1890

From their high tower the cathedral bells rang out sweetly over Christchurch—city of the plains. The Christchurch cathedral stood at its centre, in the commercial square. This was given over to the quiet of evening. Broad paved streets and tall stone buildings looked ghostly in the twilight, for as yet the street lamps were unlighted. Amid the greyness, the cathedral, lit for service, stood out boldly from the dun canvas of its enclosure. Its open door and coloured windows glowed ruddily. The great cross on the spire, the domes and spires of many suburban churches, winked at one another irreverently in the after-sunset beams. The high tree-tops still shimmered, but the Avon River that embraced the city flowed black and steely beneath overhanging willows. And far beyond the environing plains were grey, except where cut by foam-crested torrents or lit by the flashing lamps of the incoming express which, tearing over their expanse, ripped through their silence with piercing shrieks.

Christchurch was the commercial centre of New Zealand’s finest agricultural district. The city retained from its foundation a distinctly English educational and ecclesiastical atmosphere. At the West End were stately and picturesque colleges. Sylvan residences of church dignitaries and professors fringed the river near the famous museum and parks. Except for the soughing wind among great green branches, and the deep-toned voice of a turret clock, the city was quiet.

Girton College stood facing the river where an oak avenue came to an end and became a riverside path. The building was a rambling old cottage with dormer windows and verandas. The college proper, connected by a covered way, was built on a strictly scientific and hygienic plan. The house was made to be cosy. It stood in a large overgrown garden, the porch so covered in vines that, except for a glowing red lamp, it would have been hard to find the door, with its burnished brass plate inscription:

“G. Goodyear, M.A., Principal.”

Miss Goodyear was sitting in her study, in a Russian-leather armchair, resting. The walls of the room were lined with bookcases. A thick carpet of rich crimson overlaid the floor. Curtains of the same hue hung at the windows, the lower panes of which were hand-painted. Panels of the door showed the same design of hand-painted flowers. A bear-skin rug was spread before the gas stove on the tiled hearth. Another was thrown over a low couch. Several deep-seated chairs were scattered about. A few exquisite watercolour paintings stood on ivory easles on the mantel-board, with a few photographs. Near the hearth was Miss Goodyear’ss chair and a handsome carved oak reading-table. On this, a green-shaded reading-lamp was burning. A porcelain vase, filled with red and white roses, stood near the lamp.

Gertrude Goodyear rose and, with an easy, slow movement, crossed to the bookcases, touching a volume here and there with the light, lingering touch of a mother caressing her baby’s hair. She was dressed in a black garment—a cross between academic robe and tea-gown. Her age was impossible to tell. When she smiled she appeared little older than a girl, but right now her pale face was impassive, her mouth firmly closed, and three lines of concentration showed between her dark, straight brows. She looked thirty at least. She stood tall, slender and square. Her chief beauty was her curly blonde-brown hair, cut short like a boy’s. Her eyes were also handsome, but for the quizzical glance that shot from their blue-grey depths. Her neck, hair and ears were so truly feminine that they seemed at variance with the square shoulders and the film lines of the chin and lips, and the lordly air that fought with charm and grace. In one light she was seductive and invited caresses, the next her manner signified, “I pray you have me excused.”

Miss Goodyear created much amusement among her set by her satires and caricatures of the women of fashion—the purse-proud and commonplace women who darned the stockings and had babies. Of men, she had absolutely nothing to say. Men were invited—collectively—to her lectures and homes, but never admitted individually to her domestic hearth. Never, unless he changed to be a lion or a hero. There might have been a love episode—she never said. She made no complaint whatsoever. She had won her woman’s reward and she smiled her inscrutable smile.

The sound of cab wheels caused Miss Goodyear to lift her head expectantly. Presently the brass knocker shook the door and echoed throughout the house.

Miss Goodyear turned on the electric light[ Electric home lighting was very new, and this is why it is mentioned. Miss Goodyear represents the modern woman, and everything about her is also modern. Electricity was expensive at this time in history. Gas was cheaper. Most people were still using lamps and candles, and other forms of personal, portable light. Once electricity was used, light was no longer either personal or portable.], dispelling the partial darkness of the room.

“Mr, Mrs and Miss Jefferies,” announced the maid.

Next, Tom, Janet and their daughter Joan-John were ushered in.

The brilliant light dazzled Tom’s eyes. The three from Ōtira Gorge Farm new to electric lighting, a luxury which had yet to reach rural areas. Shading his squinting eyes with one hand, as though from the rays of the rising sun, he discerned a lady in the radiance. He bowed with the gravity of a magistrate. Then, overtaken by a sudden impulse, he thrusth out his hand. Miss Goodyear let her slender, strong hand rest for a moment in the large, brown palm. Then she advanced to greet Janet.

With simple and undisguised satisfaction, Tom undertook the introductions. “Miss G. Goodyear—my wife, Mrs Thomas Jefferies. And this is Joan-John Jefferies of Ōtira Gorge Farm, Canterbury.”

Miss Goodyear bowed. It was a moment before she raised her head. When she did so, the sad, grey eyes were sparkling.

“I expected you by tonight’s express,” she said quietly, drawing forward a chair for Janet, and at the same time taking in every detail of the Quakerish figure.

Tom refused a seat. He stood on the hearthrug, demanding attention. His grey tweed suit smelled of new-mown hay. The night was warm, but he wore a knitted comforter[ a long, wide scarf or a lap robe. See it mentioned in A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens in reference to Bob Cratchit, the overworked, underpaid clerk of Scrooge: “…the clerk, with the long ends of his white comforter dangling below his waist (for he boasted no greatcoat)…”] of white wool, because Janet distrusted the air of the cities[ This is an example of miasma theory. It was observed that cities were more likely to kill you of some respiratory disease. Now we know that viruses spread where there is a denser population. But at this time, it was thought there was something in the air. It didn’t help that the air in cities was often smelly, due to inadequate sewerage and rubbish collection or, in the early days of Christchurch, the smoke from woodfires.]. The fringed ends of this long, wide scarf hung almost to the carpet. His massive grey head was lifted proudly, as though conscious of his important part in the bestowal of such a pupil as Joan-John upon the learned lady, who was to “rub the rust off” her. He smiled benignly, as a generous-hearted person who bestows a favour.

Miss Goodyear understood that she was the grateful recipient in this situation. Instead, gratitude should be theirs. After all, she had renounced for life sexual and maternal joys, ease and peace, to train other people’s children.

Tom never found himself embarrassed in any circumstances, and so he talked. He played his simple part honestly, and told Miss Goodyear about his daughter—yet another uncultivated mind brought to her for culture.

Later, the parents would return for their child and boast of her ability and move on. Miss Goodyear herself would be forsaken and forgotten.

Best not to think of such embittering things. Her cause was woman’s cause. Every fresh thinker among women helped forward their emancipation[ New Zealand women were granted the right to vote in September 1893. This meant New Zealand was the first self-governing country in the world where all woman citizens had the right to vote in parliamentary elections. They voted for the first time that November.].

Meanwhile, Janet sat watching the grave face of Miss Gertrude Goodyear and decided: No, she didn’t like her much. She was neither a natural woman, nor domestic. Then her eyes fell upon a volume on the bookshelves. “Bacon.” Another was called “Lamb”. [ Janet reads the author names and assumes they are cooking books, when she is looking at the works of Francis Bacon (philosopher) and Charles Lamb (essayist, critic, poet and playwright).]She tried her best to readjust her first impression. But, she understood this woman was destined to be her rival in the admiration of her own child, for Joan-John looked interested in this woman. Her glance had travelled slowly from the curling head and daintily proportioned figure back to the piquant, sun-tinted face.

Miss Goodyear, in greeting Joan-John, exclaimed an enigmatic, “Ah!” and stretched out her hand with a quick movement.

Joan-John placed her small palm in it, and glanced up into Miss Goodyear’s gaze.

“Make a scholard of her, ma’am, make a scholard of her!” said Tom.

Miss Goodyear was very tired. She wished they would go, but she remained courteous and attentive.

Tom glanced at Janet, who was struggling to keep her face calm for the parting. He shifted from one foot to the other, twirling his wideawake in his hands. Then he said, with a deprecating glance, “With your permission, we will now commit the stranger into safe keeping.”

Miss Goodyear bowed once again. She gave the great, rough man credit for a pretty compliment. Then an unexpected thing occurred. The father drew the little girl into his encircling arms and knelt, Janet beside him.

Miss Goodyear, embarrassed, stood with one hand resting lightly upon the reading-desk. She wrestled for a moment with a feeling of vexation, until realising the trio were at their devotions. Her embarrassment changed to attention when the man’s voice faltered:

“When we are farthest from home, we are most akin to Thee, for Thou wert a wanderer, O Son of man. Silence an’ solitude echo Thy sorrow, for Thou didst dwell in the wilderness.”

Quite eloquent, thought Miss Goodyear.

And when she bowed Tom out there was a subtle change in her demeanour. Respect. She stood patiently by while the farewells were said.

Tom cleared his throat, for it had grown suddenly hoarse. “Little maid,” he said, “be a gentleman.”

“I shan’t tuck you in tonight,” said Janet, tremulously. “Come, Father.”

Tom’s voice was loud all the way to the gate, and loud for some distance down the quiet street.

When it had died away, Miss Goodyear returned to the study.

Joan had sunk into an easy-chair, and was leaning back among the cushions, brows puckered, lips compressed. She said nothing.

Miss Goodyear glanced at the small, forlorn-looking figure then crossed to Joan-John’s chair. She noted pale cheeks and dark circles under closed eyes.

“You don’t cry,” she said, a little wonderingly.

Joan’s large eyes opened.

The two stared at one another.

“Do you cry?” asked the small girl, in a toneless voice.

Miss Goodyear was surprised once more tonight. “I do—occasionally,” she admitted, as to an equal.

“So do I,” said Joan-John, sitting bolt upright. “But not when I get something I want very much.”

The perplexed expression deepened upon Miss Goodyear’s face.

“This,” explained Joan-John, waving towards the shelves.

“Ah! I understand,” rejoined Miss Goodyear with spontaneous interest. She bent forward from the waist and asked eagerly, and yet with slight hesitation, “You find the exchange of home and parents… for books… easy?”

“No,” thundered Joan-John. “I do not. But one must give something always for the thing one wants.”

Miss Goodyear turned off the electric light and sat down near the reading-table. Leaning her chin upon one hand, she looked steadily at her new pupil.

“Who told you that?” she asked.

“I just know,” said Joan. “To gather small fruit, one must be pricked. To get at the large fruit, one must climb.”

Miss Goodyear slowly nodded, still with her hand supporting her chin, still looking intently at Joan.

“You’re right,” she said presently, “and if you want to achieve, take no notice of outside distractions and hindrances. Many see the goal from afar, but it is in the getting there that proves the individual. Thousands start, only one here and there reaches the goal. Genius consists not so much in the strong pull as in the long pull.”

Her eyes were not looking at Joan-John now, but through her and far off, seeing things the child had not yet seen.

“Almost everyone is capable of a sudden rousing—a big effort either for honour or affection, or for ambition’s sake. But, after the first glamour and enthusiasm have passed, the long, silent pull in cold, common sense is a rarer thing.”

Miss Goodyear meditated for a time, seeming to forget the child, who sat and watched her, half-faint with hunger and also homesickness, and a strange new sense of fascination.

“Those who reach the ultimate goal leave much good company behind,” continued Miss Goodyear in a dreamy trance. Then, suddenly rousing, she became aware of a small, pale, pained face. “Is anything the matter?” she asked quickly.

“I think I should like my supper and then to go to bed,” said Joan, with trembling lips.

Miss Goodyear rose hurriedly and rang the bell. “Yes, of course. I beg your pardon. I forgot. I am sometimes absent-minded and preoccupied, I fear. My pupils return to their homes after we have finished our day’s work. Our association is purely mental. Bring supper,” she said to the maid. Then, turning to Joan-John, she asked, “What did they give you at home for supper? Your mother seemed anxious about your physical well-being. The thing is, I’ve never had a girl—a child—living with me before. What do you usually eat?”

“Oh, anything,” answered Joan-John, wearily. “Chicken or duck, or ham, or things.”

Miss Goodyear looked relieved. “Yes, thanks, Ann,” she said to the girl, who stood respectfully awaiting her orders. “The chicken… and things.”

When the tray came, Miss Goodyear waited upon Joan almost humbly, and spoke only once during the meal.

“Ah. Fresh bread was prohibited[ In the early 1800s, governments, particularly in Britain, enacted bans on the sale of fresh bread to conserve resources during times of wheat shortage, as stale bread was seen as more filling and would increase a loaf’s stomach-filling capacity. The Making of Bread, etc. Act 1800 in Britain is an example of this, following the poor wheat harvest of 1799. This act required bakers to hold loaves for 24 hours before selling them to ensure the bread was less appealing—bread was also made only of wholemeal flour—and would thus be consumed more slowly and efficiently. This act was very unpopular and only lasted a few months.

But the idea that fresh bread was an unnecessary luxury while old bread was more filling continued through the century, for example with parents who thought their children would turn out better if they were not “spoiled” by things such as fresh bread.], I remember,” she said, putting away the new roll, and cutting from a stale loaf. Then she said, “Is it your usual practice to engage in devotional exercise before retiring? I mean—do you pray?”

Joan-John nodded.

Miss Goodyear looked anxious. “I think,” she said, “I will limit my instruction—supervision—to intellectual and material interpretation. The spiritual is, I fear, somewhat out of my sphere.”

Joan-John looked in nowise distressed, and followed Miss Goodyear upstairs.

THE GREEN BLADE

Miss Goodyear’s absent-mindedness was not a chronic issue, but due to her staying awake into the night. As the head of her school she was “all there,” as Janet put it. She had no time for incompetence and indolence, and roused in her students a passion for achievement.

Having fought her way up from a life of poverty herself, Miss Goodyear believed labour was the only justification for a person’s existence. Failure was a sadder word to her than death. She had power, influence and admiration. All sorts of people found her useful. But, she had no love. She had roused passion in more than one man—the passion to subdue. No man had ever longed to serve her. But everyone around Miss Goodyear valued her approval and praise. She lavished motherly levels of care on other people’s children.

The chief hall of the college was lofty and light. At one end was a small stage, and also Miss Goodyear’s desk.

On the morning after Joan’s arrival, Miss Goodyear stood at this desk. Sunlight glowed over her shining hair and sombre gown.

“Everyone, be sure to make Joan welcome,” she said.

But the teacher was uncertain where to place this country-bred but pale-faced pupil in the sailor suit of serge. Joan-John was interested and excited, wholly unembarrassed to be the centre of attention. She simply waited for the next thing to happen. It was the morning for literature. With some trepidation, Miss Goodyear placed a copy of Hood’s poems in the new girl’s hands, open at “Eugene Aram,” Thomas Hood’s ballad about the 18th century English scholar, school-master and convicted murderer.

Joan-John scanned the page quickly, then began to read.

As she read, a deep silence fell upon the room. The other students were at first surprised, then became quickly interested. Miss Goodyear, too, soon forgot who was reading, and became engaged in the subject matter.

When Joan-John finished the reading, there was a moment’s silence, then a storm, as of hail, made by the clapping of hands. Miss Goodyear stepped from her pedestal and shook hands with the child.

After that day she tasked Joan severely. At home Joan had been spoilt. Her wishes had hitherto been consulted, but not any more. Miss Goodyear kept her well away from poetry and allowed the child only the hard, dry mechanism of fact. On the farm she had been immersed in the sensuous and aesthetic, but here her days were so many geometrical figures. The child’s performance must be exact, finished, clear. She was taught to reconcile drudgery with intellectual freedom.

But when Miss Goodyear started to disentangle Joan-John from her educational system, realising her as an individual, Miss Goodyear’s life improved as a result. Her lonely rooms began to brighten. She remembered old games and surprised herself with sudden bursts of laughter. She found that not every hour had to be filled with accomplishing her duties. She could allow herself to relax.

At first she fought with this feeling.

Miss Goodyear had always held herself to impartiality and justice, but once or twice of late, the Principal of Girton College had detected herself hoping for honours for Joan-John. The discovery appalled her. She concluded she must be overworked, and losing control of her nerves. But, she had grown fond of the girl.

In front of the other students, the most rigorous discipline was kept no. Miss Goodyear permitted no familiarity. But inside the house, the diligent and exemplary pupil whistled, and Miss Goodyear called her “Johnnie.”

Janet found her out.

“It isn’t often that I express an opinion of my own,” she said to Tom sarcastically, “but I really do think that when a woman has mastered everything there is to master in the way of scholarship, and thinks that babies are only a special provision of Providence for them to teach, it’s a little ridiculous to fall in love with another woman’s child.”

Miss Goodyear suspected that Janet had found out her secret. She tried to placate her. But Janet held the whip. Possession was nine points of the law, and she reminded Miss Goodyear that Joan was hers, belonged by right to her, inalienably.

“When the maid comes home,” she would say, with an expression that hardened her face.

Once, after one of these scenes, Joan-John sat looking wistfully into the fire. Three years had passed since her first occupation of that chair. But Miss Goodyear could never tell whether she cared to be with her or not. There had been inconsistency in her dealings with her girl. She had taught the superiority of the intellect over the emotions.

“I suppose you’ll be glad when Girton is a phase of the past,” Miss Goodyear said to the girl.

“Not at all,” answered Joan-John calmly, putting her head on one side, bird-like.

Miss Goodyear felt the indignity of her position. She turned away to her books.

“In fact, I hope you will let me stay on with you,” said Joan, gently.