First, what is autofiction? Others have written eloquently about this, e.g. Adele Annesi at Jane Friedman’s blog.

Autofiction is a little similar to free indirect discourse but is suited to stories which deal with themes around truth. Claus Elholm Andersen talks about autofictionalisation at the High Theory Podcast. The following draws from that interview with extra notes from further reading.

The only way you can write the truth is to assume that what you set down will never be read.

Margaret Atwood

WHAT IS AUTOFICTION?

A subgenre of the novel that involves a blurring between fiction and reality that would be highly problematic in straight autobiography of an important person (e.g. a president).

In essence, autofiction is a story in which main character, narrator and author all have the same name. This person/character claims to be telling the truth.

FEATURES OF AUTOFICTION

Whereas straight autobiography is written as if non-fiction, autofiction authors make use of techniques and devices we typically associate with fiction e.g.

- Metafictive devices (Any technique which reminds readers they are reading a story as outside observers)

- Fragmentation (Fragmentation is a literary practice of the postmodern era. To fragment is to disintegrate, which is what the writers did to their themes and narratives.)

- Metatextuality (A form of intertextual discourse in which one text makes critical commentary on itself or another text. This concept is related to Gérard Genette’s concept of transtextuality in which a text changes or expands on the content of another text.)

- Hybridity (Refers to any mixing of East and Western culture. Within colonial and Postcolonial literature, it most commonly refers to colonial subjects from Asia or Africa who have found a balance between Eastern and Western cultural attributes.)

A BRIEF HISTORY OF AUTOFICTION

The term autofiction has a long history, especially in France. (The word is at least 40 years old.) But after the financial crisis of 2008, authors around the world started making use of autofictive techniques.

Why?

To create a sense of authenticity. After the financial crisis, people felt lied to en masse.

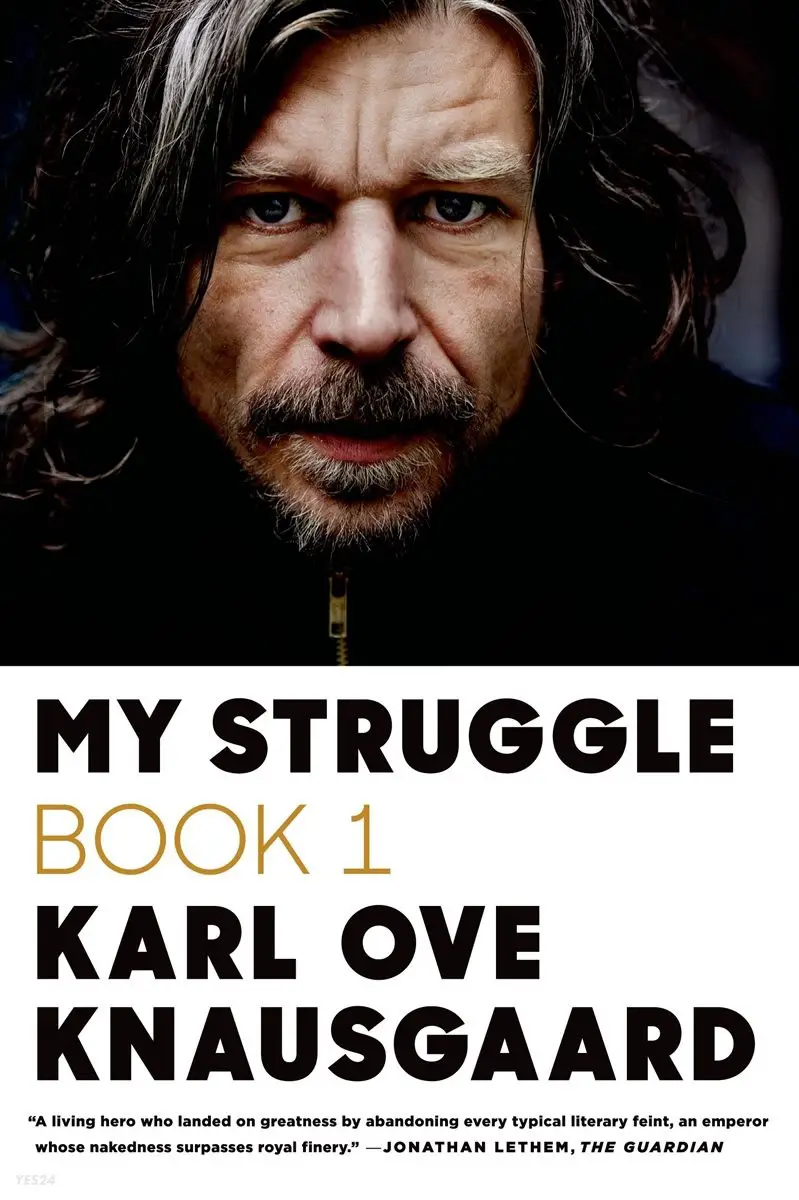

In 2013 My Struggle by Norwegian author Karl Ove Knausgaard was translated into English.

A New York Times bestseller, My Struggle: Book 1 introduces American readers to the audacious, addictive, and profoundly surprising international literary sensation that is the provocative and brilliant six-volume autobiographical novel by Karl Ove Knausgaard.

It has already been anointed a Proustian masterpiece and is the rare work of dazzling literary originality that is intensely, irresistibly readable. Unafraid of the big issues-death, love, art, fear-and yet committed to the intimate details of life as it is lived, My Struggle is an essential work of contemporary literature.

MARKETING COPY

This book is thought to be the breakthrough novel which introduced autofiction to a wider international audience.

Some critics complain about “the Knausgaarding of Literature” — the trend of plotless, “boring” novels — which speaks to its influence.

SOCIOECONOMIC UNDERPINNINGS

The financial crisis of 2008 revealed an entire financial system built on fiction. We started hearing about this thing called ‘derivatives’ for the first time, alongside other financial instruments, all built on fictional money. There may be a correlation between that realisation and a tendency for readers to turn to reality — or the appearance of reality — in their reading material. We crave realness, truth and the concrete.

Another interesting point: Claus Andersen only ever meets Knausgaard fans who will only read the physical books, avoiding eBooks.

#METOO AS ‘SEXUAL FINANCIAL CRISIS’

“The truth might be hard to bring to light, but that didn’t mean it didn’t exist, because it did exist: fixed in its moment, unalterable, and certainly not a matter of ‘belief.’ “

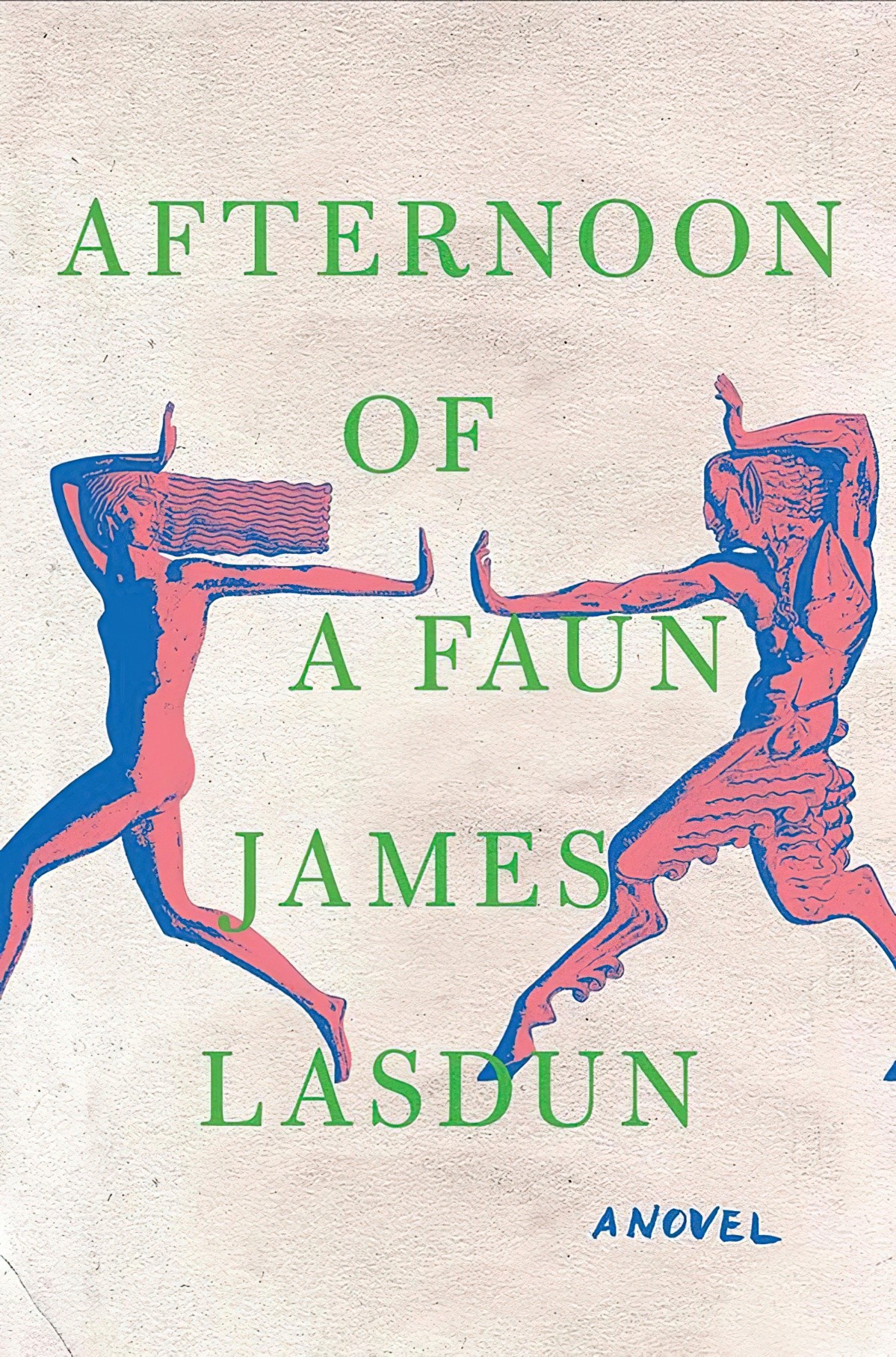

When an old flame accuses him of sexual assault in her memoir, expat English journalist Marco Rosedale is brought rapidly and inexorably to the brink of ruin. His reputation and livelihood at stake, Marco confides in a close friend, who finds himself caught between the obligations of friendship and an increasingly urgent desire to uncover the truth. This unnamed friend is drawn, magnetized, into the orbit of the woman at the center of the accusation—and finds his position as the safely detached narrator turning into something more dangerous. Soon, the question of his own complicity becomes impossible to avoid.

Set during the months leading up to Donald Trump’s election, with detours into the 1970s, this propulsive novel investigates the very meaning of truth at a time when it feels increasingly malleable. An atmospheric and unsettling drama from a novelist acclaimed as “the literary descendent of Dostoevsky and Patricia Highsmith” (Boston Globe), Afternoon of a Faun combines a sharply observed study of our shifting social mores with a meditation on what makes us believe, or disbelieve, the stories people tell about themselves.

Katy Waldman at The New Yorker pinpoints autofictive elements in a 2019 novel Afternoon of a Faun by James Lasdun, a so-called post #MeToo novel:

…an objective truth does exist here, and, finally, Lasdun reveals it. The shock of this moment owes to how tightly the book’s psychological mechanisms are wound. It also owes to “Faun’s” autofictional elements. Biographical echoes invite us to read the narrator—and, to a lesser extent, his foil, Marco—as alternative-reality versions of Lasdun. At times, “Faun” feels squarely in the space of Karl Ove Knausgaard, Rachel Cusk, Sheila Heti, and others. But here, Lasdun marries autofiction to the more obviously stylized genre of the psychological thriller, deploying cliff-hangers and the trope of the unreliable narrator. This is a neat idea: autofictional garnishes on a suspense novel can create a sense of claustrophobia, or become an eerie extra quotient of human consciousness, as if another pair of eyes were watching.

Katy Waldman at The New Yorker

If the financial crisis shocked many people into the realisation that money is mostly not real, the #metoo movement shocked many into the realisation that sexual harassment, abuse and rape is everywhere, the snail under the leaf.

Running with Claus Elholm’s theory that a big truth moment such as a financial crisis influences narration in literary fiction, it would seem the #metoo movement has been equally influential. Readers are craving truth, or the semblance of it, in our fiction. Unreliable narration feels tiresome when we’ve been lied to so deeply in our real lives.

I would expect that as more readers feel the impact of the climate disaster for themselves, the big lie that “Everything Is Fine, Business As Usual” will get the autofiction treatment in novels as well.

WHAT IS AUTOFICTIONALISATION?

A mode of narration that characterises many of these autofictional novels.

Claus Elholm Andersen at the High Theory Podcast

Mode of narration refers to how these novels are being told. The narrative consciousness or voice is placed with the experiencing character, not with the narrator.

WHAT IS IT FOR?

Certain modes of narration match better with certain themes.

Autofictionalisation suits stories which delve into themes around truth.

Autofiction lets authors describe their lives “in concrete particularity”. Using this technique, authors are able to “situate themselves in the potential and possible past by placing the narrative consciousness in that past.”

You may be wondering how autofiction is different from free indirect discourse in autobiography. Well, it is very much like that, except autofiction “allows for more precision about what is going on”.

EXAMPLES FROM LITERATURE

Claus Andersen offers the following two passages for a compare and contrast:

For a long time I used to go to bed early.

Marcel Proust, Swann’s Way (1913)

In the opening sentence to Swann’s Way, already we see a narrator in the present, looking back at his childhood. The narrative voice of consciousness is with the narrator, not with the little boy lying in a bed. (We could have picked any number of novels to demonstrate this very common mode of narration.)

Now for an example from My Struggle, ur-Autofiction of the modern world.

Knausgaard is eight-years-old, outside doing yard work. Just before he turns a corner he stops running. He’s really excited, but has been told he’s not allowed to run in the yard. Then he talks to his father. Before the father leaves the son, the father reminds him, “No running.” (Eight-year-old?) Knausgaard says:

How did he know I had been running? […] How the hell did he know I’d been running? […] How could he have known?

Karl Ove Knausgaard, My Struggle

The (adult) narrator (writing this passage) knows exactly how the father knew because he enjoys the adult benefit of hindsight. However, he keeps the reason from the reader. Readers don’t learn the reason for no running in the yard until the character learns it himself.

This narrative technique lets the reader experience the limited knowledge of Knausgaard’s eight-year-old self.

This is autofictionalisation.

IS AUTOFICTION A TYPE OF FICTION OR Nah?

When talking about autofictionalisation, Claus Andersen doesn’t use ‘fiction’ in ‘autofiction’ as it stands in opposition to ‘reality’. Instead, he is using the word ‘fiction’ to describe work informed by “newer rhetorical approaches” to fictionality.

In short, just because an author uses autofictionalisation as a mode of narration to tell their autobiography doesn’t mean they’re being untruthful about their own lives.

THE CASE FOR ABOLISHING THE TERM ALTOGETHER

The term auto-fiction is either an oxymoron or a tautology. Either way it’s redundant – a discussion.

Although the material may be factual based on one’s life, based on one’s autobiographical detail, the mere shaping of it into an artistic text makes it fictional. […] A writer can only write from within themselves. They can’t write from stuff that’s completely outside of themselves, stuff they’ve never experienced.

Marc Nash

NARRATIVE CLOSENESS IS A SPECTRUM

VERY-CLOSE THIRD PERSON: THE CASE OF SALLY ROONEY

Does the work of Irish novelist Sally Rooney count as autofiction?

The following is from a conversation between Sally Rooney and Kishani Widyaratna. Look for the episode called Normal People (May 2019) of the LRB Bookshop podcast. They talk about Rooney’s novel and where it sits in comparison to other literary fiction.

Sally Rooney confirms she likes the work of Sheila Heti and Ben Lerner very much. Rooney credits these authors with “changing the technology of the novel.” She’s a huge fan of Rachel Cusk.

Rooney explains how she’s interested in inhabiting the mundane, observing mundanity from within rather than stepping outside and observing it from there. So far, sounds a bit like autofiction, right?

Let’s think about the themes of Normal People. Are the themes typical of autofiction? Autofiction tends to explore truth, and what it means for something to be truth. At first glance, no. Kishani Widyaratna observes that the main characters in Normal People struggle with the question: “What is normal?” Falling in love, sexual desire, the transition from school to university. All of these are normal experiences, but so much of the characters’ internal monologue is them either trying to modulate their internal or external experiences. Rooney’s close psychological portraiture reminds Widyaratna of contemporary authors such as Sheila Heti and Ben Lerner.

Widyaratna points out the “quality of anxiety” which comes through in Rooney’s own mode of narration. The two main characters of Normal People are anxious types. This feels contemporary because we live in anxious times. To this description of her work, Rooney adds ‘precarity’ and ‘ambiguity within relationships’ as themes. Widyaratna describes Sally Rooney’s work as ‘hypersubjectivity’ and ‘incredible closeness’ (referring to the closeness of ‘close third person narration’). This mode, which Widyaratna describes as ‘realist’, reaches for a sense of truth or reality, “but from very different directions”.

On the topic of truth, Sally Rooney asks herself one question when writing: Does this scene work? She’s not thinking, while writing, about whether she’s trying to interrogate truth. If the scene is working she keeps writing. If it’s not, she does something different (takes someone out of the room, puts someone else in, invents a different conversation etc.). What does it mean ‘to work’? Does she mean ‘it rings true’? Does it ‘conform to a sense of reality or plausibility’? A scene is obviously much more than that, because it’s possible to write a very plausible scene which is still extremely boring to read. She goes on to say a scene has to be more than lifelike. It needs a kind of energy (which is also hard to define).

Sally Rooney points out that Heti and Lerner:

are writers who you might loosely say are writing in autofiction. That’s not a tradition that I’m directly engaged with here, but at the same time though, I don’t think there’s a whole lot of distance between me and my characters. Like, I don’t think that I’m standing behind my characters judging them, or trying to point out their foibles for the reader, or like, winking at them behind the character’s back as if to say oh, aren’t these people idiots, not like you and me. I think I’m sort of just there with them, and then often I am conflated with them in people’s responses to the book, which I completely understand. I think it’s because I have made that decision. There’s no ironic distance between me and the characters, or very rarely, and something I ever employ intentionally because it’s not what I’m trying to do. What I’m trying to do is just, sort of… observe them, and sort of be with them in a non-judgemental capacity, letting everything play out and then describing it sort of as neutrally as I can, and giving them all the tools that I have, making them just as capable of analysing their own emotional lives and their own interactions with others as I would be, which is sometimes a fair amount and sometimes not very much, but not trying to withhold anything from them.

Sally Rooney

It’s not lost on me that Sally Rooney’s very-close third person leads to people thinking she’s writing autobiography. Rooney also gets this when writing in first person:

One of the hazards of novels written in the first person is that people are quick to suggest that the book is biographical. Is this something you’ve encountered with Conversations with Friends?

The Irish Times

Oh my God, loads. Like loads. And people are so unabashed about it. When I was doing that Ryan Tubridy interview, it was breakfast radio, like 9am on RTÉ, and he’s like, “Have you ever had an affair with a married man?” I come on to talk about my book and I’m getting asked about my sex life. It’s so, so strange. So definitely on that level. But I made the mistake, in my opinion, of responding by saying “No”, when what I should’ve said was “It’s actually none of your business”.

This is a gendered phenomenon. Knausgaard avoids the charge by actually writing memoir, to the point where he’s upended his personal life by revealing private things about people he’s been close to.

Comically, woman writers field this assumption when writing speculative fiction:

MARGARET ATWOOD: I had a man in an audience once who during question period said to me, “Well, this story must be autobiographical.” And I said, “How could [The Handmaid’s Tale] be autobiographical? It’s set in the future.”

Margaret Atwood in conversation with Bill Moyers

Atwood also says this:

It’s a feature of our age that if you write a work of fiction, everyone assumes that the people and events in it are disguised biography. But if you write your biography, it’s equally assumed you’re lying your head off.

Margaret Atwood

Various authors are resisting the trend towards autofictionalisation:

I have no interest in sharing my own lived experience and I’m not into the testimonial turn literature has taken; I find the premise of immediacy suspicious. Literature is mediated – by language – and I’m more interested in doubling down on that mediation. I find the impossibility of us truly touching one another through language not only heart-rending but aesthetically more interesting than the [notion of] immediate connection. If ever I find myself on the page, I view it as an immense failure. For me, writing and erasing myself are one and the same; a sentence succeeds because it conjures up something other than me.

Hernan Diaz talking about his prize-winning novel Trust

I’ll leave you the cover of a book by Joanna Russ: How To Suppress Women’s Writing (a surprisingly funny read).

RETROSPECTIVE FIRST PERSON

Let’s go now to a completely different kind of first person narration: Retrospective first person.

Retrospective first is when a first person narrator tells a story about the past from a present moment. A example of this is Stephanie Vaughn’s “Dog Heaven,” which begins with the famous line, “Every so often, that dead dog dreams me up again.”

The narrator is telling a story that happened twenty-five years earlier. She lives in New York now, is an adult, but every now and then remembers the events of the story, when she was twelve and living on an Army base.

This POV is opposed to simple past, in which a narrator simply writes about what happened to them in some ambiguously close past moment, e.g. “I walked to the store, and my ex-wife was there. She did not look happy to see me.”

See the rest of Adam O’Fallon Price’s Twitter thread here.

O’Fallon Price contrasts this style of narration to the simple past, but I think autofiction is the far-inverse because there is no sense of past at all, even though the story clearly happened in the past (because here we are, being told all about it, and that’s how time works).

Poets like to contrast their perspectives as children with their perspectives as adults. Wordsworth did it in “Tintern Abbey,” and Frost did it in “Birches.” Dylan Thomas condenses the perspectives as he starts “Fern Hill” with the paradox of time then and now, “Now as I was.” Willie Nelson is nearly as clever and concise in a piece called “You Show Me Yours and I’ll Show You Mine.” The reference is to a childhood game, what we called “playing doctor”. Thus the child’s perspective. But the songs go on to fill in the blanks: “You show me your heart and I’ll show you mine,” and we are in the adult world. Wo with “You show me yours” we get the views of both child and man, just as we did in “Now as I was.”

Tammy Wynette and the Objective Correlative by George William Koon, 1983, Studies in Popular Culture

Advantages of retrospective first person

- This form of narration confers power to the ending. We are aware of how the story is building towards something, and we trust the something must be important.

- The narrator has had time to reflect on past events, which allows the story to contain more psychological complexity. Say the character was naïve in the past, they have experience now, looking back. This insight comes through in the story.

- The narrator can mess around with the timeline, telling bits from the deep past, skipping backwards and forwards from the time of writing. This allows the writer to position thematically and plot-related elements so that readers are most likely to draw the link.

- And in O’Fallon Price’s words: “The duration of time between telling and told is a mystery, a negative space in which the lightest brushstrokes feel vivid. Good writers can use this space to sketch out a life or portion of a life in a way that is often deeply satisfying.”

If those are the advantages of retrospective first person, we might expect those advantages disappear when writing autofiction.

WINKING FIRST PERSON?

In interview above, Sally Rooney talks about how she actively avoids winking to readers about her characters.

Is there such a thing as ‘winking first person narration’? Let’s coin it. The ‘Mark Twain Wink‘ is a thing, though Mark Twain wrote in third person. E.B. White was also a master of it. We see The Wink mostly in 20th century children’s books which have a clear dual audience. (A joke for the parent; a joke for the kid, or for the same kid when they read it again when older.)

Can you think of examples of first person narration which turns you into a conspirator with the writer? Hint: You may have to find books from an earlier age of literature. The very close third person mode of narration is popular now.

For me fiction is a way of asking: what if things were other than they are? And a central component of that is to ask: what if I was different than I am? I have always found the practice of writing fiction far more an escape from self than an exploration of it.

Zadie Smith, “The I Who Is Not Me”

All works of art are founded on a certain distance from the lived reality which is represented. […] It is the degree and manipulating of this distance, the conventions of distance, which constitute the style of the work. In the final analysis, “style” is art. And art is nothing more or less than various modes of stylized, dehumanized representation. […] But the notion of distance (and of dehumanization, as well) is misleading, unless one adds that the movement is not just away from but toward the world. The overcoming or transcending of the world in art is also a way of encountering the world, and of training or educating the will to be in the world.

Susan Sontag, “On Style”