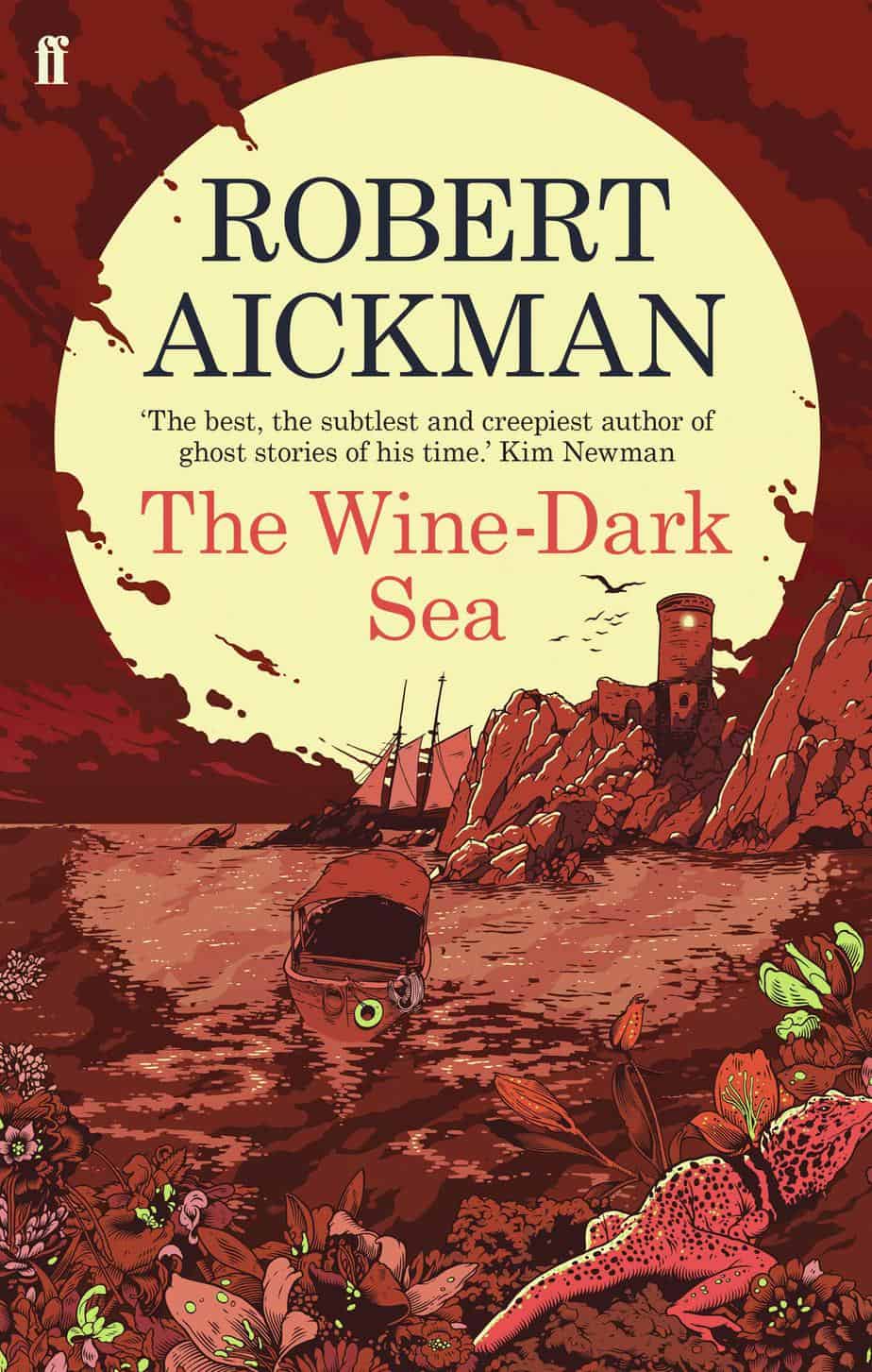

In the “Odyssey”, Homer famously describes the “wine-dark sea.” Well, that’s poetic, isn’t it?

But there’s a reason he didn’t just call the ocean blue. There was no term for ‘blue’ in Ancient Greece. People from antiquity didn’t consider blue a separate colour significant enough to name. It’s difficult to find a word that meant ‘blue’ way back in time. Black and white are mentioned a lot. Red, a little, next green and yellow. But no blue! Blue is one of the primary colours. In Japan there’s ‘midori’, which today means green (think of the liquor) but which is traditionally a sort of bluish-green colour, somewhere in the middle. Midori is traditionally ‘the colour of nature’, and describes the color of shoots, young leaves, or whole plants. There is a Japanese word for blue (ao). But educational materials distinguishing green and blue only came into use after World War II.

Now everyday Japanese has more specific words for blue than English does. In modern Japanese there are additional basic terms for light blue (mizuiro) and dark blue (ao) which are not found in English.

“We found that people who only speak Japanese distinguished more between light and dark blue than English speakers,” said Dr Athanasopoulos, whose research is published in the current edition of Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. “The degree to which Japanese-English bilinguals resembled either norm depended on which of their two languages they used more frequently.”

Bilinguals see the world in a different way, study suggests

Every language first had a word for black and for white, or dark and light. The next word for a colour to come into existence — in every language studied around the world — was red, the colour of blood and wine.

After red, historically, yellow appears, and later, green (though in a couple of languages, yellow and green switch places). The last of these colours to appear in every language is blue.

Kevin Loria for Business Insider

What else remains a significant conceptual gap in our culture, just waiting around to be named? And then, once it’s named, we won’t know how we rubbed along without it.

The Romans did not have a symbol for nothing (zero), and were so hampered by the lack that they were incapable of contributing to mathematical knowledge.

A.C. Grayling, The Reason Of Things

SKY AND THE HEAVENS

With our contemporary conceptions of colour, the sky can appear a vast array of different colours, but we mostly associate ‘sky’ with ‘blue’. Historically, we therefore associate this colour with the heavens.

Various other associations come from that main connection:

- truth and the intellect

- wisdom

- loyalty

- chastity

- peace

- piety

- contemplation

CHRISTIANITY

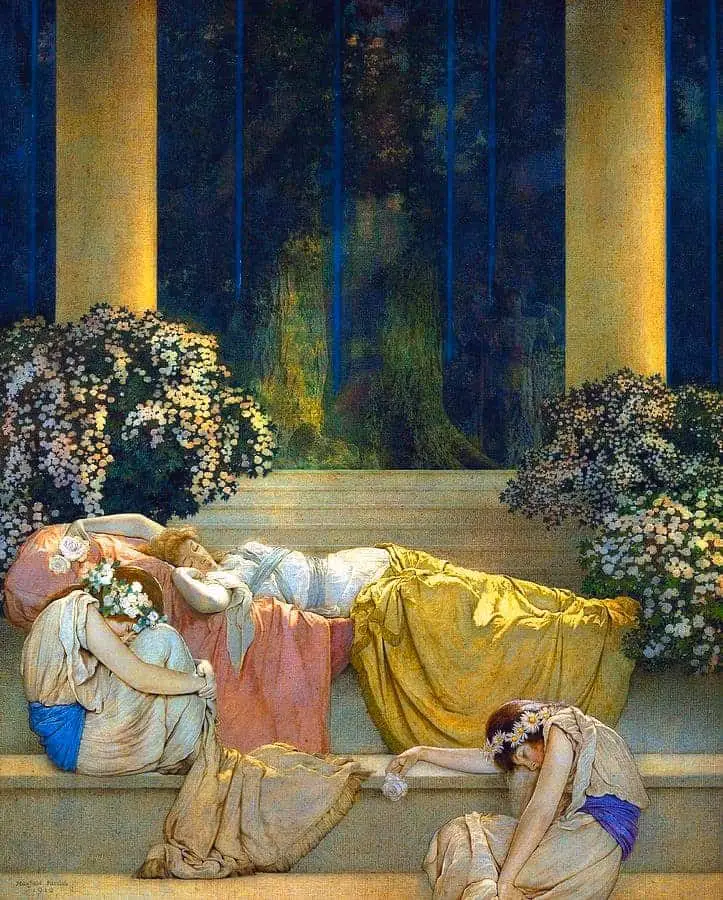

No surprise either, then, that blue is the colour worn by images of the Virgin Mary, who is supposed to embody all of the qualities in that list. If you see a young woman in a blue dress in a work of art, the work may be utilising the purity associations of the Virgin Mary.

AN EMOTION

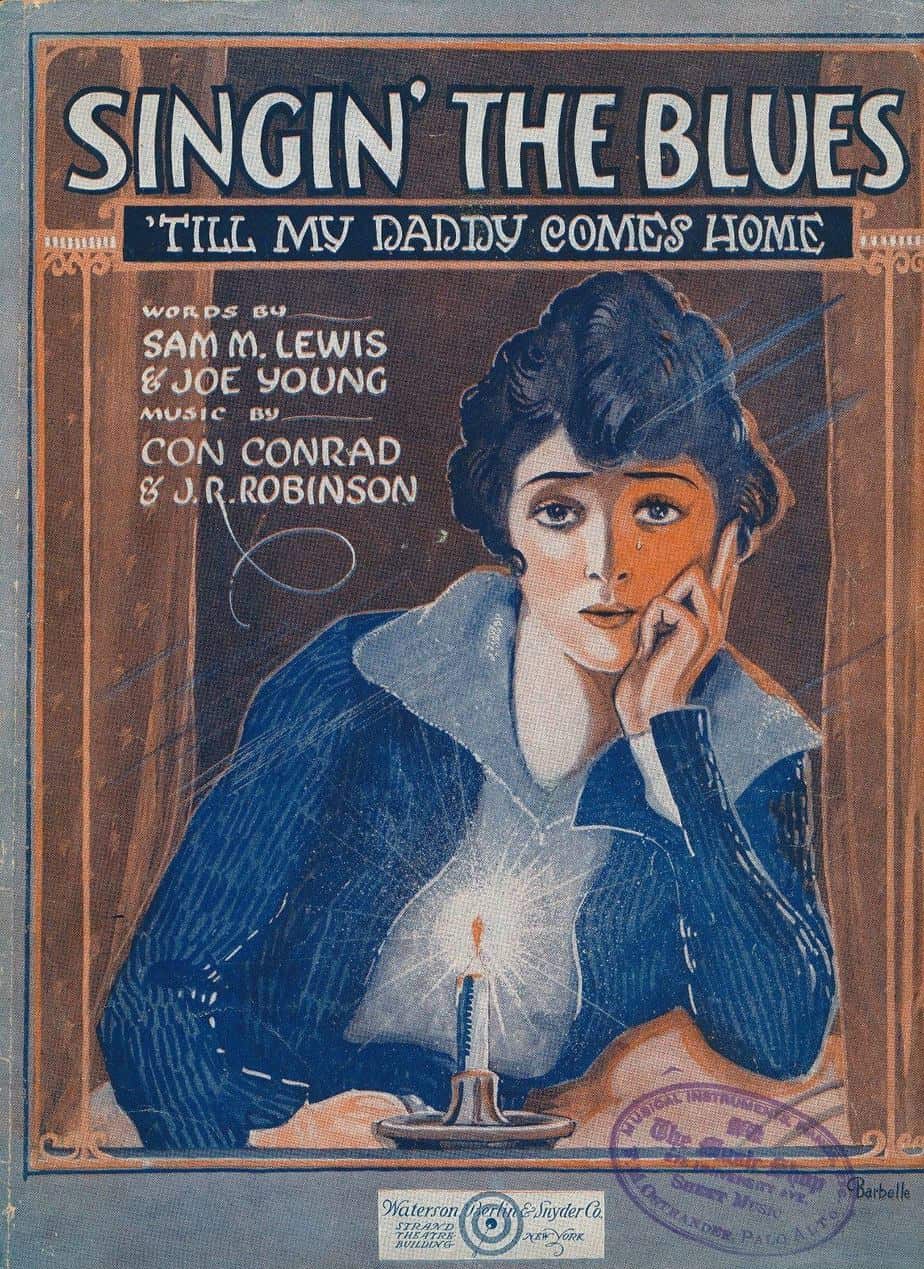

Blue is the symbolic inverse of the reds, oranges and yellows, which indicate carnival and fun. This cool colour has many variations but tends towards sober and sombre. Blue is also therefore associated with melancholy, loneliness, regret, saudade and related emotions.

MUSIC

Episode 52 of the Then Again Podcast: The Blues with Dr. Ben Wynne. “Historian, author, and professor Dr. Ben Wynne discusses the Blues in the American South with Glen during this virtual interview.”

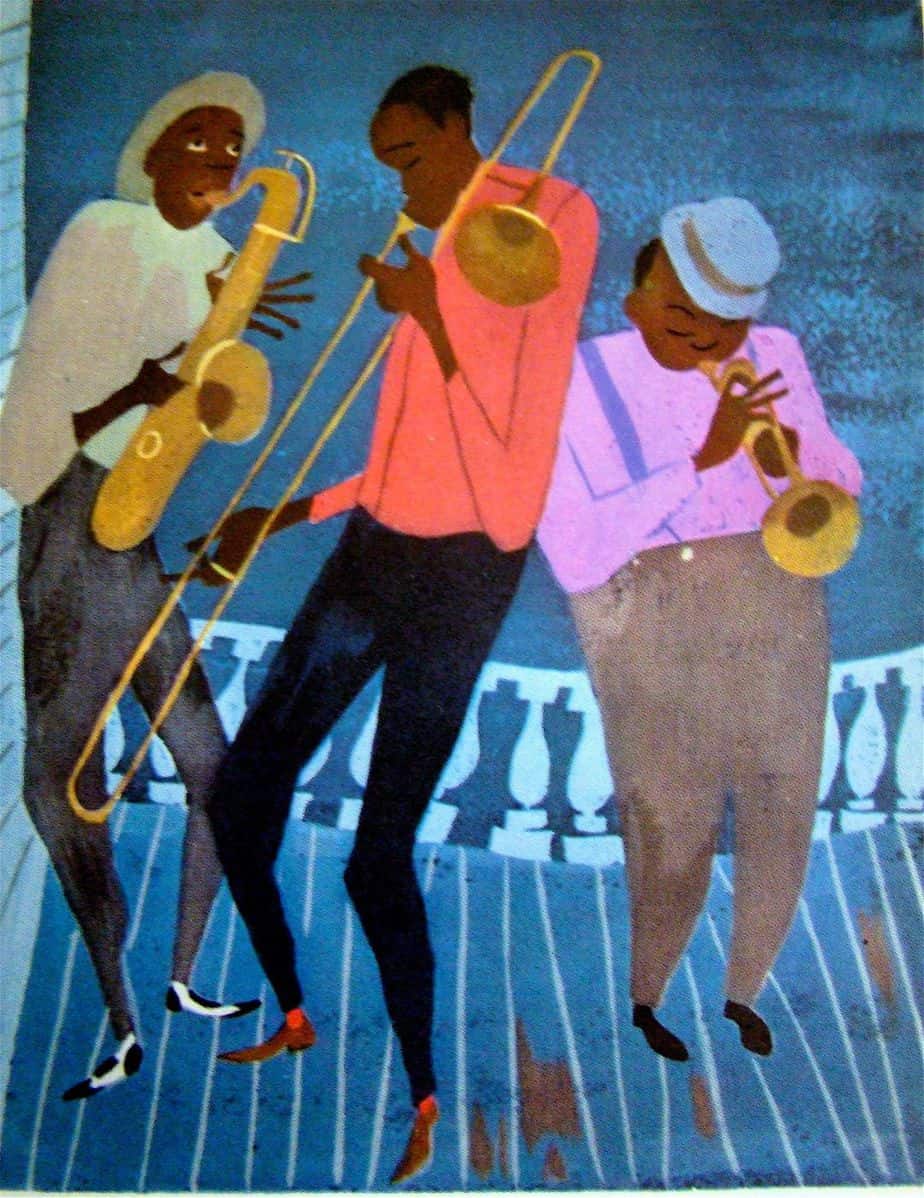

In music, ‘blue’ describes notes pitched a little lower to evoke those emotions. Billie Holiday’s Strange Fruit is a wonderful example of juxtaposition for devastating emotional effect: The colours described in the lyrics are bright and sunny. That helps the images of bodies hanging from trees to feel appropriately shocking. The images and the blue notes juxtapose against the romantic ‘pastoral scene of the gallant South’.

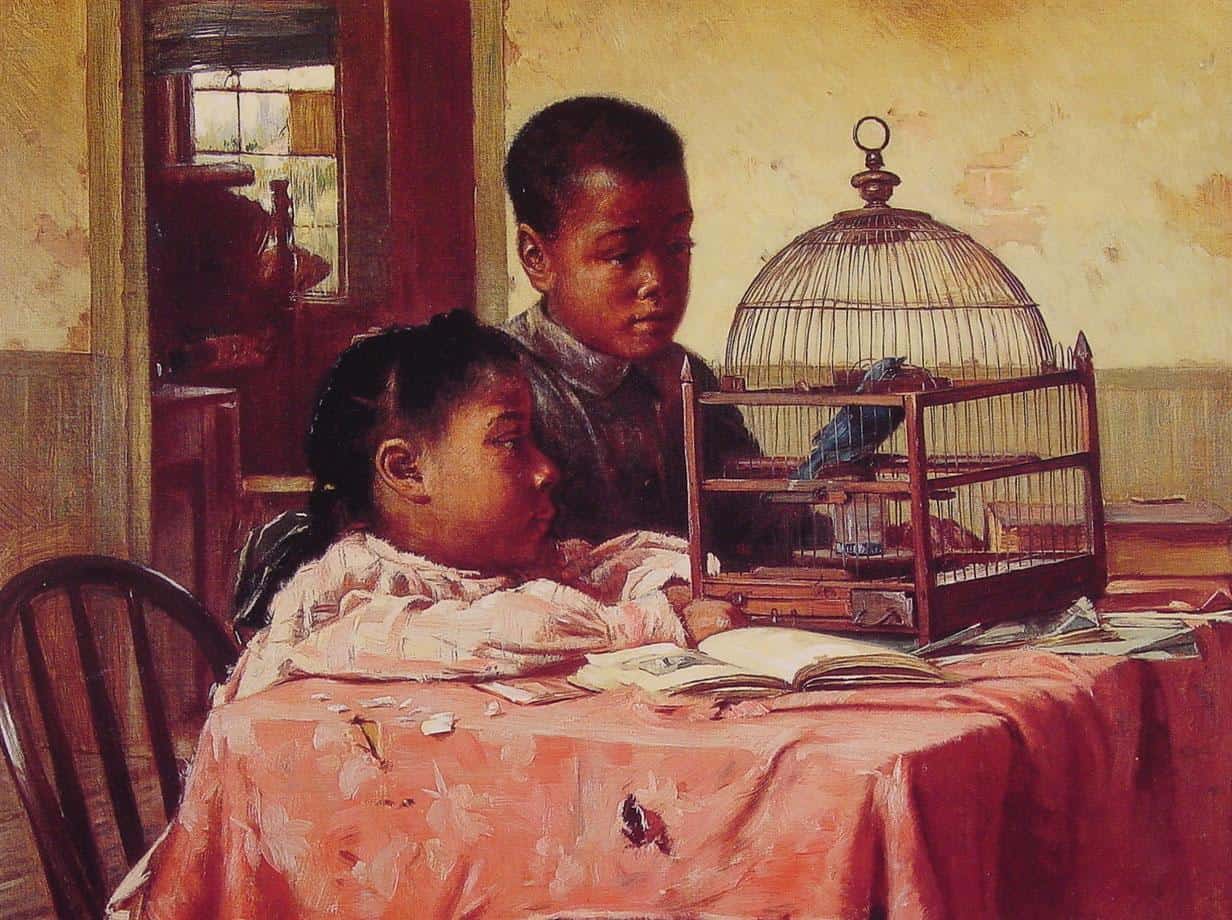

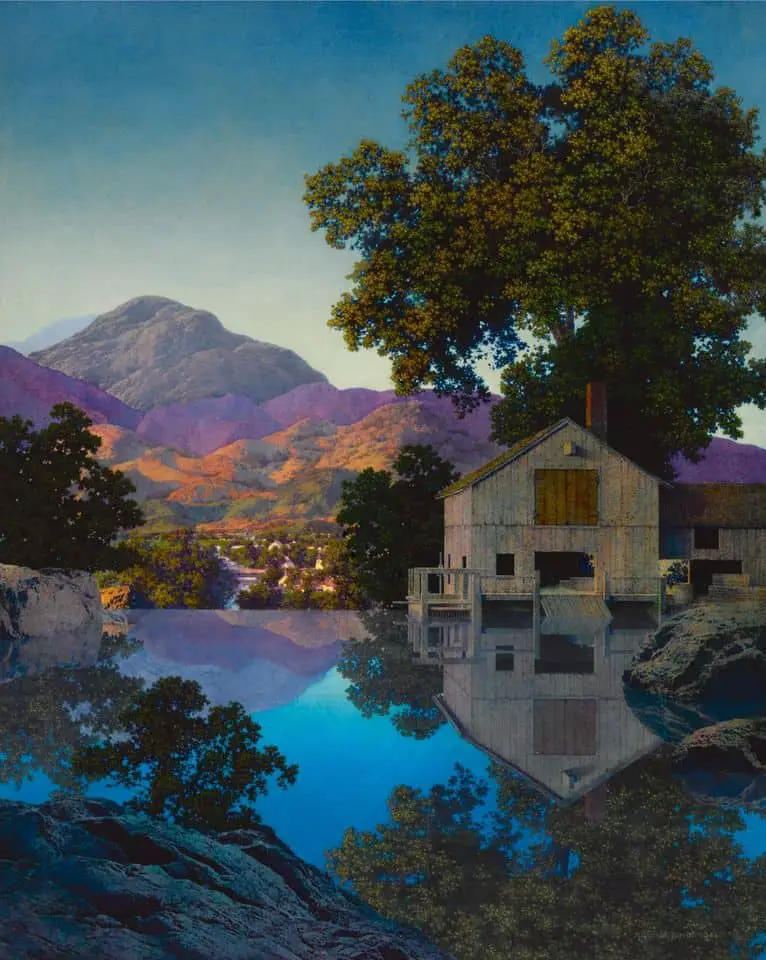

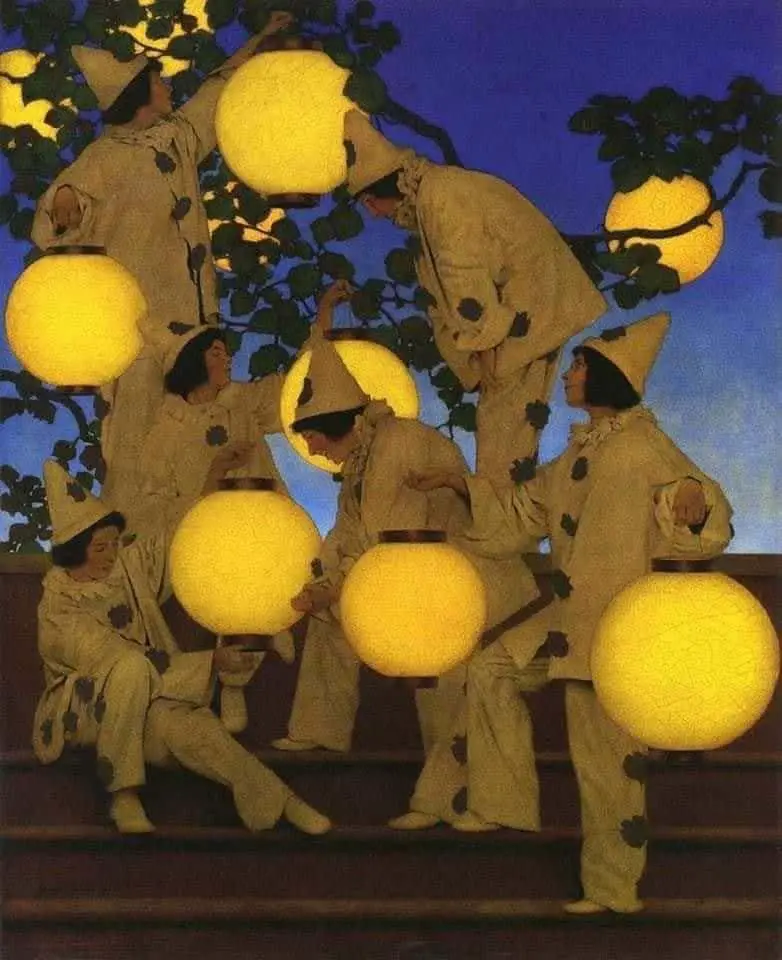

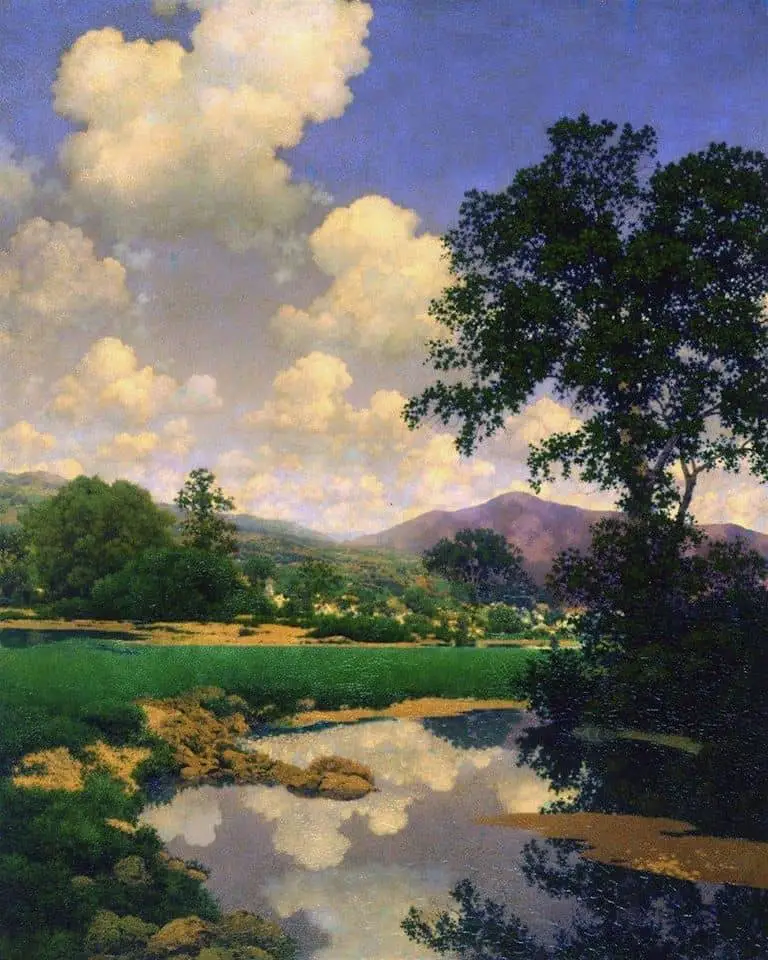

The painting below is an excellent example of blue used as juxtaposition against warm hues. In art this is known as making use of complementary colours. (Colour choice is scientific when it all boils down.)

HOPE

Though blue often indicates difficult emotions, it can indicate the inverse equally well. For instance, the bluebird is a widely recognised symbol for happiness. In the painting below, the patch of clear sky above indicates a break in the weather and is clearly a welcome sign against the murky, greenish hue of the churning water.

A clear sky generally means ‘infinite possibility’ and in this way, sky blue symbolises hope.

JUDAISM

In Jewish tradition Immortals lived in the city of Luz, also known as The Blue City. This is connected to the idea of this colour as endless, never-ending space.

HINDUISM

According to Hindu tradition, Mount Meru is a mythical sacred mountain. The southern face is supposed to be made of entirely of blue sapphires. This explained to Hindus why the sky is looks as it does — the sky is a reflection of the southern face of this mountain.

BLUE AS THE IMPOSSIBLE

Sometimes, when a thing is unexpectedly blue, this is a representation of the impossible. The blue rose is a good example.

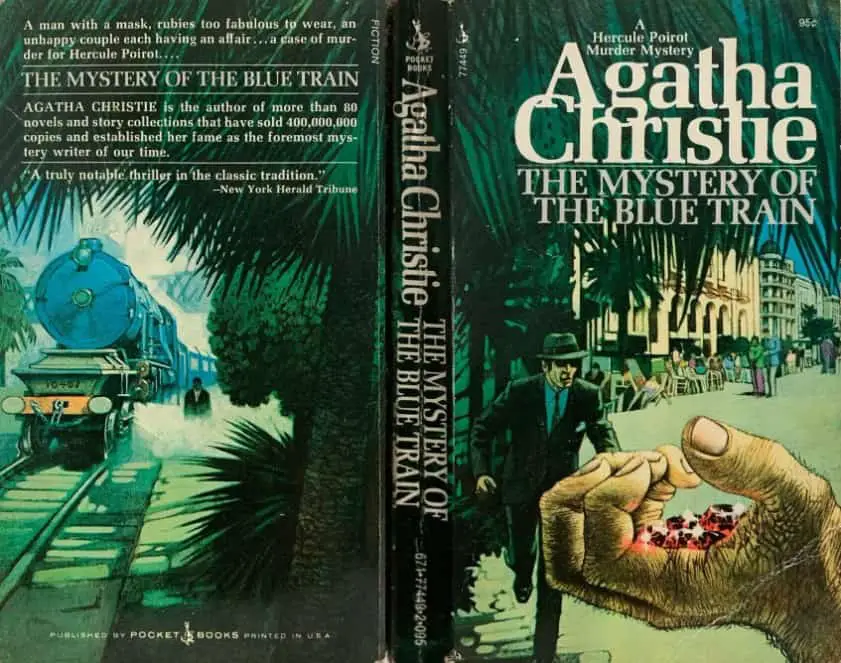

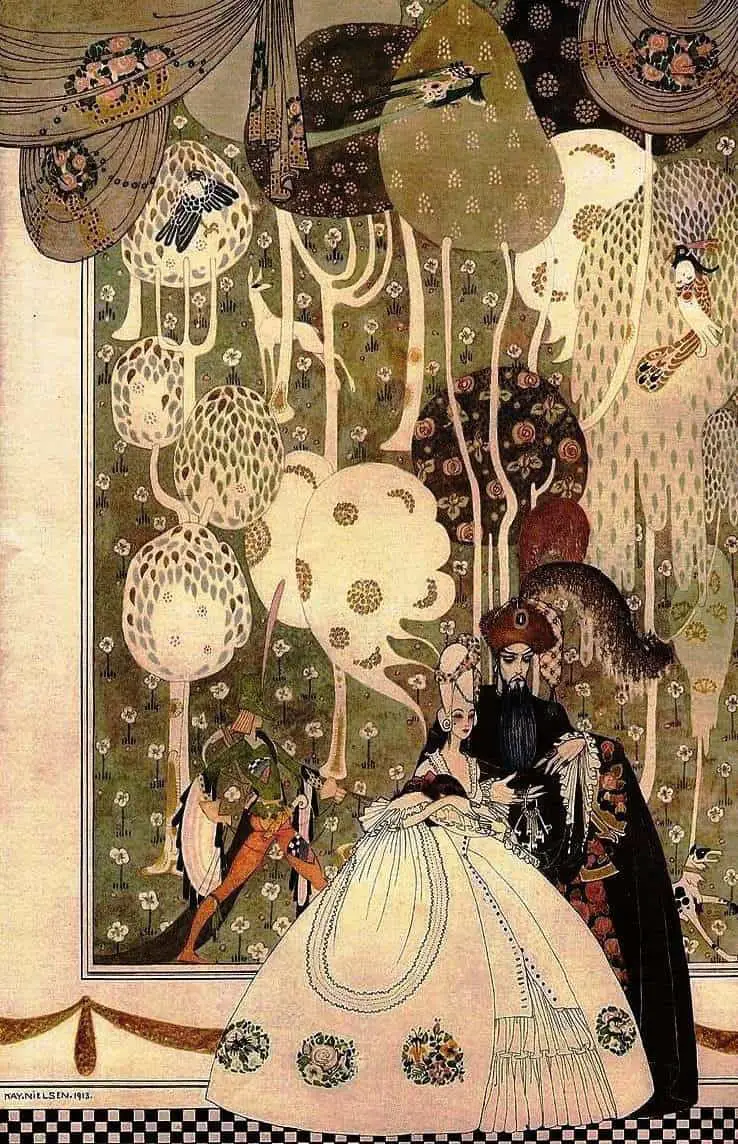

A fairytale like Bluebeard applies the colour to a human. This despicable human is considered an abomination — more monster than person. The blue tinge of his beard is a physical manifestation of his unnaturalness.

Green is used in a very similar way in other stories. Cf. green witches and green aliens, and the green skin of The Incredible Hulk.

THE BLUE HOUR

The blue hour (from French) is the period of twilight (in the morning or evening, around the nautical stage) when the Sun is at a significant depth below the horizon and residual, indirect sunlight takes on a predominantly blue shade, which differs from the one visible during most of a clear day, which is caused by Rayleigh scattering.

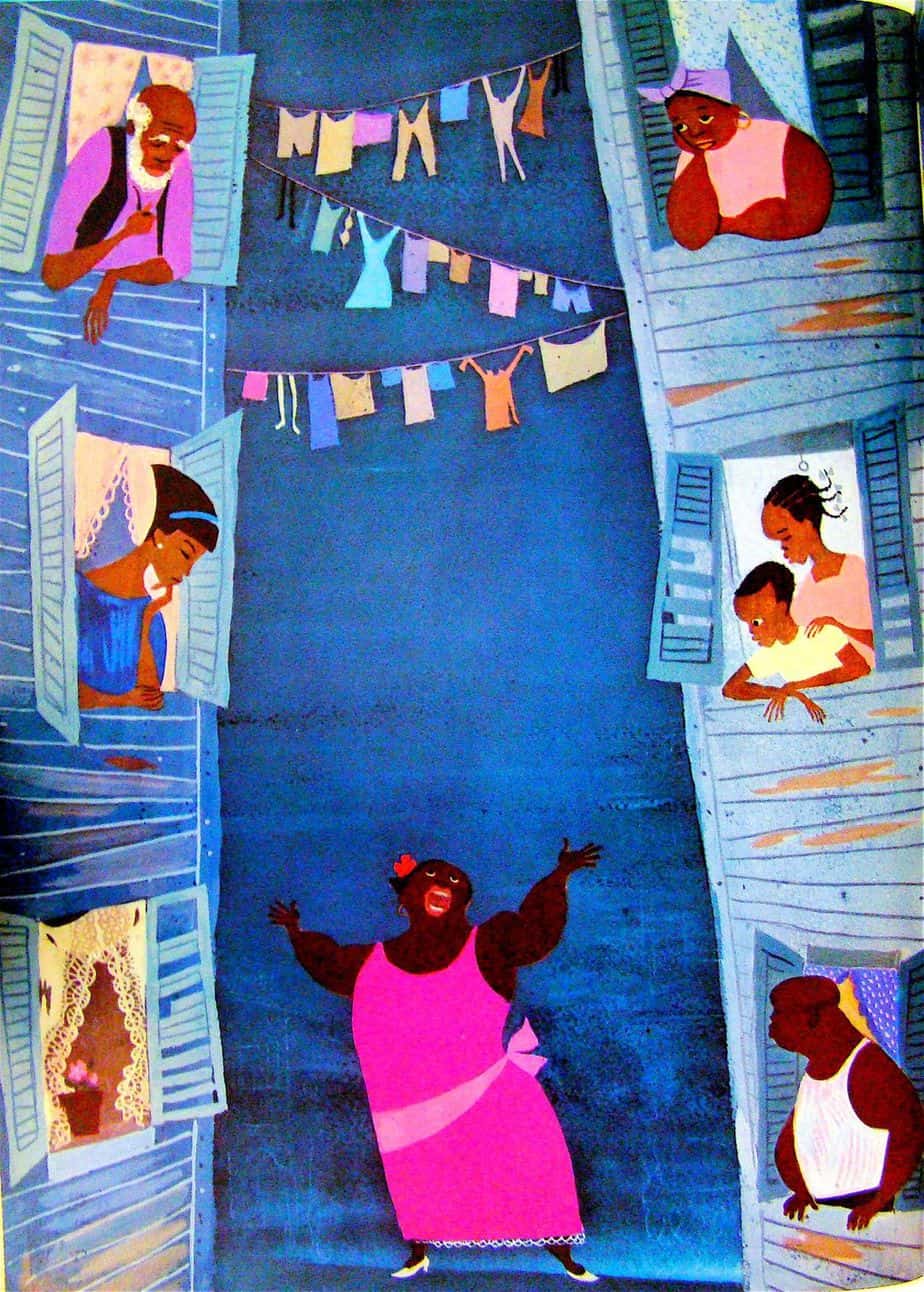

For the illustration below, Tom Lovell repurposes the concept and applies it to that time of day when Mother has had enough.

ULTRAMARINE

The Romans traded for lapis lazuli which was mined in Afghanistan as it still is today. They named the stone after its long journey from the east across the Mediterranean “Ultramarine blue” not because it looked like the blue of the sea but, because it came across the sea to Rome.

David Dunlop

(See painter David Dunlop’s post on ultramarine blue for the colour’s history in a nutshell.)

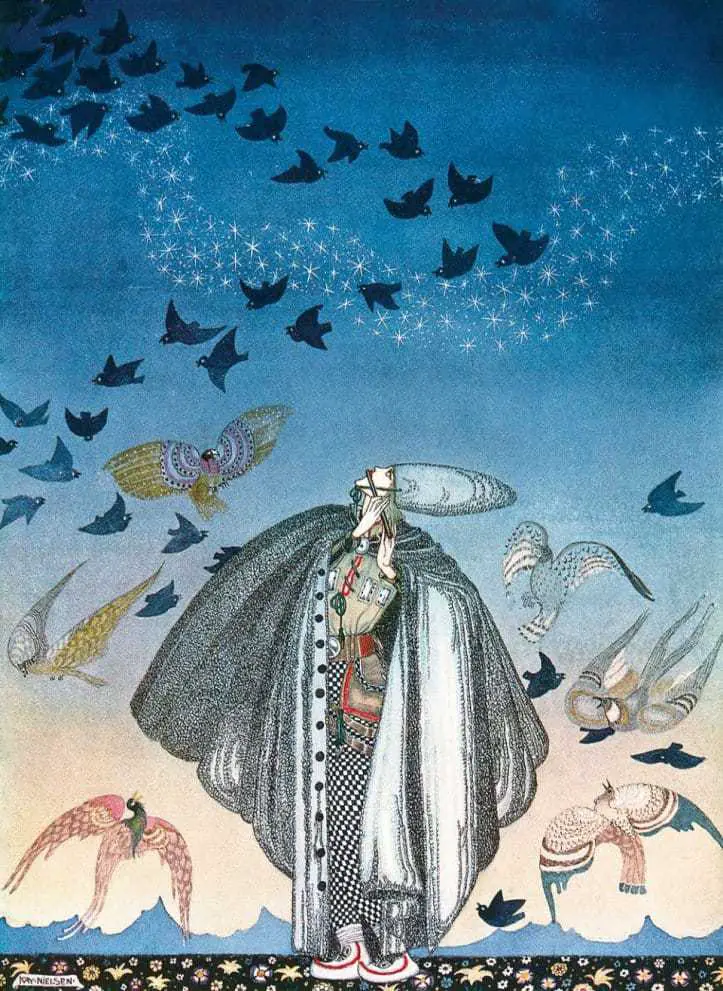

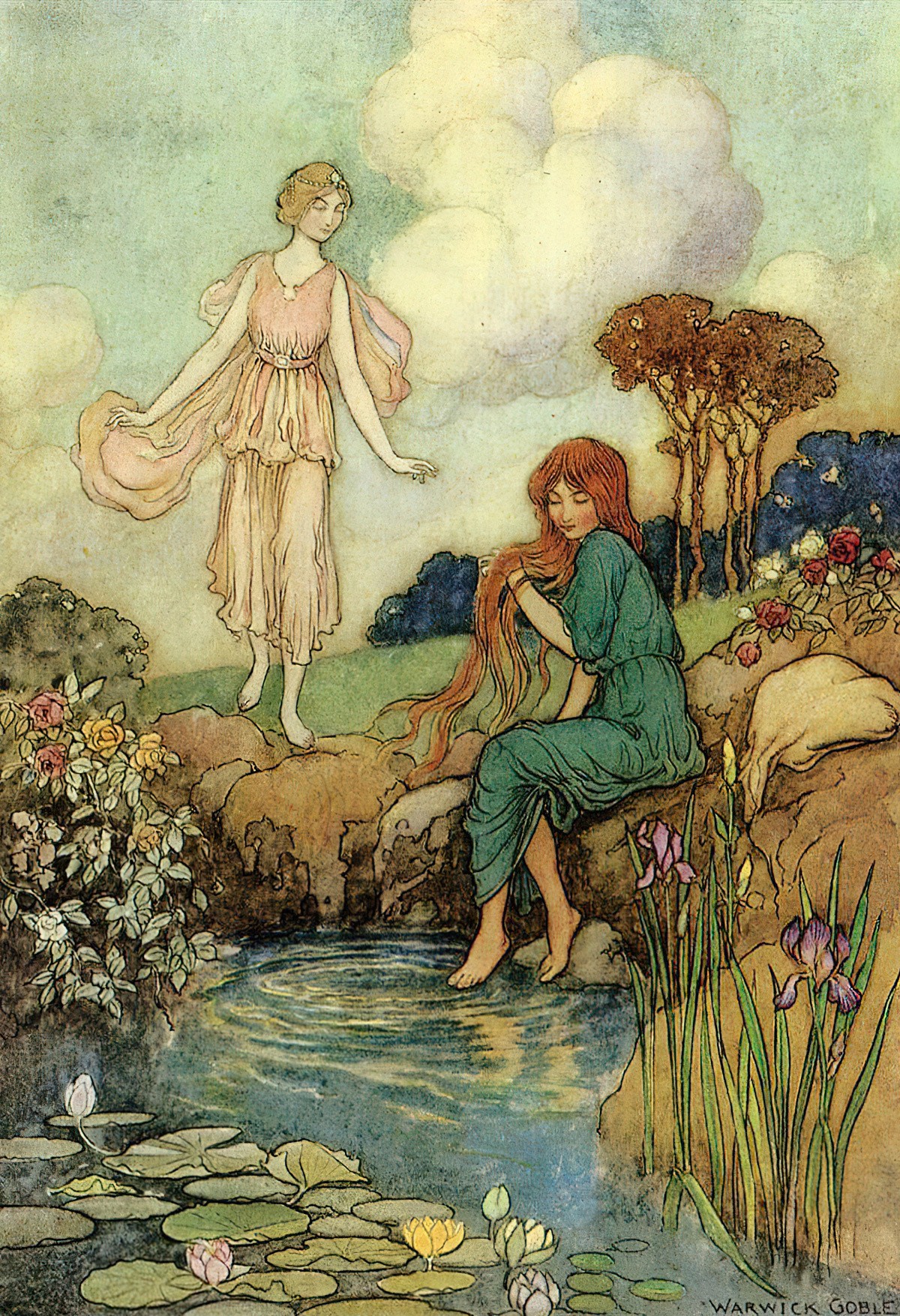

FLOWERS, BIRDS AND FAIRIES

Bluebells were a very common home for fairies around the time of the first world war? Why? [Perhaps the colour blue indicating virginity and purity had something to do with this choice of flower.]

STOCKINGS

The phrase ‘blue stocking’ comes from the late 17th century and, like the word ‘tomboy’ originally described a man rather than a woman. These men woreblue worsted (instead of formal black silk) stockings. This was extended to mean ‘in informal dress’.

Later the term denoted a person who attended the literary assemblies held ( c. 1750) by three London society ladies, where some of the men favoured less formal dress. The women who attended became known as blue-stocking ladies or blue-stockingers.

Then the phrase was used to insult intellectual young women who were more interested in ideas than in getting married.

It has since been reclaimed.

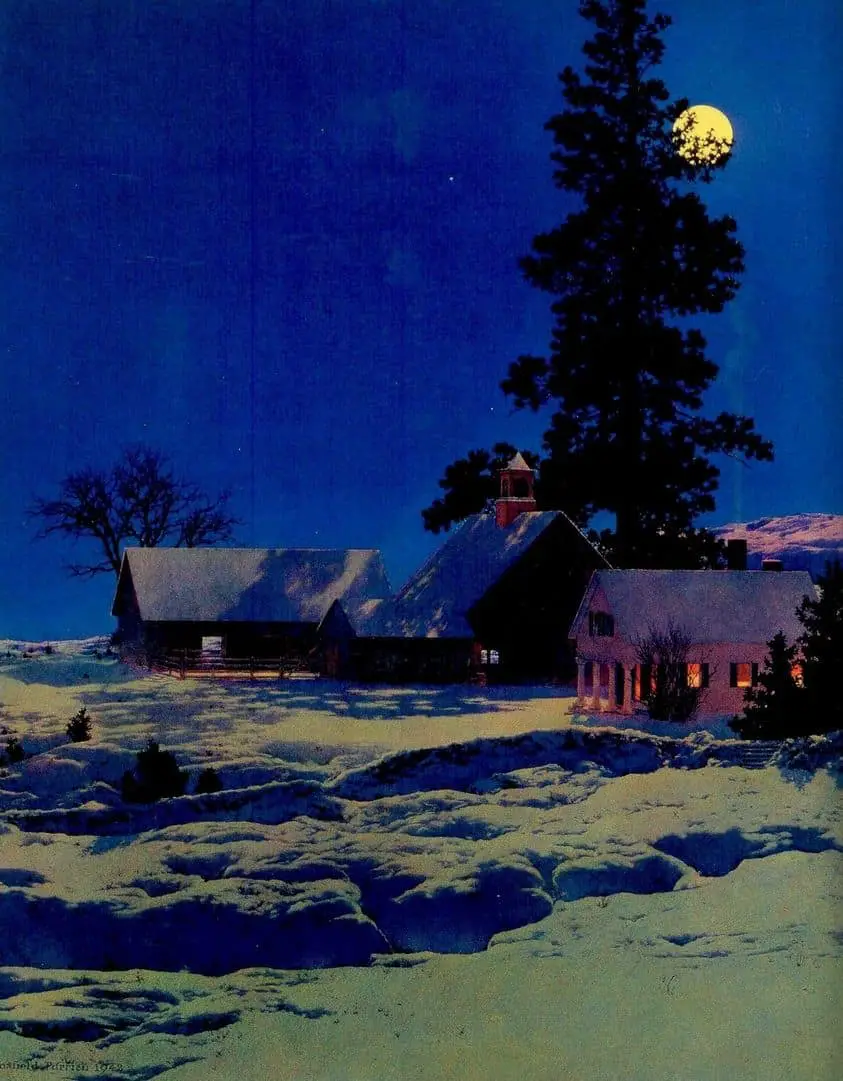

PARRISH BLUE

A blue used by Maxfield Parrish is so striking Parrish the artist has a colour named after him.

YVES KLEINIAN BLUE

Yves Klein is another artist who became known for his use of this colour.

The artist used blue as the vehicle for his quest to capture immateriality and the infinite. His celebrated bluer-than-blue hue, soon to be named ‘IKB’ (International Klein Blue), radiates colourful waves, engaging not only the eyes of the viewer, but in fact allowing us see with our souls, to read with our imaginations.

Biography of Yves Klein