Tally is about to turn sixteen, and she can’t wait. In just a few weeks she’ll have the operation that will turn her from a repellent ugly into a stunning pretty. And as a pretty, she’ll be catapulted into a high-tech paradise where her only job is to have fun.

But Tally’s new friend Shay isn’t sure she wants to become a pretty. When Shay runs away, Tally learns about a whole new side of the pretty world—and it isn’t very pretty. The authorities offer Tally a choice: find her friend and turn her in, or never turn pretty at all. Tally’s choice will change her world forever….

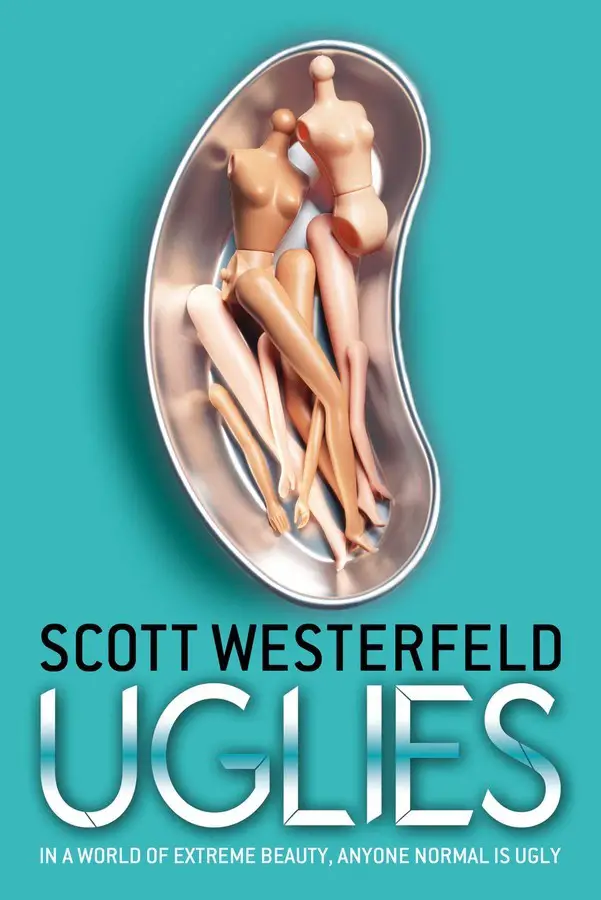

Marketing copy of Uglies by Scott Westerfield

Backstory

Flash forward

Painting the setting

Is it not good to make society full

Yang Yuan, quoted in The New York Times

of beautiful people?

NEW PRETTY TOWN

The early summer sky was the color of cat vomit.

The opening sentence makes use of stock yuck, more common in middle grade humour than in YAL. The danger is that some readers will be alienated. However, there is a thematic reason for the gross-out. This entire story is about the binary division between ‘ugly’ and ‘beautiful’. In a single sentence, an ‘early summer sky’ (typically considered beautiful) is rendered abject (disgusting).

Of course, Tally thought, you’d have to feed your cat only salmon-flavored cat food for a while, to get the pinks right. The scudding clouds did look a bit fishy, rippled into scales by a high-altitude wind. As the light faded, deep blue gaps of night peered through like an upside-down ocean, bottomless and cold.

The viewpoint character is named. Tally’s no writer, and has a quirky way of seeing the world (or at least, the sky). This world has cats in it. Also fish.

Any other summer, a sunset like this would have been beautiful. But nothing had been beautiful since Peris turned pretty. Losing your best friend sucks, even if it’s only for three months and two days.

A second main character is introduced. We don’t know yet if ‘three months and two days’ refers to what’s just been, or the timespan this story will cover. Nevertheless, it grounds us. For me, the name Peris is a little too close to penis.

Tally Youngblood was waiting for darkness.

This story can be said to have two separate openings. It’s now more clear that what we just read was a prologue (though it wasn’t named as such) and that this entire section is technically a flashback.

She could see New Pretty Town through her open window. The party towers were already lit up, and snakes of burning torches marked flickering pathways through the pleasure gardens. A few hot-air balloons pulled at their tethers against the darkening pink sky, their passengers shooting safety fireworks at other balloons and passing parasailers. Laughter and music skipped across the water like rocks thrown with just the right spin, their edges just as sharp against Tally’s nerves.

Is this a dystopian world? With the mention of ‘pleasure gardens’ and ‘safety fireworks’ this world feels like some evil person’s an attempt at utopia, but utopia has gone badly wrong. Snakes are a symbol of death. Burning torches take us back to Medieval, witch-burning times. This pink sky is not so much abject but scary (‘darkening’ — things are about to get worse). The author links the setting to character by comparing the sharp edged rocks to Tally’s nerves.

Around the outskirts of the city, cut off from town by the black oval of the river, everything was in darkness. Everyone ugly was in bed by now.

More blackness. Dark and black are repeating. ‘Everyone ugly was in bed now’ tells us there is one rule for beautiful people, another for the ugly. It sounds like ugly people are getting a raw deal.

Tally took off her interface ring and said, “Good night.”

Here we have unfamiliar technology, which tells us this is not like our own world. It is futuristic. We don’t know what an interface ring is…

“Sweet dreams, Tally,” said the room.

… but in a single sentence we have a pretty good idea. Funny how technology advances. The idea of an ‘interface ring’ hardly seems futuristic now.

She chewed up a toothbrush pill, punched her pillows, and shoved an old portable heater-one that produced about as much warmth as a sleeping, Tally-size human being-under the covers.

Right after the unfamiliar technology, the author grounds contemporary readers by listing items and actions that are familiar to us all. But with a twist. We know toothbrushes, we know pills. Toothbrush pills are novel. The final segment of this sentence confuses me until I read the next paragraph.

Then she crawled out the window.

Because here we learn that Tally went to great lengths to hide the fact of her absconding. We’re used to characters in stories shoving human-sized pillows under the covers; we’re not used to characters thinking about the amount of heat they give off. This probably connects the technology of the story world. Surveillance must be so tight that absence can be monitored via heat detection. By the way, characters moving beyond windows (and fences) is a common trope which kicks off adventure in children’s literature.

Outside, with the night finally turning coal black above her head, Tally instantly felt better. Maybe this was a stupid plan, but anything was better than another night awake in bed feeling sorry for herself. On the familiar leafy path down to the water’s edge, it was easy to imagine Peris stealing silently behind her, stifling laughter, ready for a night of spying on the new pretties. Together. She and Peris had figured out how to trick the house minder back when they were twelve, when the three-month difference in their ages seemed like it would never matter.

Another juxtaposition. The dark is normally scary, but for Tally it provides cover, and therefore comfort. Tally has a plan, but the audience doesn’t know what it is. By now we are interested to know what she’s up to and where she’s going. Like a heist plot, we’ll only find out as we see it play out on the page. With a snippet of backstory we learn these two characters grew up together. We have it confirmed that there are ‘house minders’ in this story. The part about the ‘three month difference’ suggests there’s an age at which people get ‘sorted’ into groups: Uglies and not Uglies, we suppose, guided by the paratext of the title, if nothing else.

“Best friends for life,” Tally muttered, fingering the tiny scar on her right palm. The water glistened through the trees, and she could hear the wavelets of a passing river skimmer’s wake slapping at the shore. She ducked, hiding in the reeds. Summer was always the best time for spying expeditions. The grass was high, it was never cold, and you didn’t have to stay awake through school the next day.

A scar is mentioned but not explained. It’s tempting in first drafts to mention and explain at the same time, but knowing when to hold back is key. This scar is Chekhov’s Gun; we’ll definitely hear more about it later.

We learn that even in this world, young characters have to go to school.

Of course, Peris could sleep as late as he wanted now. Just one of the advantages of being pretty.

We have it confirmed that pretty people get extra privileges. This is a caste system based on looks.

The old bridge stretched massively across the water, its huge iron frame as black as the sky. It had been built so long ago that it held up its own weight, without any support from hoverstruts. A million years from now, when the rest of the city had crumbled, the bridge would probably remain like a fossilized bone.

Authors sometimes go out of their way when creating futuristic, unusual storyworlds to give readers the impression that the world is an old one (and not just made up for the story at hand). The author does this with the age of the bridge. A (hypothetical) flash forward does the same in the opposite direction.

Unlike the other bridges into New Pretty Town, the old bridge couldn’t talk-or report trespassers, more importantly. But even silent, the bridge had always seemed very wise to Tally, as quietly knowing as some ancient tree.

The bridge is a tool of surveillance. Tally personifies it. By comparing the bridge to an ancient tree, the author continues to convey to the reader that this is an ancient story world. Also, the modern symbolic equivalent of an old tree is a human-made construction. This is a setting which humans have wrangled: No longer wise, just smart.

Her eyes were fully adjusted to the darkness now, and it took only seconds to find the fishing line tied to its usual rock. She yanked it, and heard the splash of the rope tumbling from where it had been hidden among the bridge supports. She kept pulling until the invisible fishing line turned into wet, knotted cord. The other end was still tied to the iron framework of the bridge. Tally pulled the rope taut and lashed it to the usual tree.

The next two paragraphs contain no backstory and only brief mentions of description. Readers are ready to hear what Tally is up to. Fish was mentioned in the opening few paragraphs. Now we see that fishing is a part of Tally’s life. She’s doing something with fishing line. The fisher-people of any village are generally living hand-to-mouth, making small but honest livings.

She had to duck into the grass once more as another river skimmer passed. The people dancing on its deck didn’t spot the rope stretched from bridge to shore. They never did. New pretties were always having too much fun to notice little things out of place.

We don’t know what a ‘river skimmer’ is but the following sentence tells us it has a ‘deck’, so we deduce it’s a very fast boat. In contrast, Tally has been talking about skimming stones. Again, nature versus technology.

When the skimmer’s lights had faded, Tally tested the rope with her whole weight. One time it had pulled loose from the tree, and both she and Peris had swung downward, then up and out over the middle of the river before falling off, tumbling into the cold water. She smiled at the memory, realizing she would rather be on that expedition, soaking wet in the cold with Peris—than dry and warm tonight, but alone.

Until now it’s possible she might be out fishing. But now we learn ‘she would rather be on that expedition’. This one is surely more dangerous. The flashback tells us what could happen, because it has happened before. Why would an author not have that happen to Tally now? Kind of exciting, right? Well, a summary is quicker, and this is the opening to a novel. Readers need to know what Tally is doing. This is not the time for a more lengthy, dramatised scene. A quick flashback works beautifully.

Hanging upside down, hands and knees clutching the knots along the rope, Tally pulled herself up into the dark framework of the bridge, then stole through its iron skeleton and across to New Pretty Town.

Tally is the acrobatic type, which is impressive. Her planning and daring are also impressive. This is a character we can respect. We now learn where she is going. I’m primed to learn what’s in New Pretty Town, and what happens when a non-pretty person dares go there.