Medical rooms and hospitals are safe, infantalising, dangerous, creepy, life-saving, traumatising places, and I offer them here as examples of what Foucault called ‘heterotopia‘.

The hospital’s ambiguous relationship to everyday social space has long been a central theme of hospital ethnography. Often, hospitals are presented either as isolated “islands’ defined by biomedical regulation of space (and time) or as continuations and reflections of everyday social space that are very much a part of the “mainland.’ This polarization of the debate overlooks hospitals’ paradoxical capacity to be simultaneously bounded and permeable, both sites of social control and spaces where alternative and transgressive social orders emerge and are contested. We suggest that Foucault’s concept of heterotopia usefully captures the complex relationships between order and disorder, stability and instability that define the hospital as a modernist institution of knowledge, governance, and improvement.

Heterotopia Studies

Hospitals (like airports) elicit the full range of human emotion and are symbolically useful arenas for storytellers. Who better than writers to describe what it feels like to be inside a hospital?

I followed [the psychiatrist] down a depressing hallway into a tiny windowless office that might have housed an accountant. In fact it reminded me a bit of Myron Axel’s closet, filled with piles of paper waiting to be filed, week-old cups of coffee turned into science experiments, and a litter of broken umbrellas nesting beneath the desk.

I must have looked as surprised as I felt when I entered her office, for Rowena Adler looked at the utilitarian clutter about her and said, “I’m sorry about this mess. I’m so used to it. I forget how it looks.”

Someday This Pain Will Be Useful To You by Peter Cameron

The author may have enjoyed writing that description because at James Sveck’s next appointment they are in a different room.

Dr Adler’s downtown office was a pleasanter place than her space at the Medical Center, but it wasn’t the sun-filled haven I had imagined. It was a rather small dark office in a suite of what I assumed were several small dark offices on the ground floor of an old apartment building on Tenth Street. In addition to her desk and chair there was a divan, another chair, a ficus tree, and some folkloric-looking weavings on the wall. And a bookcase of dreary books. I could tell they were all nonfiction because they all had titles divided by colons: Blah Blah Blah: The Blah Blah Blah of Blah Blah Blah. There was one window that probably faced an airshaft because the rattan shade was lowered in a way that suggested it was never raised. The walls were painted a pale yellow, in an obvious (but unsuccessful) attempt to “brighten up” the room.

The description of James’ psychiatrist’s rooms is broken up, judiciously, and fits around the action. James’ reaction to the rooms reflects how he feels about life at this juncture: He expected better. He expected different; instead he gets this underwhelming life.

I looked around her office. I know it sounds terrible, but I was discouraged by the ordinariness, the expectedness, of it. It was as if there was a catalog for therapists to order a complete office from: furniture, carpet, wall hangings, even the ficus tree seemed depressingly generic. Like one of those little paper pellets you put in water that puffs up and turns into a lotus blossom. This was like a puffed-up shrink’s office.

In a book of essays, Tim Kreider’s description of hospitals is one of the best I’ve encountered:

Hospitals are like the landscapes in recurring dreams: forgotten as though they’d never existed in the interims between visits, but instantly familiar once you return. As if they’ve been there all along, waiting for you while you’ve been away. The endlessly branching corridors sand circular nurses’ stations all look identical, like some infinite labyrinth in a Borges story. It takes a day or two to memorize the route from the lobby to your room. The innocuous landscape paintings that seem to have been specifically commissioned to leave no impression on the human brain are perversely seared into your long-term memory. You pass doorways through which you can occasionally see a bunch of Mylar balloons or a pair of pale, withered legs. Hospital beds are now just as science fiction predicted, with the patient’s vital signs digitally displayed overhead. Nurses no longer wear the white hose and red-cross caps of cartoons and pornography, but scrubs printed with patterns so relentlessly cheerful—hearts, teddy bears, suns and flowers and peace signs—they seem symptomatic of some Pollyannaish denial. The smell of hospitals is like small talk at a funeral—you know its function is to cover up something else. There’s a grim camaraderie in the hall and elevators. You don’t have to ask anybody how they’re doing. The fact that they’re there at all means the answer is: Could be better. I notice that no one who works in a hospital, whose responsibilities are matters of life and death, ever seems hurried or frantic, in contrast to all the freelance cartoonists and podcasters I know.

Time moves differently in hospitals—both slower and faster. The minutes stand still, but the hours evaporate. The day is long and structureless, measured only by the taking of vital signs, the changing of IV bags, medication schedules, occasional tests, mealtimes, trips to the bathroom, walks in the corridor. Once a day an actual doctor appears for about four minutes, and what she says during this time can either leave you and your family in terrified confusion or so reassured and grateful that you want to write her a thank-you note she’ll have framed. You cadge six-ounce cans of ginger ale from the nurses’ station. You no longer need to look at the menu in the diner across the street. You substitute meat loaf for bacon with your eggs. Why not? Breakfast and lunch are diurnal conventions that no longer apply to you. Sometimes you run errands back home for a cell phone or extra clothes. Eventually you look at your watch and realize visiting hours are almost over, and feel relieved, and then guilty.

Tim Kreider, “An Insult To The Brain”, We Learn Nothing

It’s a fact known throughout the universes that no matter how carefully the colours are chosen, institutional décor ends up either vomit green, unmentionable brown, nicotene yellow or surgical appliance pink.

Terry Pratchett, Equal Rites

They are now the only two people in the upstairs waiting room of the dental clinic. The seats are a pale mint-green colour. Marianne leafs through an issue of NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC and explores her mouth with the tip of her tongue. Connell looks at the magazine cover, a photograph of a monkey with huge eyes.

from “At The Clinic” by Sally Rooney

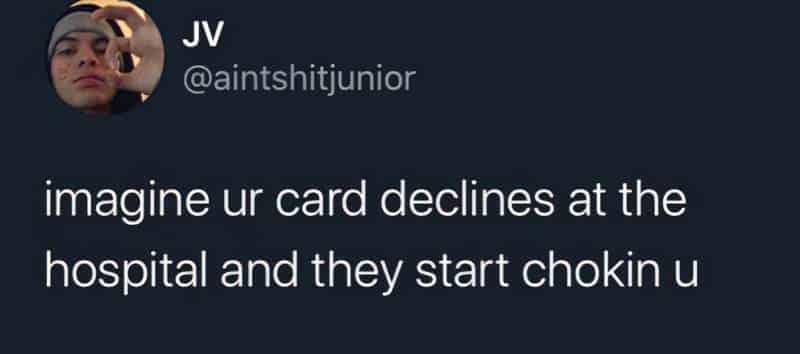

Every time I see a hospital in a horror movie or whatever, sometimes even an actual prison, I compare it to the one I went to and it always comes out looking worse. They are not relaxing places. They can leave you worse than you came in.

Especially because the world outside, doesn’t actually stop while you are there? You’re usually there due to a crisis. Something unexpected. Did you take vacation pay before you started? Probably not, hey? Provided that you get that sort of thing at all.

If you’re on welfare, you’re still have to fight for an exemption. Good luck if you can’t do that because you’re literally insane. You’ll still need to pay the rent and all your bills somehow in the background too. Oh, you got kicked out? That’s a shame.

Here’s a pamphlet to a homeless shelter. Have a lovely trip. My stay did turn out a lot better than that, but it’s literally only because I had someone constantly advocating for me on the outside. Most people in psych wards don’t get that.

And that’s not even touching on how nobody will listen to you in there, but everybody will assume all sorts of things about you. You’ll be open to both sexual and physical assault. Both happened to me on a number of occasions. I was blamed for everything, of course.

You don’t even get uninterrupted sleep, do you know that? Nurses come and shine a torch in your face every fucking hour for a wellness check, or whatever. Which feels pretty shitty if you’re going through a paranoid psychosis.

Anyway. I’d really like to see more empathy and awareness of the reality of all these sorts of places. They are horrible. They haven’t changed a lot since they were called asylums. They still use solitary confinement too, did you know that? Awful things.

Mx Maddison Stoff

@TheDescenters

FURTHER READING

What’s It Like To Work In A Psych Hospital? is a podcast from Psych Central with someone who explains how psychiatric hospitals are traumatising for everyone in and around them, not just for the patients.

The Architecture of Madness

Elaborately conceived, grandly constructed insane asylums—ranging in appearance from classical temples to Gothic castles—were once a common sight looming on the outskirts of American towns and cities. Many of these buildings were razed long ago, and those that remain stand as grim reminders of an often cruel system. For much of the nineteenth century, however, these asylums epitomized the widely held belief among doctors and social reformers that insanity was a curable disease and that environment—architecture in particular—was the most effective means of treatment.

In The Architecture of Madness: Insane Asylums in the United States (U Minnesota Press, 2007), Carla Yanni tells a compelling story of therapeutic design, from America’s earliest purpose—built institutions for the insane to the asylum construction frenzy in the second half of the century. At the center of Yanni’s inquiry is Dr. Thomas Kirkbride, a Pennsylvania-born Quaker, who in the 1840s devised a novel way to house the mentally diseased that emphasized segregation by severity of illness, ease of treatment and surveillance, and ventilation. After the Civil War, American architects designed Kirkbride-plan hospitals across the country.

Before the end of the century, interest in the Kirkbride plan had begun to decline. Many of the asylums had deteriorated into human warehouses, strengthening arguments against the monolithic structures advocated by Kirkbride. At the same time, the medical profession began embracing a more neurological approach to mental disease that considered architecture as largely irrelevant to its treatment.

Generously illustrated, The Architecture of Madness is a fresh and original look at the American medical establishment’s century-long preoccupation with therapeutic architecture as a way to cure social ills.

interview at New Books Network

The Architecture of Good Behavior: Psychology and Modern Institutional Design in Postwar America

Inspired by the rise of environmental psychology and increasing support for behavioral research after the Second World War, new initiatives at the federal, state, and local levels looked to influence the human psyche through form, or elicit desired behaviors with environmental incentives, implementing what Joy Knoblauch calls “psychological functionalism.”

Recruited by federal construction and research programs for institutional reform and expansion—which included hospitals, mental health centers, prisons, and public housing—architects theorized new ways to control behavior and make it more functional by exercising soft power, or power through persuasion, with their designs.

In the 1960s –1970s era of anti-institutional sentiment, they hoped to offer an enlightened, palatable, more humane solution to larger social problems related to health, mental health, justice, and security of the population by applying psychological expertise to institutional design.

In turn, Knoblauch argues, architects gained new roles as researchers, organizers, and writers while theories of confinement, territory, and surveillance proliferated. The Architecture of Good Behavior: Psychology and Modern Institutional Design in Postwar America (University of Pittsburgh Press) explores psychological functionalism as a political tool and the architectural projects funded by a postwar nation in its efforts to govern, exert control over, and ultimately pacify its patients, prisoners, and residents.

interview at New Books Network

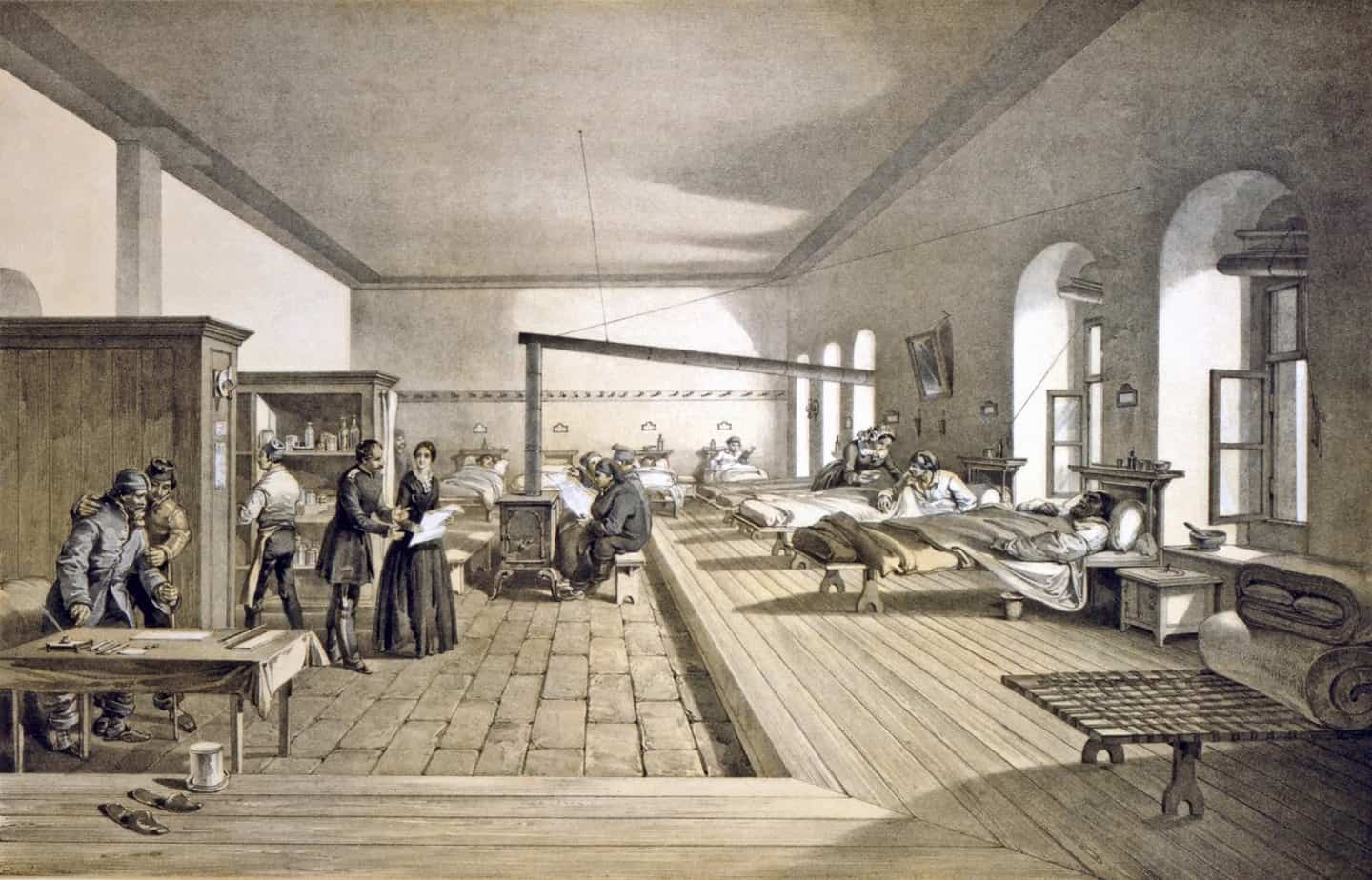

Header painting: William Simpson – One of the wards of the hospital at Scutari 1856