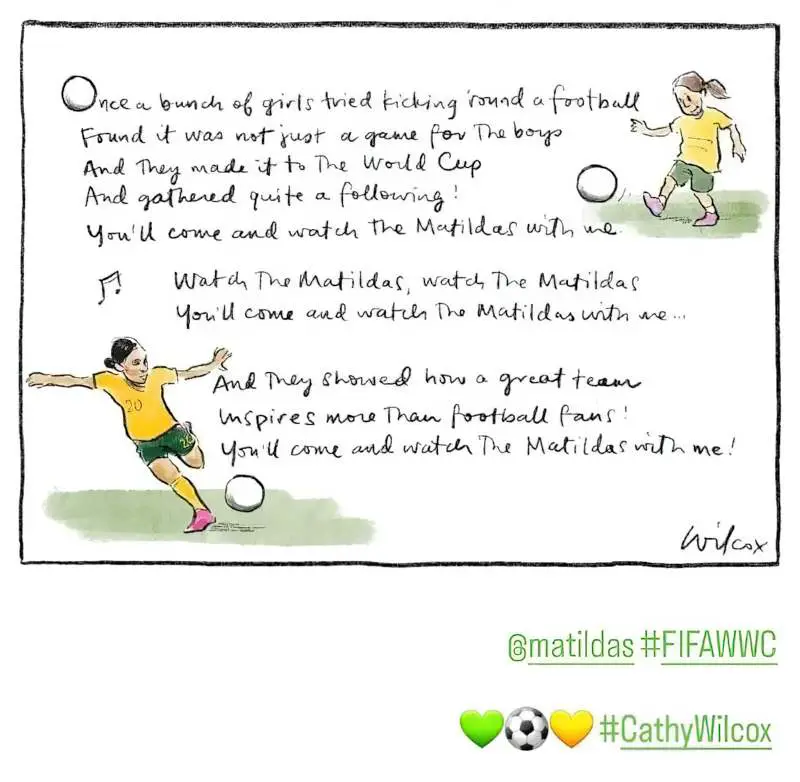

In 2023, the Australian women’s soccer team made the FIFA semi-finals for the first time, making history in numerous ways. For one thing, many soccer fans who had only ever followed men’s football were suddenly interested in watching the women. These guys weren’t watching ‘women’s soccer’. They were simply watching ‘soccer’. That’s a big win for Australian women’s sport — and for women in general.

Naturally, many people are wondering for the first time in 2023, why are The Matildas called The Matildas?

“Waltzing Matilda” is a famous Australian bush ballad by Banjo Paterson. (In Australia, ‘bush’ doesn’t mean ‘land covered in bushes’, but instead refers to vast swathes of land without much greenery in sight.)

I’ve written about “Waltzing Matilda” the bush ballad already, so lets focus on the “Matilda” of the song. As an Australian immigrant myself, I used to think Matilda was the swagman’s nickname for the sheep he stole before evading the law enforcement by throwing himself into the billabong to drown. But no. The Matilda does not refer to the sheep he tried to nick.

HOW A GERMAN WORD CAME TO REFER TO THE AUSTRALIAN WOMEN’S SOCCER TEAM

What I propose below is a possible etymological journey of the word “matilda”. Note that the word is contested. This is one possible route, and happens to be the etymology I personally consider most likely.

- In Old High German, “maht” meant “might and strength”. “Hild” meant “battle”.

- This gave rise to “Matilda” as a given name (also “Mathilda” and “Mathilde”. Because who doesn’t want their daughters to be strong in battle? Occasionally the name was given to boys, but whenever a name becomes slightly popular with girls, parents stop giving it to their sons. (A boy with a potentially ‘girl’ name is teased. In a gender hierarchy with men at the top, this doesn’t happen the other way around, which makes me think the ancient name was at first a boy’s name which later became feminised.)

- Variations on the name “Matilda” spread around the world, first introduced to the English-speaking world by the eleventh century Matilda of Flanders, queen of William the Conqueror, then used for his granddaughter, known as Maud.

- Like most names, “Matilda” as a baby name goes through cycles of popularity. Not surprisingly, given the FIFA Women’s World Cup was co-hosted by Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand this year, the name Matilda is having a moment. In Australia, Matilda is in the top ten most popular girl names for 2023. Overall, the name Matilda is most popular in the USA, but is also very popular in Australia and the UK.

- Australia is a large, harsh country thought historically unsuitable for Good Women (TM). However, there was historically another type of woman who men could contract to accompany him to the remotest parts of the country. These de facto wives were referred to collectively as “Matildas”.

- If a travelling man couldn’t afford or attract a real-life “Matilda”, he only had his bedroll and travelling possessions for company.

- There’s a linguistic phenomenon in which beloved objects are referred to as ‘she’. Ships are the best example. Men refer to their boats as ‘she’ and more frequently give them female names than male names. (This tradition is not worldwide. In Russia, ships are ‘he’.) Following this (heteronormative) tradition, men came to refer to their bundle of travelling gear as “Matildas”.

- For a time, “Matilda” was the commonly-understood Australian slang word for this bundle of possessions carried by a man in the Outback. It was probably most often some kind of sleeping gear wrapped around his cooking gear and perhaps a change of clothes. To “waltz Matilda” meant “to go bush while carrying a bundle of possessions”.

- Banjo Paterson cemented this historic phrase for posterity in his famous bush ballad, although it’s debatable how many contemporary Australians understand that the “matilda” refers to the bundle of possessions wrapped in bedroll (or a blanket or a bit of cloth, depending on how well-equipped he is). The contemporary Australian slang for portable bedroll is “swag” (cf. “swagman”). The modern swag purchased at outdoor supply stores is a luxurious thick mattress which comes inside a canvas tent with zippered flaps opening to fly-netting for fair-weathered nights. It costs about $500 and is best understood as a durable one-person tent.

- Some people argue that the term “matilda” comes from German immigrants, who commonly referred to their greatcoats as “Matilda”, supposedly because the coat kept them as warm as a woman would. In both cases, this is men in a context without women naming their items after women in the absence of women (and the sex and comfort women provide). It’s likely that German immigrants contributed in some way, because few things in life are either/or binaries.

- Now to how “Matilda” came to refer to the Australian women’s soccer team. When women’s soccer was first starting out, the national team had no name. Worse, people were starting to refer to them as “the female Socceroos” after the Australian men’s team. (Australians are pretty divided on how cringe they find “Socceroos” but that’s another story.)

- In 1995, the Australian Women’s Soccer Association teamed up with the national broadcasting service known as SBS and viewers were invited to suggest a proper name.

- The five finalists: Soccertoos, Blue Flyers (after the female Red Kangaroo), Waratahs (a native shrub with pink flowers), Lorikeets (a beautiful rainbow coloured parrot) and Matildas.

- These names were put to the public vote and “The Matildas” won. (Fortunately this preceded the era of Boaty McBoatface.) I do wonder if Lorikeets might be chosen today, given the strong modern connection between the queer community and the rainbow flag, and the understanding that women’s soccer has largely been created for and by the queer community.

- Although many today can see that “Soccertoos” would be worse by a long-shot, this particular form of misogyny (in which the ‘women’s version’ is contingent upon the men’s) wasn’t much noticed back in the mid 1990s outside feminist circles.

- Some of the 1995 players weren’t happy with “The Matildas”. They no doubt remembered what a Matilda referred to when Banjo Paterson wrote his famous bush ballad: The nickname given to women owned by men and considered disposable and unrespectable by society, including by the very men who literally used them as their mattresses to the point where the mattresses themselves came to be called after the women. Misogyny in a nutshell.

- Fast forward to the 2020s. I’ve noticed that when contemporary Australians hear “Matilda” they think of the bush ballad without thinking of the ‘women as bedding’ part. While Australians find it kind of funny that our unofficial national anthem is about a guy who tries to steal a sheep and then drowns himself in a murky pond, the vibe is fully inline with our convict ancestry feeding into larrikin culture. Most Australians who sing “Waltzing Matilda” today do not concern themselves with the etymology of the erstwhile misogynist slang-word “matilda”, and haven’t tracked the journey it took between “strong warrior” and “ho for the road”. (Sex work is work; until all women are respected, no women are.)

- Has “The Matildas” been reclaimed? Yes, I’d say so. Whenever the name of the Australian Women’s Soccer Team is queried, its defenders tend to refer back to the Old High German etymology. What’s wrong with ‘strong warrior?’ they ask.

- Also, “Waltzing Matilda” is such a catchy tune, it makes for a great sporting chant. Anyone can sing it, even if you can’t hold a tune. And people are starting to feel that “Aussie, Aussie, Aussie, oi, oi, oi!” is too cringe and are hunting for something new, especially since women’s sport is finally having a moment. Note that the Australian National Anthem has changed twice in recent history in an attempt at inclusion. “Australians all let us rejoice” was quite recently “Australia’s sons let us rejoice”. Even more recently, and less successfully in the view of many, “For we are young and free” was updated to “For we are one and free”. Australians are quite used to updating problematic folk ballads and we soon forget original lyrics and any erstwhile problematic connotations.

IS “THE MATILDAS” SOCCER NAME SEXIST?

The question is simplistic and I reject it.

Language evolves in tandem with its culture. As a consequence, patriarchal cultures (all of them) give rise to patriarchal language. There are many words we must reject if words with sexist origins taboo. We’d avoid words like ‘hysteria’, for starters, and every single word that has ever existed to describe ‘woman’, because any ordinary word which refers to women without fail eventually comes to mean ‘dirty sex worker’. That’s not the word’s fault; it’s the culture’s.

Are people who defend the name “The Matildas” sexist? Sexist people are sexist, and in a sexist culture everyone’s a little bit sexist, but most who defend the name “The Matildas” consider it reclaimed, or prefer to go back to the original meaning of Matilda as ‘strong in battle’.

Personally, I would prefer people understood the wider misogynistic history of the name because when we recognise misogyny so very clearly in a historical context, it then becomes easier to see it repeating in a modern context.

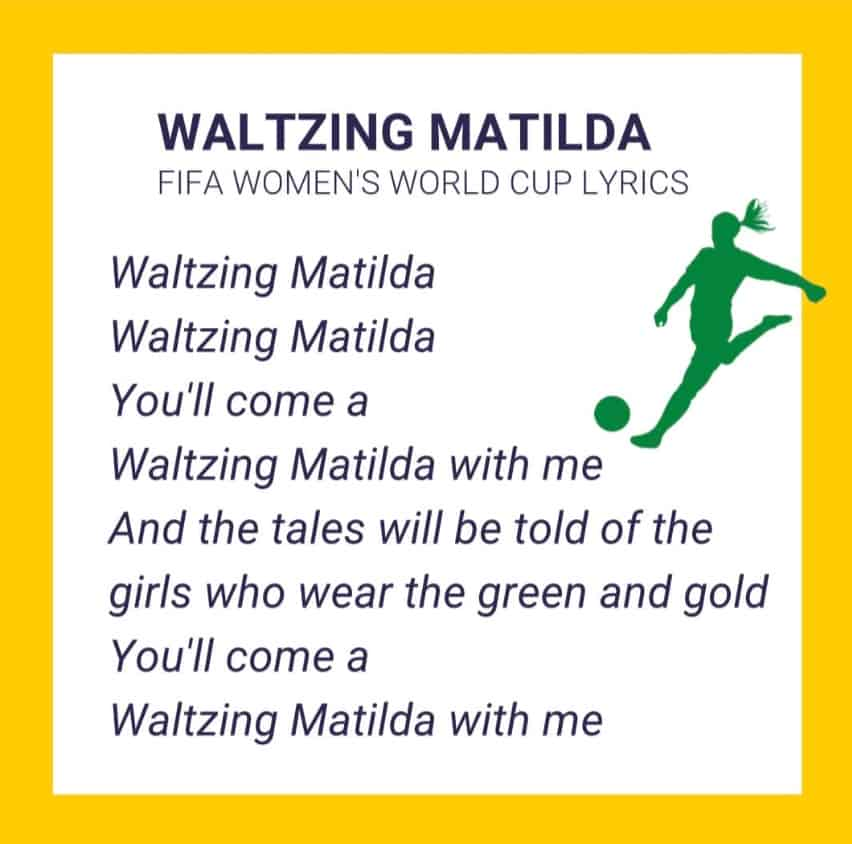

AUSTRALIAN SPORTING CHANTS BASED ON “WALTING MATILDA”

Whatever you think about “The Matildas”, let’s take a moment to consider the name of the English National Women’s Football team: