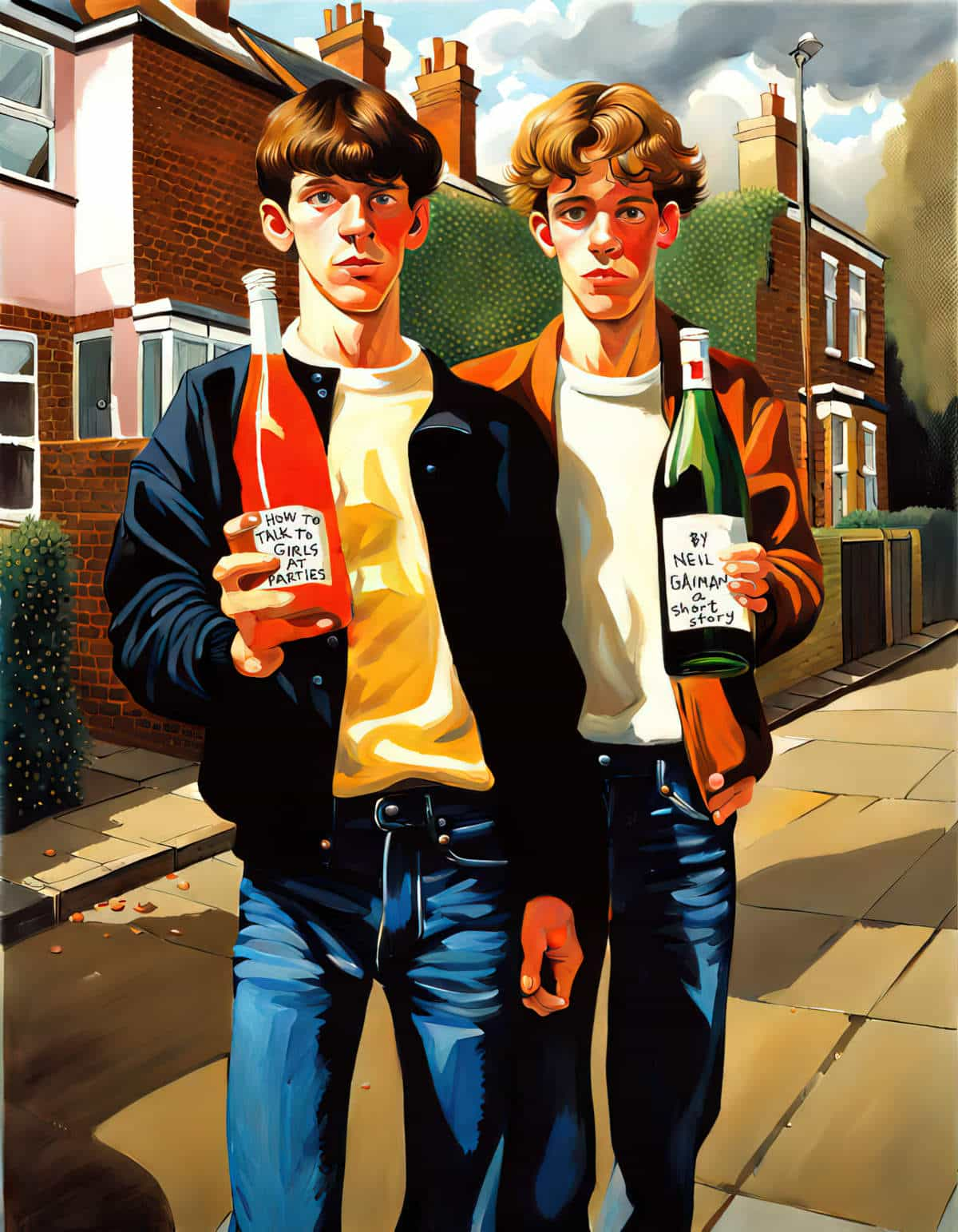

“How To Talk To Girls At Parties” is a 2006 short story by British author Neil Gaiman. The author has posted the text version of this story at his own website, which you can read for free. Alternatively, find it in his Smoke and Mirrors collection.

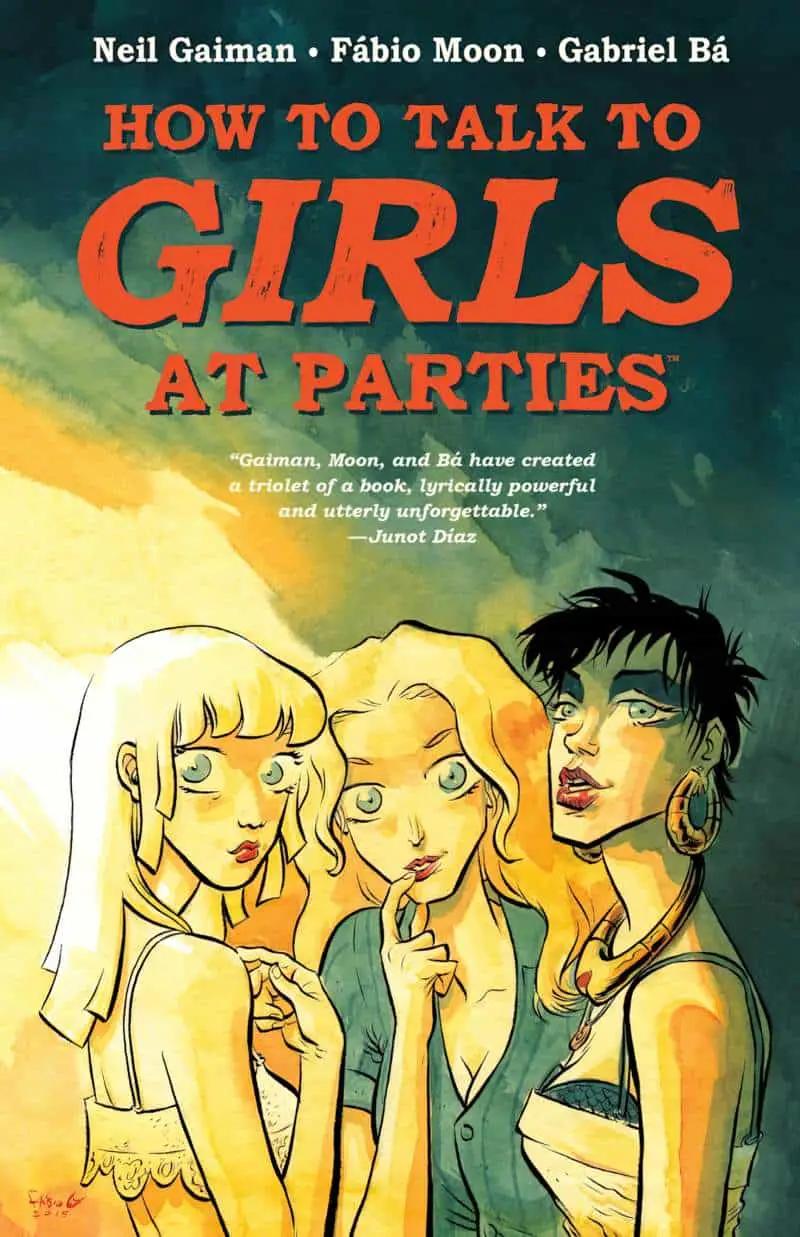

There is also an audio version (the link currently doesn’t work though) and you may be able to find the comic adaptation, beautifully illustrated by Brazilian twins Fábio Moon and Gabriel Bá. (Weirdly, these guys look like Neil Gaiman, which means all three creators of this comic look like Neil Gaiman.) The brothers have a Blogspot blog.

“How To Talk To Girls at Parties” is also a 2017 film starring the most ethereal looking actresses you can imagine. Tell me, who springs to mind? If you’re thinking of Elle Fanning and Nicole Kidman, you’re thinking along the same lines as the casting director. Elle’s sister Dakota starred as a young child in a 2002 sci-fi TV series called Taken, which I rarely hear anything about these days. Anyway, those sisters, with their big eyes and almost transparent complexions, are perfect for the role of ‘beautiful alien’.

However, the film scores 5.7 on IMDb, which is precisely what I thought it would get. My focus today is limited to Neil Gaiman’s original short story. This kind of short story, with that ending, is not the kind of short story which makes for a good feature film. John Cameron Mitchell spun it out to 1hr 42 minutes. If he’d made a 25 minute short film instead, then he’d capture my interest. (This is no Brokeback Mountain, a short story with so much novelistic potential it maps well onto feature film length.)

“HOW TO TALK TO GIRLS AT PARTIES” IN A NUTSHELL

Two 15-year-old boys called Enn and Vic attend a party. Enn didn’t want to go. At the party — which was not the party they were looking for — weird music plays. Weird conversations happen; the girls are ethereal and speak oddly. They walk home the same route — separately. The viewpoint character’s friend is all shook up by something he cannot possibly talk about with his friend.

To me, this is an allegory for sexual assault. We rarely talk about the sexual assault of young men. The very concept of ‘unwanted sex’ for teenage boys is apparently too much for many people to wrap their head around, so this story occupies an important gap in the narrative.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS FOR “HOW TO TALK TO GIRLS AT PARTIES”

- The narrator doesn’t want to attend the party because his mate is better-looking and more confident. Name some other stories which feature a reflective narrator who is trailing along with their more confident (but also more rash and careless) friend.

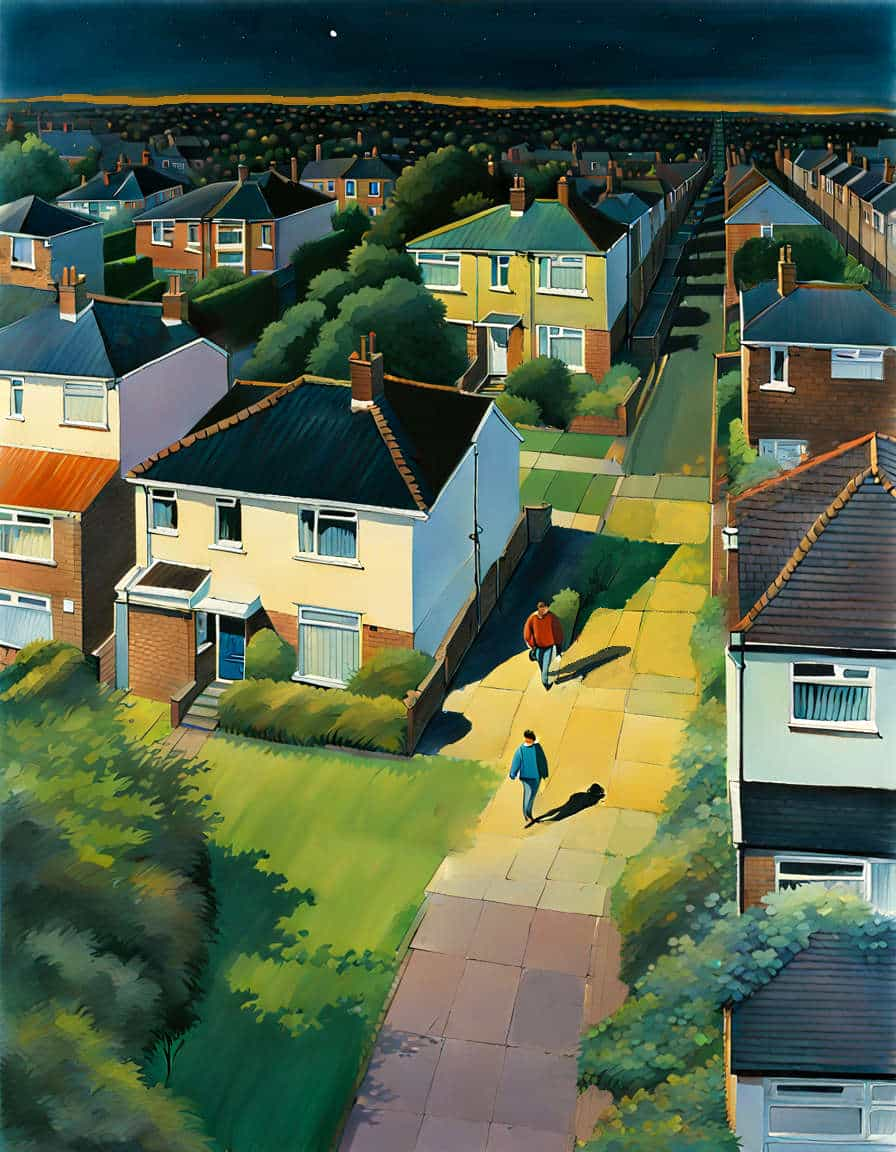

- The story is set in East Croydon, London. Describe this part of the world, or how it was in the late 1970s. What was going on in England at this time?

- In children’s stories, authors frequently lampshade parental absence, meaning the narrator tends to explain why the kids are allowed to be out and about by themselves, often at night. How does Neil Gaiman explain why the boys are enjoying some newfound freedom on this particular evening?

- There’s no fantasy portal in this story (not a mirror, not an elevator, not a cookie jar…) but as the boys walk towards the party house, the setting feels as if the characters are entering another world. How does Neil Gaiman convey that sense of Other place, even within the boys’ familiar environment of south London?

- The big irony of this story: Common wisdom has it that, given sufficient confidence, boys find it easy to talk to girls because girls aren’t aliens. Yet the girls in this story literally are aliens. Where else in the story does Neil Gaiman take common wisdom and deploy it to literal (science fiction) effect?

- Do you feel satisfied by the ending, or would you have preferred something else/more?

SETTING OF “HOW TO TALK TO GIRLS AT PARTIES”

- “How To Talk To Girls at Parties” is set in 1976 (the movie in 1977).

- The main characters attend school in south London. They’re attending a party in East Croydon.

- A maze of streets with ‘narrow houses with rusting cars or bikes in their concreted front gardens’ and ‘the dusty glass fronts of newsagents, which smelled of alien spices and sold everything from birthday cards and secondhand comics to the kind of magazines that were so p*rnographic that they were sold already sealed in plastic bags’.

- ‘Everything looked very still and empty in the Summer’s evening.’

- Eight in the evening, which Gaiman describes as a liminal time of night, along with the liminal time of life — being fifteen-years-old, horny but without experience or confidence. ‘It was eight in the evening, not that early if you aren’t yet sixteen, and we weren’t. Not quite.’

THE SOUNDSCAPE

Neil Gaiman provides a typical 1970s soundtrack. At the time, people like these characters were listening to:

- The Jam

- The Adverts (who supported The Jam)

- The Stranglers

- The Clash

- The Sex Pistols

- ELO

- 10cc

- Roxy Music

- David Bowie

- Neil Young’s Harvest album especially the song “Heart of Gold“

But these alien girls are listening to unfamiliar music which sounds a bit like Kraftwerk, a German band who created futuristic music starting with “Autobahn” in 1974. They were ahead of time in creating music, so I’m not surprised Neil Gaiman referenced them.

Since we’re talking about Kraftwerk, imagine a “robot pop” style which combines electronic music with pop melodies, sparse arrangements, and repetitive rhythms. What’s the modern equivalent? Because if boys from the 1970s heard music from the 21st century they’d be equally bamboozled by it.

So, you might listen to something like this as your story soundtrack. (Crow, DJ-Kicks, by Forest Swords.)

ANALYSIS OF “HOW TO TALK TO GIRLS AT PARTY”

THE ALIEN SETTING

DEFAMILIARISATION

Basically, Neil Gaiman defamiliarises the setting, helping us to see our familiar world in a new way. Storytellers have various ways of achieving this effect. Each writer has their own reason for defamiliarising an audience; in this case, I believe the defamiliarised environment serves to depict that uniquely liminal adolescent experience in which you tip dangerously from childhood into adulthood without supervision. A same-aged peer can’t help you, not really, no matter how confidently his advice.

THE MAZE

Gaiman’s narrator, Enn, describes the roads leading out from the 1970s East Croydon train station as ‘like a maze’. Any fictional description which includes a maze is reminiscent of the famous Greek myth with the Minotaur and we know that the boys will find their way deep into their subconscious, fight a battle with a fearsome creature then make their way out again.

Another story which uses maze-like alleys leading to another world is Hayao Miyazaki’s The Cat Returns — albeit it, in a very different story. (Or is it really that different?)

THE EAST CROYDON EQUIVALENT OF UKIYO

Neil Gaiman is sure to describe the music, the lighting, a garden path with ‘crazy’ paving, a time of day which is neither daytime nor dark. The boys walk past a shop which they now associate with sex because it sells p*rn magazines. Enn recalls a slightly scary incident in which the shop keeper caught Vic trying to steal one.

These boys are trying to work their way into what Japanese culture refers to as The Floating World (ukiyo) — the English-speaking sphere doesn’t have a good word to describe it — that otherworldly, imagined universe of wit, stylishness, and extravagance—with overtones of naughtiness, hedonism, and transgression. The word basically encapsulates the flourishing pleasure-seeking culture which existed in Edo Japan (1603 – 1867).

Importantly, The Floating World is firmly embedded in an urban setting. It is a city within a city, more specifically a sort-of red-light district. By passing the shop with the magazine, the boys are entering a pseudo red-light district.

CREATING A SENSE OF ADOLSECENT ALIENATION

When you’re a young teenager and unused to attending parties with mind-altering substances, and when partnered sex is novel, exciting and also terrifying, the experience can feel like you have set foot on another planet. Neil Gaiman takes this very common feeling and turns it into speculative fiction. What if the people at the party really were from another planet?

Importantly, Enn himself feels like he’s from another planet. He doesn’t feel like he belongs at a party.

- Gaiman introduces the party-alien metaphor like this: ‘They’re just girls,” said Vic. “They don’t come from another planet.”‘

- Next he describes how boys and girls bifurcate into separate ‘species’, or seem to, from Enn’s point of view: ‘And then one day there’s a lurch and the girls just sort of sprint off into the future ahead of you, and they know all about everything, and they have periods and breasts and makeup and God-only-knew-what-else — for I certainly didn’t. The diagrams in biology textbooks were no substitute…’ Notice how when the alien girl shows Enn her bifurcated finger, this is a visual representation of how boys and girls seem to separate around adolescence. (This binary way of thinking about gender doesn’t take account of genderqueerness, but via social media Neil Gaiman has since revealed himself to be an ally.)

- Gaiman takes a very common ice-breaker, “Are you from around here?” so that, in an example of delayed decoding, readers can look back and laugh at the understatement of the girl shaking her head.

- Of course, all of these strange conversations are reminiscent of talking to someone who is high. People on psychedelics can go off like this. The Psychedelic era was the time of social, musical and artistic change influenced by psychedelic drugs, occurring from the mid-1960s to mid-1970s. The era was defined by the proliferation of LSD. Enn responds to the incomprehensible things coming out of the alien girl by simply constantly bringing the conversation back to Earth. He’s not interested in anything she has to say because he’s not there to hear her talk. Any communion is purely phatic when the real goal is a sexual experience.

- The strange girls are, in some ways, a mirror of the strangeness Enn feels himself. For example, the girls speak with a strange accent with strange grammar. Enn himself is young and trying a little hard to impress. When he uses the word ‘contradictory’ he puts emphasis on the wrong words. One reading of this story: The girls at the party represent the boys’ fear of sex, which comes entirely from within themselves. Being fifteen, but posing as older young men (drinking Pernod, trying on confidence like a coat), they’re not actually read for sex. It’s just that their libidos are driving them to it. Like any fifteen-year-old, they need protecting, partly from themselves.

- The beauty of the girls is overwhelming to Enn, who doesn’t feel at home in his attracted state. For Enn, senses are heightened. The blonde girl isn’t simply blonde, her hair is white. Her eyes aren’t big, they’re huge. ‘they had whatever strangeness of proportion, of oddness or humanity it is that makes a beauty something more than a shop window dummy.’

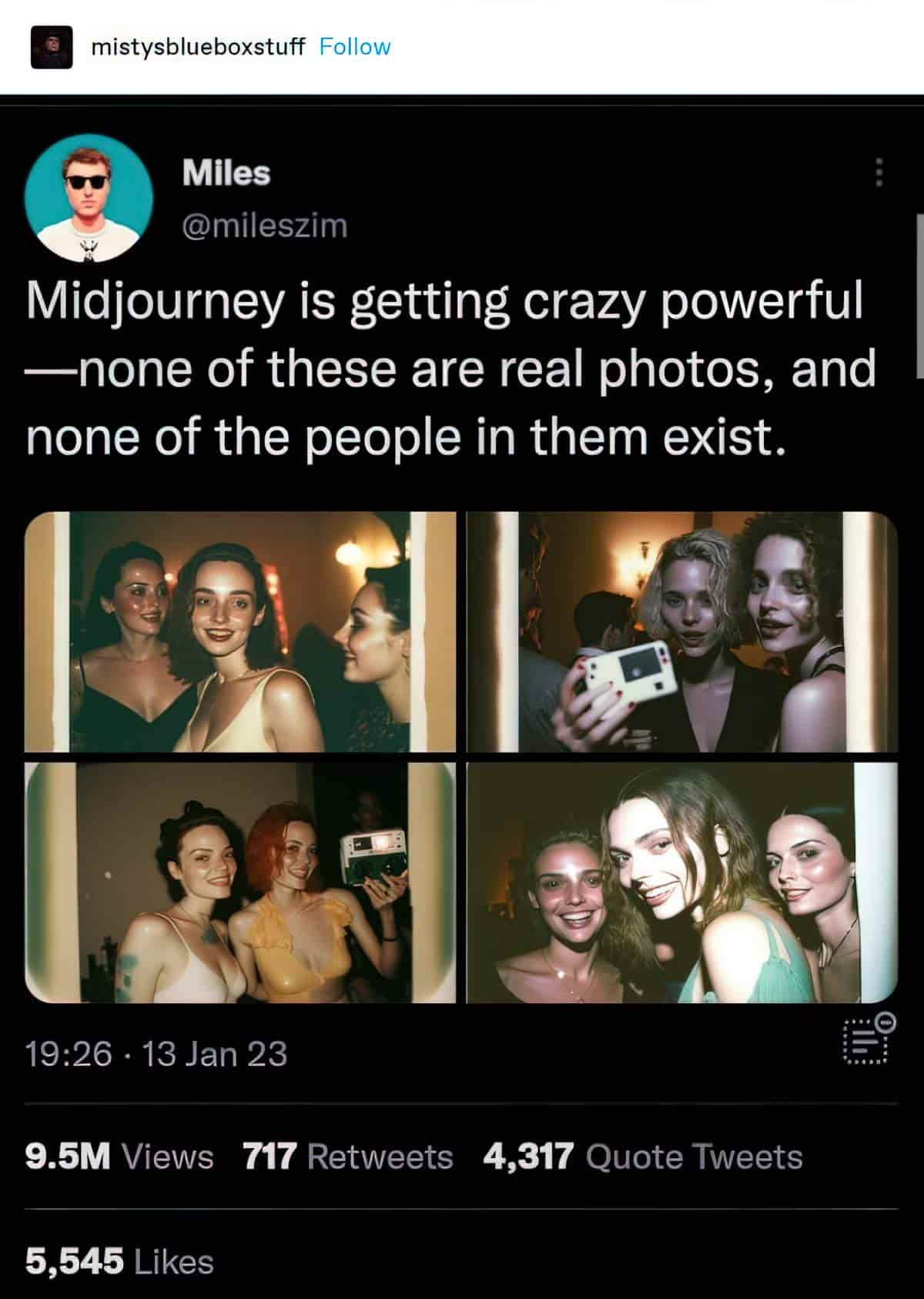

Neil Gaiman has created a party reminiscent of 2022 Midjourney images (an AI art generator powered by Stable Diffusion.) When first released, the Stable Diffusion model would make a reasonable job of landscapes, but when it came to humans? Extra fingers, extra teeth. Eyeballs off-centre. At first glance, the images looked fine, but on closer inspection, many fell into the uncanny valley of creepy.

THE ENDING

Readers, like Enn, never find out what happened to Vic upstairs with the alien girl. But we know it’s sexual, that Vic is freaked out by it, and the alien’s mask is off. Since everyone at that party was apparently female, it’s likely the aliens have no gender at all, they have simply chosen the bodies of young, alluring women to function as femmes fatales. In any case, Vic thought he was getting one kind of experience and ended up getting another.

The two boys walk home together but alone. There’s now a rift between them and, since Vic never did tell Enn what happened, we can deduce things will never be the same between them. Whatever happened has left Vic traumatised. And because boys are only permitted to express a narrow range of negative emotions — chiefly anger — that’s how Vic responds. He’s angry. Anger gives way to tears when the boys are on their own. Now he’s a little boy again. He went to the threshold and wasn’t ready for it.

This is a far too common experience for young people who go to the literal or metaphorical ‘upstairs’ during parties.

Note that Vic has urged Enn, his less suave protégé to “talk to girls” and also “listen to them”. Sage advice. Except Vic’s own gift-of-the-gab hasn’t saved him. Nothing will save you from sexual assault when another person has ill-intent.

Illustrations for this article were created using Stable Diffusion (SDXL).