Here’s an example of the floating camera technique opening a novel by Marian Keyes:

June the first, a bright summer’s evening, a Monday. I’ve been flying over the streets and houses of Dublin and now, finally, I’m here. I enter through the roof. Via a skylight I slide into a living room and right away I know it’s a woman who lives here. There’s a femininity to the furnishings — pastel-coloured throws on the sofa, that sort of thing. Two plants. Both alive. A television of modest size.

The Brightest Star in the Sky by Marian Keyes

Irish author Marian Keyes continues to describe the inhabitants of a small block of Dublin flats at 66 Star Street via the viewpoint of a ghostly entity with a sense of humour who can compress itself into a shoe if it wants to. This supernatural entity is able to see into the memories of everyone in the building.

It’s worth mentioning that many long-time fans of Marian Keyes struggled with this unusual point of view, which they found creepy. (Readers pick up a Keyes novel for light-hearted humour, albeit often with dark themes.) Lesson learned. We can put this viewpoint to good use if we’re wanting to create a creepy, ominous atmosphere.

Like in a crime novel, for instance. Dennis Lehane is an American crime writer who opens a novel in similar fashion:

The power goes out sometime before dawn, and everyone at Commonwealth wakes to swelter. In the Fennessy apartment, the window fans have quit in mid-rotation and the fridge is pimpled with sweat. Mary Pat sticks her head in on Jules, finds her daughter on top of her sheets, eyes clenched, mouth half open, huffing thin breaths into a damp pillow. Mary Pat moves on down the hall into the kitchen and lights her first cigarette of the day. She stares out the window over the sink and can smell the heat rising off the brick in the window casing.

Small Mercies by Dennis Lehane (2023)

There’s nothing in the content of the opening to Small Mercies which suggests Ominous Creepy Vibe. It’s hot. There’s a power outage. A woman is about to make a cuppa in the kitchen (or try to). The floating camera is creating atmosphere for us.

But what is so creepy about this roving, floating camera viewpoint? As an amateur amateur amateur evolutionary biologist (not really), I have a Theory.

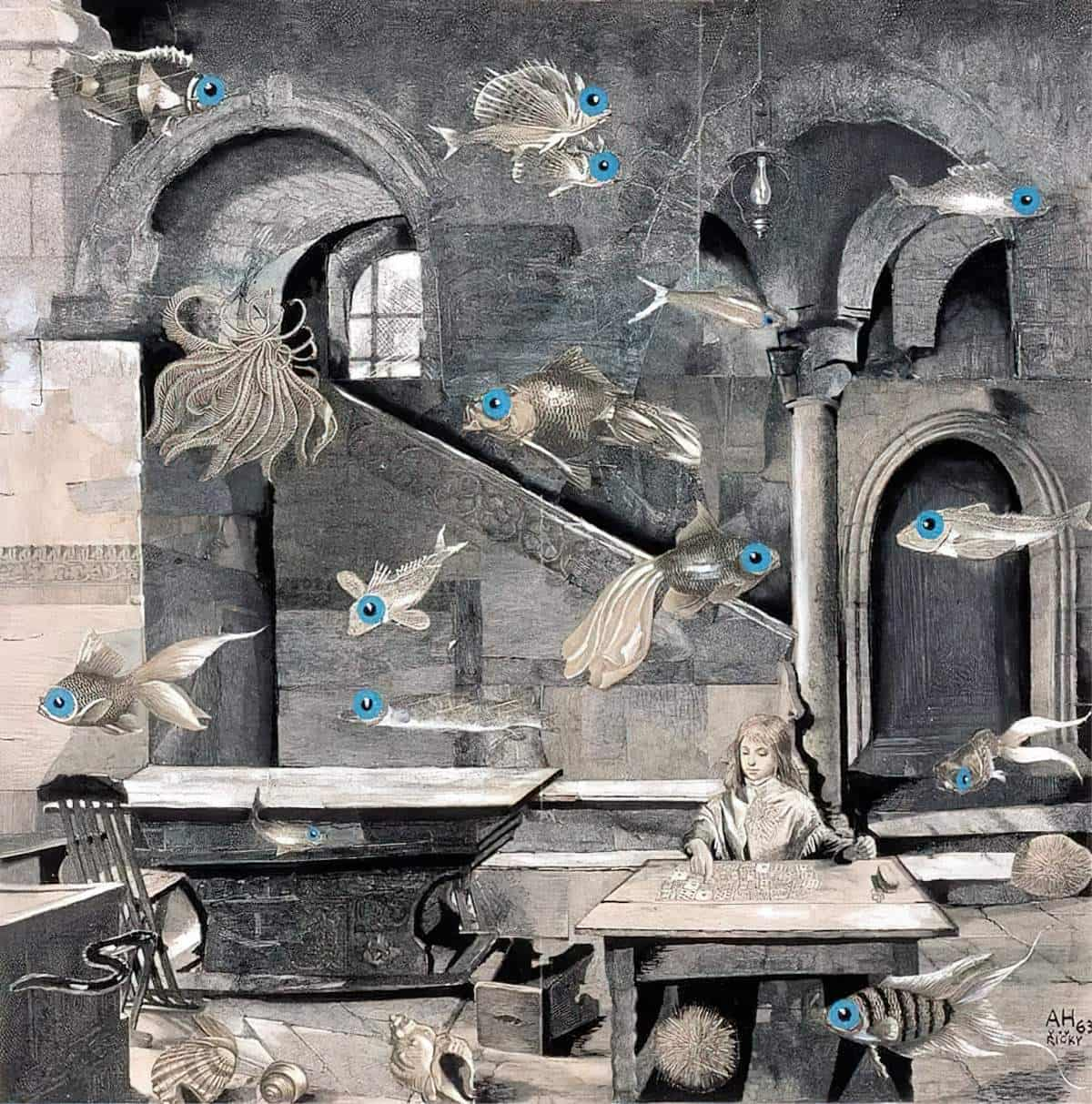

We remember when we were fish. Yes. Fish. Little fish swimming underwater, on the constant lookout for big fish who might eat us. This narrative ‘fish-camera’ is swimming through the fluid of air. (Yes, air is a fluid.) Our connection to the ocean is mostly lost, until we look for it. Then we see it frequently in stories.

If my fish theory doesn’t work for you, let’s stick with the ghost theory. It wasn’t so long ago pretty much everyone believed in ghosts. Many still do. This narrative technique has a ghostly feel to it. Something is watching. It’s invisible.

For another literary example take The Tricksters, a 1980s New Zealand novel for young adults — a ghost story set by the sea. A family gathers in a haunted house. Below, different members of the household think they feel a presence. Notice what the ‘camera’ does:

In the kitchen, Naomi wrapped cheese in a plastic bag, put empty bottles down beside the fridge and put new bottles in to chill. An ordinary, pleasant, unexciting Christmas is what we need, she thought, and then–who knows? “Wet towels on the verandah rail!” she said aloud, reminding someone she felt come into the room behind her, someone smelling of the sea. However, when she turned around, the kitchen was quite empty.

Emma, sitting with Tibby, drowsy at last and almost asleep, thought Naomi was looking in at the door.

“What’s so strange about it all is that it really feels like coming home,” she said uncertainly. “I thought it might have changed.” There was no reply. “Are you absolutely sure it’s OK for me to be here, baby and all?” She turned, but the room and the doorway were both empty.

Suppose, thought Harry, sitting at her peaked window, suppose I was accidentally welcoming someone through when I took that hand.

The Tricksters by Margaret Mahy

The ‘camera’ has focused on Naomi in the kitchen. Next paragraph, Emma sitting with Tibsy. Then, Harry sitting at her peaked window. The invisible entity has moved seamlessly through the house, across the ground floor, up to the attic. It’s subtle, but the effect is real. Readers now feel that the house is haunted.

Ocean Metaphors In Crime, Horrors and Thrillers

Now I want to look at some examples of this on TV. As everyone is very visually literate now, I believe authors have taken this technique from film directors (though it’s probably a technique which has evolved simultaneously, in tandem).

Broadchurch

The best example I have seen is Broadchurch. The director soon dispenses with this technique but the opening is all that’s needed to create that ominous vibe.

The fish metaphor works here because this is a community set beside the sea. Introductory imagery melds sea and (not-so-) cosy cottage together. Post-processing has given the scene a bluish hue, not only to replicate night-time but also to emphasise the underwater blues of the ocean.

Another early sequence of the pilot episode shows an eerie but cosy seaside little town, and the camera floats along the main street of this village in a smooth, floating, creepy fashion, as if a ghost. Or a fish. The fish (camera) follows one of the main characters creepily down the street, offering contrast with the friendliness of the storybook village. The camera might be a fish or might equally be an invisible ghost.

Panic Room

The camera in Panic Room floats through the house, first along the floorboards then up and over, through objects and walls, waiting for the Jodi Foster character to discover her dangerous intruders. The story opens with the camera floating around New York City, establishing the location as Manhattan.

The trailer of Panic Room gives an idea of how the camera moves.

And here’s the ‘camera fish’ moving from a scene in the film:

THE FALL

British detective series The Fall is an interesting case. Below is a clip from the pilot episode, in which the camera is positioned from the point-of-view of an omniscient eye (as given to the audience) but moves like a predatory fish underwater. Note that the camera is following the villain in this case, not the potential victims. That’s because The Fall is not a whodunnit, or even a whydunnit. Suspense for the viewer in this case relies upon watching how the hero detective (Stella) solves the mystery of a serial killer.

I highly recommend using the floating camera technique when writing ominous, creepy stories. It works really well. But beware of accidentally making a cosy scene ominous by floating from place to place, character to character!

Header illustration: Adolf Hoffmeister, V souhvězdí ryb, In the Constellation of Pisces, 1963