**UPDATE LATE 2024**

After Alice Munro died, we learned about the real ‘open secrets’ (not so open to those of us not in the loop) which dominated the author’s life. We must now find a way to live with the reality that Munro’s work reads very differently after knowing certain decisions she made when faced with a moral dilemma.

For more information:

My stepfather sexually abused me when I was a child. My mother, Alice Munro, chose to stay with him from the Toronto Star

Before Alice Munro’s husband sexually abused his stepdaughter, he targeted another 9-year-old girl. ‘It was a textbook case of grooming’ from the Toronto Star

So, now what?

Various authors on CBC talk about what to do with the work of Alice Munro

And here is a brilliant, nuanced article by author Brandon Taylor at his Substack: what i’m doing about alice munro: why i hate art monster discourse

“The Flats Road” is a short story by Canadian author Alice Munro. This story opens Munro’s 1971 collection Lives of Girls and Women. The school board in Munro’s native Huron County banned this collection from the Grade 12 syllabus.

Because this is a banned book, you should definitely read it.

Why was it banned? Because as poet Muriel Rukeyser once said:

What would happen if one woman told the truth about her life? The world would split open.

Fittingly, opening story “The Flats Road” is all about how people go to great lengths to conceal the traumatic truth of women’s lives. Normatively married women are so often complicit, as a self-preservation instinct.

Some have said that Lives of Girls and Women is not a collection of short stories at all, but a novel in chapters. All of the stories feature the experiences of a woman called Del Jordan and her life coming of age in a small Southern Ontario town called Jubilee.

THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN A NOVEL AND A COLLECTION OF LINKED STORIES

Garth Greenwell had this to say about his second book Cleanness when asked if he intended it as a novel or a collection:

I hope the nine chapters are like spheres of intensity that are placed in a relationship that is not the consequence of plot or the linearity of chronology, but is instead a kind of constellation, that there are charged relationships between them that is like a key change, or a mood, or an echo, or a motif.

The Guardian

I believe what Greenwell said about Cleanness can apply to many collections of short stories which fit together in the same story-world, utilising the same cast of characters. It certainly fits Alice Munro’s Lives of Girls and Women.

Munro has herself explained how she sees stories architecturally, as a house whose various rooms one can roam in and out of, forgoing any prescribed order.

THE COLLECTION TITLE

Before the book was published, it was going to be called Real Life. The reason it wasn’t called that: another book (by Deborah Pease) was coming out around the same time, and publishers wanted to avoid confusion. The original title of Munro’s collection points to the realism. Alice Munro was going for stories which feel realistic and true to life.

THE STORY IN A NUTSHELL

It is approaching the beginning of WW2, summer holiday, though there’s no sniff of wartime yet.

Young Del Jordan is a rising Grade Four girl, spending much of her time near the local river with her younger brother and also with the eccentric, childlike man known as ‘Uncle Benny’, who works for their father on the family fox farm.

One day, 37-year-old Uncle Benny decides to advertise for a wife in the personals section. He asks young Del to compose the letter as he dictates. This is before the Internet, of course, which changed everything.

Within a week he is driving to a nearby town and comes back married the very same day. But he’s embarrassed to introduce his new wife.

Eventually it is revealed that the wife is at least 20 years younger than himself, barely an adult, in fact. Madeline is an unkempt, skinny harridan who causes nothing but drama around town.

Young Del had always enjoyed visiting Benny’s house because she likes to read the salacious newspapers he keeps stacked on his veranda (along with many other bits of rubbish in his hoarded-up old house).

But now the young wife, Madeline, won’t let Del near, yelling at the girl to keep away. Her own little girl seems overly timid, and will only engage with Benny, not even with her own mother.

Madeline, as it turns out, causes such a ruckus around town that she becomes the new local ‘madwoman’, replacing the status of another elderly woman also known as the local madwoman of down-and-out Flats Road.

Eventually Madeline leaves town with her toddler and a few of Benny’s precious but worthless things, at which point Benny decides to reveal that Madeline was abusing her own little girl all that time. This explains the bruises everyone noticed but didn’t ask about.

After receiving a letter from Madeline wanting some left-behind items posted to her new address in Toronto, Benny decides to retrieve the girl in person, kidnapping be darned. He’ll save the little girl from her abusive young mother.

But when driving in the city for the first time, Benny is overwhelmed by the busyness of the roads, doesn’t understand the road rules, doesn’t know to buy a map, and never locates her. He returns home after spending the night sleeping in the car near factories and eventually finding his way out of the labyrinth.

Afterwards, Jubilee locals, including Del’s mother, who was initially so concerned about child (toddler) welfare she wanted police involved, decide (because it’s easier) that Benny was probably lying about the child abuse anyway. In absentia, Madeline lives on in Jubilee as a colourful story about Benny’s temporary madwoman wife.

Modern readers will understand that Madeline was herself an abused child, and that her behaviours were a trauma response. Feminists will recognise the age-old tendency to describe women as ‘mad’ or ‘crazy’, because it replaces a narrative which is far more difficult for people—especially other women—to stomach: That women’s lives are not as valuable as men’s; that some women bear the violent brunt of this reality; and that terrible, terrible intergenerational traumas are happening to other women as we speak, mostly behind closed doors.

As you read, look for various ‘troubling distorted reflections’, a phrase Alice Munro uses towards the end of the story.

UNCLE BENNY

Uncle Benny—no blood relation, but the guy who works for the dad—is an eccentric whose ideé fixe is a part of the Wawanash River where he spends much time fishing. He recounts tall stories about the river which the children (one of them our narrator) remain skeptical about, even as children. Uncle Benny insists there are deep holes in the river, as well as a dangerous patch of quicksand. He lives in a shack near the river surrounded by rescue animals and partially tamed ones. This isn’t because he’s especially empathetic towards them. He keeps turtles to sell to an American, apparently for turtle soup. The American never shows up.

This character is reminiscent of the wild, psychotic man who lives in a hole in the ground in “Images” (Dance of the Happy Shades). However, this family arrangement is far more similar to the one described in “Boys and Girls“. In this later story, Uncle Benny sits down to eat at the table and pastes his chewing-gum to the end of his fork. Henry was the character who did this exact thing in “Boys and Girls”. Both of these men show their gum to the children and ask them to admire the pattern. Alice Munro has returned to something she knows well: growing up on a fox farm, recapitulating the characters into a new story with new names.

Uncle Benny still lives in his natal home, never having moved out. His parents have died, leaving Benny to become increasingly hoarded up. He likes to rescue detritus from the dump, imagining he’ll put the rubbish to some use. These days we call this hoarding disorder. Trash hoarding is a fairly common type. Other types include: animal hoarding (also Uncle Benny), book hoarding (he hoards newspapers) and food hoarding. Health problems associated with hoarding include: depression, psychotic disorders and obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). Hoarding can start a number of months after a massive and catastrophic loss, such as divorce or death. In short, Ben is sorely in need of a housekeeper. He needs a life manager. I’m sure his mother would have played this role before she died, and now some of this burden has shifted onto Del’s mother. Understandably, Del’s mother would love to see Del married to a good woman.

THEMATIC INTRODUCTION: SALACIOUS NEWS AS ENTERTAINMENT

The children see Uncle Benny’s cluttered house as a sort of playground. The narrator finds a pile of newspapers, the kind which existed to fill in the need for salacious news before Jerry Springer came along. She spends hours over summer reading these, skeptical of their truth, but finding them fascinating anyway. As for Uncle Benny, these salacious, untruthful papers are his only window on the outside world as he doesn’t read the mainstream papers. Nor does he listen to the radio.

The existence of this 1970s short story shows how even before the Internet, it was possible to become radicalised by immersing yourself in attention-grabby trash-news.

But no one needs newspapers and Internet before turning people’s personal lives into entertainment. Even without those things, there are always local eccentrics, down-and-outs, harridans… Such people have their narratives constructed for them. Why? So that they remain Othered. So the normative families can rest easy, believing themselves to be nothing alike.

AN ASTUTE YOUNG NARRATOR

Despite being young, the narrator is astute. (We don’t yet know her name, suggesting Del has not ‘come into herself’.)

When Uncle Benny tells young Del she is allowed to take the newspapers home with her, she knows better than to do that. Either Uncle Benny would miss them once they are gone, or her own parents would never allow her near such reading material. She is at a developmental stage where she is thinking a lot about what’s true and what’s not. (Many middle grade books for children deal with this theme.) While at Uncle Benny’s trash heap of a house, she is able to believe those trashy headlines are real. But as soon as she approaches her own sensible, mainstream home, she is pulled out of the fantasy. In this way, Uncle Benny’s house is akin to a fantasy realm, almost magical, but in a very dark way. Already she understands the ‘truth’ of a situation is hard won, because adults have their own reasons for telling stories about themselves and, in this story, others.

DEL’S MOTHER

The children’s mother isn’t too happy to be living on Flats Road, feeling herself above the type of poor people who live there. However, she does have sympathy for the ‘genuinely’ downtrodden (negroes, Jews and so on). Where her empathy runs dry is at drunkenness and lewd behaviour. This common empathy gap shared by people who consider themselves kind is explored by writer Mike White in season one of the TV series White Lotus. Big sister Olivia sneers at her younger brother, who she has labelled autistic, but will stand up for people of colour, the LGBTQ community, and anyone else she knows to be marginalised but doesn’t personally know.

DEL’S FATHER

Del and Own’s father is far more at home on Flats Road and happy to have a friend like Benny (Benjamin Thomas Poole), who is no blood relation of the narrator’s family.

Modern parents may note with interest that 1930s children were permitted to spend so much time with a man like Benny, but in the 1930s (enduring into most of the 20th century) it didn’t cross people’s minds that some adults can be sexually interested in children. So it’s not all that strange that the children would be spending so much time at ‘Uncle’ Benny’s house, fishing with him along the river. (I doubt Alice Munro’s 1970s readership would have thought much of it either; trust changed in the 1980s, which you can track alongside the dramatic drop in men registering to become primary school teachers.)

UNCLE BENNY FINDS A WIFE

Munro has spent much time evoking the setting of this story. I really feel the vibe of 1930s Jubilee. Now readers get to the meat of the story, in which it will become clear that not a single one of those set-up details was superfluous, or included purely for scene-setting purposes. Alice Munro’s details always do double (or triple) duty.

One day after midday dinner at the Jordan farmhouse, Uncle Benny asks the young narrator to write him a letter. He can read well but he can’t write. This combination of splintered literacy skills is far less common these days, but until recently was the norm. Even as far back as the middle ages, it was common for the masses to possess the skill of reading, but rare to possess the skill of penmanship.

Benny is responding to a woman (‘lady’) who has an ad in the personals. She’s looking for a position as housekeeper for a farmer. If he so wishes, marriage can be part of the deal. Rather than try and sell himself, he tries to sell her on the lifestyle. Readers have already been introduced to Benny’s hoarded-up old hovel, so we see the irony of the description, which is true nonetheless. Benny makes the place sound like a rural utopia, surrounded by berries and fresh fish, ample firewood for winter. All of these things are simultaneously true.

IT’S ALL IN THE DETAILS

It’s especially masterful how Alice Munro likened the down-and-out houses on Flats Road to images from the Bible by noting the similarity between children’s Bible illustrations and the various animals all kept together. In Bible illustrations this technique has narrative purpose (aside from illustrating the actual plot of Noah’s Ark), but when poor people keep their chickens in the yard alongside their cows, it only signals lack of land, lack of farming knowledge, lack of general organisation and self-determination.

Anything can sound good if you embellish with the right details. (Who knows this better than a professional writer?

The reply comes swiftly. The woman, Miss Madeline Howey had her brother write the letter. It would seem she’s a single mother of an eighteen month old daughter, without means of supporting herself.

It’s unclear at this point whether Madeline herself even wants to be married off, though it becomes more clear later. It soon becomes clear that the brother has arranged this whole thing, to avoid the burden of another mouth to feed. This is an instance of run-of-the-mill local human trafficking.

THE COMPLICITY OF ORDINARY FOLK

Alice Munro shows how ‘regular’ families like the Jordans are complicit in this trafficking scheme.

Munro has already reminded us that these were tight times via the men’s conversation at the dinner table, as they ‘joke’ about finding a woman with good teeth, and weigh up the pros and cons of a fat wife versus a skinny wife. BMI doesn’t matter so much as finding a wife who doesn’t drain your finances by eating a lot. They agree it’s impossible to tell from body size how much a woman eats (a lesson which seems lost on contemporary readers, after decades of diet culture).

Still, Del’s father isn’t astute enough to realise this may be the reason why a brother may want his sister married off. Just as likely, he doesn’t care, because a man is entitled to arrange the marriage of a sister.

Instead the father first wonders if there’s something wrong with the woman. As is the case in a number of Munro stories, a misogynist fear is subsequently ‘proven correct’, because the nature of misogyny is this: Expectations themselves cause reality in a complicated fatalistic way.

Nor does it occur to Del’s father that it would be a shock to arrive at Benny’s pit of a house, barely habitable, full of rubbish, surrounded by various wild animals. When Del’s mother decides to spruce Benny’s place up in time for the bride’s arrival, only then does she realise that Uncle Benny might be a terrible catch. Unlike child Del, whose childlike status affords her the omniscience of a roving camera, the mother hadn’t realised the state of Benny’s house.

THE ROLE OF SEXIST ‘JOKES’

So we’ve seen how at the dinner table, men joke about the expense of wives (even as a wife sits right there, having to listen to it).

Freud said there’s no such thing as a joke, that a joke is an expression of veiled hostility.

These men may have been ‘joking’ about having her teeth pulled out, and also her appendix and gall bladder while they’re at it, but this was no joke. My own grandmother and great auntie, born in the early 1920s, both had their teeth ripped out at the age of 17 to make them more ‘marriageable’. When I say ‘ripped out’, I’m not using hyperbole. This was common practice in New Zealand, and I expect it was also common practice in Canada as well. Boys were exempt because they were expected to earn a living and maintain their own damn teeth. But girls had perfectly healthy teeth removed and replaced with full dentures to save their future husbands any expense. This was part of the deal fathers made with potential sons-in-law. Women were literally chattel. This isn’t five hundred years ago. This is one hundred years ago.

And frankly, some people still think like this.

There was no anaesthetic for the removal of teeth. My grandmother was born the same year as well-known New Zealand author Janet Frame. If you watch An Angel at My Table, directed by Jane Campion, there’s a scene in which this happens to Janet.

Like Janet Frame, my grandmother was traumatised by the experience. She never removed her false teeth in front of anyone, and when I once asked her about the experience as a child she simply shook her head and pressed her lips together. This was very unlike my loquacious grandmother.

Men joke about women (and women joke about husbands) because jokes render the uncomfortable comfortable.

Jokes establish in-groups and out-groups, reassure us that we’re simply conforming to a cultural norm, and also let us Other those who ought to garner our sympathies.

THERE IS NO BINARY OF GOOD WOMEN, BAD WOMEN: ONLY AN UNCOMFORTABLE CONTINUUM WITH HOUSWIFE IN THE MIDDLE

Alice Munro has also made sure to mention the town whorehouse when creating the setting of Jubilee. Why? She’s guiding readers to make a link in our minds: There’s the disreputable demimonde of Jubilee, and then there is a ‘completely separate’ category of women who are advertised not as sex workers, but as the ‘respectable’ equivalent: housekeepers willing to marry if sex should be required as well.

Munro underscores the hypocrisy of this distinction by lingering on how the letter to ‘the lady’ should be addressed. Is this a personal letter or business? the grade four narrator asks. Both, comes the reply.

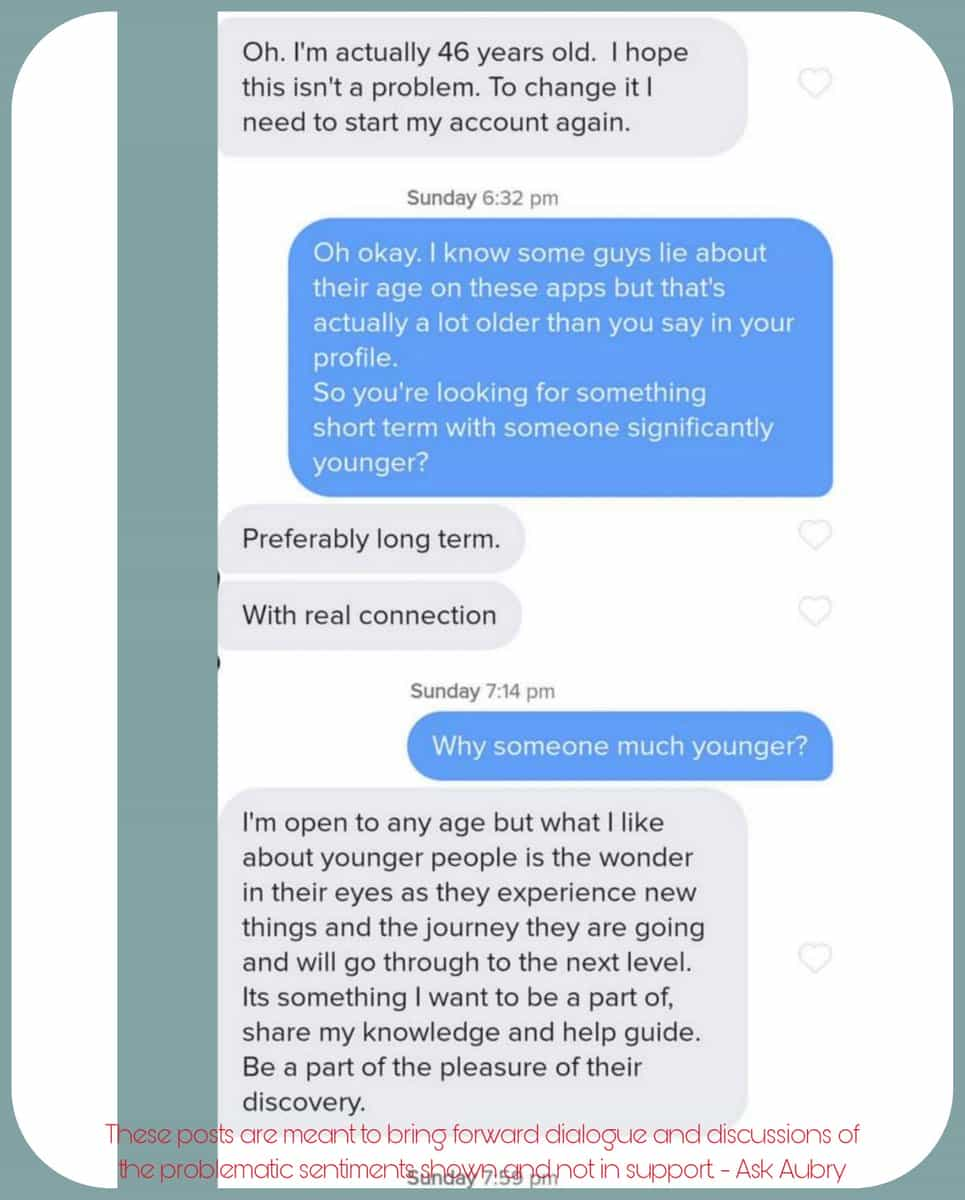

For discussion: Where do the “girls” in the example below fit in the continuum between wife and sex worker?

Very Important People: Status and Beauty in the Global Party Circuit

Ashley Mears’ new book Very Important People: Status and Beauty in the Global Party Circuit (Princeton University Press, 2020) provides readers with a closer look at the global party circuit. A lifestyle that offers million-dollar birthday parties, megayachts on the French Riviera, and $40,000 bottles of champagne. In today’s New Gilded Age, the world’s moneyed classes have taken conspicuous consumption to new extremes. In Very Important People, sociologist, author, and former fashion model Ashley Mears takes readers inside the exclusive global nightclub and party circuit—from New York City and the Hamptons to Miami and Saint-Tropez—to reveal the intricate economy of beauty, status, and money that lies behind these spectacular displays of wealth and leisure. Mears spent eighteen months in this world of “models and bottles” to write this captivating, sometimes funny, sometimes heartbreaking narrative. She describes how clubs and restaurants pay promoters to recruit beautiful young women to their venues in order to attract men and get them to spend huge sums in the ritual of bottle service. These “girls” enhance the status of the men and enrich club owners, exchanging their bodily capital for as little as free drinks and a chance to party with men who are rich or aspire to be. Though they are priceless assets in the party circuit, these women are regarded as worthless as long-term relationship prospects, and their bodies are constantly assessed against men’s money. A story of extreme gender inequality in a seductive world, Very Important People unveils troubling realities behind moneyed leisure in an age of record economic disparity. Ashley Mears, Ph.D. is a Associate Professor of Sociology at Boston University.

New Books Network

THE CHILDLIKE UNCLE BENNY

Alice Munro has shown in an earlier short story (“Postcard“) how women are expected to grow up young, enjoy a very narrow window in which they are allowed to be ‘young women’, yet men frequently remain childlike and ‘eligible’ well into their adulthood, despite having been given the mantle of householder and decider of everything.

It is darkly comical that Uncle Benny wants to address the letter “Dear lady”. As mentioned above, Munro has underscored the transactional nature of this marriage, but there’s another reason for it too, darkly comical in its effect.

Uncle Benny’s opener of ‘dear lady’ reminds me of a friend whose three-year-old wanted a drink of water at a café, so his mother told him to ‘go and ask the lady for one’. “Excuse me, lady,” began the three-year-old, embarrassing his mother. Uncle Benny has a similar childlike quality about him, and is hardly marriage material. However, his childlike sensibility makes him attractive to actual children, including the narrator and her brother, and soon to a new child in his life. It is fully expected that no matter how poor he is as a catch, there will always be a woman (or team of women) readily available to rally around him, prop him up.

Imperial states have long realised that men require wives. Taking the example of British governance of the subcontinent, men were required to do the work of empire building. The state recognised that the men wouldn’t last five minutes without women to do their cooking, housework, provide sex and also care for them whenever they took ill. But the state did not wish for European wives to join these men, so they instead made use of local women, in concubine arrangements. The problem was, many of the men fell in love with their concubines, and—in what should have been no surprise to anyone—many ‘mixed race’ children were born. Many of the fathers wished for their children to have a British education, but Britain did not want a whole lot of brown kids, dual-citizen children running around, making it difficult to lump people into easy ‘brown’ and ‘white’ racial categories. Race making is hard work, after all, and needs constant maintenance. Their response was to double down on divvying people into racial categories. In this way, race making goes hand-in-hand with maintenance of the gender hierarchy, with straight white imperialist men at the top.

Back to Ben’s position in “The Flats Road”. If marriage can be this transactional, where does that leave women such as the young narrator’s mother? In the end, isn’t every 1930s marriage a sexual transaction? Where there’s no real gender equality, there’s no real choice. Already we see her living in a place she never would have chosen for herself. Clearly, it was Del’s father who decided they would move to Flats Road and start a fox farm, which suits his temperament well.

This story is not set on the subcontinent, with state arranged concubines. But sex has never been a personal and private thing. For married people, the sex/procreation requirement was (and still is) enshrined in marriage law.

TROUBLING DISTORTED REFLECTIONS

So alongside our world was Uncle Benny’s world like a troubling distorted reflection, the same but never at all the same. In that world people could go down in quicksand, be vanquished by ghosts or terrible ordinary cities; luck and wickedness were gigantic and unpredictable; nothing was deserved, anything might happen; defeats were met with crazy satisfaction. It was his triumph, that he couldn’t know about, to make us see.

“The Flats Road” by Alice Munro

- The disorder inside Benny’s house is a microcosm of the busy, unnavigable city of 1930s Toronto, where Benny gets hopelessly lost. Alice Munro describes both in a similar way, and makes sure the two tie together in readers’ minds by mentioning the quicksand of the Wawanash River and also the ‘quicksand’ as metaphor for city life.

- On a small scale, various carefully chosen details do double duty, e.g. the various animals found in the front yards of poor people, at once indicative of poverty and also of pre-Lapsarian passages of The Bible. (Pre-Lapsarian of course suggests a ‘Post-Lapsarian’ Fall, which is why I choose that word. For women, a Fall from society means permanent stigma, permanent ostracization.)

- The over-riding ‘troubling distorted reflection’ of this story: A married woman and a whore are not so different when women are valued chiefly for their bodies. The difference is purely on paper, a difference in ‘respectability’, and not necessarily reflective of any material difference. This leaves married women such as Del’s mother in a difficult psychological position. It would do her no good to start wondering if she’s no better than one of those Other women, the ‘whores’ she despises. Of course, we despise the most those who aren’t so different from ourselves.

RESONANCE OF “THE FLATS ROAD”

Fast forward to the 2020s. Do we still have a tiered system in which some girls’ lives are more important than others? Hell yeah. Alice Munro’s characters are white, and she explores the way in which socioeconomic status—rather than race —impacts the level of care extended to different ‘types’ of girls.

More recently, various feminists have tried to turn our collective attention to the way in which race intersects with gender.

Let’s take a look at some recent state dealings with groomed and trafficked young women.

THE CASE OF SHAMIMA BEGUM (2015)

Shamima is a British born woman who entered Syria to join ISIL (aka ISIS) in 2015 at the age of just 15, along with two other London schoolgirls, Kadiza Sultana and Amira Abase. Shamina rapidly gave birth to three children. Her children all died. Then, in 2019, Britain stripped Shamina of British citizenship, considering her a terrorist threat.

What if a white British fifteen-year-old had been radicalised? It is likely that, had she been white, the white state would have called the radicalisation what it is: ‘grooming’. Instead, because Shamina is brown, she was framed as a ‘bride’ rather than as a groomed trafficking victim. White people in the UK could rest easy with the UK government’s decision to make her stateless because “that’s what they do, in that culture. Marry the girls off young”.

The UK went against international convention by stripping a citizen of her citizenship, leaving her stateless. If every country did this to ‘disposable’ people, the world would soon turn to disarray.

(This case is British, but there is a Canadian link. It was an intelligence agent—spy—for Cananda who smuggled her into Syria. He shared Shamina’s passport details with Canada as the UK police were looking for her. Also, the problem is worldwide. There is a very similar 2021 case in Australia, in which Australia lumped responsibility for a young Australian woman onto New Zealand, where she also had citizenship. This caused a rift between New Zealand and Australia, as Prime Minister Ardern didn’t see it ethical to simply cancel a young woman’s citizenship, leaving another country to deal with the problem. To make matters worse, in this case, the woman had two children.)

In each of these cases, rich white countries illuminate their own fears: The continuing fear of the sexually deviant woman. The sexuality of women has always been considered dangerous by the state, every state.

In Alice Munro’s story it’s unclear whether “Uncle Benny” is expecting young Madeleine to have sex with him during her stay. His childlike presentation suggests maybe not. He doesn’t seem driven by it, instead drawn to the toddler daughter as a playmate. But even if non-consensual sex is not taking place, we shouldn’t pacify ourselves by thinking, “Well, Madeleine was only a housewife. If so, it wasn’t so bad.”

THE UNCOMFORTABLE IDEA OF THE MODERN “HOUSEWIFE”

Shamima Begum, too, insists that while living in the Islamic state she was only a housewife, doing housework, looking after her own children, in an attempt to persuade the UK that she had not become a terrorist threat. But this didn’t help her out at all, because as well as sympathising with ISIS agendas, now she had said something else contemporary white people find deeply uncomfortable: This idea of the “housewife”, a word which we feel belongs in a previous century due to its connotations of female disempowerment. Shamima had unwittingly pointed out to those in the UK that the Islamic State is, in some ways, not at all different from life in the UK, which is not what British people wanted to hear. They needed to hear that the Islamic State is completely different from ‘us’; we don’t subjugate our women. We don’t expect women to bear our children, to shoulder the bulk of our housework; no, not at all.

It’s worth asking why Shamima Begum felt she could live life as a mother with children in an Islamic country but not make that life choice by remaining in the UK. Radicalisation, grooming and human trafficking is the main reason she ended up in a terrible situation. But perhaps Shamima had taken a close look at house prices, wages, inflation, the lives of women around her in London, the expectation that women do childcare and housework as well as hold down full-time jobs, and came to the not-actually-crazy conclusion that if she wanted to be a stay-at-home mum, fleeing to an Islamic state was a pretty sound career move.

THE COMPLEXITY OF HUMAN HIERARCHIES, TRAUMA & ABUSE

At no point does Alice Munro suggest that the ‘problem of Madeleine’ is easy to solve. There’s nothing Ben can do once the girl leaves. Moreover, what he does try to do is problematic.

As Ulrica Skagert explains, Munro uses the metaphor of getting lost in the city to show the complexities of dealing with Madeline’s situation:

[B]eing endowed with a sense of possibility is by no means an approach to life that one may adopt as one chooses, or for that matter is it a promise of an idealized existence. For all its excitement it includes great risks, and paradoxically also a sense of inevitability.

When the eccentric Uncle Benny, in “The Flats Road,” from Lives of Girls and Women, finally makes the decision to rescue the child from her molesting mother, his failure even to find the right house is disturbing from any commonsensical point of view. Meticulously and truthfully, Uncle Benny describes his efforts to orient himself in Toronto, and how he is constantly blocked from finding the right direction. Any rational argument about getting a map and tracing one’s way by it falls short of covering the complexity of Uncle Benny’s situation. It is paradoxically the acceptance of the impossibility for Uncle Benny to reach his intended goal that reveals an opening of the possible. Having spent the night in his car, Uncle Benny wakes up and intuitively “knew what [he] better do was just get out, any way [he] could get”. This is a truth that obviously cannot be argued. My father sighed; he nodded. It was true.

Ulrica Skagert