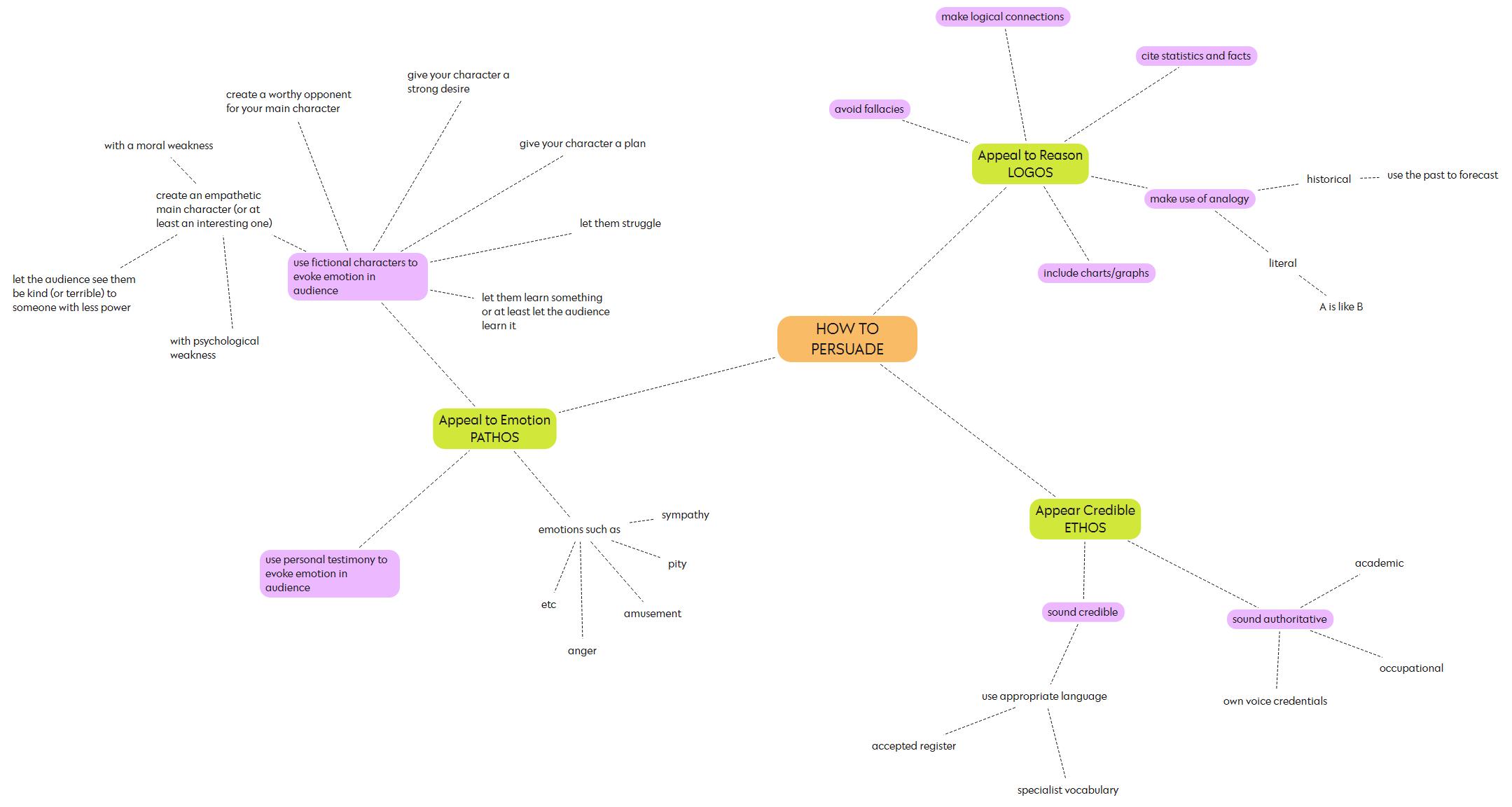

Today, we consider logos one of three main persuasive techniques as popularised by Aristotle:

- ETHOS: The writer makes sure they sound credible.

- PATHOS: The writer appeals to audience emotion.

- LOGOS: The writer appeals to reason.

Examples of persuasive texts:

- advertising (buy this!)

- opinion pieces

- letters to the editor

- speeches to political representatives

- etc.

ETHOS, PATHOS & LOGOS

FICTION RELIES MORE HEAVILY ON PATHOS THAN LOGOS AND ETHOS

Fiction is not a ‘persuasive text’ in the sense Aristotle was talking about. In fiction, making an argument is not the main point.

However, fiction is still persuasive. Fiction isn’t persuading you to buy a new car or to change a particular aspect of law or to vote for a particular party in a certain election, but fiction nevertheless persuades, mainly by means of entertainment. You could argue that fiction is the most persuasive form of text because it persuades at a deeper level.

A good story first persuades readers to keep turning the page. Beyond that, fiction persuades readers to think about big ideas — themes — and what it means for humans to lead a decent life.

LOGOS IN FICTION

Fiction writers know a lot about pathos — how to evoke emotions in their audience. But some types of story benefit from persuasive techniques more akin to logos.

For example, in cosmic horror, a fictional narrator may be doing their best to persuade the audience that such-and-such unbelievable thing really happened. In this case, the author may make use of fictional statistics, charts and maps.

Fiction authors may also make use of real-world statistics, charts and places on real maps in an attempt to blur the boundary between reality and fiction, creating an immersive, perhaps terrifying experience for the audience.

Other forms of storytelling deliberately set out to convince audiences that a fictional story is true, namely tall tales. Tellers of tall tales will frequently make use of logos, appealing to logic, before illuminating the gullibility of the listener in a game of one-upmanship.

A number of literary traditions descend from the tall tale tradition. Gulliver’s Travels almost fits into the category. Mark Twain was a master. Also, the potboiler Western is full of the type of braggadocio which requires the initial suspension of disbelief on the part of the audience.

EXAMPLE FROM LITERATURE: RIP VAN WINKLE

Washington Irving’s Rip Van Winkle draws heavily from German folk tale and makes use of fictional logos to persuade us that the story of a drunkard falling asleep in the woods for a couple of decades really happened. Of course, the audience is expected to understand that this travel memoir is allegorical satire. The author makes use of a story-within-a-story technique, in which the fictional narrator apparently came upon the papers of a fictional historian called Diedrich Knickerbocker.

The following tale was found among the papers of the late Diedrich Knickerbocker, an old gentleman of New York, who was very curious in the Dutch history of the province, and the manners of the descendants from its primitive settlers.

Rip Van Winkle by Washington Irving

This is an author of fiction mimicking persuasive techniques of logos (making use of found documents) to ease readers into an immersive story. To use different language, Washington Irving is creating verisimilitude (the appearance of being true or real).

Irving is also making use of (parodied) ethos, because Diedrich Knickerbocker supposedly knows what he’s talking about. (The ridiculous name is the wink which tells us not to interpret this story as fact.) Then we’ve got the story of poor Rip Van Winkle, with the awful wife. (Largely married, male) audiences are expected to empathise with poor Rip. This is Washington Irving making use of pathos.

If you’re reading a story which opens with a lengthy description of place, social customs, or lists many details, you’re being asked as a member of the audience to imagine this place and time really exists. Once you’re in this almost hypnotic (alert but hypnagogic) mental state, you’re primed to be affected by the main persuasive technique of the storyteller: pathos.

MORE ON THE ORIGIN OF THE TERM LOGOS

Logos is a loaded term among philosophers. Physician, philosopher, poet and novelist Raymond Tallis wrote a book called Logos, and believes pre-Socratic philosophers came up with it first. It was probably invented by a philosopher called Heraclitus.

Christianity embraced it and popularised it.

Humans make sense of the world using a whole range of tools:

- sensory experiences

- exploratory techniques in the search of principles

- looking for laws that go beyond mere patterns

- etc.

According to Tallis logos is, in a sense, our sense.

Our sense-making capabilities and the relationship between our individual and collective intelligence and the comprehensibility of the world is both remarkable and deeply mysterious. Our capacity to make sense of the world and the fact that we pass our lives steeped in knowledge and understanding, albeit incomplete, that far exceeds what we are or even experience has challenged our greatest thinkers for centuries.

In Logos, Raymond Tallis steps into the gap between mind and world to explore what is at stake in our attempts to make sense of our world and our lives. With his characteristic combination of scholarly rigour and lively humour he reveals how philosophers, theologians and scientists have sought to demystify our extraordinary capacity to understand the world by collapsing the distance between the mind that does the sense-making and the world that is made sense of. Such strategies – whether by locating the world inside the mind, or making the mind part of the world – are shown to be deeply flawed and of little help in explaining the intelligibility of the world. Indeed, it is the distance that we need, argues Tallis, if knowledge is to count as knowledge and for there to be a distinction between the knower and the known.