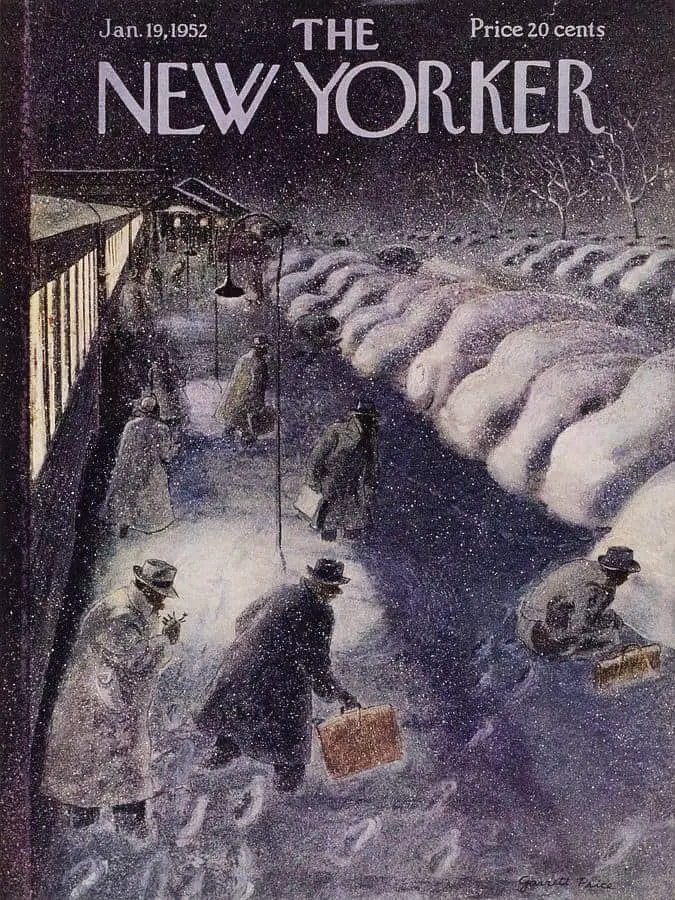

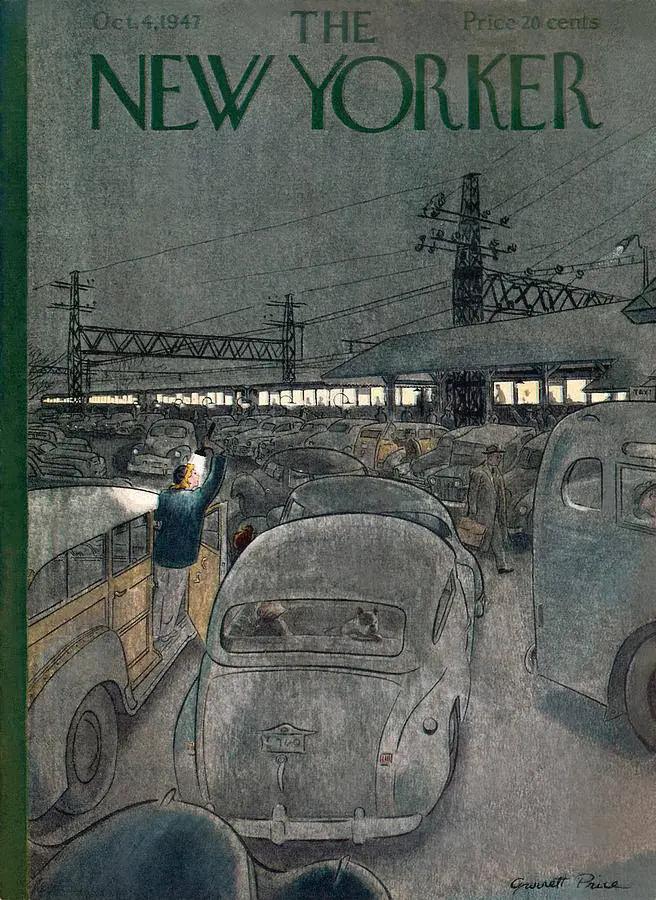

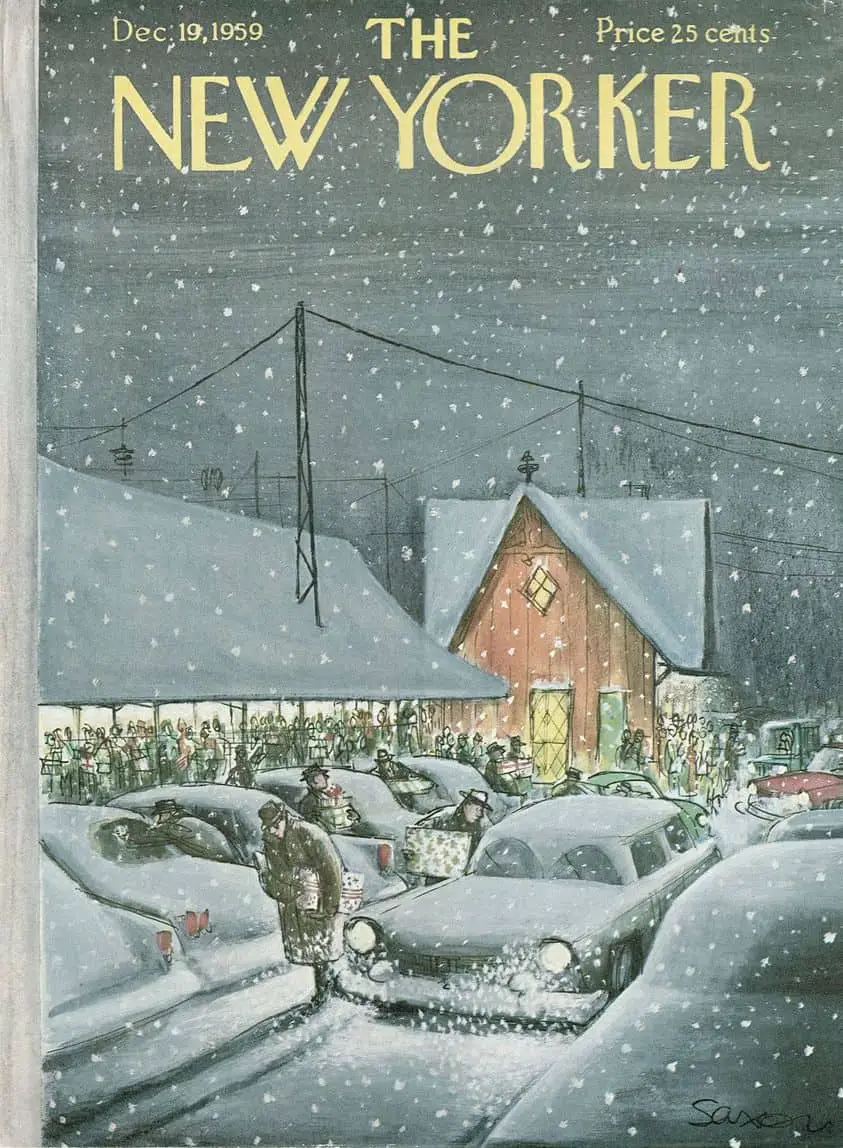

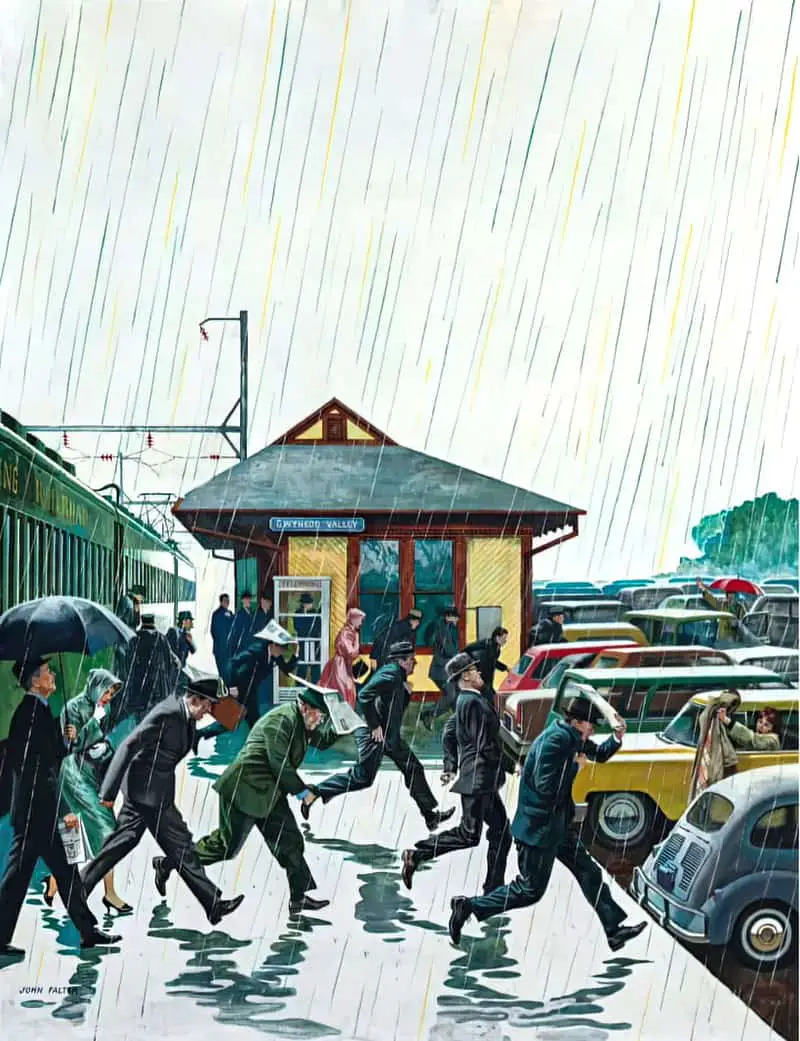

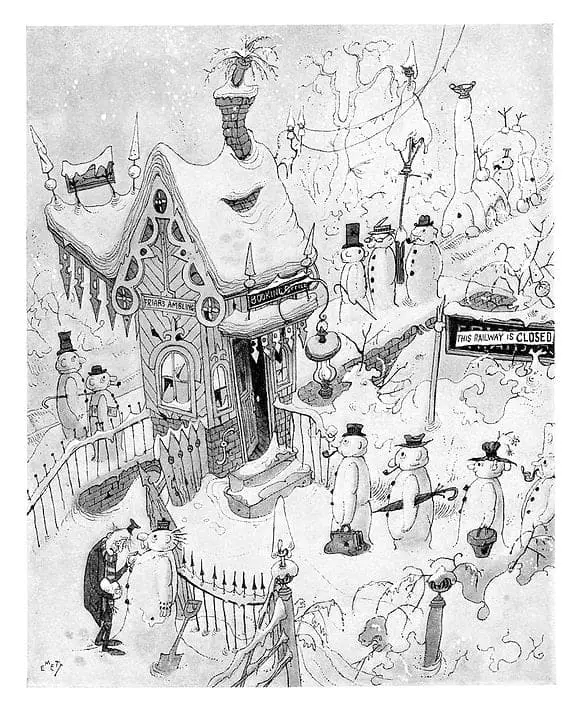

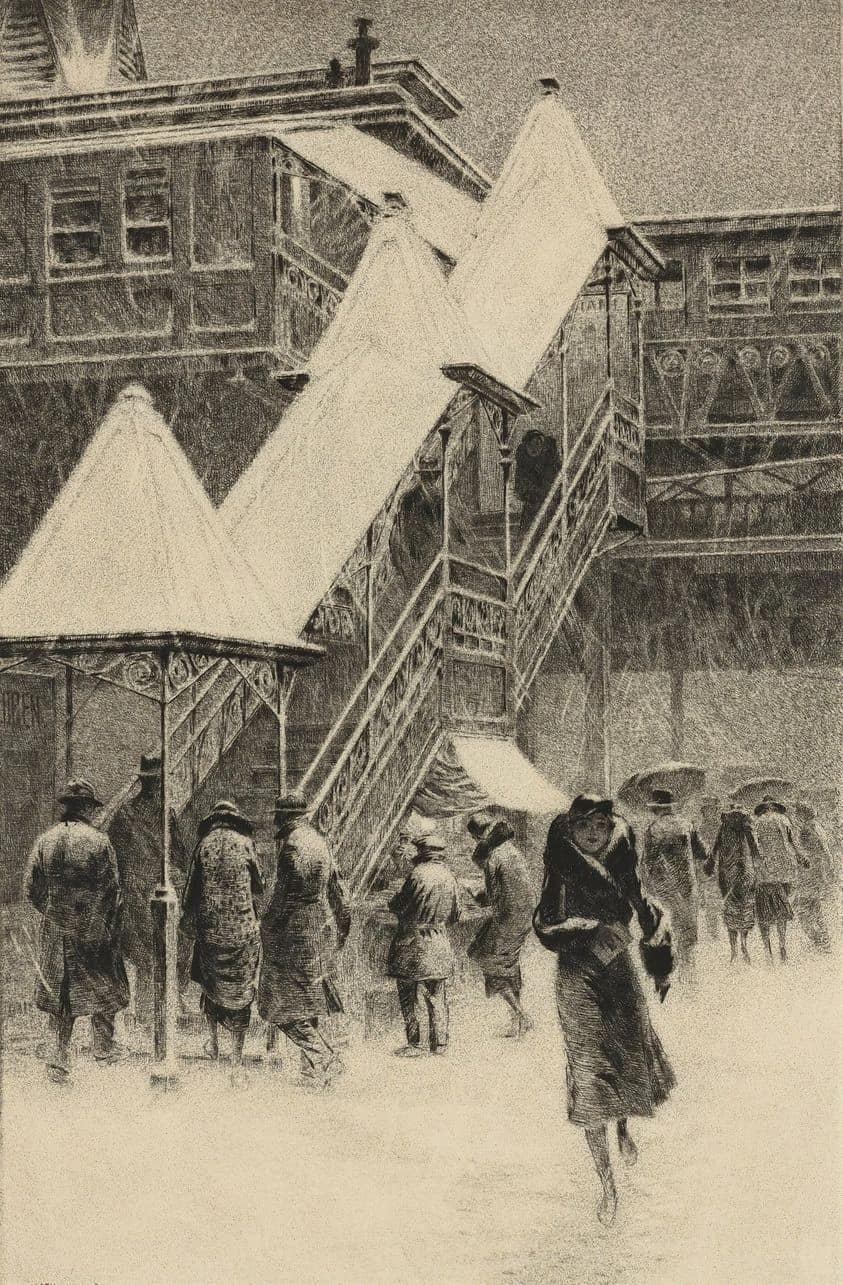

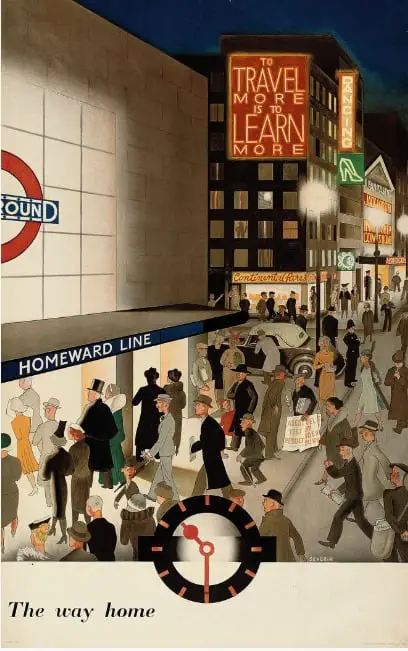

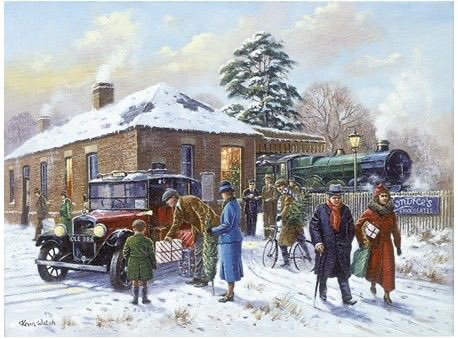

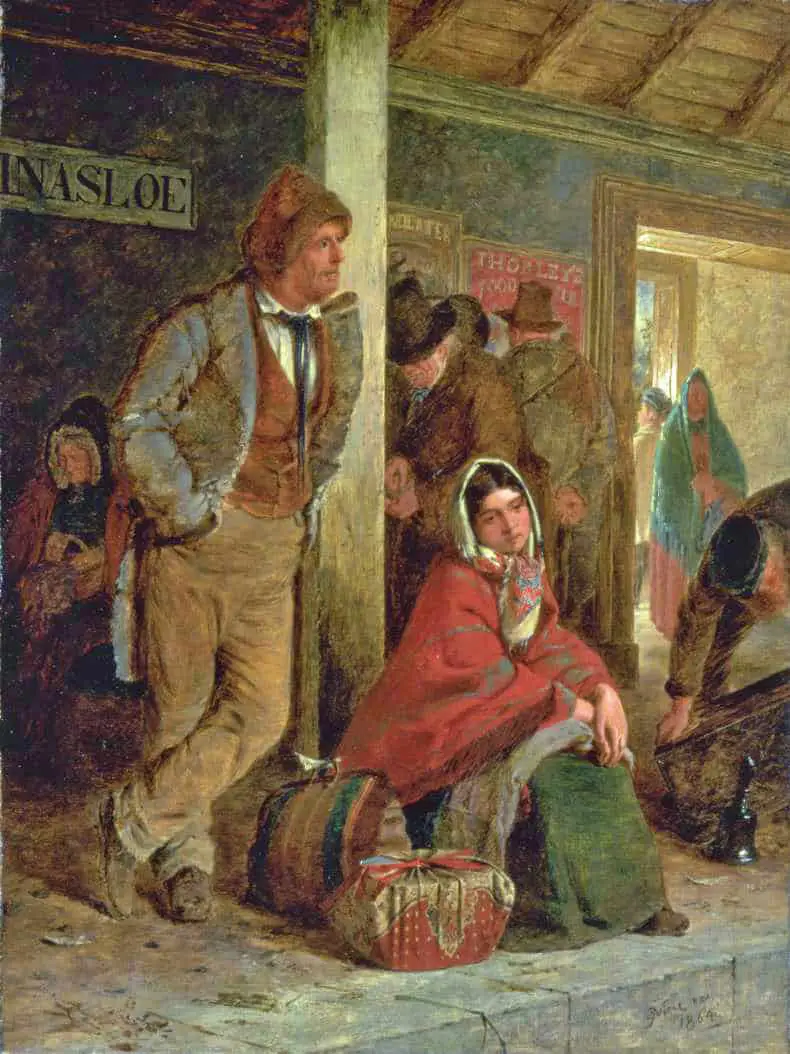

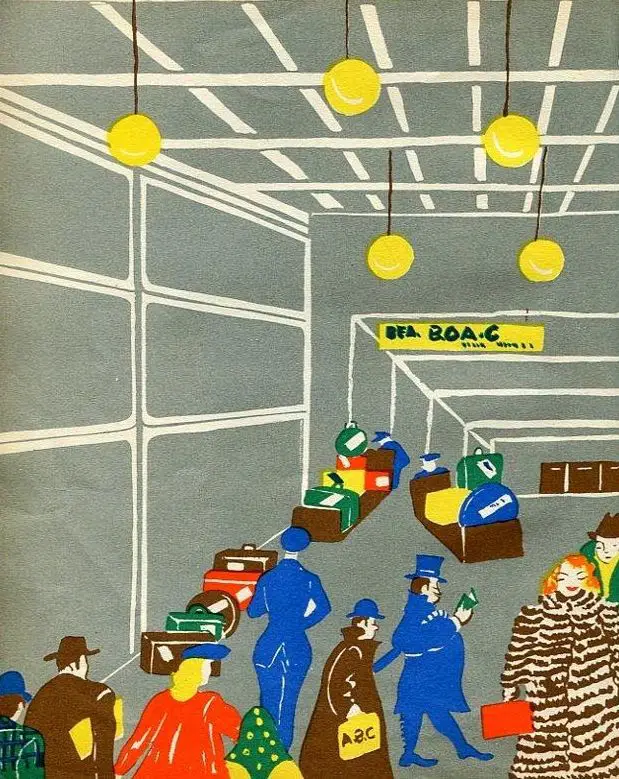

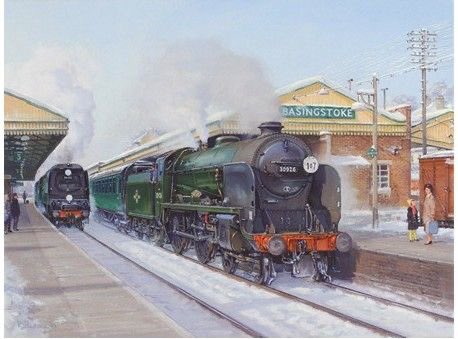

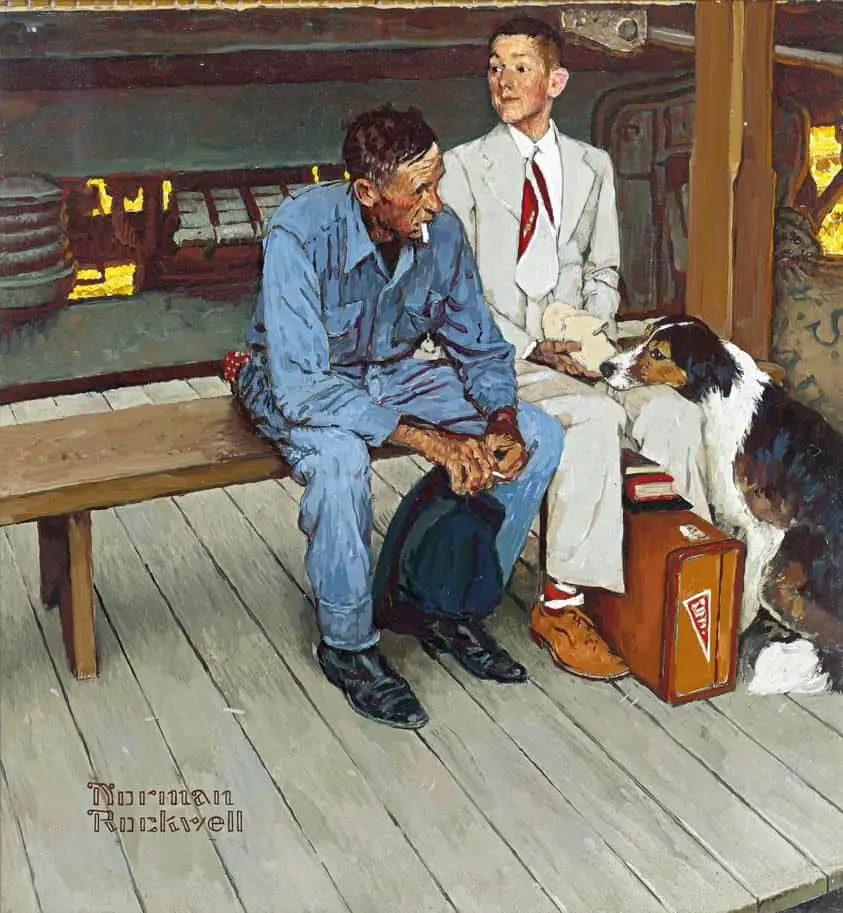

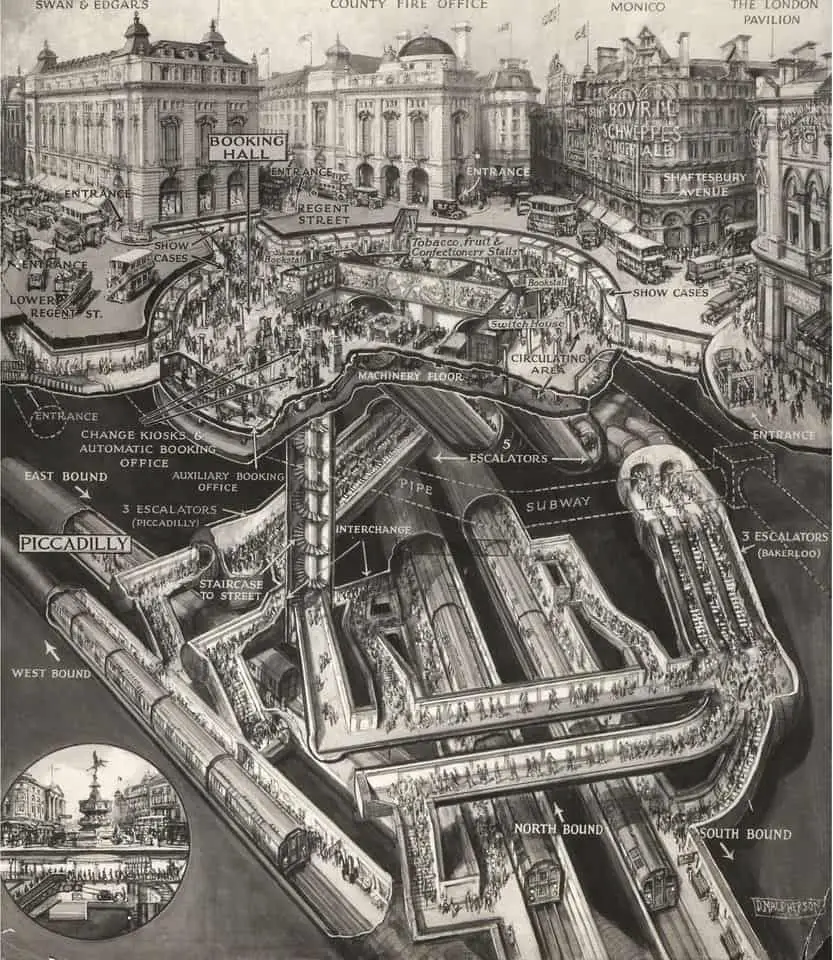

These illustrations are views of the outside of commuter stations — train stations, lorry transfer stations. (I’m not including here illustrations of the insides of commuter stations.)

Commuter stations are interesting because they fall into the category of ‘liminal spaces’. When creating stories, writers are typically advised to avoid the transit scenes. This is good general advice, because “Transit can make for a slow and ordinary beginning unless something quite odd is going on or we have an entertaining voice“.

On the other hand, these spaces are such ‘nothing’ spaces that if storytellers and artists linger with purpose, showing the details normally overlooked as we rush from place to place in our daily lives, the description of a commuter station can defamiliarise the everyday experience of living.

Train stations aren’t what they used to be. Take a look at a few then-and-now photos of European and American terminals and you’ll notice a few things beyond the usual observations of technological innovation and increased patronage. First, the grandeur of the older stations has made way for more sterile architecture, as in the cases of St. Pancras and Roma Termini. Second, and perhaps more importantly, the interiors of modern stations bear an uncanny resemblance to shopping malls. Gone is the notion of the train station as a transient space: no more in and out; no more creaky, dark corridors – a proliferation that can only conclude with in-station condos – but somewhere within the riff raff, terminal newsstands still provide a small window into the world of a literature they came to define.

Rethinking The Littérature De Gare: Crime Fiction In France And The U.S.

FURTHER READING

Lost in the Transit Desert: Race, Transit Access, and Suburban Form

Increased redevelopment, the dismantling of public housing, and increasing housing costs are forcing a shift in migration of lower income and transit dependent populations to the suburbs. These suburbs are often missing basic transportation, and strategies to address this are lacking. This absence of public transit creates barriers to viable employment and accessibility to cultural networks, and plays a role in increasing social inequality. In her book Lost in the Transit Desert: Race, Transit Access, and Suburban Form (Routledge, 2017), Diane Jones Allen investigates how housing and transport policy have played their role in creating these “Transit Deserts,” and what impact race has upon those likely to be affected. Jones Allen uses research from New Orleans, Baltimore, and Chicago to explore the forces at work in these situations, as well as proposing potential solutions. Mapping, interviews, photographs, and narratives all come together to highlight the inequities and challenges in Transit Deserts, where a lack of access can make all journeys, such as to jobs, stores, or relatives, much more difficult. Alternatives to public transit abound, from traditional methods such as biking and carpooling to more culturally specific tactics, and are examined comprehensively. This is valuable reading for students and researchers interested in transport planning, urban planning, city infrastructure, and transport geography.

interview at New Books Network

Header illustration: Liverpool Street Station by Edward Bawden, colour lithograph, 1961