This Shirley Jackson short story goes by two titles. Penguin decided to call it “A Visit” for their 2013 Dark Tales anthology, reverting back to the 1952 title. But for about half a century various publishers decided to call it “The Lovely House”. Yes, this is a haunted house story. But — surprise! — this beautiful old mansion isn’t exactly “lovely” once you scratch the surface.

First things first, this short story is a mood. If you’re after hermeneutical closure, look for a plot driven narrative. With this Shirley Jackson story, you won’t know for sure what’s real and what’s not because you’re not meant to. You’re supposed to be left discombobulated. Reading this story is like waking up the morning after a big night out. Ask your friends what happened. Piece it together. But never really know the ‘truth’ of what’s going on.

GOTHIC TROPES IN “A VISIT”

(What does Gothic even mean in relation to literature? No one can agree, but here’s a shot.)

Since Shirley Jackson’s stories are deemed American Gothic, let’s have a stab at listing Gothic features of “A Visit”. No matter how we define it, this short story is indisputably Gothic:

- a virginal maiden main archetype (Carla Montague) who looks after the young girl who is not a romantic rival (Margaret)

- the hero of the story (the brother) has escaped the feminine by escaping the home, and is in danger of being pulled back into it with all the talk of renovations, so he makes a hasty escape

- the villain (Paul?) and with the two men we possibly have a ‘super-male’ and a ‘shadow-male’ (as described by Joanna Russ)

- a big old house with (pseudo?) medieval architecture and ‘ruined opulence’

- a creepy noble family

- separation (a visiting friend from her friend, and before that from her own off-the-page mother)

- a mad woman in the attic (actually a tower)

- a buried, ominous secret (never made clear to the audience)

- maybe some kind of vampiric immortality going on

- a slightly dangerous budding romance, maybe with a dude who isn’t even real — love transformed into fear

- a feminised house (with pretty tapestries and tile mosaics and so on) — the Gothic relies on the feminine

- Characters within an American Gothic are affected by things like the night and their surroundings. An example: A character is in a maze-like area. The story makes a connection between the outer world of incomprehensible path, and the maze-like confusion (inside the character’s mind).

- forces normally repressed are expressed near the end of the story, with characters getting cranky about possible house renovations

- full use of the senses (including spatial horror), with the main character seeming to sink into the actual tapestries at times

- Much gothic fiction is founded on a central mystery. When a story’s main dynamic is to have the protagonist find out something, or realize something that’s been true for some time, the story’s narrative drive comes from the finding out, not in the discovered fact itself (and in fact we never find out)

PRE-READING DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- Have you ever stayed as a guest at the house of a friend (or relative) who is much more wealthy than yourself? What was that like?

- Have you ever been inside a big old mansion? Can you think of big old mansions from TV shows and movies you have seen? Of those, where would you most and least want to live?

- Do you get a different feeling in old buildings and places than in new ones? Can you describe the difference?

MY WEALTHY BEST SCHOOL FRIEND AND HER BIG OLD HOUSE

RICH BEST FRIEND

I had a best friend at intermediate (New Zealand’s version of middle school) who joined our class after returning from a year-long world trip with her family. Emma’s parents were medical professionals, though I realise now there was probably also inherited wealth. The family went skiing every weekend over winter, so I knew they were wealthy. I also wanted to go skiing at the weekend, though when I eventually won a ski trip in a radio competition, I realised I didn’t really like skiing after all. Really, I wanted to be wealthy like my friend. I wanted to say I’d been skiing, to leave one of those lift-pass tags on my jacket and wear it to school.

FIRST PLAYDATE

Eventually I was invited for a playdate at Emma’s house. The family lived in the most expensive part of town. Emma’s house had a long driveway with play equipment in an expansive front yard under majestic trees. The house itself was old and restored and huge, with a grand entrance. All three daughters were musically gifted. When the father came home from work as a paediatric specialist at the hospital he went straight to the piano and played Andrew Lloyd Weber songs from memory. I remember a second piano in the conservatory, a welcoming messy kitchen, sprawling living areas. Despite the undoubtable wealth, ordinary things happened in this home. Emma’s five-year-old sister was baking a cake, left the metal spoon in the mixture, broke the microwave. That was the sort of crap that happened at my house.

LOSING MY SENSE OF SPACE

Later, I was surprised to learn the family property extended even beyond the back fence, opening onto a lawn tennis court. Beyond the tennis court was another fence and another large garden.

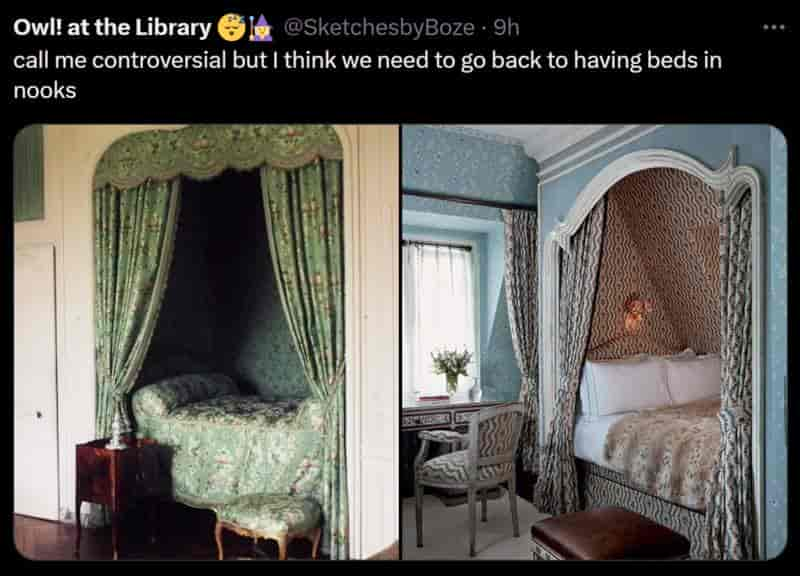

Here’s the weird thing. After showing me around her family home that first time, Emma took me to her bedroom. I couldn’t believe it. Whereas her sisters occupied large rooms with high ceilings and big windows, Emma slept in a literal closet.

At my own house, my brothers and I all fought for the largest bedroom, which wasn’t much larger than the others. To be relegated to a closet would have felt a massive blow.

CONFINEMENT — THE DAUGHTER IN THE CUPBOARD

But Emma told me she had chosen the closet as her bedroom. She could have had one of the large rooms, but preferred the cosiness of the closet, which was literally the size of her single bed. She kept her clothing in drawers under the bed. Her possessions were arranged neatly on a built-in shelf.

Unlike the girl in Shirley Jackson’s story, I never had a sleepover at Emma’s mansion, though on her twelfth birthday a small group of us spent the rainy winter evening playing games in a small library with a fire and wing-backed chairs. The ‘drawing room’, I suppose. All that space, yet my best friend craved closeness. Closed doors. Warmth.

Looking back, I can see that when a child has so much space, a closet for a bedroom might seem like a welcome respite. We can apply that to other aspects of human psychology, too — shopping for bargains at a thrift store is a completely different mindset when you have enough money to buy new. Moving from your parents’ house into an environmentally friendly tiny home is a happy choice only when you have the option of moving into something larger should you wish or need to.

ANOTHER CUPBOARD

I lost contact with Emma when she was sent to an expensive girls’ high school and I was sent to the local public high school. My public high school was a good one, and offered opportunities I wouldn’t have had at the private school. But I do remember one day in winter when it was literally snowing. The wind chill made it worse. Even so, our class was kicked out of our home room because a boy from another class had broken a window by slamming it, on two separate occasions. (A design flaw beyond our control — school windows should never be slammable, especially not from the outside.)

So my high school best friend and I walked around our expansive, cold school until we found an unlocked cleaner’s closet. We spent a grim lunchtime in there, eating our sandwiches to the aroma of that pink gritty cleanser we were required to use ungloved at the end of each year to wipe remove graffiti from desks.

On those occasions I did sometimes think of the peers who went to the private schools. Emma’s girls’ school offered year level lounges with vending machines and hot lunches from the cafeteria. Parents would have complained had their children been turfed out into the literal sleet.

WHAT HAPPENS IN “A VISIT” BY SHIRLEY JACKSON

PART ONE

- Margaret and Carla Montague are on summer vacation.

- This summer, Margaret is visiting Carla at the Montagues’ home. (In French, Montague means ‘steep mountain’.)

- The Montague house is lavish, huge, old and set in expansive grounds. There’s an actual tower.

- There’s at least one tapestry hung in every room. Every tapestry has a picture of the house on it. In Europe, the great period of tapestry weaving ran from the second half of the 14th century to the end of the 18th century. Basically, you know you’re in a very old house when you’re surrounded by ancient tapestries. Henry the Eighth (who murdered his wives) had 2,000 of the damn things.

- Margaret meets the family and is on her best behaviour, keen to make a good impression. She says the right thing. The conversation is very scripted and expected and boring.

- I suppose Margaret is not an uncommon name but still, weirdly for this young Margaret, she finds a tiled room with a mosaic of a girl. The caption: “Here is Margaret, who died for love.” Ominous much?

PART TWO

- Margaret has been wanting to meet Carla’s older brother, the Captain. This guy has a creepy look about him, according to Margaret.

- Eventually the Captain turns up. He’s brought a friend of his own, Paul.

- (Like the Neave family in Katherine Mansfield’s “An Ideal Family“) the Montague family does not feel complete until the son of the household turns up. Once the Captain arrives home, a feeling of familial completeness descends upon them all.

- The four young people spend time together in various parts of the house and grounds.

- But Carla isn’t impressed when her invited friend Margaret starts acting odd, according to Carla. Margaret has been pairing off with Paul, but it’s possible Carla can’t see Paul. She never interacts with him in the story. Perhaps only Margaret can see Paul, in which case Carla thinks Margaret has been spending time alone, talking to herself.

- One day, Margaret and Paul are down by the river. (Ghost?) Paul reveals to Margaret that the family has an elderly female relative living in the tower. The old woman stays up there because she can’t stand the sight of the tapestries. Paul doesn’t know if this woman is an aunt, a great aunt or even older than that. He doesn’t seem to have a handle on linear time.

- Margaret decides to go up into the tower and meet the old woman.

- The old woman’s name is also Margaret.

- Young Margaret is creeped out by this old “woman in the attic” and is keen to get out of the tower.

PART THREE

- As a farewell to their son, the Montagues hold a ball.

- Turns out the old lady in the tower does occasionally leave the tower because she shows up for the ball.

- This gets super confusing for Margaret. Overhearing the conversations, it would appear the old lady and Paul are reminiscing about the old days, with the implication that the two of them were young at the same time. But Paul is a young man, the old lady is positively ancient.

- The ball ends. Over dinner, the Captain points out that the big old house is in need of various repairs.

- Nope. The family isn’t having that. No repairs. The house must stay exactly as it always has been.

- Next morning. After breakfast. Paul and Margaret in the drawing room. Paul is miffed about what the Captain said about the repairs, and doesn’t bother saying a proper goodbye to Margaret.

- The family says goodbye to the Captain.

- REVEAL: We haven’t actually been told until the end that the Captain is Carla’s brother.

- NOT REVEALED: What do the two Margarets have to do with each other? How is Paul connected to the Margarets? Is Paul real or a ghost?

THE TAPESTRIES

Narrative art is art which tells a story. This house is full of tapestries, full of narrative art, full of stories.

There are various different kinds of narrative art, depending on whether it’s framed or unframed, whether characters are repeating and so on.

I put it to you that when Shirley Jackson crafted “A Visit”, she was creating a literary version of ancient narrative art.

TYPES OF NARRATIVE ART

- Monoscenic — represents a single scene with no repetition of characters and only one action taking place

- Continuous — Continuous narrative art gives clues, provided by the layout itself, about a sequence. Sequential narrative without frames.

- Sequential — very much like a continuous narrative with one major difference. The artist makes use of frames. Each frame is a particular scene during a particular moment. Think comic strips.

- Synoptic — offers the synopsis of a bigger story. You must know a story before you can understand synoptic narrative. In a picture book, the text will help with this.

- Simultaneous — has very little visually discernible organisation unless the viewer is acquainted with its purpose. There’s an emphasis on repeatable patterns.

- Panoptic — depicts multiple scenes and actions without the repetition of characters. Think of the word ‘panorama’. ‘All-seeing’ (pan + optic)

- Progressive — a single scene in which characters do not repeat. However, multiple actions are taking place in order to convey a passing of time in the narrative. A progressive narrative is not to be interpreted as a group of simultaneous events but rather a sequence that is dependent on its positioning on the page. Actions displayed by characters in the narratives compact present and future action into a single image.

We don’t know what kind of narrative art we are looking at.

When looking at this scene, is that person supposed to be the same character doing something different, or is that another character altogether?

It would seem Jackson has literally made copies of some of the characters. It would seem Margaret exists in this story both as a young version and as an elderly version of herself. If she is the same person, this is an example of Progressive Narrative Art.

Reading this story is as incomprehensive to us as looking at ancient tapestries. Each century (each generation?) has its own visual literacy specific to itself. Looking at the scenes Jackson paints for us in “A Visit”, we don’t know for sure whether a character is a different iteration of the same person, or someone else entirely.

Note that when we are very young and are learning to read picture books, we don’t initially understand whether a scene such as the one below is the same child or many different children:

In contrast, this image is of many different children and each is a different person:

This is a type of visual literacy which we all must learn. We learn it before we realise we’ve learnt it. But Margaret has been thrown into this ancient environment and has no idea how to interpret what she sees.

SHIRLEY JACKSON’S HAUNTED HOUSES

Jackson’s most famous haunted house story is a novel, adapted numerous times for film and TV: The Haunting of Hill House. This isn’t just Jackson’s standout Haunted House Story, but is considered one of the main classic examples of a Haunted House Story, helped along by the publicised adulation of Stephen King. Jackson was a master of the subgenre.

But instead, I’m inclined to compare “A Visit” to a lesser-known Shirley Jackson work: “The Bus” (1965). Find both stories in the Penguin anthology Dark Tales.

“THE BUS” AND “A VISIT” COMPARED

- An old woman called Miss Harper goes on a night journey by bus. She’s dropped off in the middle of nowhere. Rain is pouring down. She gets soaked.

- She seeks refuge at a hotel in a dodgy place called The Rickets.

- This all takes place over a single evening and night — ostensibly — but the night goes on interminably. Both “The Bus” and “A Visit” seem to feature characters stuck on loop in a cycle of young to old and back again. Some of the characters of “A Visit” could be young and old at the same time. (For younger readers, this is what ageing feels like. The older self co-exists with memories of the younger self, and so old people are young, middle-aged and old all at once.) In science fiction, this is known as time-slip.

- The hotel at The Rickets looks very much like the house of Miss Harper’s childhood — she is both young and old in this house.

- Whereas the message of “The Bus” seems to be ‘there’s no escaping death’, a contradictory message which might just as well apply to both stories is this: ‘Stuck in a life on repeat is a fate worse than death’.