Body swap stories are as ancient as story itself. Take the British folk tale The Witch-hare of Cleveland. A local witch tells some farmers where to find a hare they can hunt, but warns them not to set a black dog on it. They set a black dog on it, of course. That’s how fairytales work. (Someone tells you not to something, you gotta do it. In fairytale language, this warning is called the ‘interdiction’.) Anyway, the farmers go to apologise and find the poor old witch writhing around with a chunk out of her leg… right where the black dog bit the hare.

Is that a body swap story, or is it a simple transmogrification story? Not clear. The story doesn’t tell us if the farmers still have themselves a juicy hare for dinner.

Whether we’re talking about body swap or transmogrification, why are these tales so popular? Body swap stories are high concept stories, and their popularity endures. Freaky Friday, for example, started in 1976. We keep seeing new versions.

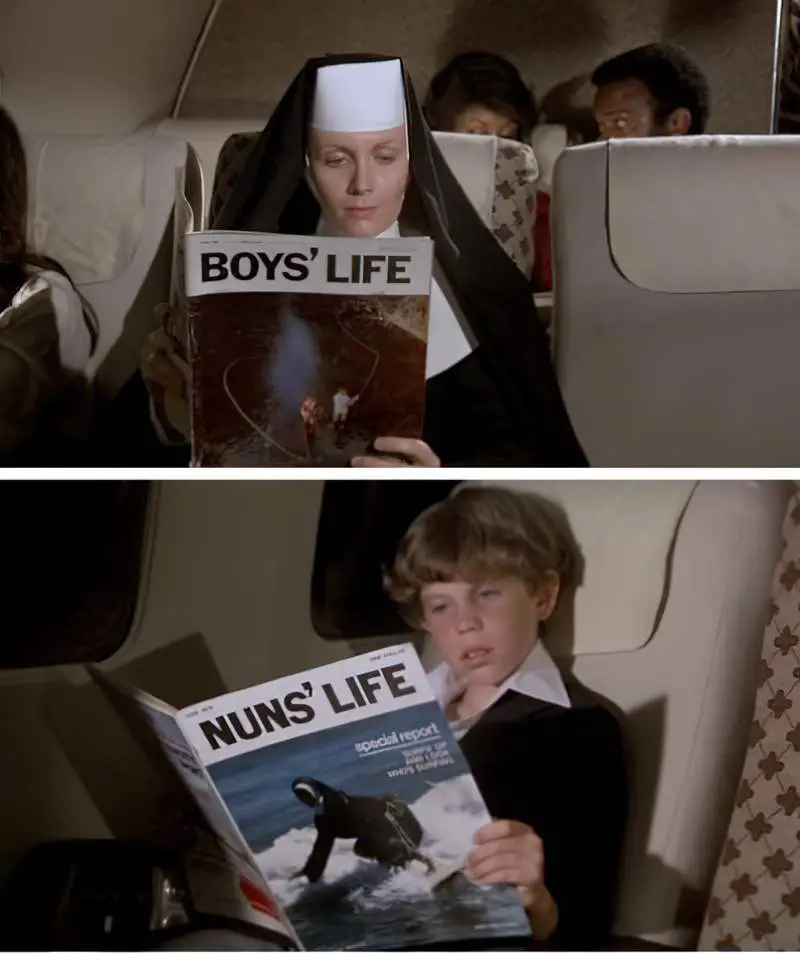

The mother-daughter body swap is relatively ‘safe’ and the moral lesson is clear: When we literally put ourselves in cross-generational shoes, we understand the other’s point of view.

However, when the body swap is cross gender, pitfalls soon reveal themselves. Likewise, as I am finding out, middle grade human-to-pet body swap narratives are also likely to convey problematic gender ideologies.

FREAKY FRIDAY AND ME

When I was ten years old I was a massive writer of fan fiction, though it wasn’t called that then. I rarely finished any story but I was struck by one idea after another. The joy was in the writing, not in the finished product. Sometimes I’d simply write book blurbs with no intention of going any further. One day my teacher found me reading (which was fine — he ran the classroom according to Montessori philosophy), and picked up the little note I’d written to myself. I was using it as a bookmark. The note was mostly written to try out the new green, felt-tipped calligraphy marker I’d gotten for my birthday but I’d written something like: “Write a story about a girl who swaps bodies with her mother.”

“Hmm,” said my teacher, who had read this note despite me wanting to snatch it right back out of his hands. “Have you seen the film Freaky Friday?”

I had not. I told him I had not. This was the late 80s, a long time after the first adaptation (1976) and even longer before the next (1995, 2003). He looked at me suspiciously though, and I felt terrible, as if he had caught me plagiarising someone else’s idea. Perhaps all those times he’d praised my original writing were based on a lie, in his mind.

There’s nothing wrong with letting 10 year olds write fan fiction anyway, imo. Let 10 year olds write whatever they want, even if it’s derivative and unoriginal. The job of a 10-year-old is to revel in the joy of reading and writing.

I think of that shameful interaction each time I come across another body swap story, because they’re so common, no one can really be said to be plagiarising anyone else. The body swap story can be good for conveying all sorts of ‘walk-in-another-person’s-shoes’ didacticism in the most literal of plot lines, so no wonder.

Was Freaky Friday the first major story to do the body swap plot? No — take for example P.G. Wodehouse who wrote a book called Laughing Gas, published 1936. Characters Reggie and Joey inhale laughing gas at a dentist’s office.

Wodehouse may have been inspired by the 1928 story The Master Mind of Mars by Edgar Rice Burroughs featuring the plot line of brain transplants. At that point in history researchers were experimenting with organ transplantation — and had been doing so, both on animals and humans, in the 18th century. (The first successful transplants didn’t happen until the 1950s.)

Although Freaky Friday was not the first popular story to introduce this plot line but is almost certainly the best known to modern culture because of the film adaptations. The original novel was by Mary Rodgers, published 1972. Rodgers also wrote Freaky Monday and Summer Switch. Due to the success of Rodgers’ first body swap novel, at TV Tropes the body swap plot line is known as the “Freaky Friday Flip”.

A number of the hugely popular series writers for children have utilised the Freaky Friday flip at some point:

- The Barking Ghost, Switched and Why I’m Afraid Of Bees by R.L. Stine

- Captain Underpants and the Big, Bad Battle of the Bionic Booger Boy Parts 1 and 2 by Dav Pilkey

- Airhead by Meg Cabot, of Princess Diaries fame

- Freaked Out, a Lizzie McGuire story by Alice Alfonsi

- etc

Features Of The Freaky Friday Flip

From TV Tropes:

- Typically, the main character achieves a deeper appreciation for the other person’s life.

- The Flip often involves characters of different ages, genders, races, or social classes.

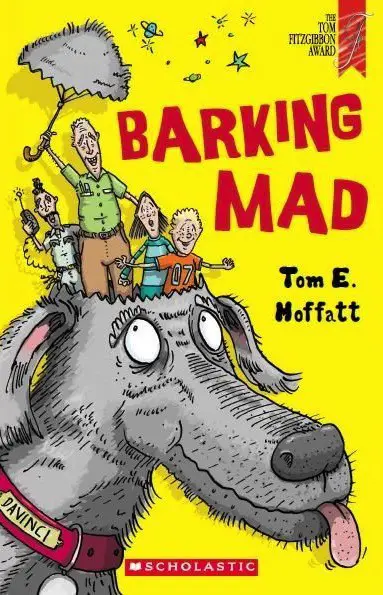

- Another variation is a protagonist and antagonist switching, which usually involves each trying to undermine the other’s organisation while simultaneously trying to switch back. (See Barking Mad, below.)

- The switch may lead to a Heel–Face Turn. That’s when the villain turns good. An inverse Breaking Bad character arc.

- If one or both of the characters have superpowers or other special abilities, they’ll have a lot of trouble figuring their new powers out.

- In the more traditional applications of the trope, the reason for the switch is never explained in-universe. However, the Doylist (real-life, not ‘in-universe’) reason for any application is often to force the age-old moral: To better understand others, you must experience life in their shoes.

Below I take a look at some recent body swap stories, specifically how they excel versus some more problematic tropes.

Barking Mad by Tom E. Moffatt (2015)

In 1997 Scholastic published a few body swap stories for middle grade readers by Todd Strasser and one of those is called Help! I’m Trapped In My Sister’s Body!

Barking Mad is a New Zealand publication by Tom Moffatt, and winner of The Tom Fitzgibbon Award. This story is a body swap story, human swapping with dog.

I never read Strasser’s book in the 1990s but a Goodreads review confirms that I’m right to expect a fraught relationship between brother and sister. I am able to extrapolate the moral lesson as well, because it’s standard in body-swap stories for our main character to ‘find someone’s strengths and use them for good’:

Everything is going well for Jake and his pen pal, until he realizes she is coming to visit. Now he must switch bodies with his big sister, Jessica, who does not like him at all, so that he can cover up a lie that he told his pen pal. Learn what the lie is, how they covered it up, and how the siblings worked together, ending with them actually getting along. This book is a great way to encourage teamwork and finding people’s strengths and using them for good.

Goodreads review

Presumably the main character of Strasser’s story continues to do good even after being returned to his own body.

Barking Mad features a bitchy, annoying, girly-swot teenage girl whose younger brother narrates the story of their body swap from his own close third-person point of view. The book begins in a very appealing way, with ‘mad professor’ granddad gone ‘barking mad’ after inventing a body swap device and accidentally inhabiting his dog’s body. The brother and sister find the machine, accidentally swap themselves, and now we have a Gender Bender story which actually kind of replaces the animal story I thought I was buying for my dog-loving middle-grade daughter.

Come Back Gizmo by Paul Jennings (1996)

Barking Mad is basically a 2015 retelling of a hi-lo short novel by Paul Jennings, written almost 20 years earlier.

Come Back Gizmo is one long humiliation gag. And for true humiliation, a (cishet) boy needs a female romantic opponent. The (literal) girl next door is a highly unsympathetic archetype. Jennings uses this exact description in any story with a sexually attractive girl. She is always a white girl and she always looks like this:

Oh, just look at her. Golden hair. Blue eyes. White, white teeth.

Jennings describes Samantha’s cat, though he is also describing Samantha herself, because he has demonstrated in other stories that girls are in one of two categories: classy and cheap:

Samantha is carrying her cat, Doddles. It’s one of those expensive ones with green eyes. It is a classy cat. There is nothing cheap about it.

The reader is given no reason to like this girl, and we don’t know why the boy likes her either. The truth is, he doesn’t like her at all. He is annoyingly drawn towards her because… hormones. And because boys are not encouraged (in fiction as in real life) to see pretty girls as people.

The situation of a boy hopelessly attracted to a girl he wouldn’t otherwise like as a friend draws upon a universal feeling of youthful attraction… perhaps. This might explain the popularity of the trope, in which a boy keeps making a buffoon of himself, especially in front of the girl he likes. (In a warped version of gender equality, there are stories now where girls are also the buffoons in front of hot boys.)

But there’s another side to this trope, as used in this story, which presents another ‘universal truth’: That women (and girls) are manipulative liars.

- Jimmy assumes (as a universal truth) that Samantha would be interested in him because he ‘doesn’t have a dollar to his name’. The universal truth as presented: Girls like boys who have money. Girls are gold-diggers.

- Samantha forges a bargain with Jimmy in exchange for a kiss. The implies a universal ‘truth’ that girls fully understand their own sexual appeal, and will manipulate hapless boys into doing exactly what they want. A secondary universal ‘truth’ is that girls are the natural gatekeepers of sex.

- Later, Samantha lies to the ‘little man’ from the SPCA when she insists she had nothing to do with locking the dog in the boot. Implied universal truth: That girls are liars. We might code this as ‘Samantha, this particular character, is a liar’, except this plot point follows on the back of Samantha as sexually manipulative, and the attributes go hand-in-hand. Also, the trope of the manipulative, self-centred, beautiful, sexually alluring and wholly unlikeable girl is a trope we see time and again throughout history.

The most disappointing aspect of Paul Jennings’ body swap dog story: It didn’t even need the romantic subplot bookending each end. The girl exists in the story purely to heighten the humiliation aspect of Jimmy running around naked, scratching fleas, cocking a leg on lampposts.

In response to this argument I’ve heard ‘both sides’ rebuttals: Sure, the girl is a manipulative liar, but the boy really is made to look stupid in this. Surely that’s not sexist now? I mean, the girl AND the boy are presented in a bad light. In fact, if anything, it’s reverse sexism!

That’s how the argument goes. But it doesn’t hold water, because

- If you flipped the genders the gag in this story wouldn’t work (ie. it would just be weird and uncomfortable, seeing a girl run around naked in front of the entire neighbourhood)

- For this exact reason: we objectify the bodies of girls

- Therefore a girl’s naked body cannot be funny; her body is always viewed through a sexual lens. Only boys have the privilege of running around naked without being viewed via a sexual gaze.

And I suppose this is why we don’t get many body swap stories in which girls swap bodies with their dogs. Girls sometimes get werewolf stories instead, which is etymologically interesting: ‘Were’ means ‘man’. The female ‘werewolf’ is a very recent development in storytelling. The etymologically correct term for a female werewolf would be wifwolf, but that means ‘wife wolf’. It’s not exactly liberating to be described only in relation to a man, especially since the entire genre of werewolf stories are about ‘breaking free of constraints’, which explains why werewolf is now coded as a gender free term.

Quantum Leap

Quantum Leap was a 1980s American TV show. In each episode, main character Sam Beckett finds himself in someone else’s body. He is there to solve a crisis in their lives. This is a surprisingly earnest show, and oftentimes Sam dresses as a woman without playing it for laughs. Despite regular lighthearted moments, nothing about the tone of an episode suggests we should laugh at Sam when he dresses his masculine actor’s body in a woman’s one-piece bathing costume, for instance.

Despite the earnestness, Quantum Leap again exemplifies why it is nigh on impossible to write a gender-swap body swap story without relying on sexist stereotypes. In the clip below, the male chauvinist boss who comes onto his much younger secretary gets his comeuppance. On the surface, this is a send up of what we now call toxic masculinity.

But when proving to this guy that he’s ‘really’ a man, Sam ‘proves’ it by offering to demonstrate how he can throw a baseball. This doesn’t work as ‘proof’ unless the audience believes girls can’t throw baseballs.

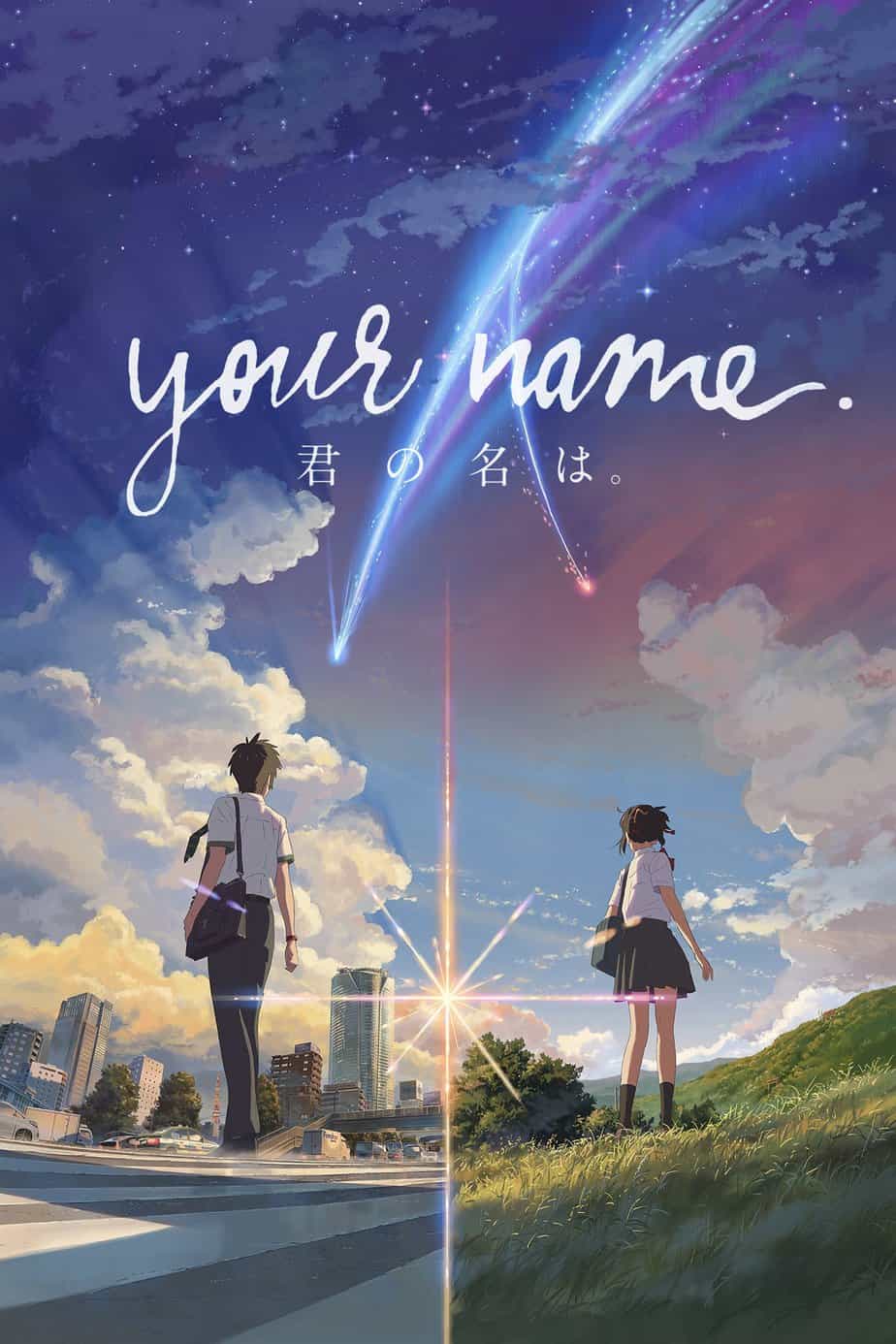

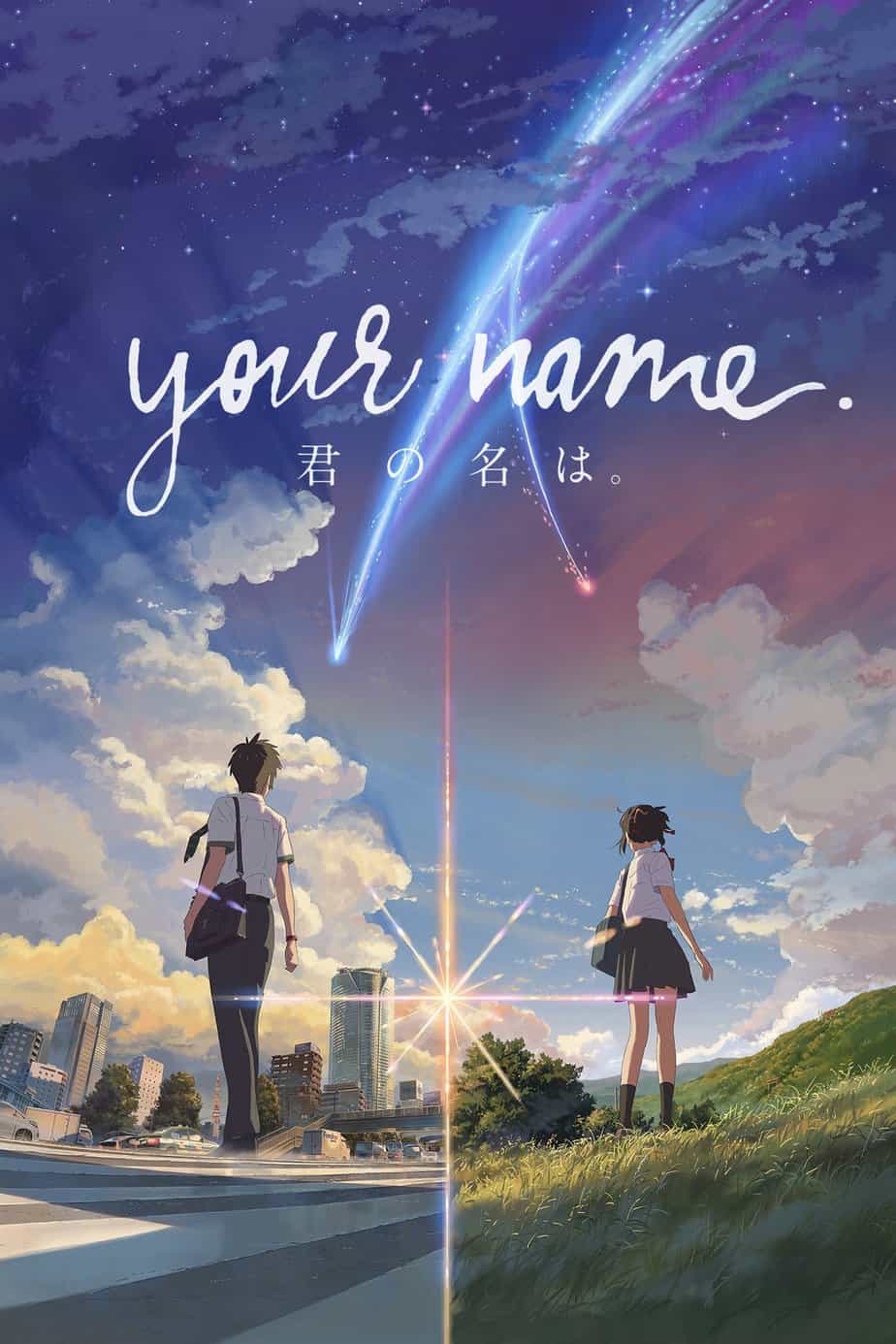

Your Name (2016)

Gender Stereotyping

Your Name avoids much of the ickiness of a brother-sister body swap that we saw in Barking Mad. (Insofar as the characters know) they don’t know each other. Writers nevertheless rely on some stereotyped ideas about how boys and girls are different:

- When transplanted into the girl’s body, the teenage boy develops a bit of an obsession with feeling her boobs. (Stereotype: Boys are obsessed with sex and will take any opportunity to be sexual with a girl.)

- When transplanted into the boy’s body, the teenage girl is absolutely terrified at the thought of dealing with someone’s penis. (Stereotype: Girls are terrified of the penis/sex with boys. At least, sympathetic girls are. Bad girls are driven by it.)

I occasionally agree with Germaine Greer, and I agree when she writes:

The truth is … that female fearfulness [of the penis] is a cultural construct, instituted and maintained by both men and women in the interests of the dominant, male group. The myth of female victimhood is emphasized in order to keep women under control, so that they plan their activities, remain in view, tell where they are going, how they are getting there, when they will be home. The myth of female victimhood keeps women ‘off the streets’ and at home, in the place of most danger.

The atmosphere of threat that women feel surrounded by is mostly fraudulent. The sight of a man exposing his genitals causes fear; the man who exposes ‘himself’ is almost always rewarded by the sight of submissive behaviour as women passing by avert their eyes and hasten their steps. Submissive behaviour may be what such a man can exact by no other means. In the case of flashing, the proper response would seem to be hilarity and ridicule, to deny the flasher his kick. A middle-aged woman used to enjoy trotting around Cambridgeshire villages naked under an army great-coat. ‘What do you think of that then?’ she would say to surprised shoppers, as she held the coat open. ‘Very nice, dear,’ they would say. In [some] law women are deemed incapable of indecent exposure. A woman’s body signifies nothing; a man’s body, or rather the attachment to a man’s body, signifies power over life and death.

To complain to police is to reinforce the flasher’s belief in his penis’s magical power to amaze and appal. In truth the man standing with his pants down is extremely vulnerable, not least through the thin-skinned genitalia themselves.

The Whole Woman

RACIAL STEREOTYPING

White/Black gender swapping can be equally problematic when covered in the context of a body swap story.

An example of highly problematic racial body swapping in narrative: “Freaky Friday” by Lil Dicky featuring Chris Brown, obviously a spin on the 1970s mother-daughter body swap story.

At first glance it’s easy to dismiss this music video as not rap but a spoof on rap (it’s even in the set-up, with a white guy explaining the work of Lil Dicky to his girlfriend, who has never heard of him). It’s also easy to dismiss this music video as simple self-deprecation comedy. But as Peggy Orenstein says in her book Boys and Sex, as part of a book-length discussion about the pressures American young men are under:

The video plays with how white guys see (and are conditioned to see) black masculinity: as simultaneously aspirational and threatening, what sociologist Michael Kimmel has called a defiant mix of “athletic prowess, aggression, and sexual predation.” But adopting these trappings — through what they listen to or watch, in the posters on their bedroom walls, in who they talk, dress, walk, dance, in whom they idolize — is as likely to reinforce as to challenge stereotypes.

Peggy Orenstein, Boys and Sex (2020), p141

The Anime Advantage

Anime is a particularly good medium for the body swap trope because of the following advantage:

When this plot is done in animation, usually the voices also switch as narrative cheat to help younger viewers keep track of who’s who.

TV Tropes

Though they don’t know each other, Mitsuha and Taki find themselves occasionally trading bodies, a mix-up that seems to have something to do with an approaching comet, though neither can quite figure out what. So they decide to make the most of it, and in the process find they’re improving each others’ lives. Mitsuha, in Taki’s body, is bolder with Miki, even setting up a date that Taki then nervously has to make good on. Taki takes more chances as Mitsuha than Mitsuha would ever take on her own. They leave notes for each other. They develop a rapport. They begin an odd, but oddly functional, relationship in which they never meet but know each other better than anyone else. And then Mitsuha disappears.

It’s here that Your Name transforms from a sweet, sort-of romantic comedy into an X-Files-ish mystery. It’s also at this point that the film becomes a little less compelling. After spending so much time on Mitsuha and Taki’s relationship, Shinkai’s film isn’t quite as assured when they’re on their own. Still, the emotions keep it moving, to say nothing of the visuals. Shinkai lets the drama play out against sumptuous landscapes — be it the hills around Itomori or the streets of Tokyo — unforgettable places he fills with passionate, searching characters haunted by a happiness that eludes them and a loneliness they’re not sure they can ever overcome — even if they suspect they have a soulmate chosen by the stars themselves. By the time Your Name reaches its moving finale, the Next Big Thing tag doesn’t seem quite enough for Shinkai. He’s arrived already.

Beyond The Multiplex

A RELATED STORYTELLING TRICK

Sometimes, there is no supernatural/fantasy body-swapping that takes place but rather a psychological one.

This technique can be seen in the following short stories:

- “Who’s-Dead McCarthy” — the narrator starts to become obsessed with death after lampooning an old man for being obsessed with same.

- “Sucker” by Carson McCullers — a teenage boy is rejected by a girl and in retaliation, rejects his younger cousin. This upends the psychologies of the characters completely.

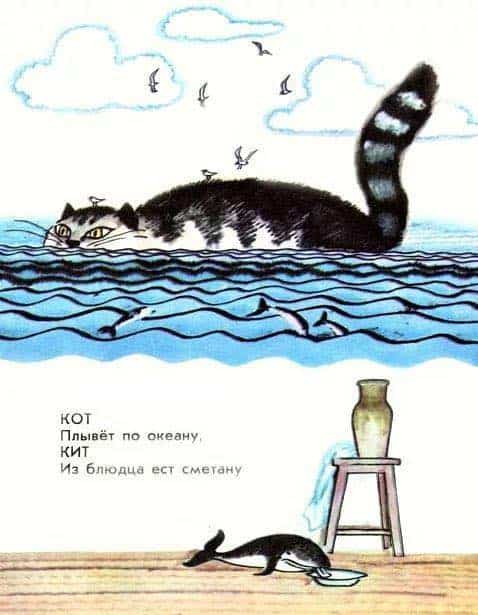

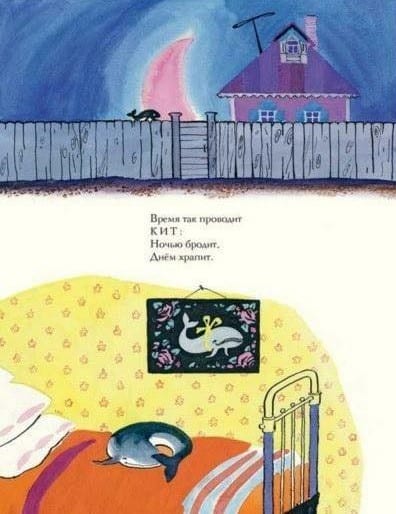

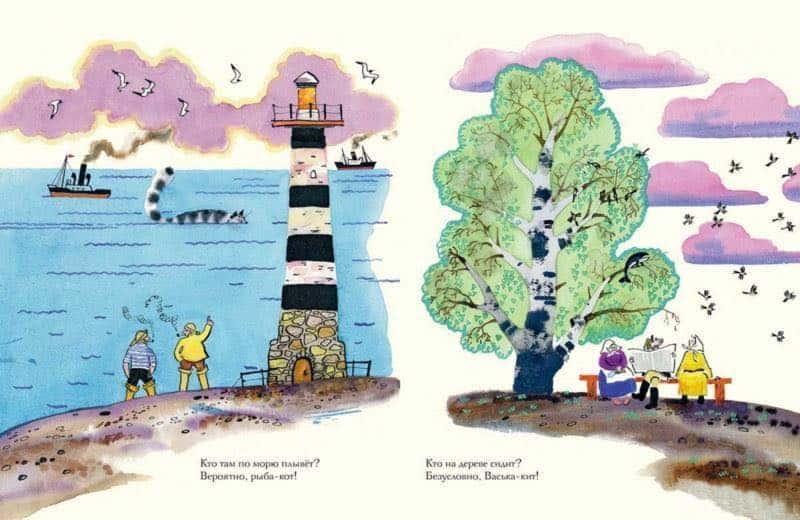

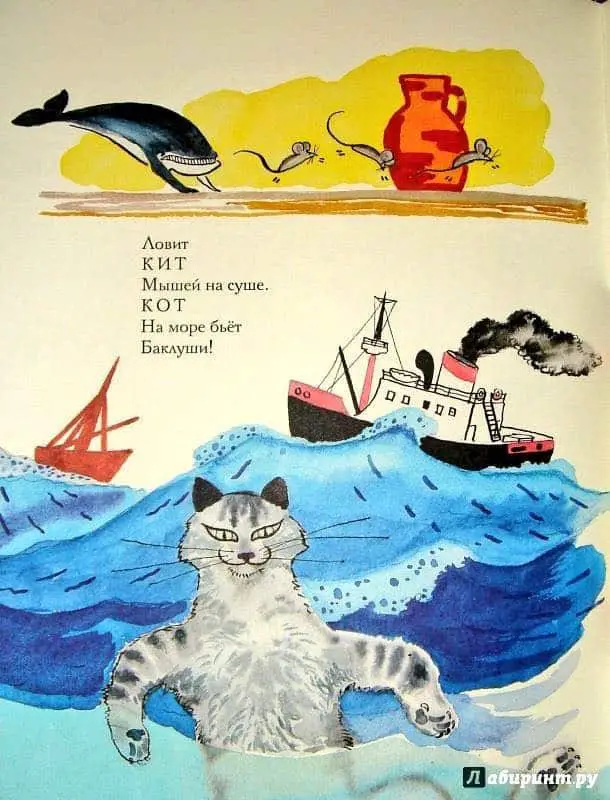

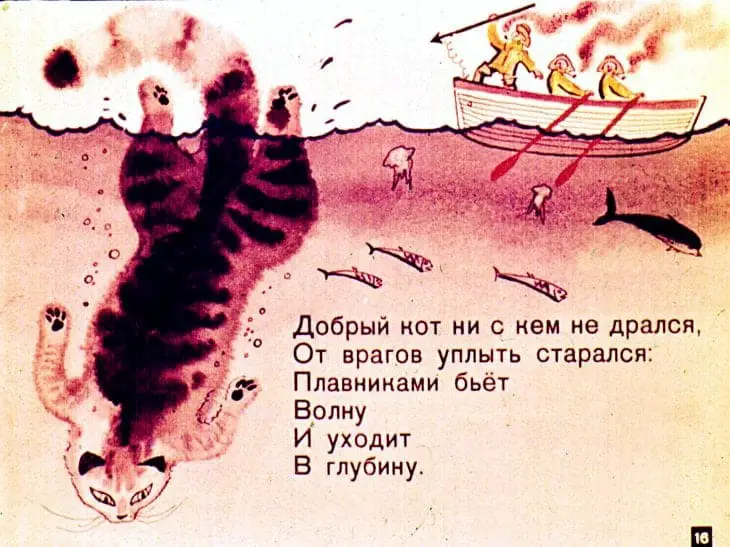

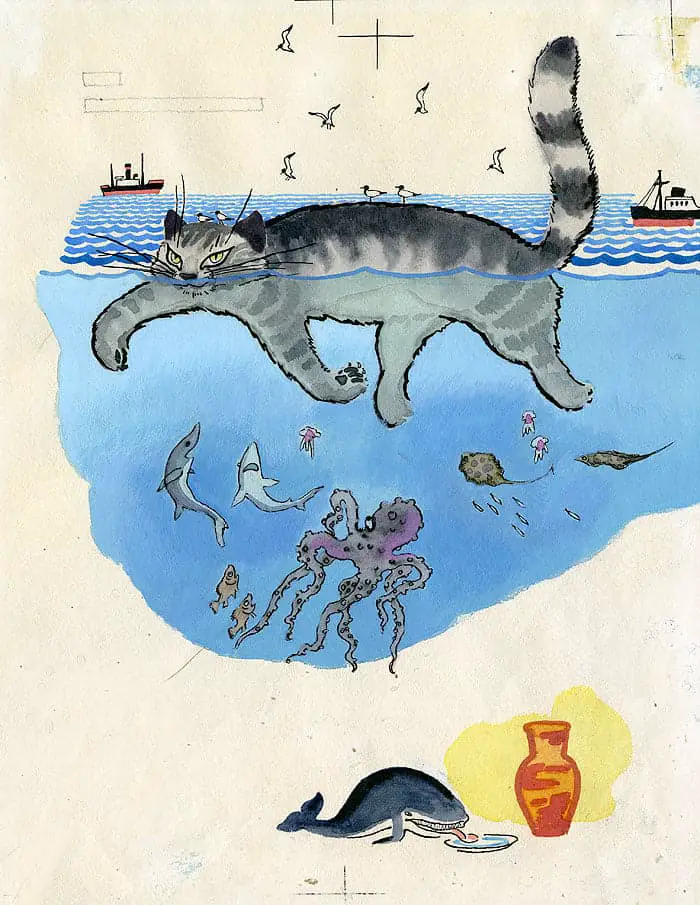

When storytellers steer clear of body swaps which focus on a reversal of (binary) gender, body swap stories can be very funny. Check out these comical illustrations below, in which a cat and a whale swap places. In Russian, the word for whale is “Kit”.

And here is a black and white version to read online.

RELATED TROPES

A similar idea, with less learning and more evil, is Grand Theft Me.

- Personality Swap — the characters’ personalities are swapped but their minds stay where they are meant to be. It will often involve similar tropes to transformation stories (such as Gender Bender) as this is essentially two of these in one, with the addition of confusion resulting from the transformations being into other known characters.

- Body Swap Stories, a Wikipedia list

- Freaky Friday Body Switching Stories, a Goodreads list

SEE ALSO

Gender Inversion as Gags in Children’s Literature

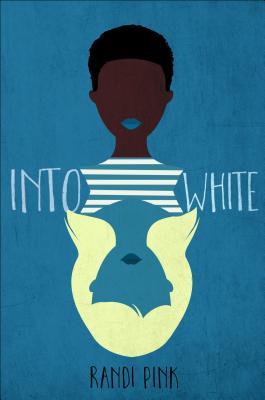

When a black teenager prays to be white and her wish comes true, her journey of self-discovery takes shocking–and often hilarious–twists and turns in this debut that people are sure to talk about.

LaToya Williams lives in Birmingham, Alabama, and attends a mostly white high school. She’s so low on the social ladder that even the other black kids disrespect her. Only her older brother, Alex, believes in her. At least, until a higher power answers her only prayer–to be “anything but black.” And voila! She wakes up with blond hair, blue eyes, and lily white skin. And then the real fun begins . . .

Randi Pink’s debut dares to explore provocative territory. One thing’s for sure–people will talk about this book.