Australia has a uniquely trusting relationship with its police force. We might say the image of police here in Australia is based on a storybook image, one which is cultivated in white kids from the time we start reading children’s books.

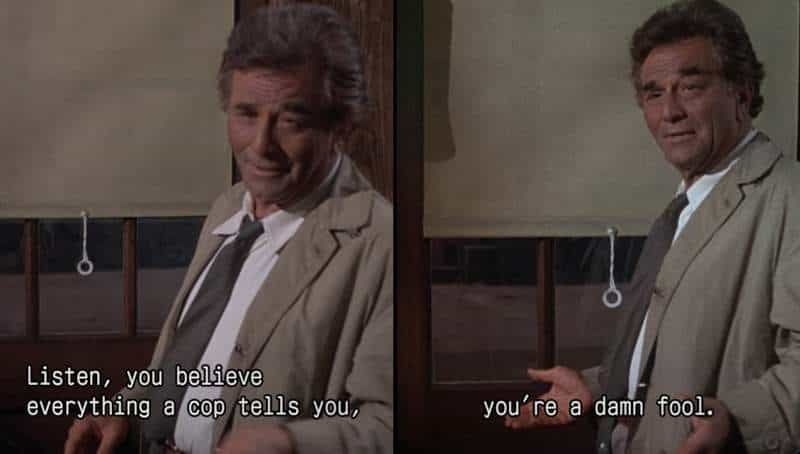

The only feelings mankind has inspired in policemen are indifference and scorn.

UN FLIC (Jean-Pierre Melville, 1972)

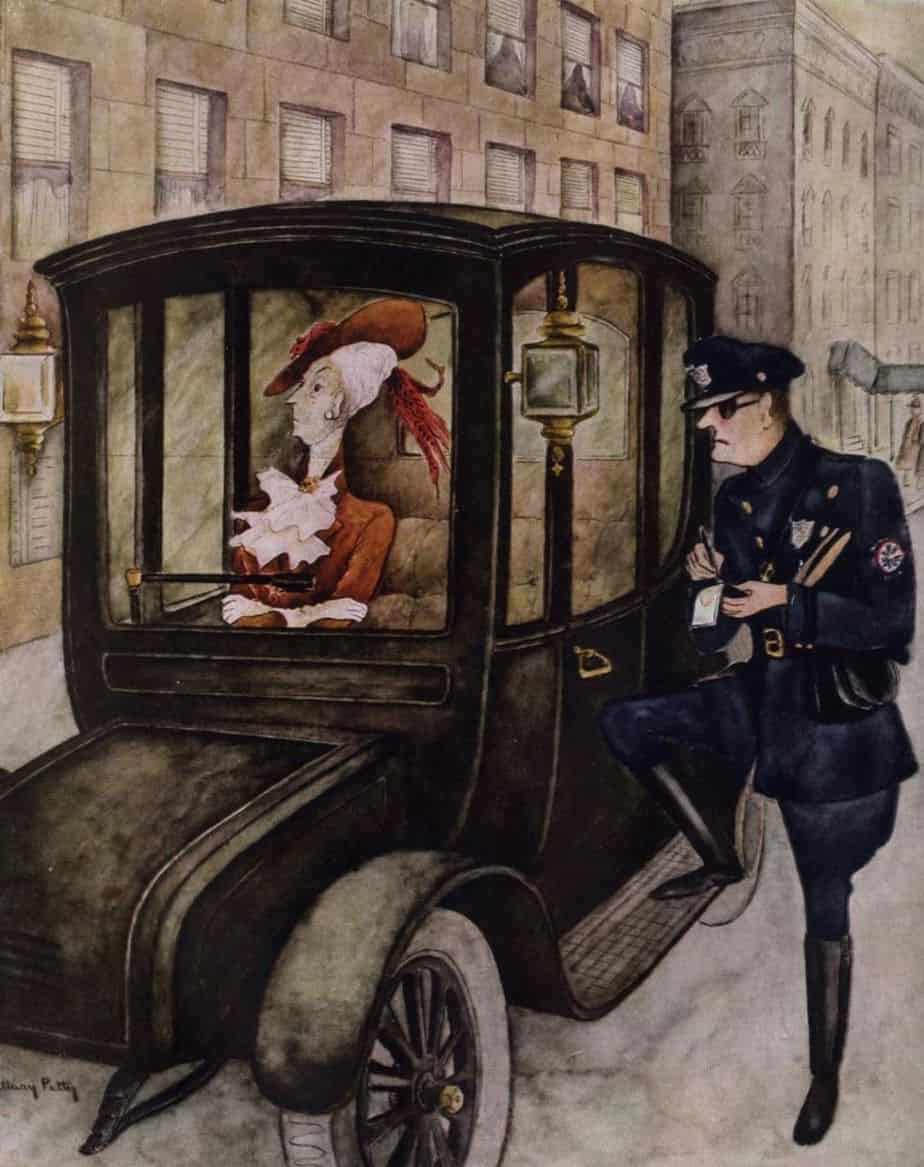

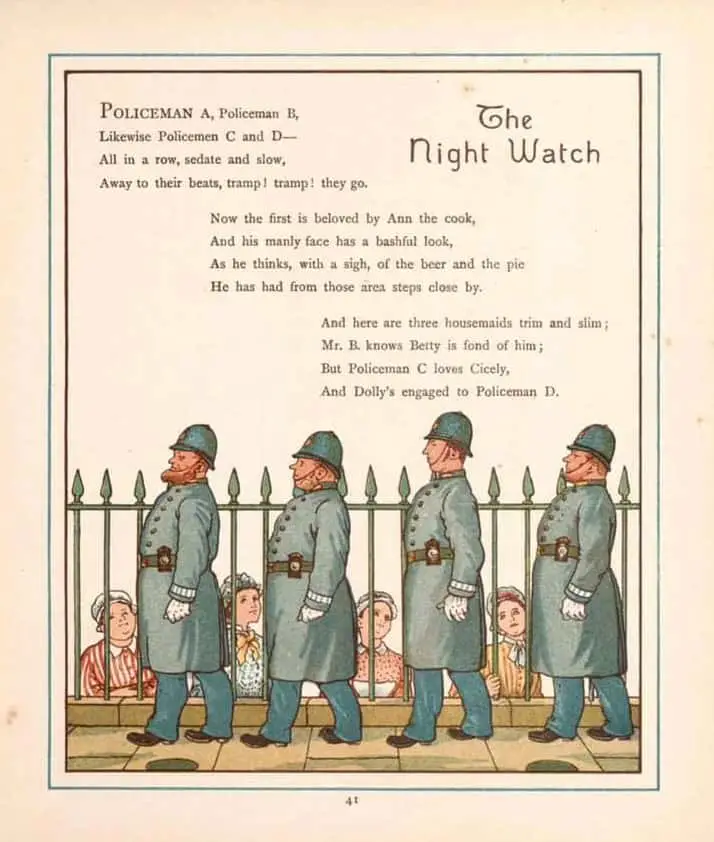

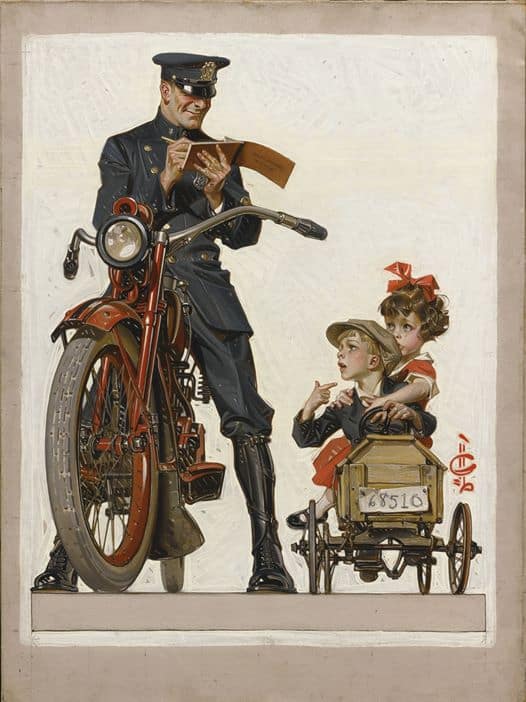

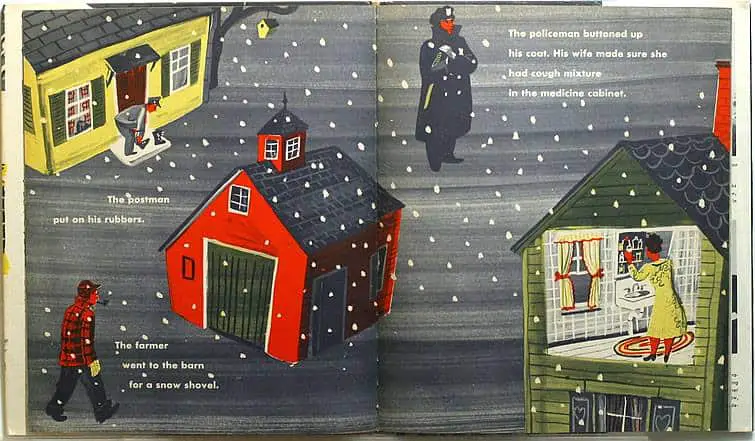

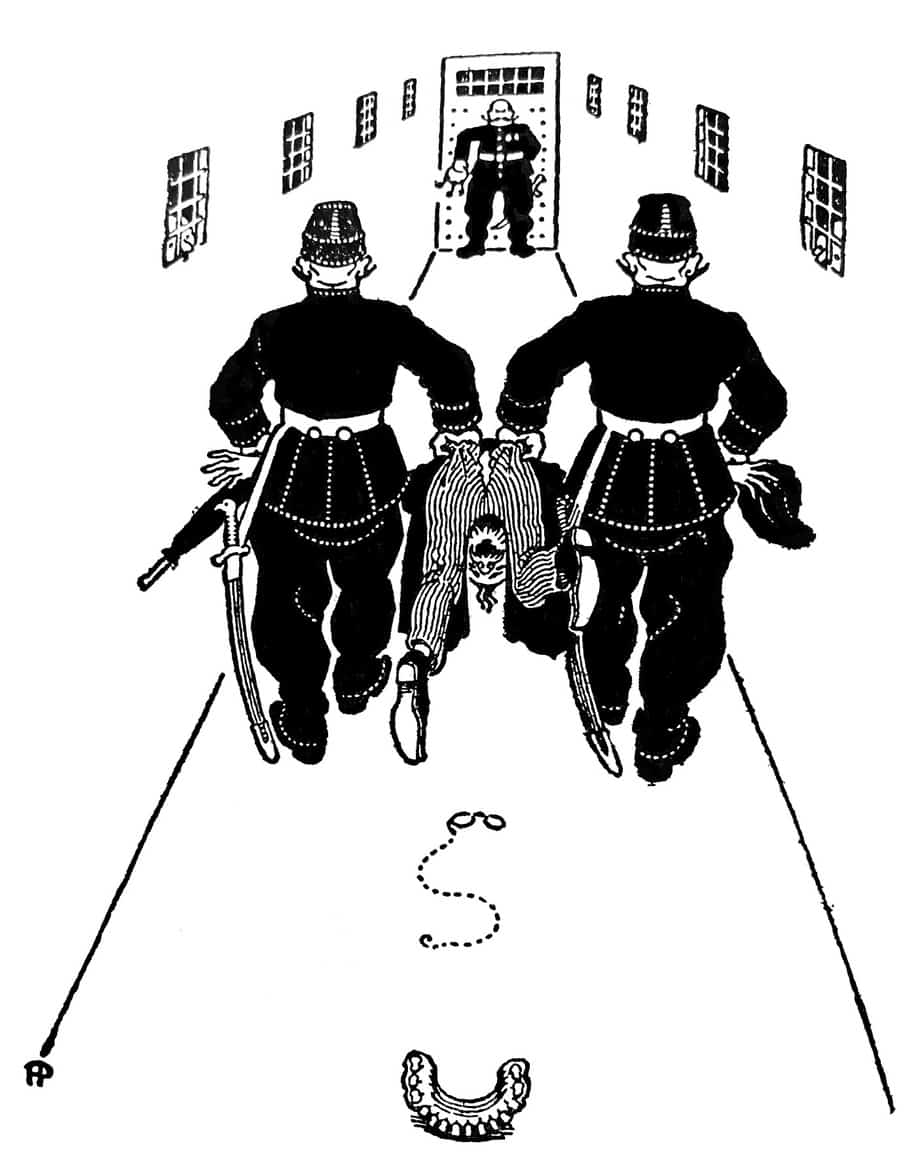

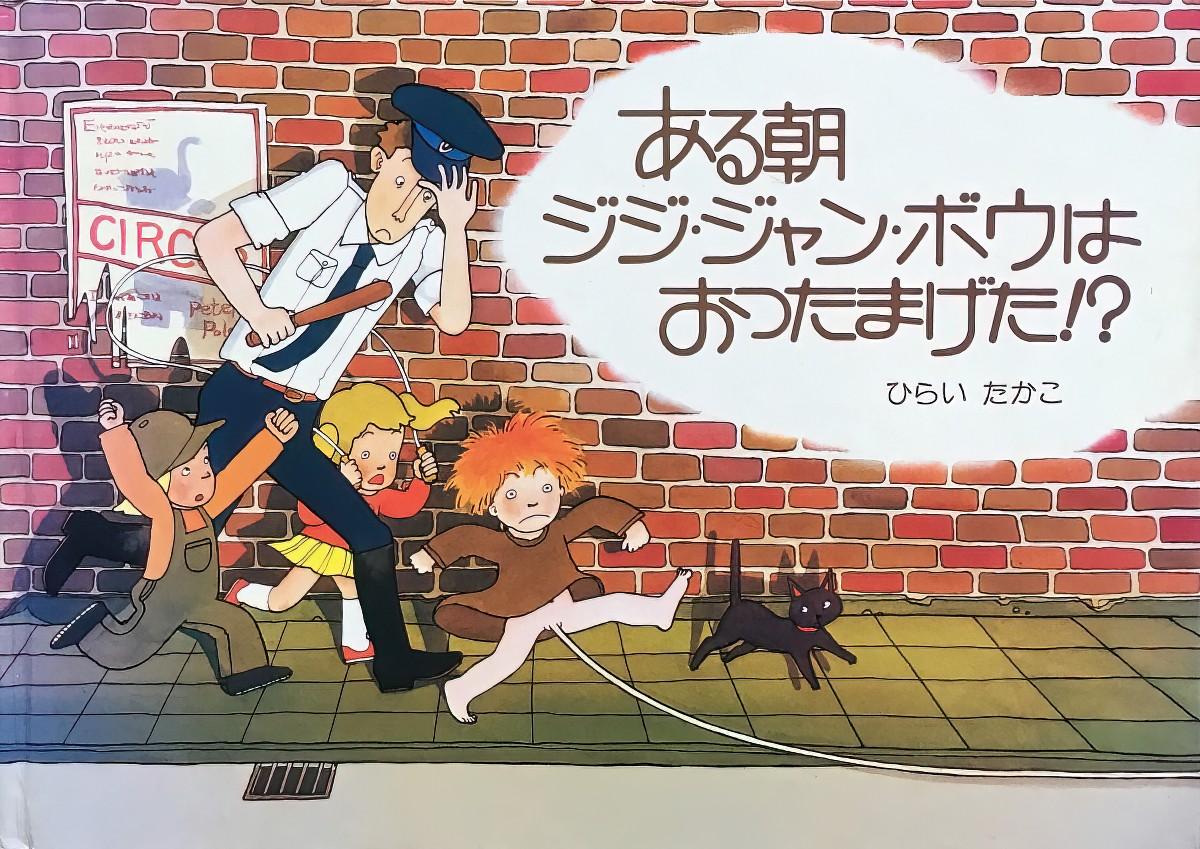

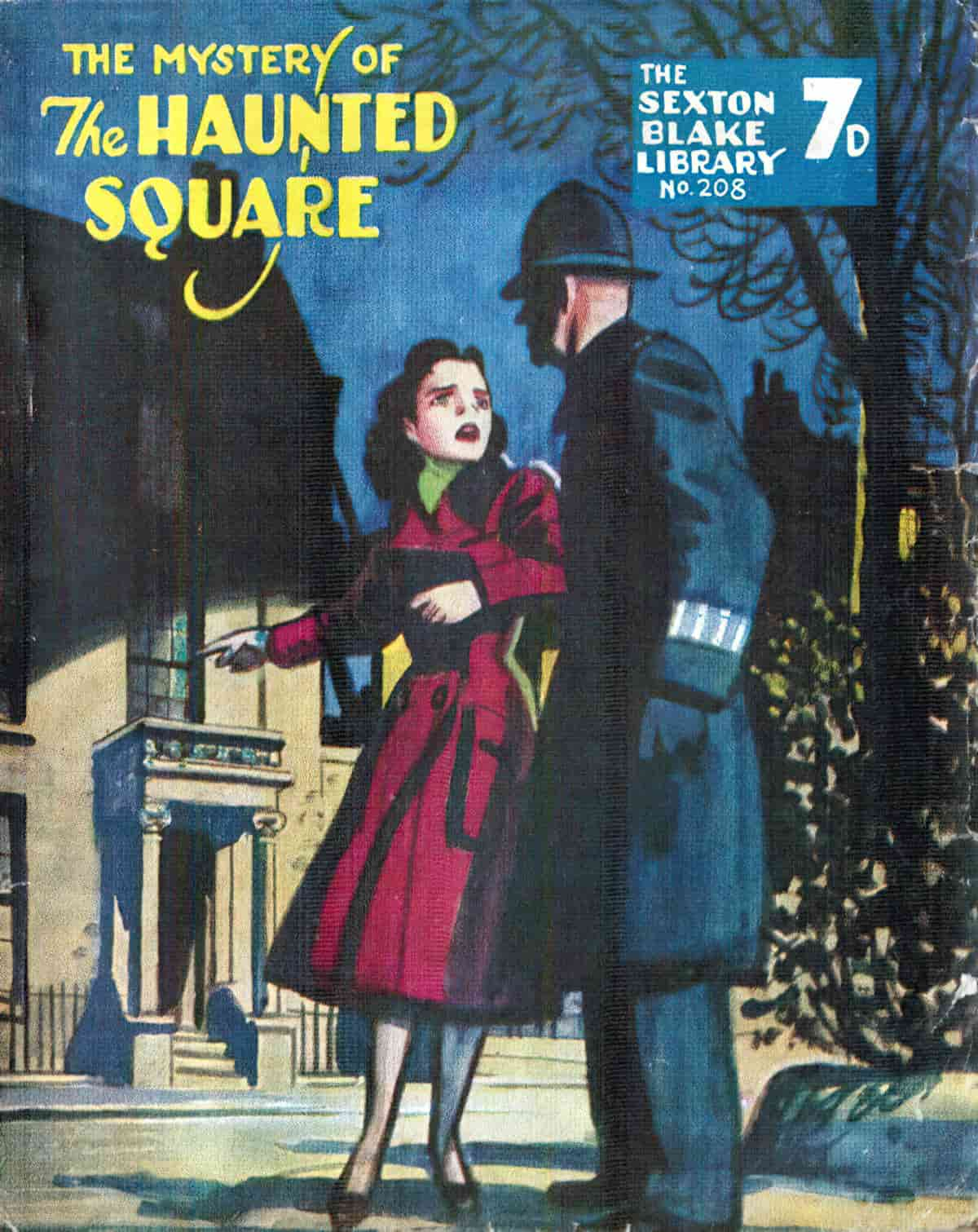

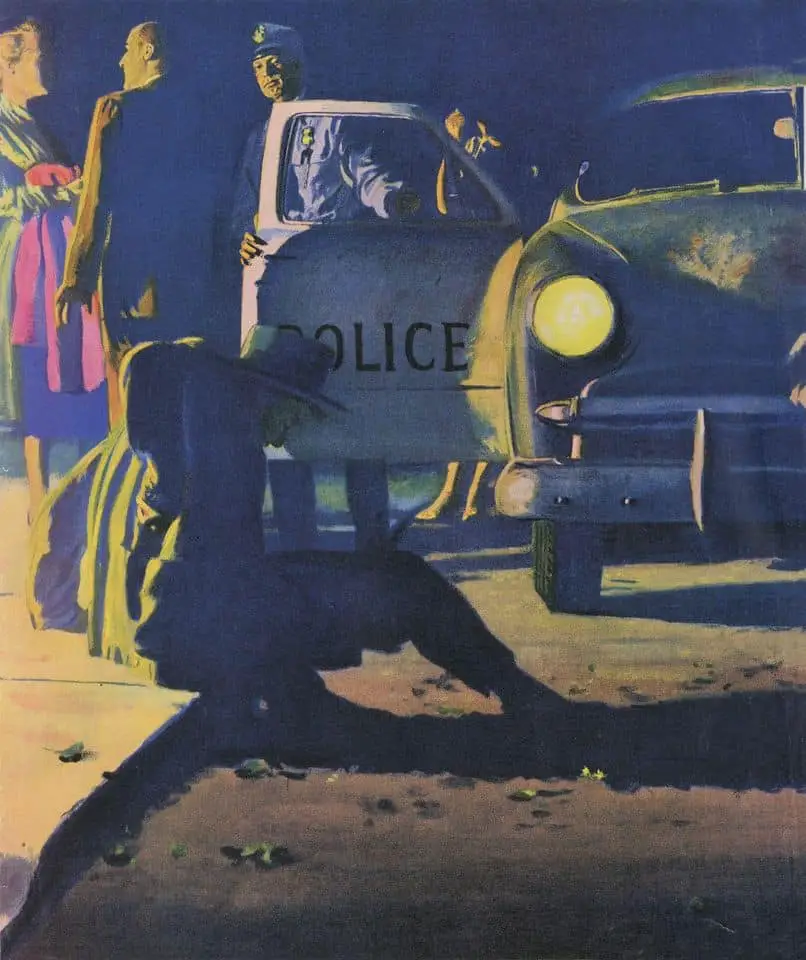

Today I’ll look at some of the main ways writers and gatekeepers protect the image of the police officer as a patriarchal protector above reproach. This archetype is common in utopian stories for very young children and was especially prevalent in earlier Golden Ages of children’s literature.

The Storybook Policeman is just that — he is a man. Female officers are rarely seen in children’s stories. The trend towards avoiding police officers as saviours coincided with the reality of more female officers, which probably accounts for that. The number of female police officers in Australia has doubled over the last 20 years, but in America remains where Australia, New Zealand and England were back in the 1990s.

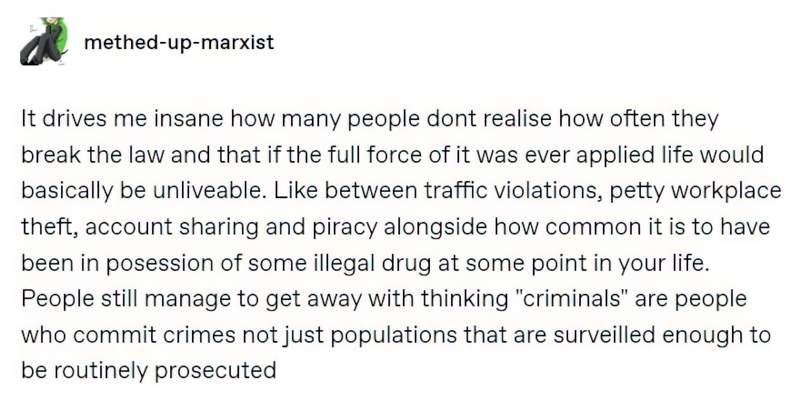

We can say “hire decent human beings as police officers” hoping to reduce police brutality, or “Hire decent people for executive roles in business” hoping to reduce brutality at work. The problem is that police recruits & junior execs may walk into the job as decent as anyone. We have to address the system, which is designed in both cases to turn regular people into machines that can’t see other people’s humanity. That’s why the conventional cop-out “My boss is just a jerk, that’s all – a horrible human being” has never helped anyone. The system turned a regular person into a cruel boss, something it does a thousand times a day, in stages. We have to see the systemic nature of both problems (brutality perpetrated on the public by law enforcement and on employees by employers) in order to solve them. Evil bosses are sad, fearful, powerless people. The only power they feel is the power conferred on them by the organization – that is, by the system. Folks are always shocked to meet people who know their evil boss socially and swear the boss is a great person outside of work.

Liz Ryan, CEO, Human Workplace (@humanworkplace) May 26, 2020

The real-world percentage of female officers is irrelevant to the Storybook Image, just as it was irrelevant in America in the wake of September 11, 2001. Susan Faludi writes about this extensively in her book The Terror Dream, but media outlets exclusively chose images of men saving women, even though a significant proportion of the first responders that day were women.

I don’t think there was any task that was performed down there by men that were not performed by women.

Terri Tobin, Deputy Inspector of the New York Police Department

Another significant proportion of the public does not want to see women saving men, and won’t believe it even if they do see it. Faludi talks about ‘the myth of cowboy bluster and feminine frailty’, which must exist as a duo in order to make sense.

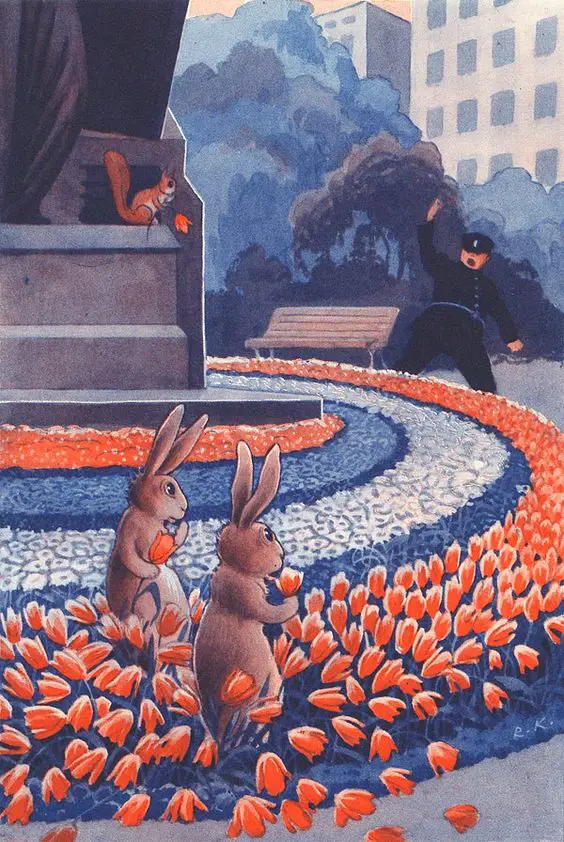

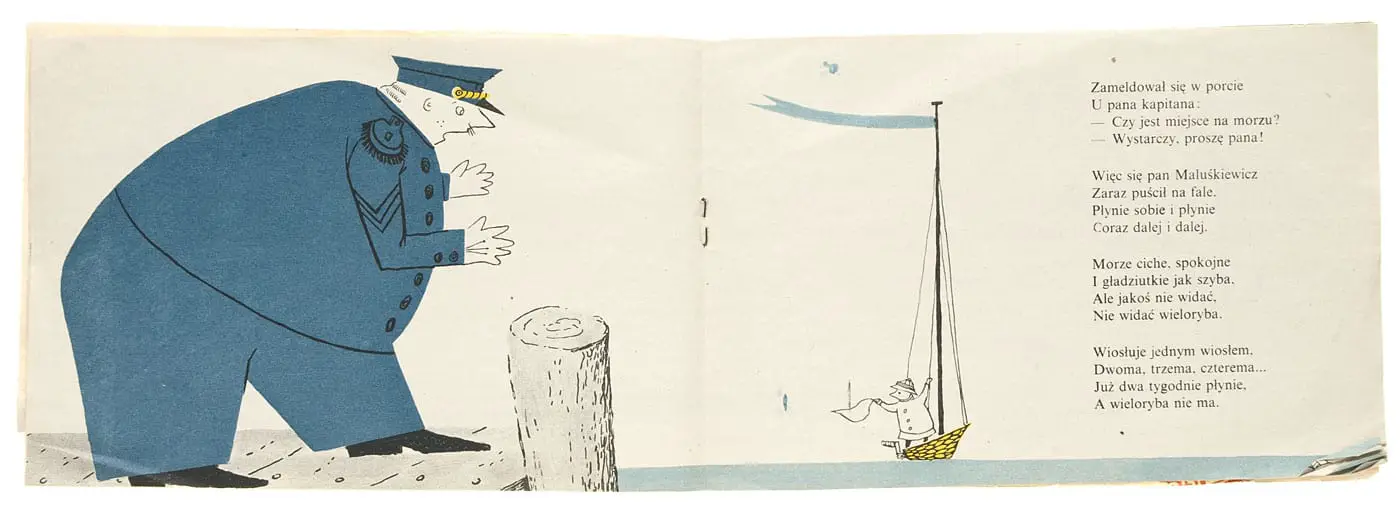

Not surprisingly, we see this dynamic play out in children’s books from earlier ages of children’s literature, in which children seek the help of kindly and trustworthy police men in times of need. These men stand omnisciently over proceedings and the children are free to roam, knowing that a strong man, the huntsman in Red Riding Hood’s woods, is only a scream away.

When we base our security on a mythical male strength that can only increase itself against a mythical female weakness — we should know that we are exhibiting the symptoms of a lethal, albeit curable, cultural affliction

Susan Faludi, The Terror Dream

In books for children, the policeman is never far away. Roald Dahl deals with this fact knowingly in Danny The Champion Of The World, while at the same time fully utilising the trope:

At this point, pedalling grandly towards us on his bicycle, came the arm of the law in the shape of Sergeant Enoch Samways, resplendent in his blue uniform and his shiny silver buttons. It was always a mystery to me how Sergeant Samways could sniff out trouble wherever it was.

Roald Dahl, Danny The Champion Of The World

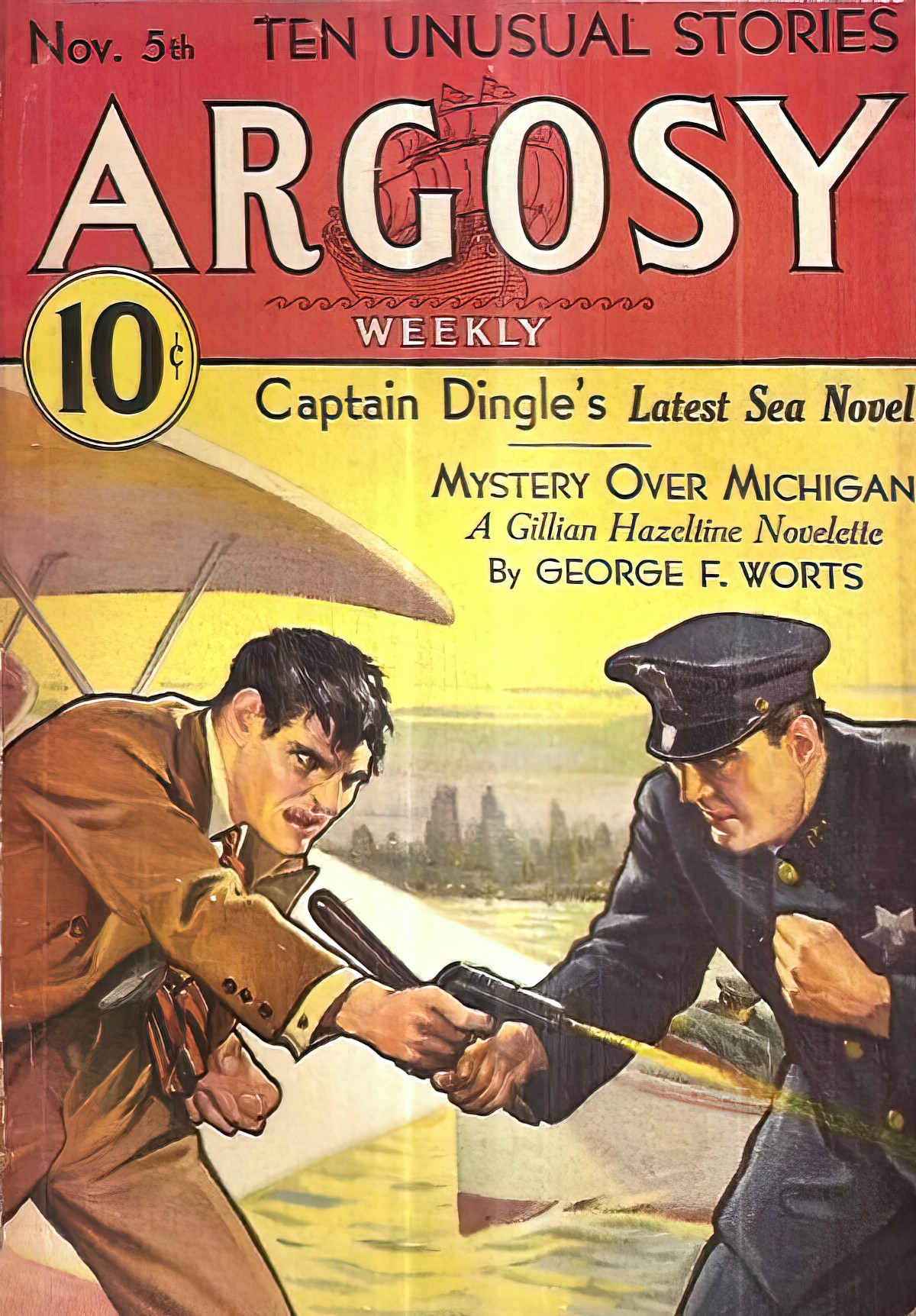

The police car always at the ready is not limited to literature for the youngest audience. It’s a trope we see across all forms of storytelling. There are many police related tropes, and you can find them beautifully catalogued over at TV Tropes. In adult story we more often see the inversion — the useless or very human cop. Yet elements of the effective police force are there nonetheless — the willingness for cops to put rape tests forward for testing, the rapidity at which paperwork gets processed, calls returned. Though evil is rife in fictional adult policing, sheer ineptitude is vanishingly rare. Audiences do not enjoy watching ineptitude. We like our heroes and our villains to be agentic, to be motivated, to have a plan. We like to see them carry plans out.

It’s often said that the best cops would make the best criminals — by chance they’re working on the right side of the law. Crime drama makes the most of this. In The Wire, Jimmy McNulty is a good cop because he has an intuitive understanding of what motivates the criminals he’s working with. The audience sees Jimmy himself go against the rules and resisting the hierarchy that exists within the police force.

The Storybook Policeman is also white. This trope is yet another way in which picture books serve white people and their children. A Black parent cannot afford to teach their children that police are the benevolent patriarchs to call in any emergency.

I’m reminded of the episode of British TV cartoon Peppa Pig about spiders. The message: Don’t be scared of spiders. Spiders won’t hurt you. This reassurance served its purpose for children who wouldn’t leave Britain, but did not serve Australian kids at all. Australian kids need to be scared of spiders. The episode was not aired on Australian television. Likewise, the Storybook Police Archetype only works for some kids and remains actively detrimental to others.

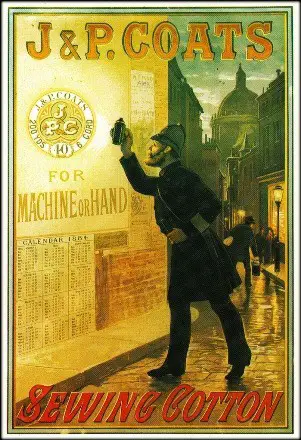

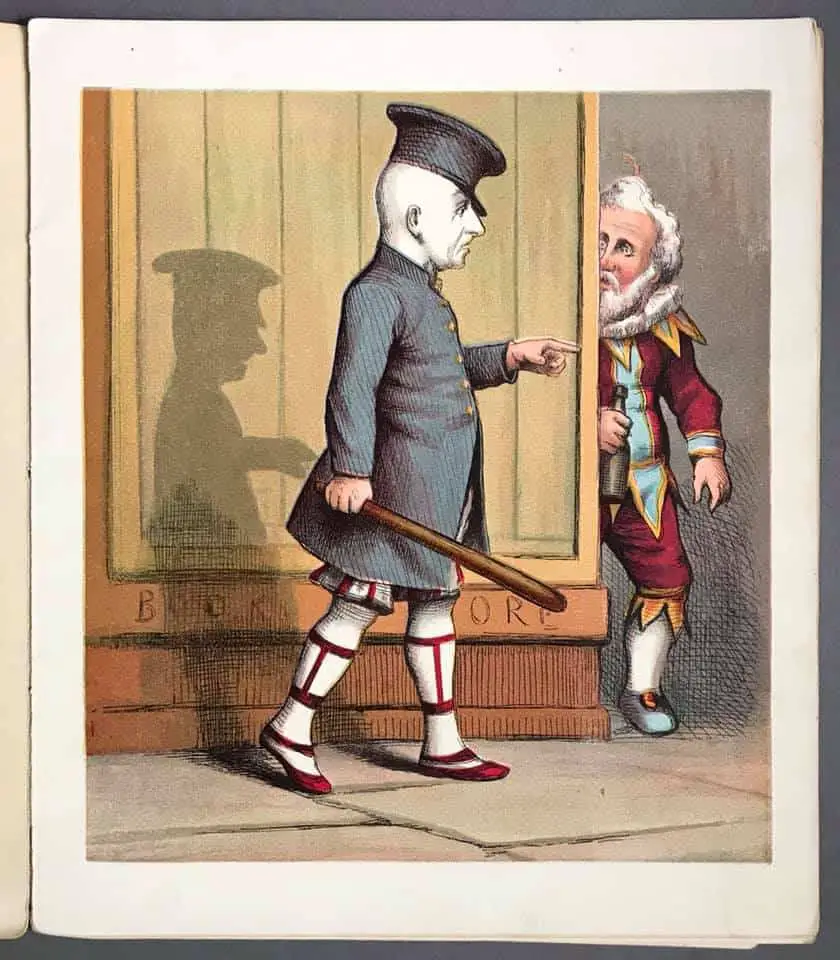

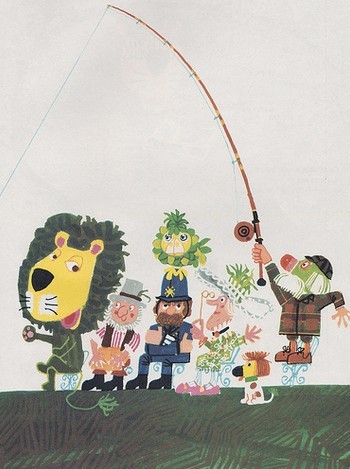

When the Storybook Police is made into an animal, we see the identifying features: The hat and the baton.

White parents have been heavily invested in protecting the image of the Storybook Police Archetype. At times, in America, it has reached ridiculous levels. Sylvester and the Magic Pebble by William Stieg depicts police as pigs. For this reason the picture book has been banned intermittently.

How Do Contemporary Authors Deal With Police?

Apart from the very real political issues, there are some storytelling pitfalls to avoid when storytellers bring police into a children’s story which, by definition, should be about kids, with the action driven by kids, and problems solved by kids.

“Why don’t they just call the police?” That’s exactly what a children’s writer does not want the reader to think. Police therefore create a problem for writers similar to the problem of parents and caring adults in general: Why don’t these children tell a parent?

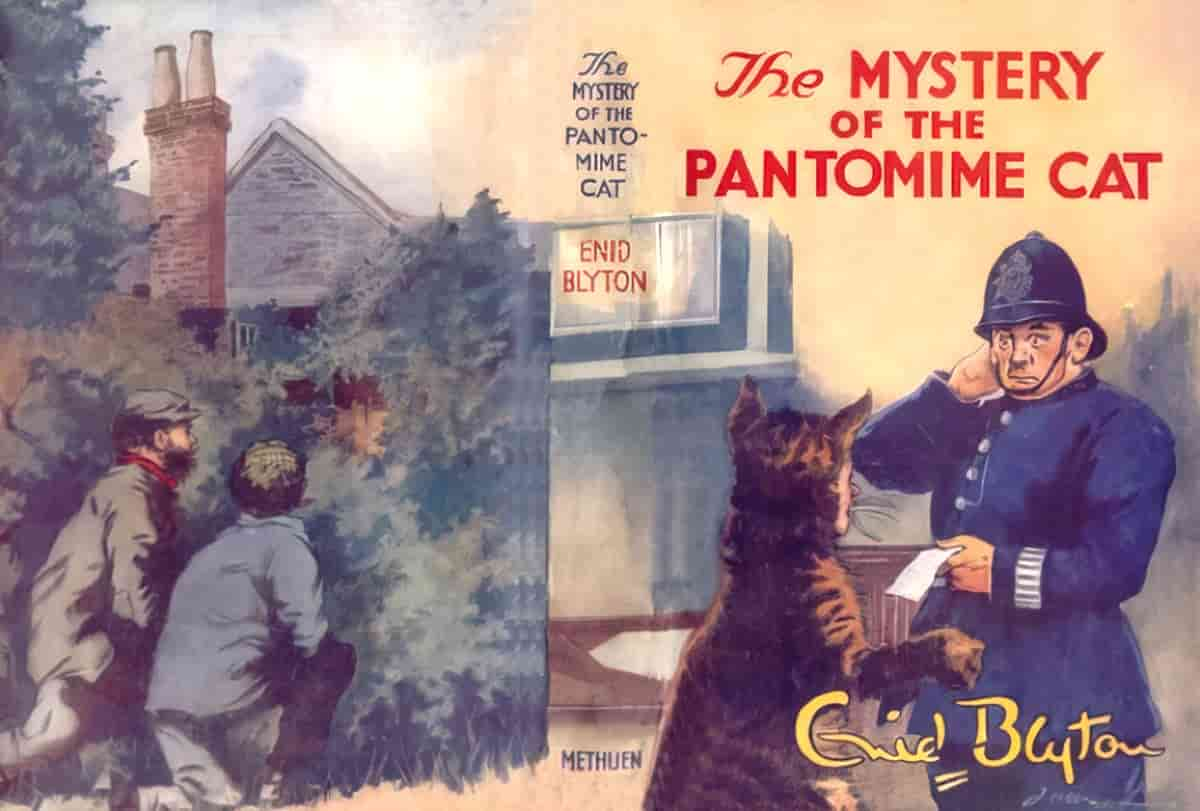

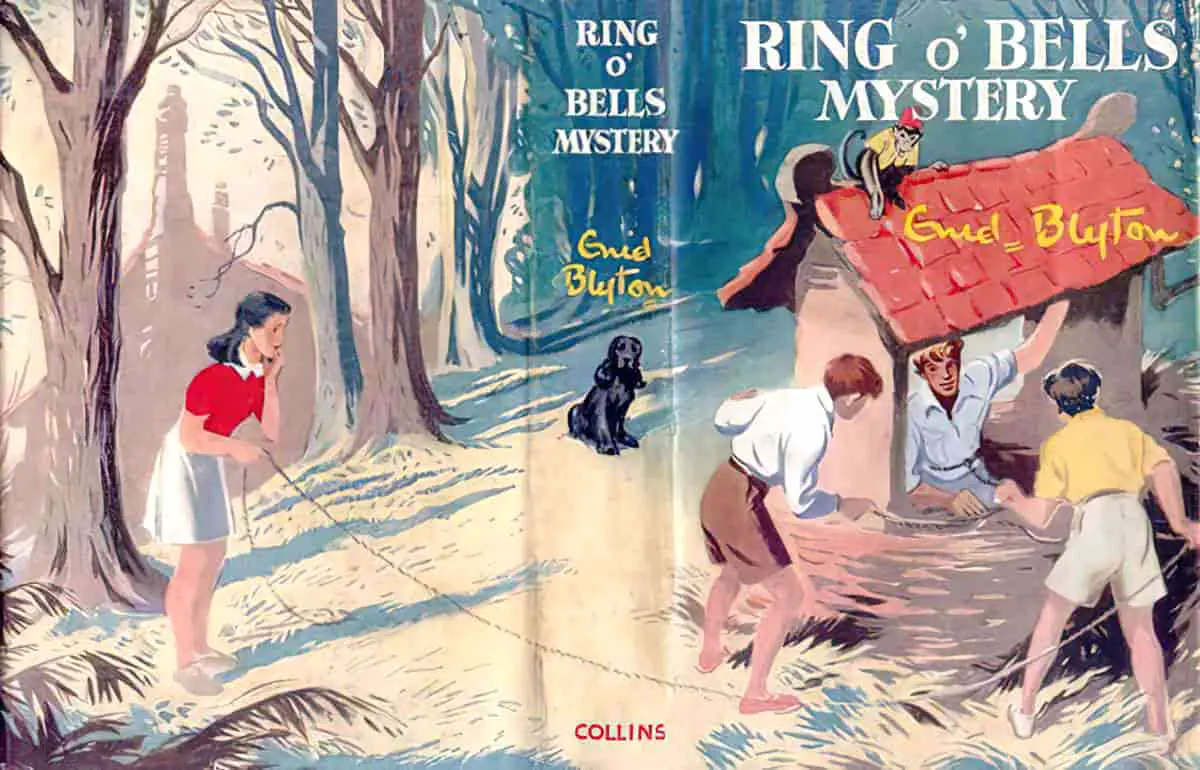

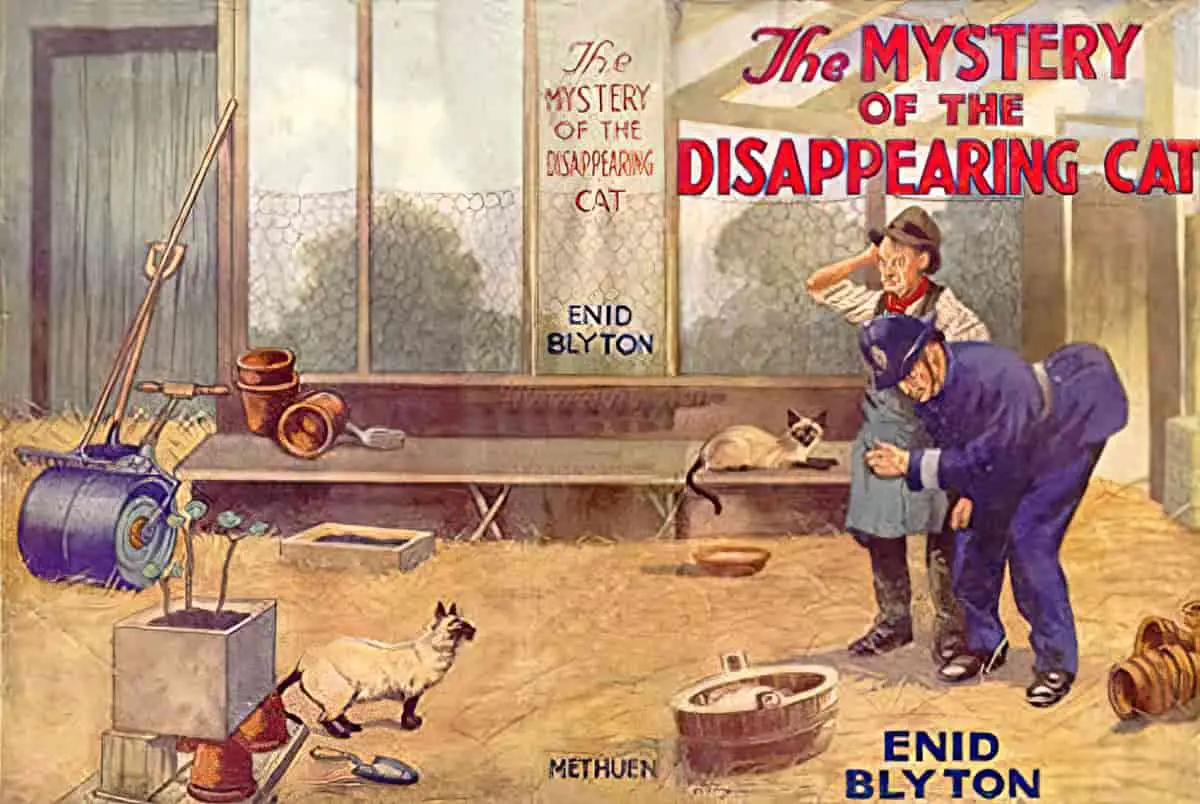

It’s easy enough to get parents out of the way, but aren’t police meant to be on call 24/7? Enid Blyton included numerous policemen in her stories and used them where it was convenient. But sometimes she tried to get rid of them.

Although Blyton tried to get rid of the police, leaving it up to Julian to lead the other children to victory, she didn’t always manage this successfully:

The plot has some small holes, as often happens in these children adventures. For example, once they discover the kidnapped person, the children do not go straight to the police. A reason is given for that, but it did not seem very convincing.

from a consumer review of the Ring o Bells Mystery

Enid Blyton can hardly be called contemporary, so let’s take a look at how Kate DiCamillo deals with police in her Mercy Watson series. The Mercy Watson series is set in 1950s-esque suburbia, functioning as a spoof of domestic bliss. Kate DiCamillo avoids problematic police altogether, but she does it by replacing them with firefighters.

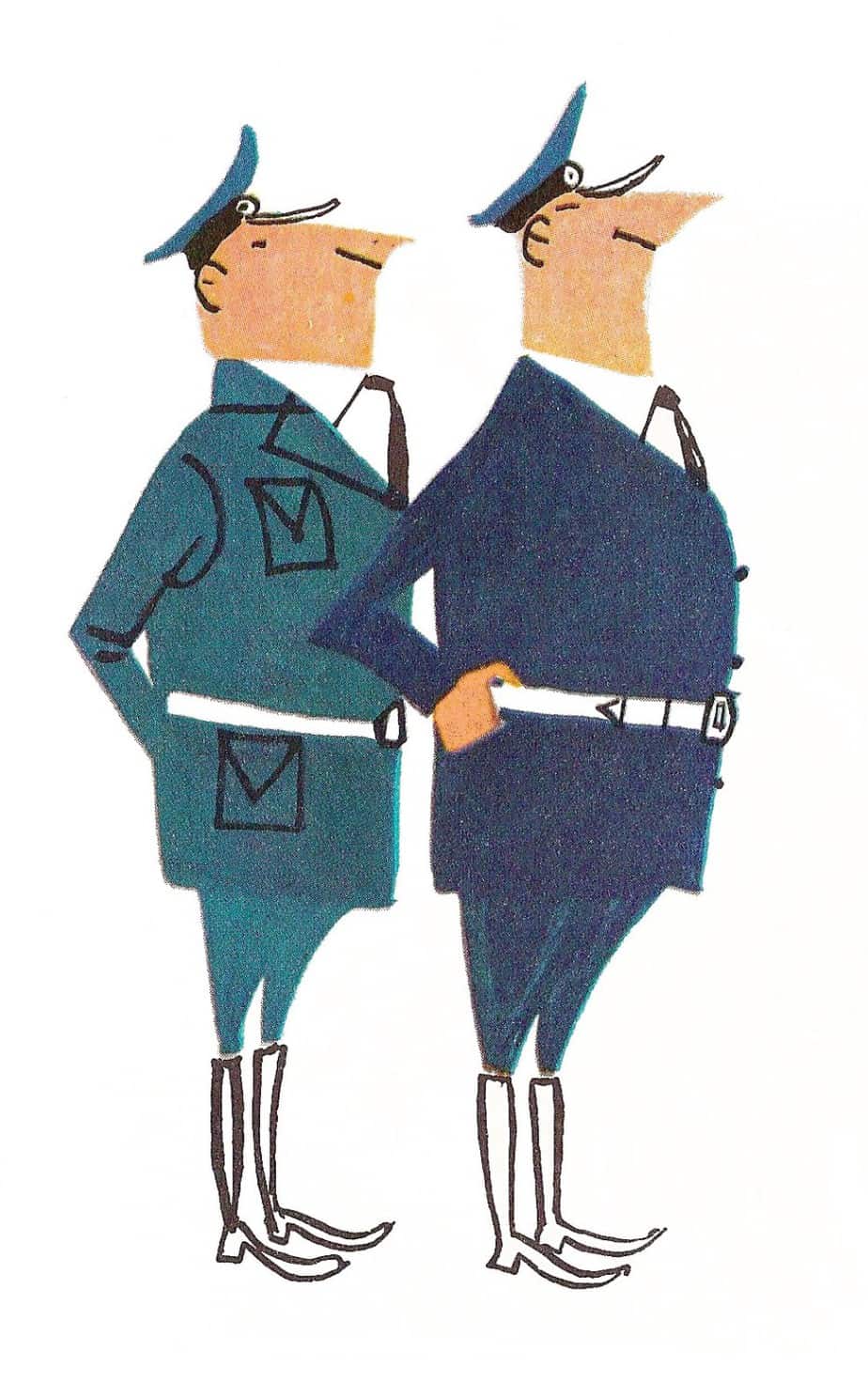

These two firefighters function identically to the policemen duos of Enid Blyton’s era and are called at the end of a story to finish off what has already been set in motion by the child and childlike characters.

To bring rescue teams too early to a children’s story would function unsuccessfully as deus ex machina, and agency removed from the child heroes. For various other examples of how police officers have been used in children’s stories see the following:

- Walter The Farting Dog in which a dog farts really stinkily and knocks out two Storybook Burglars. The police arrive immediately to deal with the burglars.

- The Tale of Pigling Bland or The Tale of Ginger and Pickles by Beatrix Potter from the First Golden Age of Children’s Literature. In the first example the police officer is roaming the country roads waiting for crime to happen. In the second example, the police officer is a creepy doll.

- “A Good Tip For Ghosts” by Paul Jennings uses the police officer as storyteller.

- Junie B. Jones And The Stupid Smelly Bus, in which Junie gets a lecture from the police officer

- “Lamb To The Slaughter” by Roald Dahl is regularly studied in high schools. In this story, the trickster murderer fools police officers, who are guided by their bellies. Though there are hints of bumbling policemen in children’s literature, by the time readers have hit the teenage years, their storybook cops are no longer the trustworthy archetypes who always know what’s what. Even in his children’s books, Dahl avoided the Storybook Police Archetype. See Matilda for an example in which police play a peripheral part — they exist to be avoided. Dahl had a mistrust of authority of all kinds, and was a large part of the movement towards subversive, darker middle grade fiction.

Header illustration by Mary Petty (1899-1976), 1943