The Shawl (1980) is a short story by American writer Cynthia Ozick, born 1928. In 2014, Joyce Carol Oates joined Deborah Treisman at The New Yorker to read and discuss Ozick’s story.

This horrific short story reminds me most of a narrative from another side of the same war: Grave of the Fireflies. Both are about starving, desperate war victims on a journey to nowhere. Both result in death from starvation. The Road by Cormac McCarthy has its similarities, including another horrific baby scene. (If you’ve watched the film adaptation and not read McCarthy’s novel, you have escaped it. The scene was clearly considered too harrowing for a film-going audience.)

Grave of the Fireflies utilises an empty box of sweets (replaced with stones) in the way Ozick utilises the corner of a shawl — the young starving character sucks on a non-food item as a way to quell their hunger. Both are grim motifs. The shawl in Ozicks’ narrative adds an extra layer, functioning metonymically for comfort spread thin.

SETTING OF THE SHAWL

“The Shawl” was first published in the print edition of the May 26, 1980 issue, but this is a story set 40 years earlier during The Holocaust. Ozick was moved to write this fictional short story after hearing a terrible real story about a baby thrown to its death against an electrified fence. If I didn’t know this backstory, I don’t think I would have picked up from the following sentence that this is what happens in the story:

Below the helmet a black body like a domino and a pair of black boots hurled themselves in the direction of the electrified fence.

The Shawl

Though we get a strong image of a baby electrified against a fence (compared first to a moth, then to a butterfly), the author has removed full agency from the soldier who did this. The body and boots ‘hurled themselves’.

Deborah Treisman points out that there’s something ‘fairytale’ about this story. The shawl is a magical item and can nourish a child for three days and three nights. The cannibalistic undertones and the black helmet also feel like something straight out of fairytale world. (We’re not talking about the bowdlerised Disney fairytales, but the dark ones from antiquity, meant for an adult audience.)

Oates adds that the rhythms of the language contribute to this fairytale feel because they emulate a dreamlike state, showing that the characters are entranced under a horrific spell.

CHARACTERS OF THE SHAWL

Cynthia Ozick wrote a lot about the Holocaust but only a small proportion of her writing has resonated with readers. This is considered a gem, leading to a sequel called “Rosa”, published by The New Yorker in 1983. Next came her book called The Shawl, published by Vintage. We find out in “Rosa” that Stella is actually Rosa’s niece, and Magda is a cousin, not her sister. We also find out that Magda was very likely the result of a rape by a German soldier. This is only suggested in “The Shawl” by the note that she looks Aryan.

The face, very round, a pocket mirror of a face: but it was not Rosa’s bleak complexion, dark like cholera, it was another kind of face altogether, eyes blue as air, smooth feathers of hair nearly as yellow as the Star sewn in to Rosa’s coat. You could think she was one of their babies.

The Shawl

To read the sequel, then, is to experience a revisioning of our take on this first story. (Delayed decoding.) Without reading the sequel we will assume this family comprises a mother and two daughters, but now that I know this I’ll have to include info included in “Rosa”.

Stella — 14 years old, ravenous with hunger. “Stella gave nothing; Stella was ravenous, a growing child herself, but not growing much.”

Rosa — Stella’s auntie and Magda’s mother. Raped by a German soldier, resulting in Magda, who looks Aryan. “Rosa was ravenous, but also not; she learned from Magda how to drink the taste of a finger in one’s mouth.” In several places, Rosa is described as a tiger for the way she guards her baby, thinking someone will eat her, then worrying that she’ll squash her with her thigh while sleeping. (Women are commonly compared to cats in fiction.)

Magda — a malnourished baby on the brink of death. In fact she should be toddling. She’s fifteen months old. Beacuse this is all she’s known, she sometimes laughs at small things, namely the shawl blowing in the wind. Her biological father is Aryan, the German enemy.

STORY STRUCTURE OF THE SHAWL

NARRATION

The story begins by focalising Stella’s point of view. She feels jealous of Magda. The narration then switches to Rosa’s perspective and that’s where Ozick keeps us. I call this sort of narration switch a variety of Hitchcock’s McGuffin, though when Hitchcock said ‘McGuffin’ he was only talking in terms of plot. Why would a writer decide to begin with one focaliser than switch to another?

In short stories, this trick is fairly common, but Oates, when asked, says that Ozick may not have had any idea why she did that. (I agree that when writers use sophisticated tricks, the tricks are not always performed consciously. It’s the separate work of the commentator to bring these tricks to consciousness.)

More interesting than guessing whether the author meant to switch narrators like this or not: What effect does it achieve for the reader? (It is never interesting to me, to try and guess what a storyteller ‘meant’; so much happens at the level of the subconscious.)

Rosa feels her niece is a potential cannibal, but because the story opened from Stella’s point of view, we know she is not. We know she is a regular, but starving hungry, teenage girl who wishes for comfort. Her longing is for the breast, not for baby meat.

SHORTCOMING

These women are in a horribly vulnerable position. They are considered vermin by people in power who would like to see them dead. That stakes can’t get much higher than this. The women are therefore traumatised, and we can deduce this trauma has been going on for a long time — over years.

DESIRE

We can deduce what these characters don’t want to be doing. We all share the need for personal freedom and also for sustenance. Though these characters desire freedom, it is the hunger that’s foregrounded in this particular moment of their long tragedy.

There’s a long fairytale history of women (especially step-mothers, ie. women who are not mothers) eating children and babies.

Rosa thought how Stella gazed at Magda like a young cannibal. And the time that Stella said “Aryan,” it sounded to Rosa as if Stella had really said “Let us devour her.” … She was sure that Stella was waiting for Magda to die so she could put her teeth into the little thighs. … she knew that one day someone would inform; or one day someone, not even Stella, would steal Magda to eat her.

The Shawl

The need for comfort is at its most basic with the baby:

The shawl was Magda’s own baby, her pet, her little sister. She tangled herself up in it and sucked on one of the corners when she wanted to be very still.

The Shawl

Stella’s need for comfort is expressed in the opening, when she looks enviously at a baby who has its mother’s breasts. This reminds me of a dream sequence in The Sopranos (The Isabella hallucinations). For Tony, breasts are sexual as well as maternal. There’s nothing sexualised about the breasts as maternal sustenance in “The Shawl”.

OPPONENT

The overarching enemy of these characters are Nazis and Nazi sympathisers but we don’t see them on the page. The Holocaust is shared human history, and the story takes for granted that we will understand the historical context with just a few details of setting.

For Rosa, everyone is a potential enemy. Hunger, she feels, turns people into animals. She must turn into a wild animal (a tiger) to protect her offspring.

PLAN

These characters are walking in a line and have no free will to do anything else during this story.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

Then Stella took the shawl away and made Magda die.

The Shawl

Now the story goes backwards in time to the moments before the death.

As in many lyrical short stories featuring death, this story is not a build towards the death scene but is about what happens afterwards. (William Trevor’s “Bravado” is another good example of this.) That the baby dies is not even used as a reveal; like Rosa, we know this is about to happen.

ANAGNORISIS

Are we to consider Stella culpable for the baby’s death? Oates says no, because of the fairytale magic, suggesting the world works how it works, and things happen.

I agree with Treisman that this is the most astonishing line from the story:

Every day Magda was silent, and so she did not die. Rosa saw that today Magda was going to die, and at the same time a fearful joy ran in Rosa’s two palms, her fingers were on fire, she was astonished, febrile: Magda, in the sunlight, swaying on her pencil legs, was howling.

The Shawl

We don’t expect a mother to feel ‘joy’ with the knowledge that her baby is about to die. That makes this sentence a prime example of ‘unexpected response’ in fiction. Part of the job of a work of fiction is to delve deep into our most complex emotions. In everyday life we tend to carve emotions into disparate concepts, but in reality, emotions intersect. It is possible to feel more than one thing at once, and sometimes those things are diametrically opposed: disgust plus attraction is one of the more commonly understood complexities of emotions, but here we have something even more confronting: Joy plus grief.

Why might someone feel joy in this situation, however small the spark? There’s a certain relief that comes with an ending. We rarely acknowledge that in discussions about death. It’s the job of fiction to acknowledge the unsayable.

Also unsayable: The possibility that Rosa had difficulty connecting to a baby who resulted from trauma and abuse, and who resembles her rapist, and who was born in traumatic circumstances.

This isn’t the first juxaposition of emotion to occur in the story. We saw it earlier with the baby laughing, even in these most dire circumstances:

Sometimes she laughed—it seemed a laugh, but how could it be? Magda had never seen anyone laugh. Still, Magda laughed at her shawl when the wind blew its corners, the bad wind with pieces of black in it, that made Stella’s and Rosa’s eyes tear. Magda’s eyes were always clear and tearless.

The Shawl

Another sentence uses ‘jolly’ in an unexpected place, right after Stella has taken the shawl:

Rosa saw and pursued. But already Magda was in the square outside the barracks, in the jolly light.

The Shawl

Likewise, the wind laughs:

Even the laugh that came when the ash-stippled wind made a clown out of Magda’s shawl was only the air-blown showing of her teeth.

The Shawl

Notably, via Rosa’s focalisation, the narrator compares her baby to a rat:

Even when the lice, head lice and body lice, crazed her so that she became as wild as one of the big rats that plundered the barracks at daybreak looking for carrion, she rubbed and scratched and kicked and bit and rolled without a whimper. But now Magda’s mouth was spilling a long viscous rope of clamor.

The Shawl

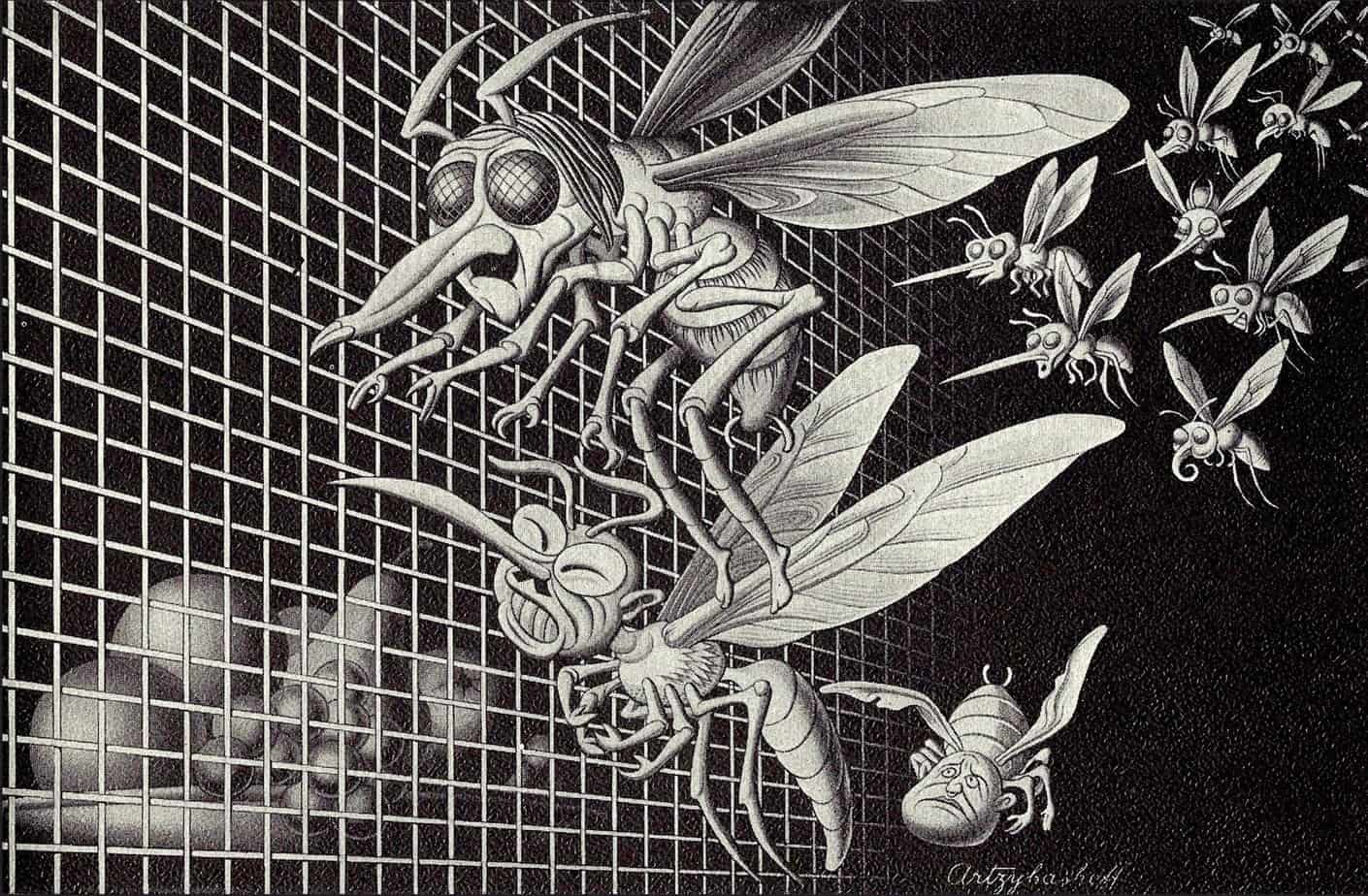

Though Rosa’s rat analogy is the pitying kind, comparing groups of people to vermin is a weapon of dictators and war mongerers. We see it still happening today. During WW2, Nazis compared Jewish people to rats as a way of dehumanising and othering fellow humans as a way of psychologically preparing their people for the mass murder of ‘other’ people.

In response, anti-war activists depicted Nazis as pestilent creatures, in the case below, flies.

NEW SITUATION

We have already been told that Rosa is so traumatised that her feelings have been numbed:

They were in a place without pity, all pity was annihilated in Rosa, she looked at Stella’s bones without pity.

The Shawl

Rosa makes a choice at this point. As is pointed out in the New Yorker podcast, Rosa’s choice is not a Sophies Choice variety of moral dilemma. This is not a moral dilemma in the true sense of the phrase:

A dilemma is a choice between two equally good or two equally bad outcomes. A moral dilemma elevates such a choice by giving two outcomes equally excellent, or excruciating, consequences not only for a protagonist, but for others. A dilemma is a situation in which none of us likes to be caught, but in which we all sometimes find ourselves. A moral dilemma is a situation nobody wants, and which few must ever face, but which is terrific for making compelling fiction.

Donald Maass

If Rosa were to give up and die now, in such horrific circumstances, this would be the easier option fo rher. Life and death are not balanced equally here.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

We can expect Rosa’s numbness to continue.

RESONANCE

There was talk in 1980s about whether Ozick should have taken someone else’s horrific experience and wrote about it even though she, herself, wasn’t there. We are still having this conversation, about who is permitted to tell whose stories, and I realise now that we may never settle on a clear answer to this.

The fear of being unable to protect one’s own baby is a universal and enduring fear, especially for new mothers. Emma Donoghue’s Room is another story of a mother and child in extraordinary (traumatic) circumstances, and also succeeds as an allegory for the depths of emotions around bringing a child into the world and feeling solely responsible for them.

Header painting: Jessie MacGregor – In the Reign of Terror, 1891.