The purpose of fiction genre is to help readers find the stories they want.

For a full list of Fiction Genres you can’t go past the Wikipedia article. These are my own notes on genre, incomplete, but with a different spin.ga

Children’s literature is broken down into genres, just as adults’ stories are. But critics of children’s literature differ in how they prefer to categorise the main types of stories for children.

I’ve observed that children’s editors and similar often avoid talking about ‘genre’ when discussing children’s stories. ‘Genre’ is one of those words that needs quote marks around it. Instead, they use different terminology.

Peter Hunt divides stories for children into three main groups depending on the type of ending: closed, semi-closed, unresolved. When talking about adult genre, not many types get their own category dependent upon ending. A notable exception is ‘dystopian’. Dystopian stories have, well, dystopian endings.

Children’s Fiction — Not a genre but a category. Some writers tell you children’s literature is qualitatively different from adult literature. Others say the difference is overblown.

Children’s books are also sometimes referred to as a ‘genre’: “The genre has come a long way over four centuries. Early children’s books tended to be solemn and purposeful,” Marcus says. “They were created to teach a moral lesson of some kind and they spoke to the child from on high.”

The Atlantic

Academic Maria Nikolajeva does not make a distinction between:

what is normally described as ‘genres’ or ‘kinds’ of children’s fiction: historical fiction, fantasy, adventure, realistic everyday story, or “nonsense” (which I do not believe to be a generic category anyway, but rather a stylistic device). The difference is in setting, or more specifically in chronotope, the organisation of space and time. In my typology, all these texts belong to the same narrative pattern: “semiclosed” in Peter Hunt’s taxonomy, “Odyssean” in Lucy Waddey’s. In Frye’s mythical cycle, the closest description is romance.

(Chronotope is Bakhtin’s terminology.)

A CASE FOR IGNORING GENRE

LIST OF TYPES, CATEGORIES AND FICTIONAL GENRE

ACTION

The main character has a clear goal: to recover something, to rescue someone, to beat a baddie against the clock… Good action main characters go at their goal like unstoppable horror robots. They have a vast reserve of energy.

Action films tend to come out in summer.

Anti-Western

Since WW2, almost every “Western” is actually an anti-Western. Rather than romanticising the expansion into the West, anti-Westerns focus on the harshness of the landscape, the death and the despair. Because modern audiences are so used to this kind of Western, we tend to simply call anti-Westerns “Westerns” now.

AUTOFICTION

Autofiction is a form of fictionalized autobiography, combining autobiography and fiction.

The term autofiction has been in vogue for the past decade to describe a wave of very good American novels by the likes of Sheila Heti, Ben Lerner, Teju Cole, Jenny Offill, and Tao Lin, among others, as well as the multivolume epic My Struggle by the Norwegian Karl Ove Knausgaard. These are books that invite readers to imagine they might be reading something like a diary, where the transit from real life to the page has been more or less direct.

Sheila Heti, Ben Lerner, Tao Lin: How ‘Auto’ Is ‘Autofiction’? at Vulture

Buddy Detective

A buddy story featuring two detectives at work.

Broadchurch takes the classic buddy detective template (she’s by the book, he plays by his own rules) and gives the procedural depth by showing the emotional aftermath of an unspeakable crime (drama).

Buddy Story

A story featuring two main characters who are buddies. These two buddies will be quite different in personality, creating lots of natural conflict (often comedic), but ultimately their deficiencies will fuse together nicely and allow for a happy ending.

The ‘buddy movie’ equivalent in middle grade literature is also pretty popular. The buddy movie is really a mixture of three genres (Action + Love + Comedy), or if it’s a buddy cop movie it’s Action + Love + Crime, and we’re seeing this first kind of genre mashup in series such as Jeff Kinney’s Diary of a Wimpy Kid, with Greg Heffley as the main character who has a more naive and light-hearted best friend.

The same combination is used in Monster House (the film). Usually, girls form the opponents, and are seen as a different species. This is supposed to result in humour, to a greater or lesser extent.

Though not really a kids’ story due to the advanced age of the narrator, The Wonder Years gives us Kevin Arnold and his best friend Paul. The comedy that results is of a melancholic kind.

Nowadays, the female buddy movie is starting to be made, perhaps because gender-swapping is one easy way to do something a bit different. For example, we have Bullock and McCarthy in It Takes Two. So it follows that we’ll start to see more buddy MG stories with female leads, though there are perhaps still too few stories about female friendship, especially when it comes to comedy. Female friendships and the problems within are almost always treated in dramatic/serious fashion.

Child In Jeopardy Thriller

From the point of view of a vulnerable parent (usually a woman) who must risk her life to save her child

COMEDY

Comedy has its own subgenres, mostly:

- action

- buddy

- traveling angel

- romantic

- farce

- black

- satire

- crime

- detective

Coming-of-age

Maria Nikolajeva describes children’s stories as ‘a symbolic depiction of a maturation process (initiation, rite of passage) rather than a strictly mimetic reflection of a concrete “reality”.’

Arguably the most pervasive theme in children’s fiction is the transition within the individual from infantile solipsism to maturing social awareness’.

John Stephens

See my post on Coming-of-age Stories. (In which there are subcategories and related categories.)

Climate Fiction

The category of story is typically a mixture of drama, thriller, horror and perhaps science fiction, though I think the phrase ‘speculative fiction’ is a better descriptor because creators of climate fiction don’t want audiences to think that climate change isn’t real. They tend to want action, and to spur behavioural change.

Climate fiction (sometimes shortened as cli-fi) is literature that deals with climate change and global warming. … The genre frequently includes science fiction and dystopian or utopian themes, imagining the potential futures based on how humanity responds to the challenges created by climate change.

Wikipedia

Terror, hope, anger, kindness: the complexity of life as we face the new normal:

In the faces of the bushfire victims we saw ourselves and our shared future. We can no longer shy away from reality by James Bradley

Cosmogonic Myth

In mythology, creation or cosmogonic myths are narratives describing the beginning of the universe or cosmos.

Some methods of the creation of the universe in mythology include:

- the will or action of a supreme being or beings,

- the procss of metamorphosis,

- the copulation of female and male deities,

- from chaos,

- or via a cosmic egg.

Contemporary Realistic Fiction

The characters are made up, but their actions and feelings are similar to those of people we could know. These stories mostly have contemporary settings and deal with contemporary concerns.

Crime

Whereas detective stories are about getting the truth, crime stories tend to feature the chase aspect of tracking down a criminal.

Crime is popular worldwide, for children and adults alike.

Enid Blyton wrote a lot of detective stories (The Famous Five, Secret Seven). Detective stories continue to be popular, and below the upper-MG age group, it’s the subgenre of ‘cosy crime‘, in which the stakes are low. (See Alexander McCall Smith’s The Great Cake Mystery). In the world of children’s books, Nate the Great is known for his:

unflinching resolve in the face of stolen goldfish, absconded cookies, and M.I.A. pets.

A combination of drama and cozy crime is common in children’s literature. Timmy Failure by Stephan Pastis seems to have its main genre as drama, with a sub-genre of crime:

It doesn’t take much reading between the lines to discover that Timmy has real problems: his grades are poor, he’s not very popular, and his single mother is struggling to pay the bills while her new, thuggish boyfriend is making Timmy’s home life unbearable. Investigating a case of a missing Segway with his (imaginary) polar bear business partner makes for a good diversion.

See: The 15 Greatest Kid Detectives from Huffington Post

Sammy Keyes is described likewise as a:

skillful mix of mystery with a traditional coming-of-age narrative

Like the trend in stories for adults, children’s books now are often described as a blend between one type of story and another in the marketing copy:

Like The DaVinci Code meets From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler, Chasing Vermeer is chockablock with mind bending puzzles and tantalizing twists that readers will gobble up along with Petra and Calder.

Daniel Handler’s series All The Wrong Questions is described as…

a pitch-perfect update of the pulp fiction crime novels from the 1930s meant for young audiences.

“Everything’s a mash-up”, or builds on what has come before, sometimes with an ironic knowingness, at least, for older readers who have read the originals:

Mac Barnett’s playful riff on The Hardy Boys makes good fun of skewering the boy-detective genre while still offering a mystery that’s quick-witted and engaging.

Is it true for children’s literature, as it is for Hollywood scripts, that stories must nowadays be a blend of more than one genre?

The Girl Who Could Fly is blurbed as follows:

It’s the oddest mix of Little House On The Prairie and X-Men.

…in acknowledgment of the observation that historical fiction mixed with superhero plotting (which is really a type of myth) is quite unusual.

I’m not convinced that children’s books need to be more than a single genre, for the simple reason that a younger audience has not yet had the breadth of media exposure to have become sick of single genre stories. Picture books are often a single ‘genre’ most of the time, because they are so short.

It’s certainly true that in children’s literature, publishing goes through phases and evolutions. Everything builds upon what’s come before, and when a straight love story becomes so common that it’s hard to do something new with it, we get another spin.

DETECTIVE

Detective stories are about finding the truth. Compare with crime and you’ll find the reveals happen in reverse chronological order.

This Is Not My Hat by Jon Klassen could be described as a detective story.

DISASTER

Disaster stories are called ‘panic films’ in Japan. This genre takes its name from the setting, which is sometimes a natural disaster such as a tornado, flood and sometimes a disaster caused by humans e.g. acts of terrorism. Zombie stories and Italian cannibal movies count as subcategories of disaster stories. Disaster stories are popular because they often say something positive about humanity.

In the aftermath of every disaster, you see these amazing expressions of love. People risk their lives to save others. I’m describing a sort of abundance love, a love without scarcity. I’ve covered enough disasters to know that this is a profoundly human impulse. When disaster strikes, people are not asking, “Are you Christian? Are you Muslim? Are you related to me?” People are just faced with taking extraordinary risks to save each other, whether it is a home-care worker saving the life of the elderly person who they’re taking care of or whether it is somebody risking their life to save somebody else’s kids.

Naomi Klein

Disaster stories are sometimes about real historical events. In this case, there can be ethical issues with creating spectacles for entertainment when there are real victims. To be successful with a wide audience, disaster stories must secure “aesthetic disinterestness”. Catastrophic events are rendered awful but tameable.

In watching a disaster via a story, we measure ourselves against the omnipotent power of nature.

But disasters are sublime events. Philosopher Kant had plenty to say about the sublime. He believed humans aren’t really capable of grasping the magnitude of disasters.

There’s a podcast all about disaster movies called Disaster Pod. (@disaster_pod on Twitter)

DOCUMENTARY

Stories Make the World: Reflections on Storytelling and the Art of the Documentary

As an award-winning documentarian and writer, Stephen Most has a great deal of experience in the art of storytelling with non-fiction films. In Stories Make the World: Reflections on Storytelling and the Art of the Documentary (Berghahn Books, 2017), he examines how documentary filmmakers work to present reality and truth using storytelling concepts that stretch back through time.

New Books Network

Reclaiming Popular Documentary

The documentary has achieved rising popularity over the past two decades, thanks to streaming services like Netflix and Hulu. Despite this fact, documentary studies still tends to favor works that appeal primarily to specialists and scholars. Reclaiming Popular Documentary (Indiana UP, 2021) reverses this longstanding tendency by showing that documentaries can be–and are–made for mainstream or commercial audiences. Editors Christie Milliken and Steve Anderson, who consider popular documentary to be a subfield of documentary studies, embrace an expanded definition of popular to acknowledge documentary’s many evolving forms, including branded entertainment, fictional hybrids, and works with audience participation. Together, these essays address emerging documentary forms–including web-docs, virtual reality, immersive journalism, viral media, interactive docs, and video-on-demand–and offer the critical tools that viewers need in order to analyze contemporary documentaries and consider how they are persuaded by and represented in documentary media. By combining perspectives of scholars and makers, Reclaiming Popular Documentary brings new understandings and international perspectives to familiar texts using critical models that will engage media scholars and fans alike.

New Books Network

DOCUSOAP

a form of reality TV which purports to be a documentary following people in a particular occupation or location over a period of time e.g. workers at an airport. An apparent plot is constructed by intention or editing.

Dystopia

Is dystopia a genre?

Dystopian novels become a genre of their own, in which adults, politicians and leaders are consistently portrayed as deceitful, greedy, vainglorious and wicked. Occasionally, as in Sally Gardner’s Maggot Moon, the dystopia portrays an alternative history – a Fascist 1950s Britain along the lines of 1984. More usually, they are set in the future, against the cataclysms produced by current trends.

Dystopia isn’t new: in my own childhood there were superb writers such as John Christopher, whose Prince in Waiting trilogy should be much better-known. But these futures were the product of natural catastrophe or alien invasion. Now, the darkness and violence of contemporary dystopias is highly politicised. The most famous is Suzanne Collins’s The Hunger Games, in which teenagers are required to fight to death for the ultimate TV reality show. Or, you might say, the ultimate high-school show-down. Plenty of other terrific novels such as Scott Westerfeld’s Uglies, Malorie Blackman’s Noughts and Crosses, Meg Rosoff’s How I Live Now and Moira Young’s Blood Red Road depict our future as ravaged by science, racism, war, genetic mutation or most credibly, exams.

Amanda Craig, writing about the Third Golden Age of Children’s Literature

Until recently dystopia has been popular in YA. (Editors are recently saying they don’t want to read any more of it.) In the year 2000, Maria Nikolajeva wrote:

Dystopia has been by definition an impossible genre in children’s fiction. However, a recent trend in children’s fiction shows tangible traits of dystopia. We can see forerunners of this trend in post-disaster science-fiction novels, for instance. The Prince in Waiting trilogy, which combines high technology with medieval mysticism. In the trend I am referring to, the dystopian idea is central, the kernel of the story itself, and the interrogation of modern—adult—civilisation in these books is as strong as in Huxley or Orwell. It has taken children’s fiction more than half a century to catch up with adult literature in developing this genre, which contradicts the view of childhood as a vision of a hopeful future. It is amazing that the genre has become so prominent, indeed one of the most prominent genres in British, American, and Australian children’s fiction of the 1990s. An early representative of this trend may be seen in Robert Cormier’s I Am the Cheese, where a ruthless totalitarian society is reflected in a mentally disturbed boy’s mind. In Germany, Gudrun Puasewang has received much attention for her dystopian children’s novels, especially Fall-out, a gloomy post-Chernobyl depiction of a nuclear plant accident.

Dystopia might instead by considered a ‘category of ending‘ (grim rather than happy — the opposite of idyll) rather than a genre per se, with the most popular dystopian YA in 2015 being a blend of action, romance, myth and historical. For more on Dystopian fiction, see this post.

ESPIONAGE THRILLER

About spies doing their jobs (e.g. The Americans)

ELEVATED HORROR

“Elevated” horror is generally classified as a recent breed of filmmaking that eschews conventional jump-scares and gory imagery, instead disturbing audiences—many of whom self-identify as broader cinephiles as opposed to horror movie enthusiasts or more casual moviegoers—through immense emotional and psychological turmoil.

THE HACKNEYED HAG: THE MONSTER MOST EMBLEMATIC OF THE PAST DECADE OF HORROR IS A NAKED OLD WOMAN by Natalia Keogan

EPIC

Sohini Sarah Pillai talks about epics, long narrative poems about heroic events – whether all such poems can be called epics, and how they continue to generate cultural and political material. The conversation covers epic poems ranging from the Iliad to Jack Mitchell’s The Odyssey of Star Wars.

High Theory Podcast

FACTION (NON-FICTION NOVEL)

Faction is a genre devised by Truman Capote to describe his novel In Cold Blood. Others call it a non-fiction novel. Authors take real people and actual events, but weave them together like a novel. Dialogue will typically be fictionalised, for example, since the author has no way of knowing exactly what was said in private or historical situations.

FAKE RELATIONSHIP ROMANCE

There’s a romance subgenre called ‘fake relationship’. Two people are forced into emotional closeness via proximity or circumstance.

Muriel’s Wedding doesn’t quite fit this category of romance because it transcends these stories and becomes a story about female friendship instead. There is no girl-meets-boy happy ending, which propels it out of the romance genre.

Fantastic

Tzvetan Todorov (1939 – 2017) was a French and Bulgarian literary theorist and cultural critic who is known for defining the genre of ‘the fantastic’ in fiction. According to Todorov, fantastic is separate from fantasy. The fantastic sits between the uncanny and the marvelous. The fantastic requires a moment of hesitation between belief and disbelief of the supernatural. If it doesn’t have that specific thing, it’s not fantastic. (It’s a narrow genre.)

The fantastic occupies the duration of this uncertainty. Once we choose one answer or the other, we leave the fantastic for a neighboring genre, the uncanny or the marvelous. The fantastic is that hesitation experienced by a person who knows only the laws of nature, confronting an apparently supernatural event. […] “‘I nearly reached the point of believing’: that is the formula which sums up the spirit of the fantastic. Either total faith or total incredulity would lead us beyond the fantastic: it is hesitation which sustains its life”.

The Fantastic: A Structural Approach to a Literary Genre

However, ‘fantastic’ also happens to be the adjectival form of ‘fantasy’. So if you hear someone talk about fantastic fiction, they may be talking about fantasy, or they may be talking about Todorov’s very specific (and possibly outdated) definition. (After all, Todorov thinks the fantastic ended with Edgar Allan Poe.)

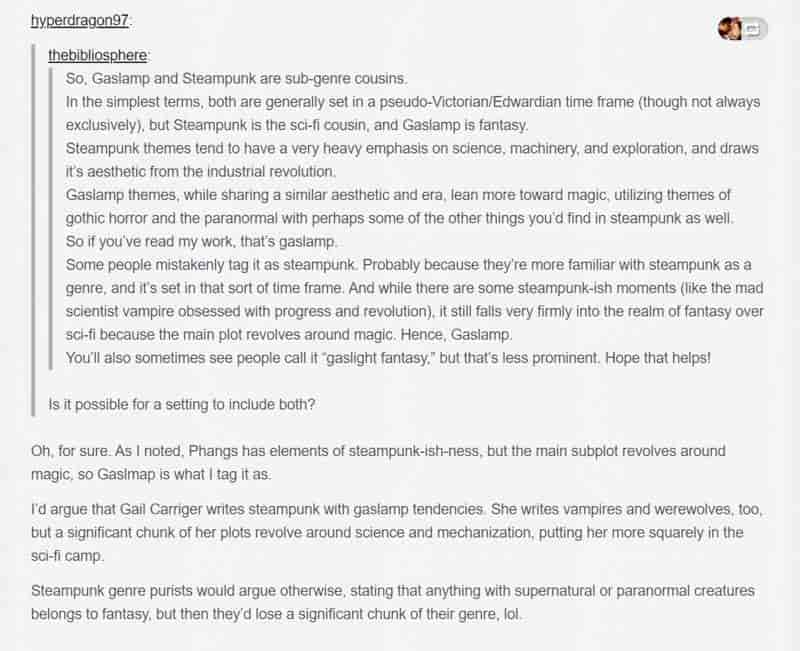

FANTASTIKA

The category includes Fantasy, Science Fiction and Horror but also Alternative History, Gothic, Steampunk, Young Adult Dystopian Fiction and other stories which display radical imagination.

The term comes from a range of Slavonic languages. John Clute introduced it into English.

FANTASY

When we talk about fantasy we generally mean magic and unreal worlds. What is the fantasy genre for? Fantasy allows characters (and readers) to explore hidden possibilities. Fantasy also tends to be about how society might open itself up to new possibility.

England has produced some of the most outstanding fantasy over the last century or so, whereas America is known for its realism. This is starting to change.

FOLK HORROR

Folk Horror uses elements of folklore to invoke fear and foreboding. The most popular examples are:

- anthropocentric

- with a focus on unwitting outsiders

- who are brutally sacrificed

- after stumbling into a rural, pagan community

The Ritual (2017) is a good contemporary film example, along with Stephen King’s short story “Children of the Corn”. See also:

- The Wicker Man (1973) by Robin Hardy

The prevailing consensus is that this type of folk horror revolves around conflict between the modern/urban/global outsider and the rural/’pagan’ community. The rural communities are primitive while the urban outsiders are sophisticated, to their downfall.

That said, not all folk horror fits this pattern. Another far more recent Stephen King story called “In the Tall Grass” (2012) co-written with his son Joe Hill, does not put people at the centre.

The TV series Children of the Stones (1977) is another example of folk horror which is not anthropocentric.

In this category of folk horror, humans are nonetheless present, if only because they have been displaced from their central role. These stories offer a critique on how much damage humans have on their environment.

Another way of looking at folk horror (Adam Scovell, 2017) is via the ‘Folk Horror Chain’ of events:

- landscape

- isolation

- a skewed belief system

- the happening or summoning (an often violent and sometimes supernatural culminating event)

FINANCIAL THRILLER

Thrillers about investors doing their jobs

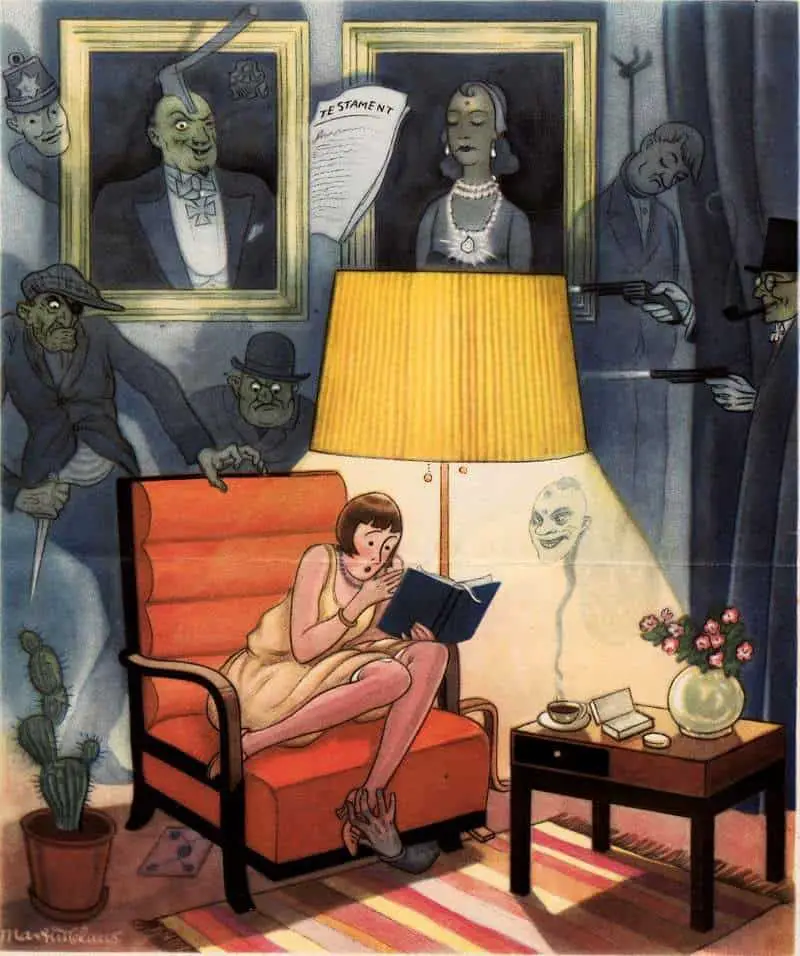

GASLAMP

GEEZER TEASER

A microgenre specific to the film industry: Fast-n-cheap films made with former A-list action stars, often centred in the promo but barely present in the film. (Bruce Willis’s career)

GHOST STORY

In his 2008 essay “M.R. James and the Quantum Vampire: Weird; Hauntological: Versus and/or and and/or or?” China Mieville says that the term ‘ghost story’ is overused. Many ghost stories don’t have ghosts in them. This is true. A lot of them have monsters instead.

It’s also true that fairy tales don’t often have fairies in them.

Gothic Horror

GOTHIC SUSPENSE

GRIMDARK

And speaking of Alan Moore, let’s talk about Watchmen because that book is single-handedly responsible for realism being modern shorthand for grimdark and misery where “grimdark” is a blanket term that covers amorality, gratuitous violence, and a general bad time for all involved.

Red at Overly Sarcastic Productions

HAGSPLOITATION

A microgenre specific to the film industry: Horror, often starring former glamour actresses behaving in sadistic/delusional way. Also known as psycho-biddy. e.g. Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?

HITCHCOCK THRILLER

If you’re using many of the same techniques used by Hitchcock, you’re probably writing a Hitchcock thriller. Techniques include: the Macguffin as inciting incident, the sense that you’re a voyeur into someone’s private life, the sense of psychological unease running throughout, and the false ending (or ‘climactic plot twist’).

Horror

Horror is designed to create that feeling of horripilation in viewers/readers. The hair stands up on the back of the neck. But is that all it’s for? No, horror is more generally about humans reduced to animals or machines because we are attacked by an Othered outsider (often a supernatural monster).

The Goosebumps series is the childhood equivalent of horror, though it will have to be lumped into Fantasy.

JOURNALISM/CONSPIRACY THRILLER

Thrillers about journalists doing their jobs

LEGAL THRILLER

About lawyers doing their jobs (A lot of John Grisham novels)

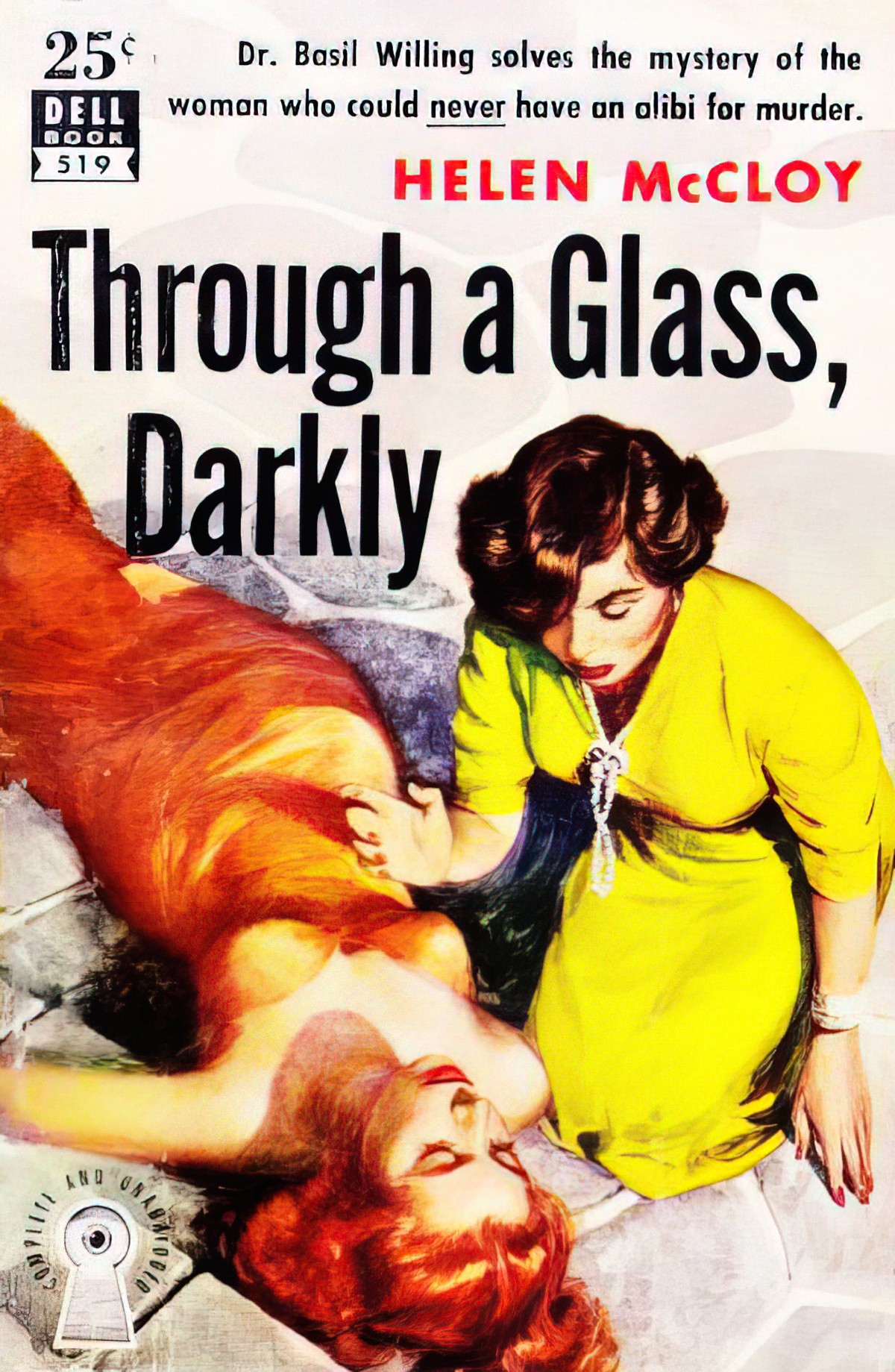

LESBIAN PULP

Locked Room Mystery

The “locked-room” or “impossible crime” mystery is a subgenre of detective fiction in which a crime (almost always murder) is committed in circumstances under which it was seemingly impossible for the perpetrator to commit the crime or evade detection in the course of getting in and out of the crime scene.[1] The crime in question typically involves a crime scene with no indication as to how the intruder could have entered or left, for example: a locked room. Following other conventions of classic detective fiction, the reader is normally presented with the puzzle and all of the clues, and is encouraged to solve the mystery before the solution is revealed in a dramatic climax.

Wikipedia

Poirot Solves A Murder On The Orient Express by Agatha Christie is a good example. Trains make a good setting for a ‘locked room’, since the criminal can’t easily disembark while the train is en route.

LitRPG

Literary role playing game.

Like the old Choose Your Own Adventure (a copyrighted term) but makes use of game mechanics and encourages interaction with friends. Stories tend to be science fiction and fantasy, and there’s a big fan fiction community.

Love

In love stories, the main opponent is also the person the main character wants to be with. This is one of the reasons why love stories are difficult to plot.

Picture books are often about the love between children and their families. In middle grade there is often the hint of a love subplot. In young adult stories, you get the entire range of love story, including sex.

We’re seeing more and more adult genre elements working their way into YA, perhaps because a large proportion of YA is read by adults:

This is not your parents’ Nancy Drew mystery. While there are elements of Nancy and her gang in all mysteries subsequent, the real inspiration I see in the current growing subgenre of what I have dubbed PG-13 Serial Killer Fiction, is the lead character of Veronica Mars, with a hint of Buffy the Vampire Slayer and just a dash of the adult serial killer chaser fiction like James Patterson’s Alex Cross series. Truly, the hunt for mass-murdering sociopaths does not sound like traditional young adult literature, however, I have noted the trend growing in recent years of bringing these tales to the new generation of readers by featuring empowered teenage females with unusual gifts as the foil for the killer. [In true Thriller fashion.]

review of I CAN NOT TELL A LIE BY JOSH NEWHOUSE at Nerdy Book Club

Marvelous — Unlike the uncanny, the marvelous does not require a response from a character, only that the fantastic event occurs. The marvelous is the supernatural accepted as supernatural. (Compare with the uncanny, in which the supernatural is explained.)

MEDICAL THRILLER

Thrillers about doctors doing their jobs

Melodrama

MEMOIR

The key genre expectation of memoirs is that the story is an attempt at truth and reflection through the autobiographical eyes of the author. An autobiography tends to be more linear in its unfolding of events whereas a memoir is more of a non-linear collection of memories.

Memoirs are governed by the idea that subjective truths can stand in for more universal perspectives. True crime memoirs take this idea to a greater extreme, as writing about the worst thing that has happened to you—rape, the murder of a loved one, or some other horrific type of violence—offers broader meaning for those who have survived similar events, and those wishing to understand how it’s possible to survive them.

Sarah Weinman

MILITARY THRILLER

Thrillers about army personnel doing their jobs e,g, 1917

Mockumentary

a television programme or film which takes the form of a serious documentary in order to satirize its subject.

Below, in critiquing Modern Family, Laurence Barber gives us a brief history of the mockumentary:

There is no evidence whatsoever to support the idea that Modern Family broke ground in terms of anything at all. Its use of the mockumentary format came long after the success of Spinal Tap saw it bleed into television; Australia’s own The Games (which aired in 1998) was one of the most prominent early mockumentary sitcoms, which was followed shortly thereafter by the massive success of Ricky Gervais’ original The Office. Not only was Modern Family beaten by these shows, but also the likes of Reno 911! and Chris Lilley’s We Can Be Heroes (as well as Summer Heights High). It’s never even been the best mockumentary currently airing, having run alongside the superlative Parks & Recreation since 2009. So the demonstrably false assertion of Modern Family’s format being ground-breaking aside, it’s necessary to question the idea that its “topic” broke any ground either.

Laurence Barber

MODERN FANTASY

The events, settings, or the characters are outside the realm of possibility. The author must convince the reader to suspend disbelief by creating an internally logical and consistent world. Modern fantasy itself breaks down into further subcategories:

- the re-visioned fairy tale (by a known author)

- animal fantasy, personified toys and objects

- quest stories and high fantasy

- time travel

- stories about miniature worlds and people

MONTAGE NOVELS

Montage novels are a type of Modernist novel which are ‘cinematic’, but we shouldn’t conclude that cinema was influencing the novel. It’s just as likely the other way around — the word ‘montage’ was not invented for cinema.

Mystery

MYTH/QUEST

A myth crosses cultural boundaries. The symbolism of myth runs deep and is shared interculturally. We might call it a ‘foundation genre’.

Northrop Frye writes in terms of ‘myth-to-romance—romance to high mimetic—low mimetic to ironic’.

Maria Nikolajeva writes about children’s stories in terms of ‘utopia–carnival-collapse’. Nikolajeva is also careful to provide the disclaimer that whatever may be true for stories in the West is not necessarily true when it comes to the structure of stories in other cultures.

Quest stories have a mythic structure. Nikolajeva writes of the Quest Story as a category of its own, if not a genre. Quest stories are stories of growth and maturation (and this is true whether the audience is adult or child).

Maria Nikolajeva notes that ‘a psychological quest for self can be found in many contemporary young adult novels, for instance Gary Paulsen’s The Island, a modern Robinsonnade. Examples of a children’s Robinsonnade would be Theodore Mouse Goes To Sea and Sailor Dog.

When applied to children’s literature, Nikolajeva prefers the term ‘picnic‘ in place of ‘quest’ because in children’s stories there is often no character development once the children come back to the primary world. For instance, the Pevensie children in the Narnia Chronicles live entire lives, then presumably live again as children when they arrive back in the real world.

NAUTICAL GOTHIC

‘Nautical’ generally refers to the oceans, but from a distant point of view, as if we’re viewing the ocean through the very specific view of a sailor’s telescope. A related word is ‘maritime’, but ‘maritime’ has connotations of piracy, defence and trade. ‘Marine gothic’ might be a broader and more suitable term to describe these dark tales that take place at sea.

Whatever we might personally choose to call this category of story, about the Other we find in the sea, the term ‘nautical gothic’ seems to be most written about in academic papers recently.

Necroromanticism

Jonathan Dollimore has argued that death and desire share an implicit connection, and Paul Westover has more recently discussed an eighteenth-century phenomenon that he terms necroromanticism, “a complex of antiquarian revival, book-love, ghost hunting, and monument building.”

Nowell Marshall

Neo-Western

a subgenre of the Western that adopts the character archetypes, settings, and themes of classic Westerns, but transplants them to appeal to contemporary sensibilities.

NOIR

It can be argued that noir is not a genre, but an atmosphere. There are certain conventions which make a film feel ‘noir’ — the strong contrasts between light and dark is one thing. Heavy reliance on first-person point-of-view is another.

Film School Rejects shared a short film called Gumshoe, which is four minutes shot from a first person point of view.

First person POV can be tricky to pull off because of how limiting the field of view is. It’s the same thing with found footage, but even without the shaky cam (or at least a less shaky cam), it can be disorienting and leave an audience frustrated by the loss of control. When it’s done well, it can be very cool. Still a gimmick, but an entrancing one.

Film School Rejects

In the noir film above, the first person point of view serves several purposes and one of those purposes is to add a comic (as well as comical) tone. The ‘kapow’ type voiceovers add to this humorous tone. A woman’s legs viewed from the top-down quash any real attempt at the familiar ‘sexy pose’.

Nonsense Stories

Maria Nikolajeva offers The 35th of May as an example of a story oft described as ‘nonsense’. ‘This funny, entertaining story has certainly been admired by many readers in many countries, but it has nothing to do with the idea of spiritual growth’. Is there an adult-analogue for the nonsense story? As explained above, nonsense is a stylistic device rather than a genre as such.

Odd couple

A story that pairs two characters whose personal, social or ethnic differences stop them from reaching an agreement or a common goal. The device is used frequently in comedy, or for dramatic tension. Odd couple ensembles are a subgenre across many genres: significantly in comedy, drama, action and Westerns.

POLITICAL THRILLER

About politicians doing their jobs (The Killing is an interesting blend of political and serial killer thriller). Political thrillers are not as popular with audiences.

PSYCHOLOGICAL THRILLER

These emphasise the unstable psychological and emotional states of their main characters. There are similarities to Gothic and detective fiction:

- A dissolving sense of reality.

- The setting is usually domesticated.

- The main characters are usually obsessed, tortured or sociopathic.

- Unreliable narratives are common. e.g. Psycho, Homeland, pretty much everything by Stephen King, Henry James, Patricia Highsmith.

PICARESQUE

Rather than genre, Nikolajeva thinks of children’s literature in terms of ‘quest’ and ‘picaresque’.

Quest has a goal; picaresque is a goal in itself. The protagonist of a picaresque work is by definition not affected by his journey; the quest (or Bildungsroman) is supposed to initiate a change. There is, indeed, sometimes a very subtle boundary between ‘there-and-back’ and a definite, linear journey ‘there’, which is best seen in the last volume of the Narnia Chronicles.

Picaresque: relating to an episodic style of fiction dealing with the adventures of a rough and dishonest but appealing hero. An example of a modern picaresque film for adults is Thelma & Louise.

Nikolajeva further categorises children’s fiction into three general forms:

- Prelapsarian (when the main characters are unspoiled by ‘The Fall of Man’. The setting tends to be pastoral, secluded, autonomous. The main characters tend to be ensembles. The narrative voice tends to be didactic and omniscient. Time is circular, with much use made of the ‘iterative’ rather than the ‘singulative’. Utopian fiction introduces readers to the sacred e.g. The Secret Garden.)

- Carnivalesque (in which the characters temporarily take over from figures of authority and often make mischief, but control their own worlds for a time. See: The Hobbit, Narnia Chronicles, Harry The Dirty Dog. Carnivalesque texts take children out of Arcadia but ensure a sense of security by bringing them back. They allow an introduction to death, which inevitably follows the insight about the linearity of time.)

- Postlapsarian (in which a pastoral setting tends to be replaced by an urban one, and collective protagonists are exchanged for individuals. First person point of view is common. Time is linear. The main character knows that time is linear, so death becomes a central theme. Harmony gives way to chaos. The social, moral, political, and sexual innocence of the child is interrogated. These texts exist to introduce children to adulthood and death, and encourages them to grow up, or helps them out with it. In these stories, there is no going back.)

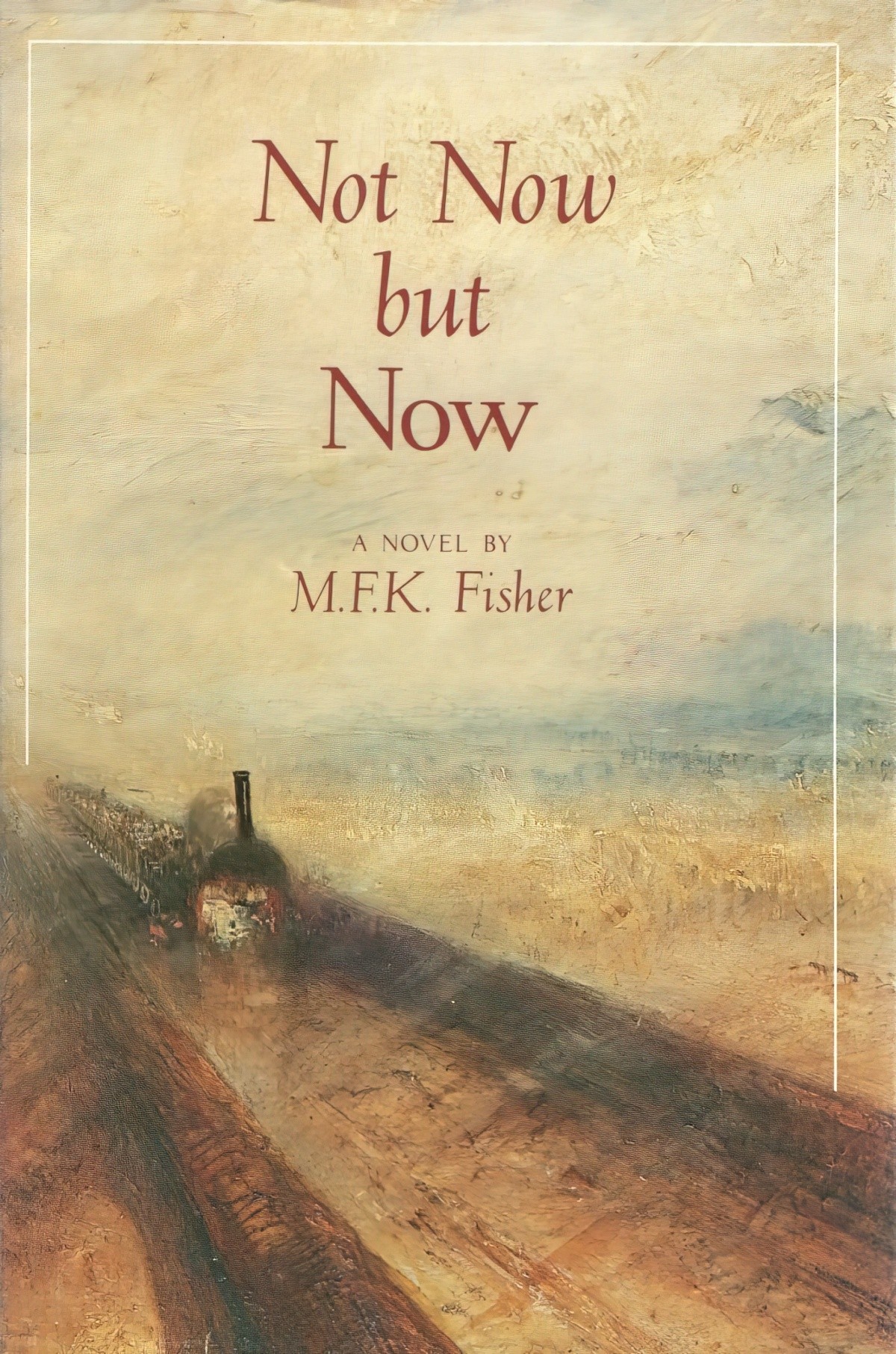

Not Now but Now by M.F.K. Fisher

Fisher was a food writer and this is her only novel. Told in the form of four novellas, a sensual, beautiful and egotistical woman called Jennie travels through time, living life to the fullest. Each novella features a different period: The 1930s, 1840s, 1920s and 1880s.

Jennie creates havoc in each time period then moves on.

POLICE PROCEDURAL

Police procedurals are the most popular subgenre of story worldwide. We have police procedurals such as The Wire, which has a dedicated and enthusiastic fanbase of those who like mimesis in their fiction.

How Police Procedurals Are Different From Real Police Work

POURQUOI TALES

Porquoi Tales offer folklore-type explanations for scientific phenomena or aspects of creation, for example, why the leopard has spots or how the stars came to be. The explanation is not scientifically true, and while this type of folktale is often serious, it can also have hilarious aspects integrated into the telling. Pronounced por-kwa, it means “why” in French. The Just So Stories by Rudyard Kipling are pourquoi tales.

A Picture Book Primer: Understanding and Using Picture Books by Denise I. Matulka

More Examples

- Why Mosquitoes Buzz in People’s Ears (1975) by Leo Dillo and Diane Dillon

- The Great Ball Game: A Muskogee Story (1994) by Susan L. Roth

- Why the Sun and the Moon Live In The Sky (1968) by Blair Lent

- Arrow to the Sun (1974) by Gerald McDermott

PRESTIGE TELEVISION (COMPLEX TELEVISION)

Complex TV: The Poetics of Contemporary Television

We are said to be in a golden age of TV. The best stories today are told on television screens in serialized forms. The Wire, Lost, Breaking Bad, The Sopranos are a few of the shows that have elevated the cache of television, introducing riskier forms of storytelling in a medium that has been typically formulaic and convention bound. Fans and critics alike celebrate them for innovation and television networks are filled programming with more and more of them. In Complex TV: The Poetics of Contemporary Television (NYU Press 2015), is film and television scholar Jason Mittell of Middlebury College offers a sustained analysis of the poetics of television narrative, focusing on how storytelling has changed in recent years and how viewers make sense of these innovations.

Complex television, Mittell says, is not a genre. It is a storytelling mode and set of associated production and reception practices that span a wide range of programs across an array of genres. Through close analyses of key programs, including The Wire, Lost, Veronica Mars, and Mad Mento name a four, the book traces the emergence of this narrative mode, focusing on issues such as viewer comprehension, transmedia storytelling, serial authorship, character change, and cultural evaluation. Developing a television-specific set of narrative theories, Complex TV argues that television is the most vital and important storytelling medium of our time. It is not that the best stories today are on the small screen. Rather, that the most sophisticated, freshest, and the most complex techniques for telling them are.

New Books Network

PSYCHOLOGICAL SUSPENSE

A psychological novel is a work of prose-fiction which places more than the usual amount of emphasis on interior characterisation, and on the motives, circumstances, and internal action which springs from, and develops, external action.

Wikipedia

The psychological novel is also called “psychological realism”.

Reality

The reality genre purports to document unscripted real-life situations, often starring unknown individuals (or up-and-coming celebrities) rather than professional actors. Reality television first emerged as a distinct genre in the early 1990s with shows such as The Real World, then achieved prominence in the early 2000s with the success of the series Survivor, Idols, and Big Brother. In fact, ‘reality’ is partly scripted, and even when not actually scripted, the scenes are edited to follow a satisfying narrative arc which will garner as many viewers as possible.

Right now I can picture my dad watching the Emmys & muttering “reality shouldn’t even be a category” & my mom telling him to shut up.

@sarahlapolla

I like stories. Reality TV, which we all know is not reality . . . I see greater truth in fiction than in that false reality . . . A criticism against television is you’re not using your imagination because it’s handing it all to you. Oh, really? How often do you keep thinking about this stuff later on, imagining where else the story might have gone or where it’s going? . . . You’re imagining the subsequent seasons of Firefly.

Experts Discuss the Psychology of Cult TV from The Mary Sue

TOTAL NOVEL, THE

A term which was first used to describe Latin American novels — works which are expected to speak for a country’s entire history, society, culture and imagination.

Australia has the film Australia, whose title suggests it’s doing the same thing.

True Story: What Reality TV Says About Us

Why is reality TV important? In True Story: What Reality TV Says About Us (FSG, 2022), Danielle J. Lindemann, an Associate Professor of Sociology at Lehigh University, uses a sociological lens to examine the meaning and role of reality TV in contemporary society. In doing so, the analysis demonstrates how reality TV reinforces often narrow and conservative stereotypes about families, gender, class, race, and sexuality. At the same time, the book shows how reality TV can offer representations for excluded communities and is not consumed uncritically by audiences, even as reality TV is reflective of broader social inequalities. Drawing on classical and contemporary sociological theories and frameworks, the book uses a huge range of examples, from some of the early reality TV classics, through the huge hits, to the niche and less well-known shows that both reflect and shape how life is shown on TV. The book is essential reading across the social sciences and arts and humanities, as well as for anyone interested in television!

interview at New Books Network

Reality TV: A Discussion with Olivia Stowell

In this episode of High Theory, Olivia Stowell speaks with Saronik about Reality TV.

She talks about the genesis of the genre in Candid Camera, An American Family, COPS and America’s Most Wanted, before the watershed moment of The Real World in the 1990s. She references the work of June Deery, and Pier Dominguez on the commercial realism and affective economies of reality tv, and Susan Douglass’s article “Jersey Shore: Ironic Viewing.” She reminds us that Reality TV dramatizes the life of the neoliberal subject under surveillance, and explicates our “trashy” desires.

Olivia Stowell is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Communication at the University of Michigan, where she studies the intersections of race, genre & narrative, food, and temporality in contemporary popular culture. Her scholarship has appeared or is forthcoming in Television & New Media and New Review of Film & Television, and her public writing has appeared in Post45 Contemporaries, Novel Dialogue, Avidly: A Channel of the L.A. Review of Books, and elsewhere.

interview at New Books Network

In this episode of High Theory, Olivia Stowell speaks with Saronik about Reality TV.

She talks about the genesis of the genre in Candid Camera, An American Family, COPS and America’s Most Wanted, before the watershed moment of The Real World in the 1990s. She references the work of June Deery, and Pier Dominguez on the commercial realism and affective economies of reality tv, and Susan Douglass’s article “Jersey Shore: Ironic Viewing.” She reminds us that Reality TV dramatizes the life of the neoliberal subject under surveillance, and explicates our “trashy” desires.

High Theory Podcast

Realism

John Stephens has said that the distinction between fantasy and realism is ‘the single most important generic distinction in children’s fiction‘. On the other hand, children’s literature academic Maria Nikolajeva doesn’t make that particular distinction, treating ‘all children’s literature as essentially “mythic” or at least non-mimetic‘. [Non-mimetic means not even trying to emulate reality.]

Rural Gothic

The Rural Gothic constitutes a specifically American subgenre of the Gothic, one shaped by “the powerful historical and cultural legacy that sprang from the first encounters between European settlers, the North American landscape, and its original inhabitants.

Jonathan Newell, quoting Bernice Murphy

A good example of the rural Gothic is “The Picture In The House” by H.P. Lovecraft (1921).

ROMANCE

Perhaps because romance readers are such keen readers, oftentimes consuming more than one romance story per week, the romance genre has developed an extensive set of subgenres within it.

Romance stories are about two lovers coming together after numerous trials.

A general rule of romance: It ends happily. If a ‘romance’ story has a tragic ending, and it’s not a subgenre like ‘tragic romance,’ readers will feel cheated.

SCIENCE FICTION

Also known as futuristic fiction (especially if there’s less emphasis on the science).

Humans in sci-fi seem greatly reduced because science fiction is about the evolution of humankind. Sci-fi authors convince us that something unusual could happen because their stories are grounded in scientific principles or in technical possibility.

Short Story

Short stories are a description of length and are not a genre per se. That said, there are two main types of short story: lyrical and genre.

SKETCH COMEDY

“Sketch comedy – more than any other television genre – lays bare the process of identity formation, pokes fun at its contradictions, and invites us to debate its terms.” In Sketch Comedy: Identity, Reflexivity, and American Television (Indiana University Press, 2019), author Nick Marx makes this argument and goes on to systematically prove it through a series of case studies dating from the earliest days of network television through to our post-network era. While sketch is an understudied form of television expression and a genre that rarely garners full-throated network support, it remains one of the most playful, political, and experimental kinds of programming in U.S. television. Close readings of the on-screen representations and off-screen politics of shows including Saturday Night Live, The State, and Key & Peele drive home how vital it is that television scholars and fans recognize the power of sketch in forming what we watch, what we think, and what we believe.

In this conversation, Nick Marx discusses this book, his first solo-authored monograph, in conjunction with his prior publications, defines his term “reflexivity flexibility,” gives it up for Mr. Show with Bob and David, and gives it to Pete Davidson.

New Books Network

SERIAL KILLER THRILLER

About police officers doing their jobs (Silence of the Lambs)

SLIPSTREAM

Slipstream is a kind of fantastic or non-realistic fiction that crosses conventional genre boundaries between science fiction, fantasy, and literary fiction. It is a highly metaphorical type of story.

The term was coined in the 1980s by Richard Dorsett. These stories are Postmodern.

A uniting feature of slipstream stories: Some element of the not-real e.g. Surrealism.

SPORT

The Sports Film: Games People Play

One of the most enduring film genres is the sports movie. From the earliest attempts at narrative motion pictures to the present day, movies devoted to athletic competition are both popular and lasting. In The Sports Film: Games People Play (Wallflower Press, 2014), Bruce Babington presents an historical overview of the genre. He also details four specific films that cover a wide range of sports and national cinema. Drawing upon a large body of knowledge as a writer and professor of film, Babington discusses the importance of the sports film, as well as why it remains so popular.

New Books Network

Hollywood Sports Movies and the American Dream

Through the heart of Hollywood cinema runs a surprising current of progressive politics. Sports movies, a genre that has flourished since the mid-seventies, evoke the American dream and represent the nation to itself. Once considered mere credos for Reaganism, on closer view, movies from Rocky (1976) to Ali (2001) dream of democratic participation and recognition more than individual success. In every case, off-field relationships take precedence over on-field competition.

Arranged chronologically, Hollywood Sports Movies and the American Dream (Oxford UP, 2022) tells the story of multiculturalism’s gradual adoption. The mainstream’s first minority heroes are paradoxically white ethnic, rural, working-class men, exemplified by Rocky, Slap Shot (1977) and The Natural (1984); Black, brown, and women characters follow in White Men Can’t Jump (1992), A League of Their Own (1992), and Ali. But despite their insistence on community and diversity these popular dramas show limited faith in civic institutions. Hannah Arendt, Jeffrey Alexander, and others inform original analysis and commentary on the political significance of popular culture. Reading these familiar movies from another angle paints a fresh picture of how the United States has imagined democracy since its bicentennial.

In this conversation with host Annie Berke, Dr. Grant Wiedenfeld explains his personal and familial connections to the book’s subject matter, discusses why Hollywood sports films don’t always have (or need) a “happy ending,” and explains how the genre functions as a “civic screen” for the American public in the decades following the Vietnam War.

Grant Wiedenfeld earned a PhD from Yale University in Comparative Literature and Film & Media Studies. He taught courses on sports and cinema in Yale’s English Department and Film Studies Program before being hired at Sam Houston State University, where he is currently Associate Professor of Media and Culture. Previous publications include studies of Gustave Flaubert, D.W. Griffith, and André Bazin.

at New Books Network

Keepers of the Flame: NFL Films and the Rise of Sports Media

Last weekend was the NFL Draft, the annual event when teams select college players who have shown the talent to advance to the professional ranks. Staged at New York’s Radio City Music Hall, broadcast live on two cable networks, and surrounded by ceaseless media attention and analysis, the Draft is the spring anchor-point of the NFL as a year-round attraction. Decades ago, the Draft was nothing more than a business meeting. Yet even then the NFL was taking steps to establish itself as a year-round sports league. This came not on cable television, but in church basements and community meeting halls. The menfolk would gather after banquets or father-son dinners and watch films of football–real films, supplied in metal cans and spooled into projectors. They might watch highlights of the last Super Bowl or their local team’s season, a documentary about the great players of the recent past, or a compilation of on-field blunders by players, coaches, and referees. Even though it was the dead of winter, the audience would come away from the screening eager for football. These were the productions of NFL Films. Captured by motion picture cameras, set to orchestral scores, and narrated by the dulcet baritone of John Facenda, these films presented football as high art: a contest of mythic heroes and the embodiment of American virtue. Travis Vogan gained full access to the NFL Archives for his study of the filmmaking arm of the National Football League: Keepers of the Flame: NFL Films and the Rise of Sports Media (University of Illinois Press, 2014). Starting as a father-and-son operation, NFL Films became an integral part of the rise of professional football in the US. Even more than that, Travis argues, its productions have shaped the way that all sports are broadcast and promoted. As a side note: Travis will be one of the writers for the new online journal The Allrounder, along with several scholars and journalists you’ve heard on past episodes of the podcast. The Allrounder has the same aim as New Books in Sports, to get people thinking in new ways about the sports they follow by making available in-depth research and thoughtful writing.

New Books Network

Tall Tales

Tall tales are an historically masculine form of oral storytelling in which the aim is to string the listener along, sometimes with the aim of tricking them into thinking you’re telling a true story, until something completely unbelievable happens.

THRILLER

The main character will be a low mimetic hero (using Northrop Frye’s terminology), meaning an ordinary person. This ordinary person is thrown into extraordinary circumstances. Their life is at risk.

Unlike detective stories, thrillers don’t need a vast cast of characters (suspects) in order to work.

TRADITIONAL LITERATURE

Myth, folktale, fairytale, fables, religious stories and so on. There are no official authors.

Transgression Comedy

Masks In Storytelling (about transgression comedies and transgression thrillers)

Transgression Thriller

TRAUMA NOVEL

Trauma…refers to a person’s emotional response to an overwhelming event that disrupts previous ideas of an individual’s sense of self and the standards by which one evaluates society.

The term “trauma novel” refers to a work of fiction that conveys profound loss or intense fear on individual or collective levels.

A defining feature of the trauma novel is the transformation of the self ignited by an external, often terrifying experience, which illuminates the process of coming to terms with the dynamics of memory that inform the new perceptions of the self and world.

The external event that elicits an extreme response from the protagonist is not necessarily bound to a collective human or natural disaster such as war or tsunamis.

The event may include, for example, the intimately personal experience of female sexual violence, such as found in Dorothy Allison’s Bastard Out of Carolina and Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, or the unexpected death of a loved one, as found in Edward Abbey’s Black Sun.

Trends in Literary Trauma Theory, an abstract by Michelle Balaey

Urban Fantasy

“It sometimes seems to me that the main difference between urban fantasy and horror is simply a matter of competency. Urban fantasy characters generally take vampires and zombies in stride and react as competently as the reader would like to think they would do in similar straits.” (Greg Cox)

URBAN LEGEND

‘Urban’ legend is a misnomer, because they are frequently set in the country or bush. Another term (which hasn’t really taken off): FOAFs. This stands for ‘Friend-of-a-friend story’, meaning the person telling it supposedly heard of it through the grapevine. ‘Urban legend’ is shorthand for a wacky gossip, often supernatural. Some of these stories are designed to frighten, others to entertain.

Urban legends frequently fall under the umbrella of tall tales, because the person hearing it is supposed to believe it’s true.

In the 1960s, folklorists were calling these tales ‘modern’, ‘urban’ or ‘contemporary’ legends to distinguish them from more traditional stories of antiquity. ‘Urban’ seems to have stuck the best.

However, like any legend or myth, these ‘modern’ stories aren’t new. They each have a deep, complicated ancestry. Folklorists can trace many back to the Medieval period.

Uncanny

The uncanny is a term originating from the German das unheimlich, and comes from Freud, but when people use it today, they may not be hewing closely to Freud’s definition.

Freud described the uncanny as “that class of the terrifying which leads back to something long known to us, once very familiar”. The uncanny represents the liminal space between what is capable of being understood as outward in the world and what is hidden. Though we may get a sense of the familiarity, its true connection to the past is never quite in our reach. Through repression or burying, the uncanny is never able to be fully comprehended— it can, however, be sensed or felt.

The word ‘unheimlich’ is the opposite of ‘heimlich’, which has various definitions, all related to ‘the home’ e.g. ‘belonging to the home’. The home is (hopefully) where we experience peaceful pleasure and security.

The uncanny is experienced upon encountering something that is at once both strange and familiar. Tzvetan Todorov (in his book The Fantastic: A Structural Approach to a Literary Genre) argues that the uncanny is characterized by a character’s response – often fear – towards something seemingly inexplicable, or impossible. to Todorov, the uncanny is the supernatural explained. Some scholars (e.g. Murray Leeder) argues that Todorov used the word ‘uncanny’ in a slightly different way from how Freud used it.

Because ‘heimlich’ comes from ‘home’, when storytellers defamiliarise the home and make us feel uncomfortable about our most intimate spaces, many uncanny stories focus on the family home. Shirley Jackson was a master of this form.

Vampire romance

A subgenre of romance which is about intimacy rather than a disconnection between human and nonhuman. Obsession by Lori Herter in 1991 was the first vampire novel to be marketed as a romance rather than shelved with horror or fantasy.

VAUDEVILLE

A Revolution in Three Acts: The Radical Vaudeville of Bert Williams, Eva Tanguay, and Julian Eltinge

Too often, vaudeville is seen from the perspective of its decline: it is the corny, messy art form that predated the book musical, or that gave us Chaplin, Keaton, and the Marx Brothers. Rarely is it seen as the populist avant-garde form it was at its height. David Hajdu and John Carey’s graphic history, A Revolution in Three Acts: The Radical Vaudeville of Bert Williams, Eva Tanguay, and Julian Eltinge (Columbia University Press, 2021), corrects this misconception, giving us illustrated biographies of three of the genre’s most outré and successful stars.

Eva Tanguay challenged contemporary gender roles through her outrageous behavior and sexually suggestive songs.

Julian Eltinge also subverted gendered expectations of femininity by performing them to the hilt — but as a man.

And Bert Williams, a black man who performed in black face, tried to use his fame to soften the hard edges of Jim Crow bigotry but eventually became exhausted by the racism he encountered within the entertainment industry.

These three performers truly were revolutionary, and their stories should be known to any theatre fan or historian.

New Books Network

VIDEO GAME

Felix Schniz’s book Genre and Video Game: Introducing an Impossible Taxonomy (Genre und Videospiel: Einführung in eine unmögliche Taxonomie) explains video game genres as multidimensional and deeply mutable concepts enacted by the interplay of three dimensions: In addition to the hybrid approaches of genre theory, fiction genre and game genre, there are also social components that shape the gaming experience.

Working with video games (and working with their genres) turns out to be working with an objet ambigu: an intangible object of art whose potential is revealed and developed, again and again, in the process of interacting with the user.

New Books Network

War Stories

War-time stories are sometimes treated as a separate genre, in British children’s fiction especially, but Nikolajeva does not consider them separate.

The Philosophy of War Films

Films that feature war as a theme have been made almost since the beginning of the industry. In The Philosophy of War Films (University Press of Kentucky, 2018), part of the “Philosophy of Popular Culture Series,” David LaRocca brings together a number of prominent authors to discuss the genre as a way to consider how war films have impacted us. The contributors explore a variety of topics, including the aesthetics of war as portrayed on-screen, the effect war has on personal identity, and the ethical problems presented by war.

New Books Network

Real War vs. Reel War: Veterans, Hollywood, and WWII

In hew new book Real War vs. Reel War: Veterans, Hollywood, and WWII (Rowman and Littlefield, 2015), Suzanne Broderick shares how she discussed a number of World War II films with veterans and others who experienced the conflict first hand.

New Books Network

Western

A genre set primarily in the latter half of the 19th and early 20th century in the Western United States, the “Old West”. Classic Westerns are a celebration of American expansionism. Today, anti-Westerns are known simply as Westerns.

WOMAN IN JEOPARDY THRILLER

A thriller told from the point of view of a vulnerable woman who must find her way out of a life and death situation

Women’s Fiction

A marketing term rather than a genre. When marketing departments decide a book will likely be purchased mainly by women, they call it women’s fiction.

Young Adult

Is it a “genre” or a “category”?

I think it’s a lack of exposure to contemporary YA lit that makes adults refer to it as a “genre.” Much of the time when people say “the YA lit genre,” what they really mean iscategory rather than genre, and that’s fine. However, I recently attended a talk by an author who had been writing adult genre fiction and was working on her first YA novel, and she kept referring to the characteristics of the YA genre, as if all YA books were somehow fundamentally the same.

In the library with the leadpipe

FURTHER READING

Genre Theory — continued from Michael Rosen.

The Labryrinth of Genre is a web app which helps you to find subgenres of a genre.

Why writers should leave book-genre debates to the marketing department

Header illustration: City of the future c 1900