I enjoy stories about characters with wild imaginations, and that may partly explain why I love children’s books. From Where The Wild Things Are to highly symbolic fairytales to post-modern off-kilter realities, children’s literature is full of dreamscapes and fantastic journeys. But stories of imaginative power don’t end with childhood — there are many examples from general fiction of characters who create rich fantasies.

We all have three lives after all — our public life, our private life and our secret life. We rarely get a glimpse into other people’s secret lives. We may occasionally get bits and pieces, from friends and from family, but fiction offers the most in-depth explorations about how others might think. Our fantasy world is part of our secret world. We rarely share it with others.

That’s if we even have such a world. I have learned over the years that some people do and some people have nothing as organised and detailed as a ‘world’, but we are all creatures with immense imaginative capacity.

Most people spend between 30 and 47 percent of their waking hours spacing out, drifting off, lost in thought, woolgathering…

Scientific American

Why do we want to have alternative worlds? It’s a way of making progress. You have to imagine something before you do it.

Joan Aiken

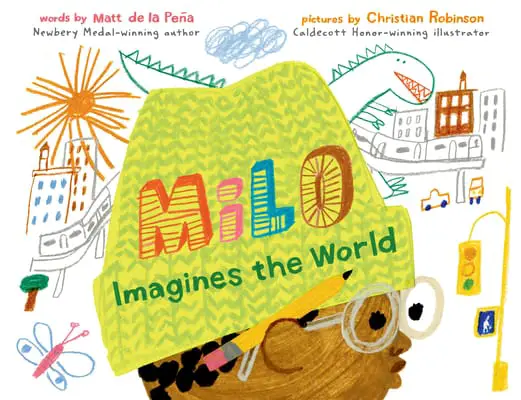

Milo is on a long subway ride with his older sister. To pass the time, he studies the faces around him and makes pictures of their lives. There’s the whiskered man with the crossword puzzle; Milo imagines him playing solitaire in a cluttered apartment full of pets. There’s the wedding-dressed woman with a little dog peeking out of her handbag; Milo imagines her in a grand cathedral ceremony. And then there’s the boy in the suit with the bright white sneakers; Milo imagines him arriving home to a castle with a drawbridge and a butler. But when the boy in the suit gets off on the same stop as Milo–walking the same path, going to the exact same place–Milo realizes that you can’t really know anyone just by looking at them.

CONSCIOUS DEPARTURE FROM CONSENSUS REALITY (COMPOS MENTIS)

- No imagination whatsoever — a computer

- The imaginative power which evolved as a huge advantage — the ability to look at a situation and imagine what might go wrong: worry. Also the ability to plan ahead, by imagining the future. Other apes can do this.

- The ability to build imaginative worlds based on stories told by others.

- A gradual expansion of the imaginative worlds of others, leading up to creating one’s own fan-fic or imagining oneself as Super-man.

- Fangirl by Rainbow Rowell

- Children’s stories in which the characters dress up in costume and ‘fight crime’ or similar

- Fantasies become self-generated. The imaginer comes up with original creations, or significantly modifies the creations of others.

- The short story “What Is Remembered” by Alice Munro details the quiet inner world of an older woman — an imagination furnished by one main incident from her youth.

- Munro’s female characters often develop imaginative tricks to get on with their lot in lives, whether it’s to deal with loneliness (imagining oneself on “Cortes Island” or to cope with a missing or estranged family member.

- The imaginer denies unpleasant truths by making up alternative theories or by nurturing their own wilful ignorance.

- In Helen Simpson’s “In-Flight Entertainment“, Alan won’t hear anything about climate change from the retired scientist sitting opposite, despite living in it.

- “Her First Ball” by Katherine Mansfield stars Leila, who decides to ignore the old man telling her that she will one day be old.

- The imaginer creates an expansive, detailed imaginative world or worlds.

- The Secret Life of Walter Mitty — a classic short story by James Thurber. The descriptor ‘Walter Mitty’ is now used to refer to person (usually a man) so caught up in his imagination that he no longer seems to feel the need to work hard to elevate his status in his real life. The modern Walter Mitty might be a guy who gets so much reward from the fantasy World of Warcraft that he quits his job to play it, eschewing the dominant culture’s view of how a man should properly live.

- “Paul’s Case” by Willa Catha is another short story example from America.

- “Miss Brill” by Katherine Mansfield is another story about a person with a small life, imagining something different.

- The character of Bertha in Mansfield’s “At The Bay” series is a bit of a Walter Mitty character. Unmarried, unfulfilled, she imagines all sorts of scenarios with herself as a swept away romantic heroine.

- But in Mansfield’s “The Escape“, it’s the husband rather than the wife who uses a fantasy world to escape from an unsatisfying married life.

- My Summer In Love, Emily Blunt’s first film, is about two young women — Tamsin draws the other, more naive girl unwittingly into her re-imagined reality.

- Similar to My Summer In Love is Peter Jackson’s Beautiful Creatures, a New Zealand film set in my hometown of Christchurch, based on the true story of two teenage girls who murdered one of their mothers.

- The most detailed of these fantasy worlds are known as paracosms. This is a term most often associated with the Bronte sisters, who invented the rich imaginative country of Gondal. The imaginer dips into these worlds often, probably every day, multiple times per day. This is a power required of novelists and screenwriters, but also the creators of poems and short stories.

- Bridge to Terabithia — a middle grade novel by Katherine Paterson about two children who invent a fantasy world across the river from their home.

- Any portal fantasy could be read as the paracosm of the main characters. I consider The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe the collaborative fantasy of Christian-raised children bored in a big house because they’ve been evicted from London during the otherwise traumatic WW2.

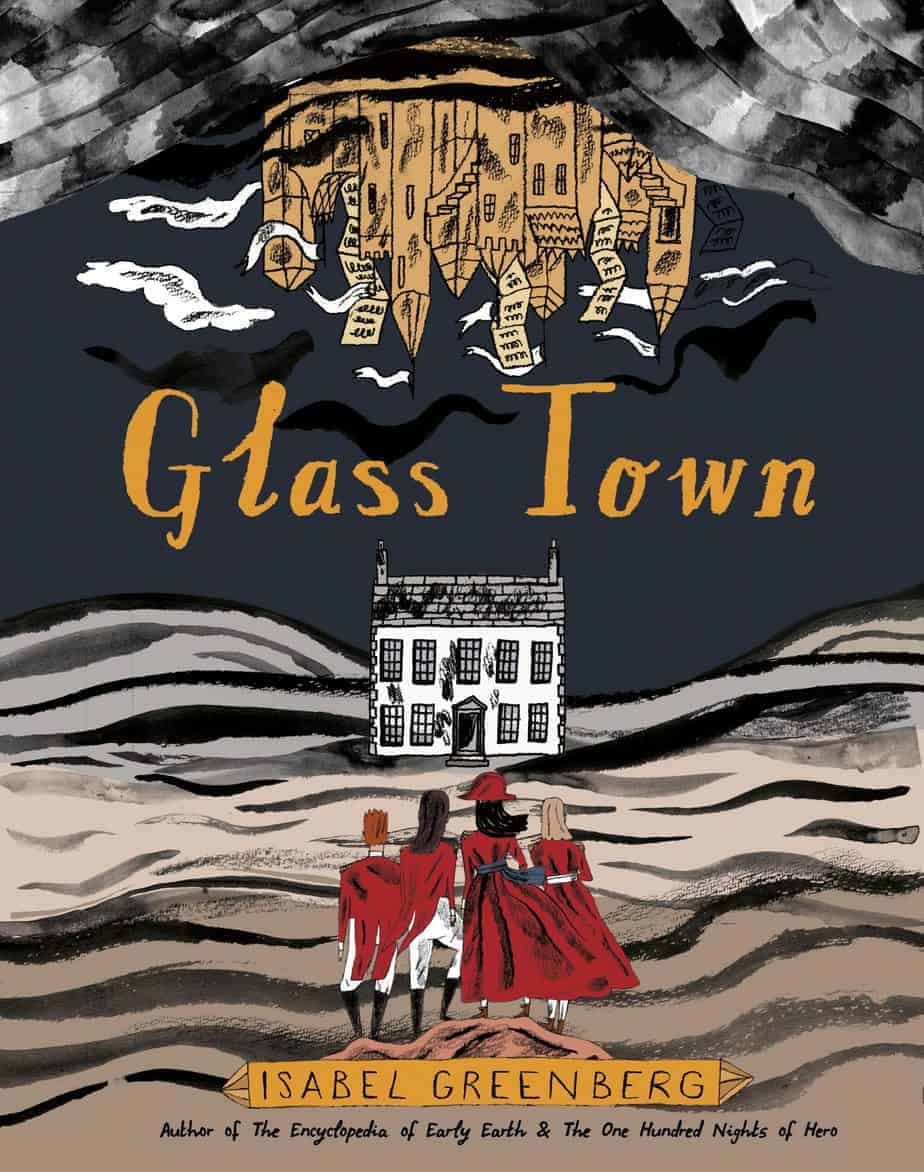

A graphic novel about the Brontë siblings, and the strange and marvelous imaginary worlds they invented during their childhood

Glass Town is an original graphic novel by Isabel Greenberg that encompasses the eccentric childhoods of the four Brontë children—Charlotte, Branwell, Emily, and Anne. The story begins in 1825, with the deaths of Maria and Elizabeth, the eldest siblings. It is in response to this loss that the four remaining Brontë children set pen to paper and created the fictional world that became known as Glass Town. This world and its cast of characters would come to be the Brontës’ escape from the realities of their lives. Within Glass Town the siblings experienced love, friendship, war, triumph, and heartbreak. Through a combination of quotes from the stories originally penned by the Brontës, biographical information about them, and Greenberg’s vivid comic book illustrations, readers will find themselves enraptured by this fascinating imaginary world.

Then we encounter the soft line of sanity, in which the imaginer may lose touch of the distinction between imagination and reality, starting with minor distortions, then mixed reality (a term I’m borrowing from Paul Mulgram’s Reality-Virtuality Continuum).

Another word for ‘consensus reality’ might be ‘veridical reality’. Veridical means ‘coinciding with reality’ (whatever reality might be).

UNCONSCIOUS DEPARTURE FROM CONSENSUS REALITY (NON COMPOS MENTIS)

- False Memory — separate from the unconscious departures below in that not everyone experiences psychosis/dementia and so on, but each and every one of us has a faulty memory.

Helen Hayward makes a distinction between ‘memories’ and ‘reminiscences’:

When it comes to thinking about early loved ones often it is our reminiscences, more than our memories, that spring to mind. […] A reminiscence is an overloaded memory, on to which feelings from another memory — now recalls a past event, a reminiscent relives it. Because a reminiscence contains fantasies which have escaped the ego’s notice — unlike a memory which the ego is able to repress — it can remain in consciousness. If however these feelings do emerge, and the fantasy is unveiled, the feelings are likely to be spontaneously repressed.

Helen Hayward, Never Marry A Girl With A Dead Father

Separately we have the departures borne of more serious malfunctions of mind:

- Psychosis (including hallucinations, delusions, delirium)

- Dissociative disorders (dissociative amnesia, dissociative identity disorders, depersonalisation disorders)

- On TV Tropes there are many examples of Identity Amnesia as it presents in fiction, which is quite different from how it presents in reality.

- United States of Tara

- “Powers” by Alice Munro is a mish-mash of how various factors affect our hold on reality. The story includes epileptic fits, possibly electric shock treatment and definitely dementia.

- “Dissociative Identity Disorder is by far one of the least understood mental illnesses out there. It is enshrouded in misinformation, outdated coursework (for students and practicing clinicians alike), and a seemingly unending barrage of defamation attempts.” — Beauty After Bruises

- Folie a deux — a mental disorder (not a mental illness) that two people share and experience at the same time.

- Possibly Heavenly Creatures, in which two teenage girls thought it was a good idea to kill a mother.

- In fiction, a related trope is called Infectious Insanity.

- Dementia

- “The Bear Came Over The Mountain” by Alice Munro is told from the perspective of the dementia patient’s husband but we get some insight into her loosening grip on reality.

At the heart of this classic, seminal book is Julian Jaynes’s still-controversial thesis that human consciousness did not begin far back in animal evolution but instead is a learned process that came about only three thousand years ago and is still developing. The implications of this revolutionary scientific paradigm extend into virtually every aspect of our psychology, our history and culture, our religion — and indeed our future.

Bicameral: having two chambers

THE IDEOLOGY OF IMAGINATIVE POWER

The corpus of stories about fantasists leads us to the same, culturally-agreed conclusion: Imagination is fine so long as you:

- Maintain a clear division between fantasy and reality;

- Don’t engage others in your own fantasies without their full knowledge and consent.

We could add an axis based on positive/negative valence. To what extent do a character’s fantasies (etc.) have a positive/negative impact upon their life?

Well, it can go either way. Psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud knew that reminiscences can indeed lead to unhappiness. His psychoanalysis aimed to lighten this load.

Every memory you have ever had is chock-full of errors. I would even go as far as saying that memory is largely an illusion.

What Experts Wish You Knew About False Memories from Scientific American

IMAGINATION AND LOVE

The world of Eros is the world of the imagination.

Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben wrote in his work Stanze (1977) that during the Middle Ages, love was seen as a labour of the imagination. In order to fall in love, it was thought that you had to fall in love with an image of another person, recreated from memory. In this way, both memory and love both rely upon one’s imaginative powers. The lover is in love with the (self-generated) image.

THE GENDERED NATURE OF FICTIONAL FANTASISTS

I’ve done no broad study of this, but of the stories I’ve encountered, there seems to be some gendered differences.

- Both male and female characters are often revealed in fiction to harbour fantasies of various kinds.

- But if there are victims of these fantasies, the victim is more often a woman, regardless of gender.

- Male characters seem particularly drawn to the romantic hero — super heroes and war heroes. They imagine themselves saving the day, especially saving girls and women.

- The male character in “I’m A Fool” displays strong imaginative powers when he spins a story about being a completely different person… to try and snag a girl. Again, this is borne of wanting more power in real life.

- But sometimes male characters imagine themselves as baddies, like the main character in “The Housebreaker of Shady Hill” by John Cheever. To be a bad guy, breaking the rules, is its own form of social capital.

- Male characters often fancy themselves younger and try to regain their youth by sexual involvement with a girl, sometimes underage as in Lolita’s Humbert Humbert, or the main character of Thomas Keneally’s short story, “Blackberries“, or of Robert Drewe’s “A View of Mount Warning” or any number of similar tales which centre a man’s sexual desires.

- For female fantasists, there is often a witch overtone. This is definitely the case for Tamsin in My Summer of Love. She draws in her victim with deceit — they dress up and drink ‘potions’ and go into the wilderness. Their final big struggle takes place in a river, with one almost drowning the other. Likewise, the true story behind Heavenly Creatures captured public imagination because two teenage girls seemed caught up in a folie a deux fantasy leading to someone’s death — again, another woman. We are, as a culture, scared of the erotic powers of young women and we imagine that when two young women get together their evil powers are doubled. “Ernestine and Kit” by Kevin Barry is also about the dangerous power of contemporary witches.

- Fictional girls and woman seem more likely to be the creators/initiators of vast, collaborative imaginative worlds. In Bridge to Terabithia it is the girl, Leslie, who comes up with the concept. The boy goes along with it. It’s Lucy who discovers the wardrobe portal to Narnia. In “The People Across The Canyon”, the highly imaginative child just happens to be a girl.

What do you think? Is there a gendered difference in the depiction of fictional fantasists?

TYPES OF DAYDREAMING

An article in Scientific American traces the development of research on the art of daydreaming.

Daydreaming is broken into 3 types:

1. Positive-Constructive Daydreaming

representing playful, wishful and constructive imagery

This not only sounds lovely; it sounds beneficial to individuals and society. Surely it’s by engaging in this sort of daydreaming that we come up with our best ideas.

2. Guilty-Dysphoric Daydreaming

representing obsessive, anguished fantasies

This sounds like a sort of post-traumatic response, or ‘stewing’, in everyday parlance. Some people seem to do this quite a lot, turning minor arguments into huge ones, but only in their own minds. For obvious reasons we should try not to let our minds engage in this sort of daydreaming.

3. Poor Attentional Control

representing the inability to concentrate on ongoing thought or external tasks

I now imagine an old-fashioned classroom — the kind with wooden floors and chair legs scraping, and chalk screeching down blackboards, led by a cane-toting teacher scalding Jimmy for staring out of the window. That’s the classic picture of the childlike and carefree pupil of yesteryear, constrained and reined in by the school system until he is old enough to be put to work in the mines.

This kind of daydreaming can stop you from getting things done, sure.

“When a woman is frozen of feeling, when she can no longer feel herself, when her blood, her passion, no longer reach the extremities of her psyche, when she is desperate; then a fantasy life is far more pleasurable than anything else she can set her sights upon. Her little match lights, because they have no wood to burn, instead burn up the psyche as though it were a big dry log. The psyche begins to play tricks on itself; it lives now in the fantasy fire of all yearning fulfilled. This kind of fantasizing is like a lie: If you tell it often enough, you begin to believe it.”

Clarissa Pinkola Estés, Women Who Run With the Wolves: Myths and Stories of the Wild Woman Archetype

FURTHER READING

Young children, of nursery school and kindergarten age, also practice emotional regulation in their make-believe, fantasy play. They play at emotion-provoking themes, including themes that induce fear, anger, and sadness. One person who has documented this, through observations in kindergartens, is the German researcher Gisela Wegener-Spöhring. For example, she described one play scene in which two little girls pretended that they were sisters whose father and mother had died and who were abandoned alone in the woods, with bears and other wild animals around. To deal with both their grief and fear, they held each other close and spoke intimately, and they built a cave to protect themselves and figured out what weapons they would use if a bear entered the cave.

Psychology Today

As neuroscientists study the idle brain, some believe they are exploring a central mystery in human psychology: where and how our concept of “self” is created, maintained, altered and renewed. After all, though our minds may wander when in this mode, they rarely wander far from ourselves, as Mrazek’s mealtime introspection makes plain.

An idle brain may be the self’s workshop from The Chicago Tribune

Hearing voices is also a pretty normal thing that happens to people and you don’t have to have a diagnosable mental illness to hear them. This, too, can be attributed to ghosts, or paranormal activity:

Anthropologist Tanya Luhrmann, who has studied voice hearing in psychiatric and religious contexts, has written that “historical and cultural conditions … affect significantly the way mental anguish is internally experienced and socially expressed.” Noting that there is no question psychiatric distress and schizophrenia are “real” phenomena that call for treatment, Luhrmann adds that “the way a culture interprets symptoms may affect an ill person’s prognosis.” Every psychiatrist I spoke to shared the belief that unusual behaviour should only enter into the realm of diagnosis when it causes suffering.

Joseph Frankel, The Atlantic

SEE ALSO

The Destructive Influence of Imaginary Peers from Farnam Street

The Magic of Metaphor: What Children’s Minds Teach Us about the Evolution of the Imagination from Brain Pickings

Creating Hallucinations Without Drugs Is Surprisingly Easy by BEC CREW at Science Alerts

Explaining Imagination

How do we think about situations and things do not exist but might, engage in pretense and fiction, and create new works of art? These are central cases in which we’re using our imaginations, but what is imagination, and how should it be explained? In Explaining Imagination (Oxford University Press, 2020), Peter Langland-Hassan distinguishes using mental imagery to think about things and thinking about imaginary things, and proceeds to give a reductive account of both. On his view, imagining isn’t a sui generis mental state, as the received view holds. Instead, it can be reduced to more basic states, in particular belief, desire, and intention. Langland-Hassan, who is associate professor of philosophy at the University of Cincinnati, uses his account to explain the central cases of imagination, defends his view against objections, and considers how recent advances in Deep Learning might help explain the creative process.

New Books Network

Gabby’s world is filled with daydreams. However, what began as an escape from her parents’ arguments has now taken over her life. But with the help of a new teacher, Gabby the dreamer might just become Gabby the writer, and words that carried her away might allow her to soar. Written in vivid, accessible poems, this remarkable verse novel is a celebration of imagination, of friendship, of one girl’s indomitable spirit, and of a teacher’s ability to reach out and change a life.