Once upon a time clowns were an un-ironic take on the jester archetype. Storytellers could make use of clowns to lighten a mood. Shakespeare did it.

Toon. A comic relief character generally intended to be recognized as such — Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are toons (most of Shakespeare’s comic relief characters are toons). Toons have a limited place in fiction; an excess of them can render an otherwise serious work trivial. (CSFW: David Smith)

A Glossary of Terms Useful In Critiquing Science Fiction

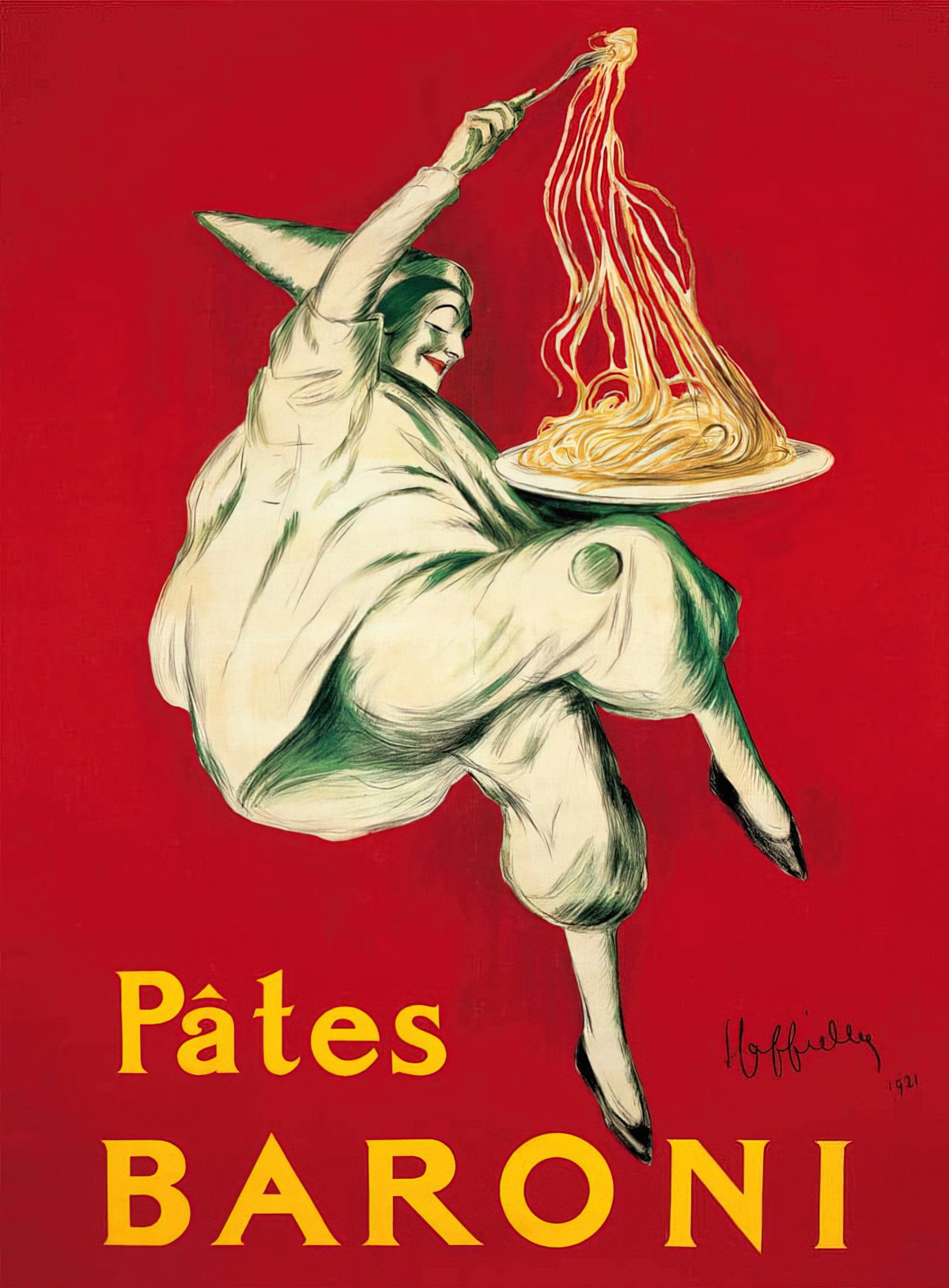

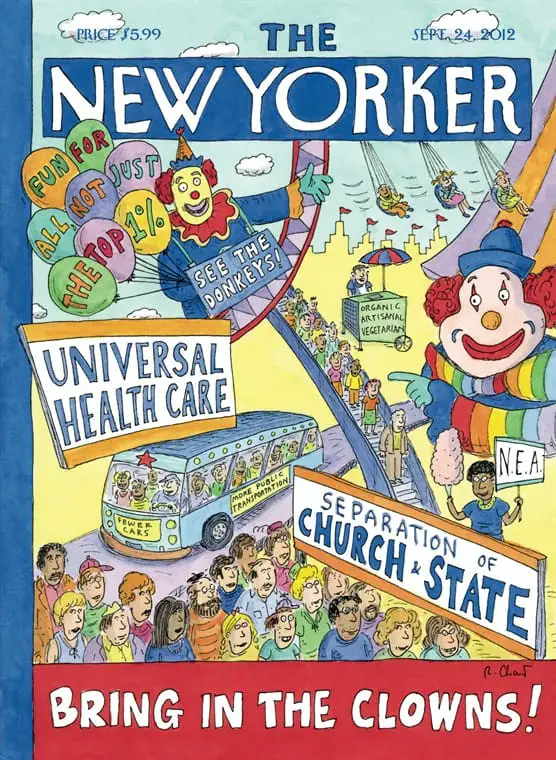

BRINGING IN THE CLOWNS

When Shakespeare figured the audience had had enough of the heavy stuff, he’d let up a little, bring in a clown or a foolish innkeeper or something like that, before he’d become serious again. And trips to other planets, science fiction of an obviously kidding sort, is equivalent to bringing in the clowns every so often to lighten things up.

Kurt Vonnegut

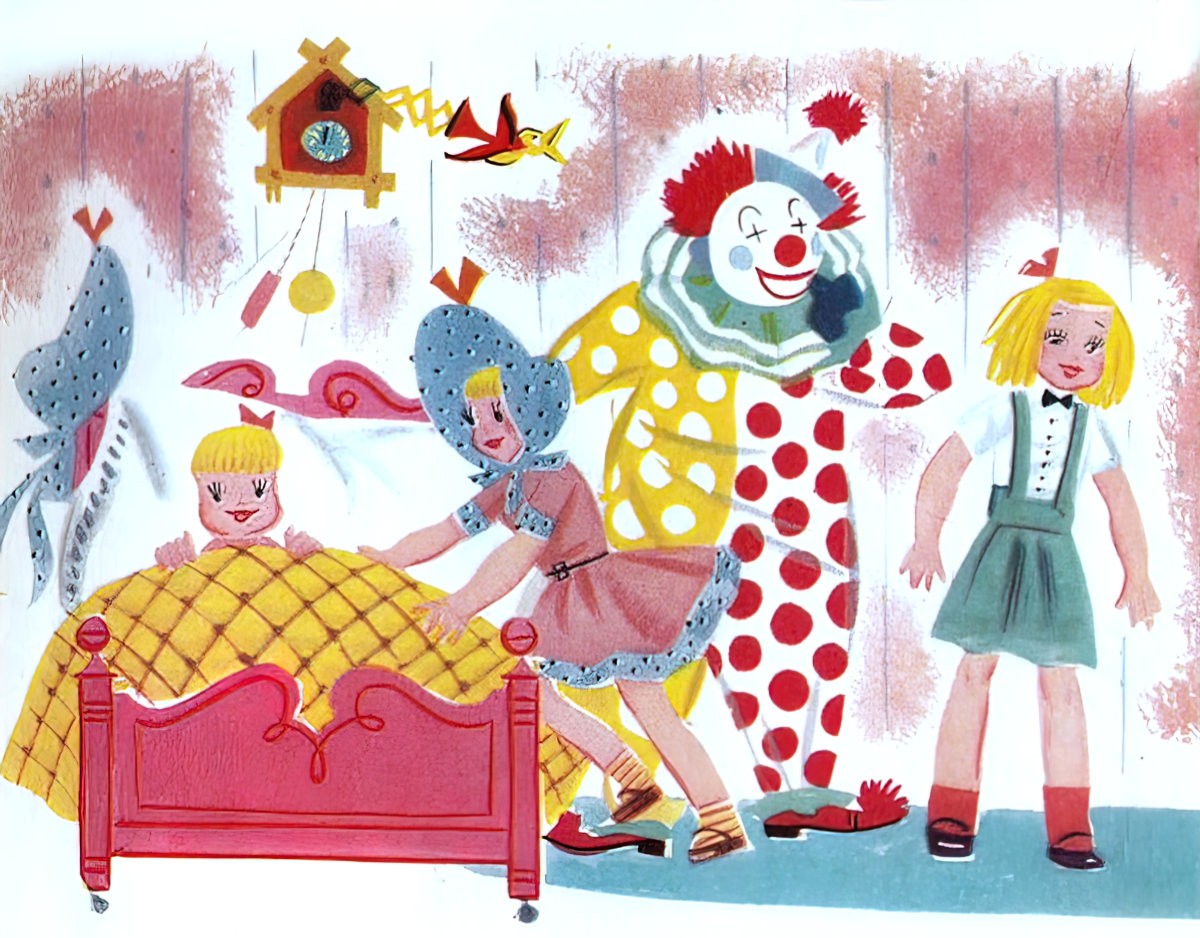

Carlos Marchiori Illustrations for Edith Fowke – Sally Go Round The Sun 300 Songs, Rhymes and Games of Canadian Children (1969)

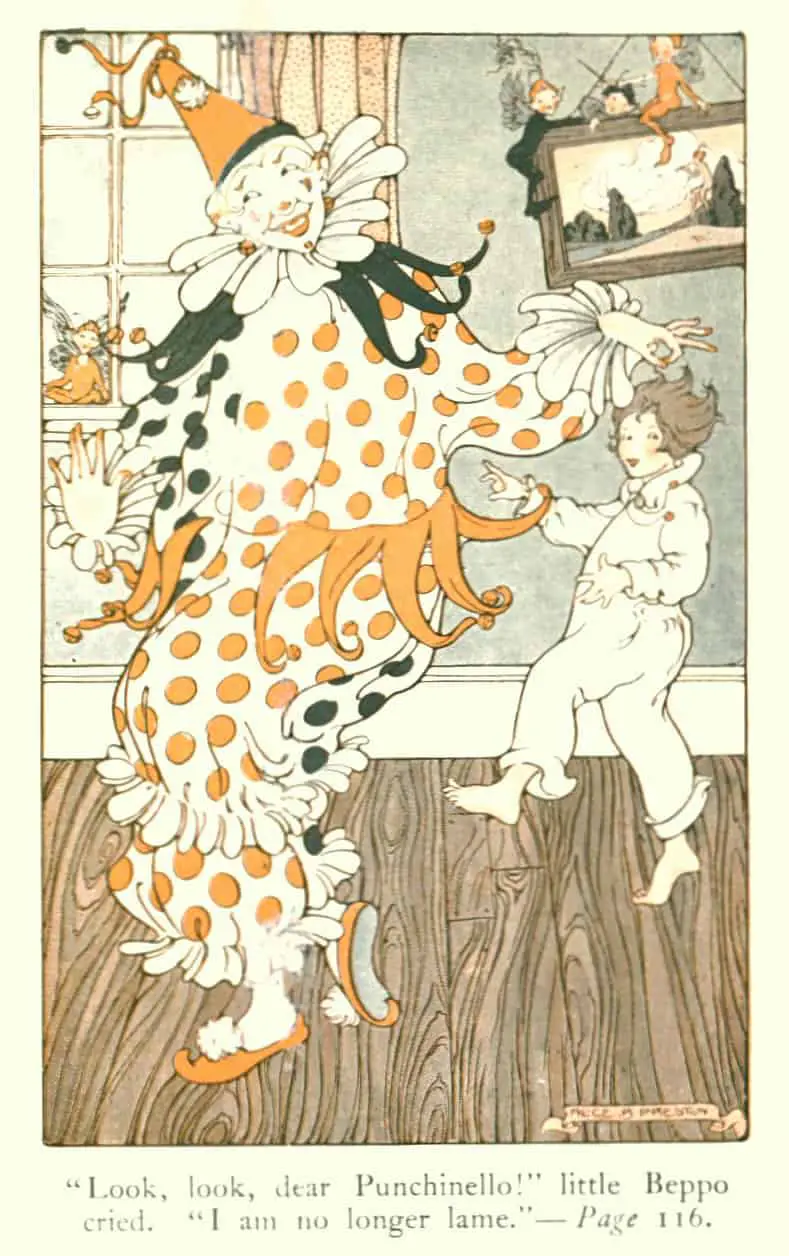

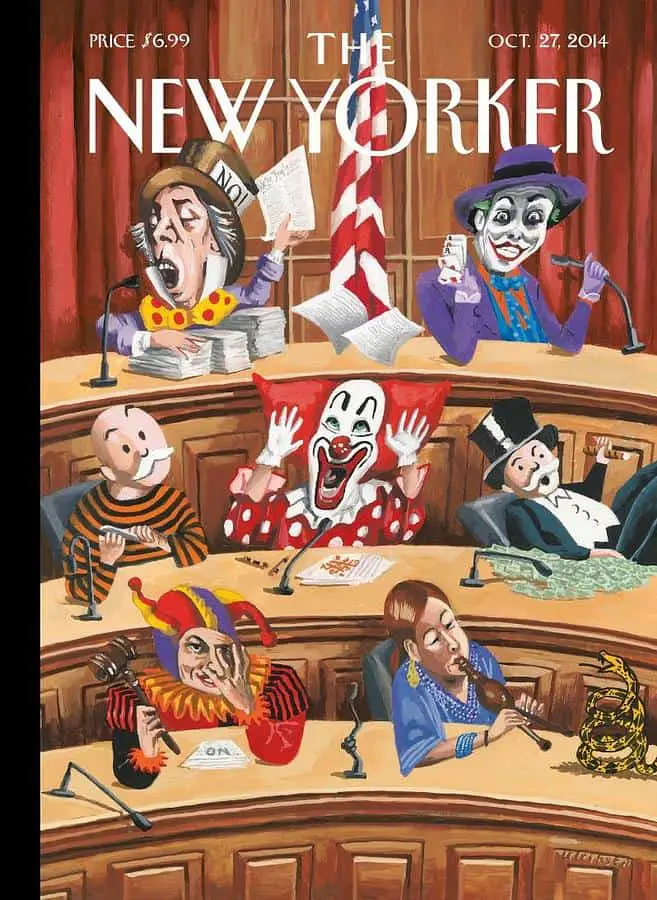

THE TRICKSTER CLOWN

The clown in a story is often a trickster. The lucky thing about villain tricksters: they can be outwitted. They are frequently single-mindedly focused on wreaking havoc and can be therefore be taken by surprise.

THE SCARY CLOWN

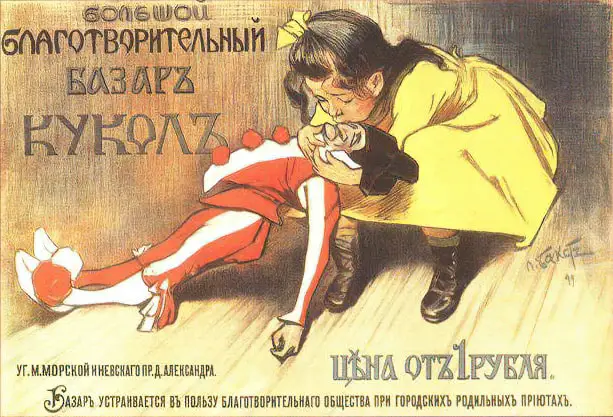

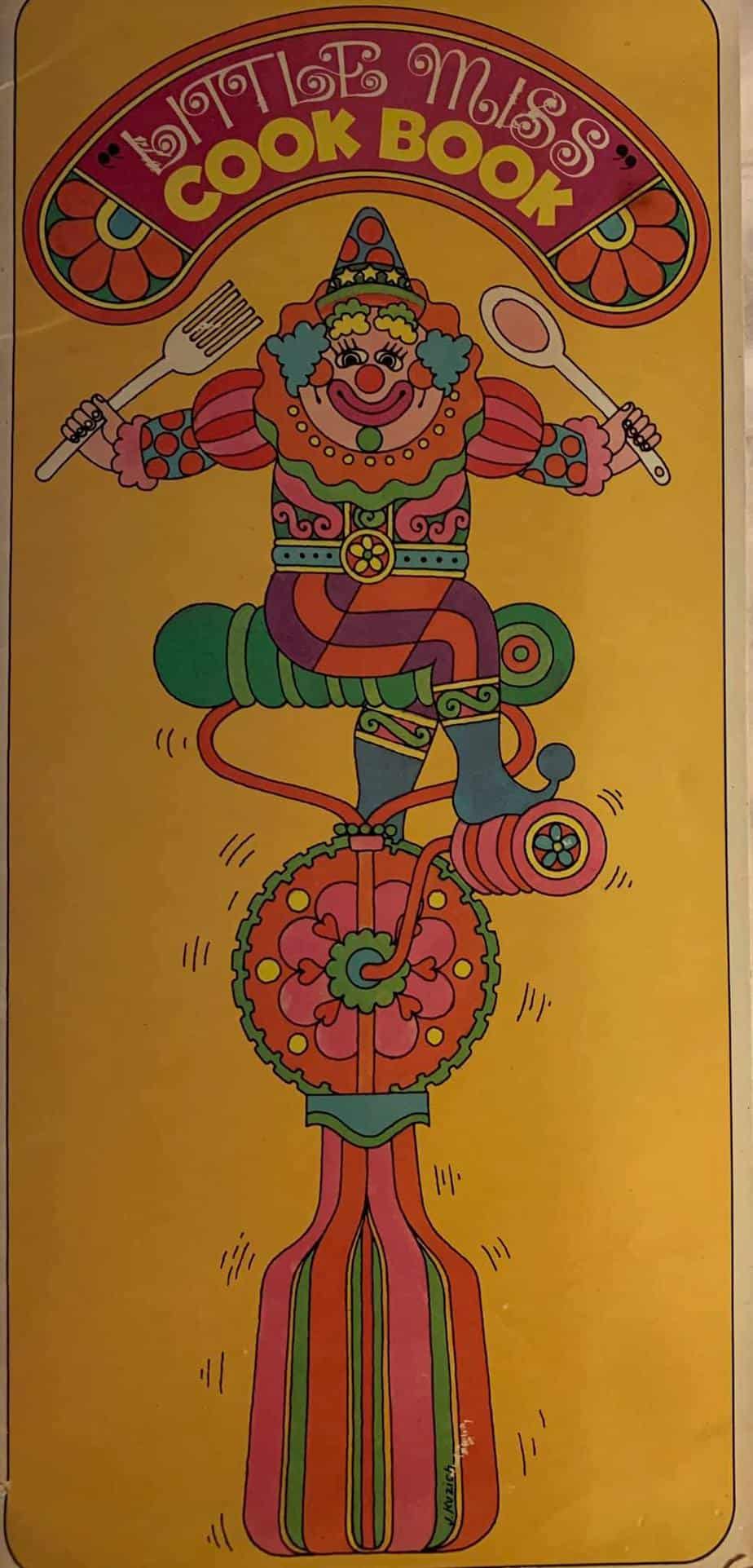

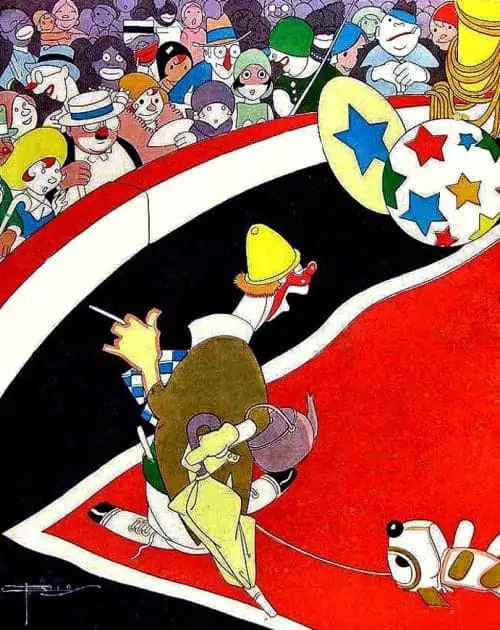

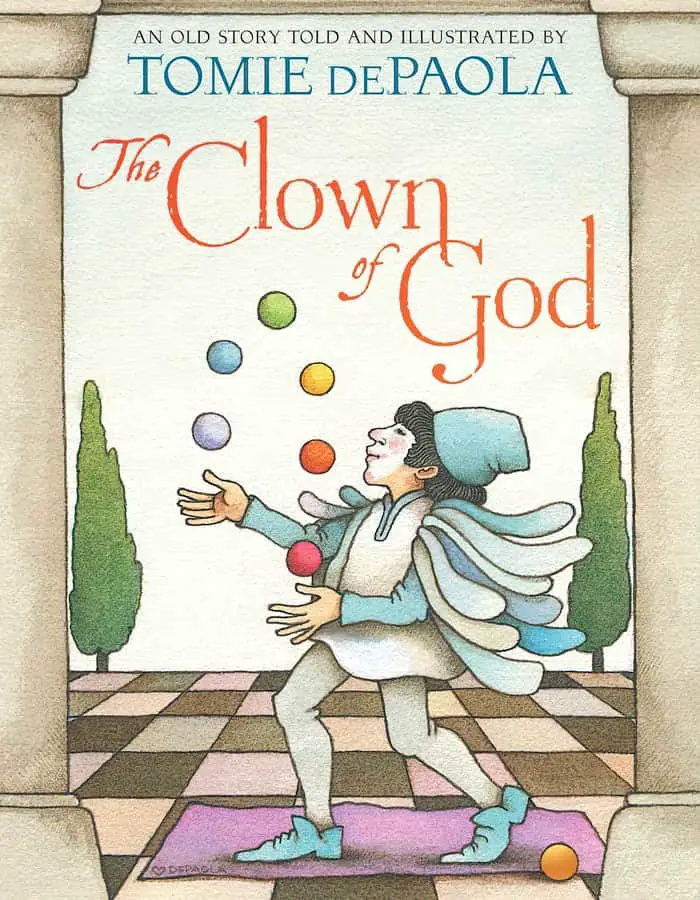

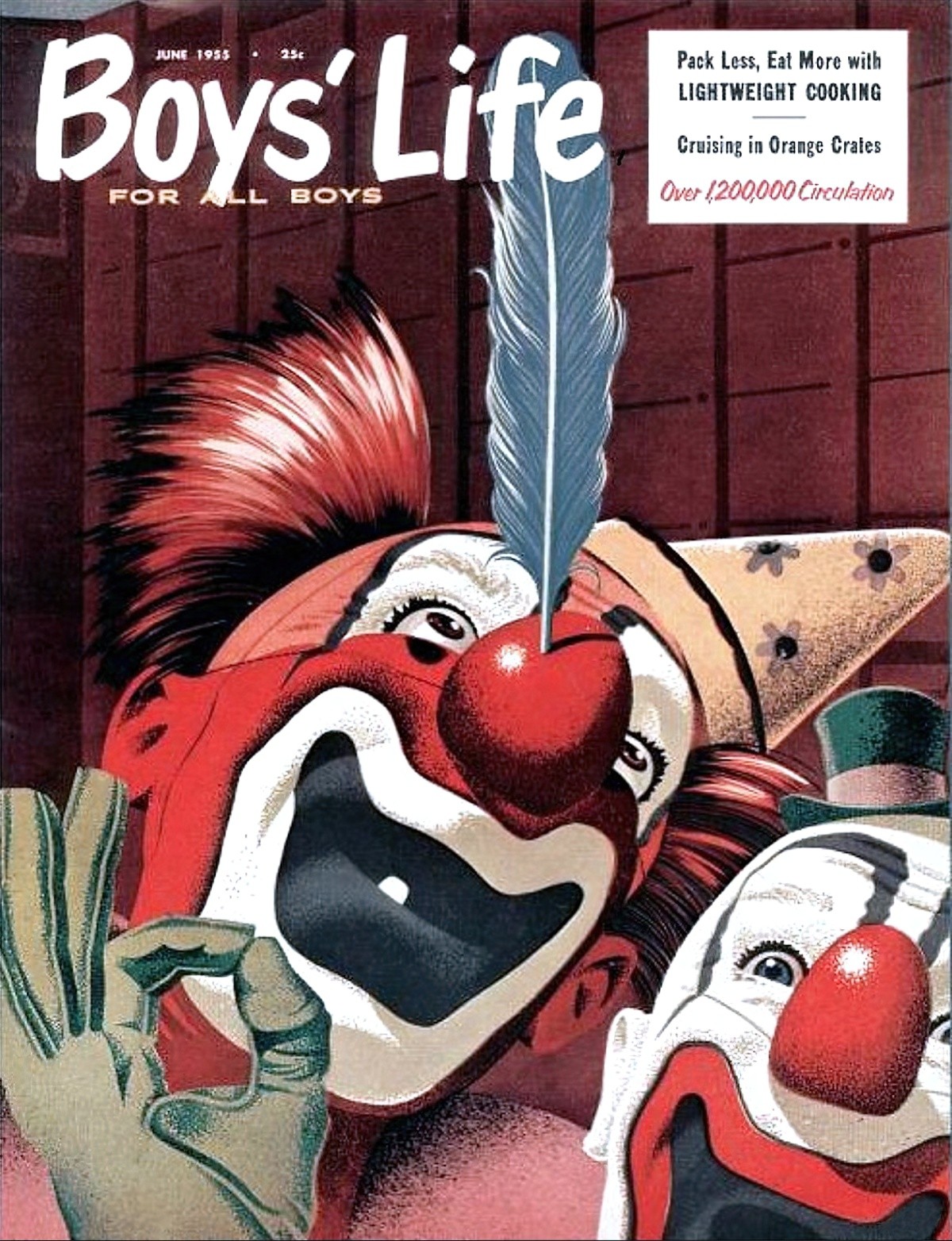

Take a look at children’s stories, toys and merchandise from the 20th century and clown archetypes are everywhere. The Jack-in-the-box below wears a jester’s hat, but also wears the red nose of a clown.

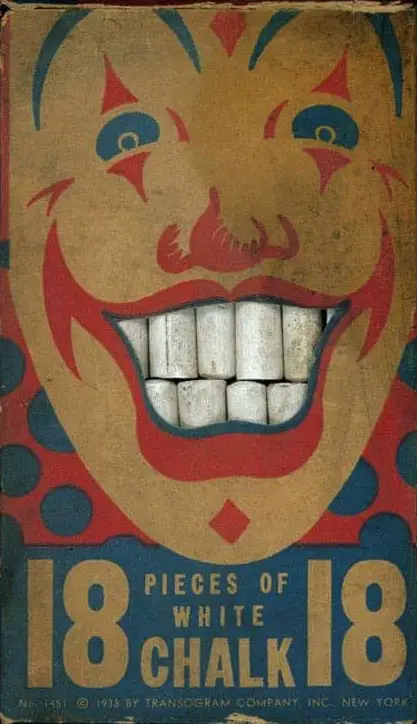

Perhaps children of the first and second Golden Ages didn’t find clowns so scary. Would this chalk packaging fly today? The concept is funny, end result terrifying.

Were clowns always a bit terrifying, though? I don’t think we can blame Stephen King for ruining clowns. An alternative theory: Early children’s stories expected to both scare AND entertain (as well as teach). There was perhaps less expectation that books would be soothing.

Remember, your skeleton is always smiling

Holly Brockwell

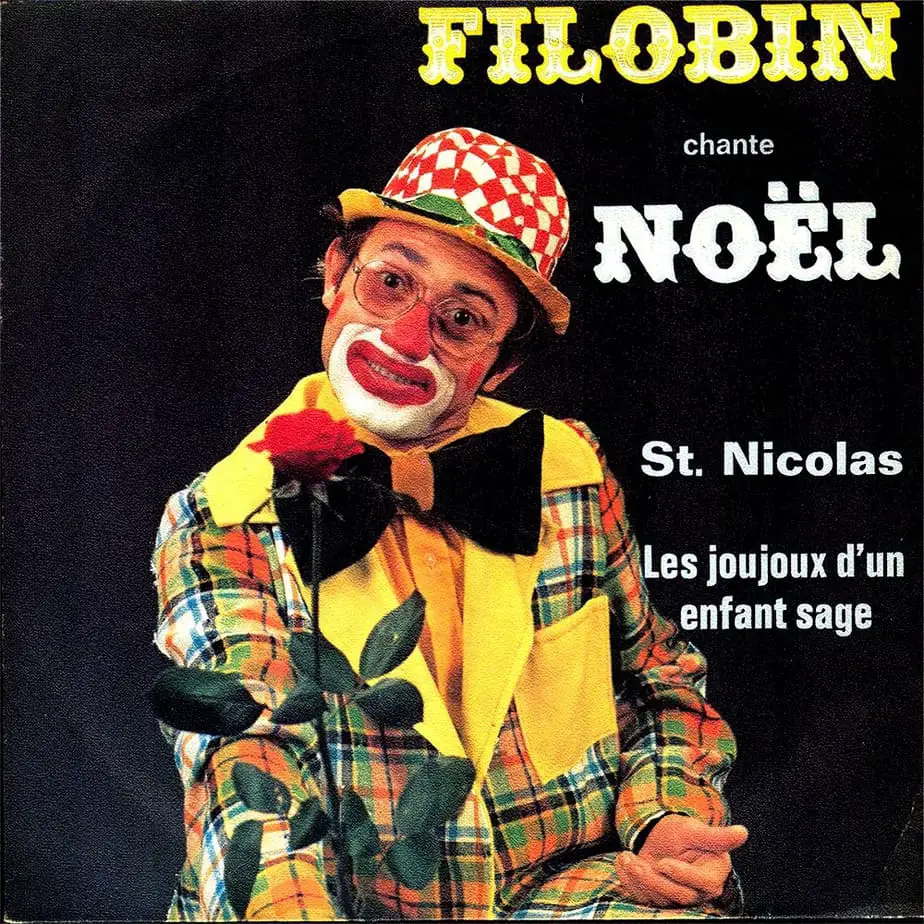

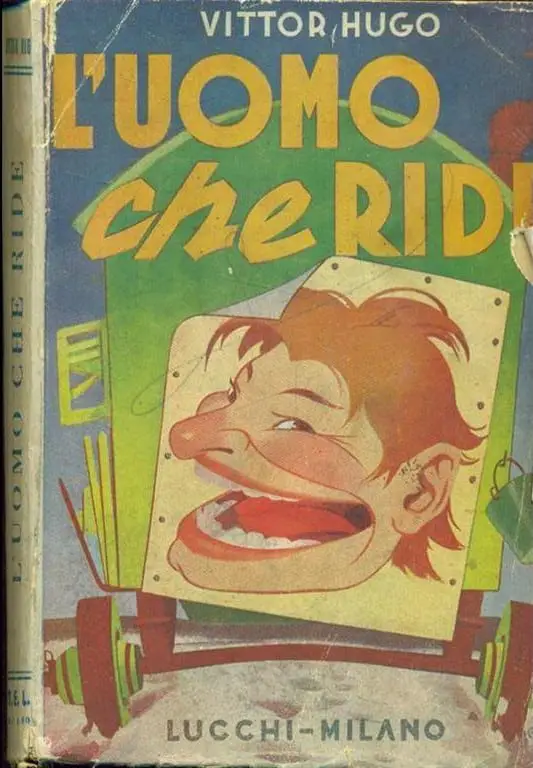

Part of their scariness, I believe, comes from their maquillage — make up so thick and exaggerated that it functions as a mask. The smile only makes it worse. Why? Why is the smile worse?

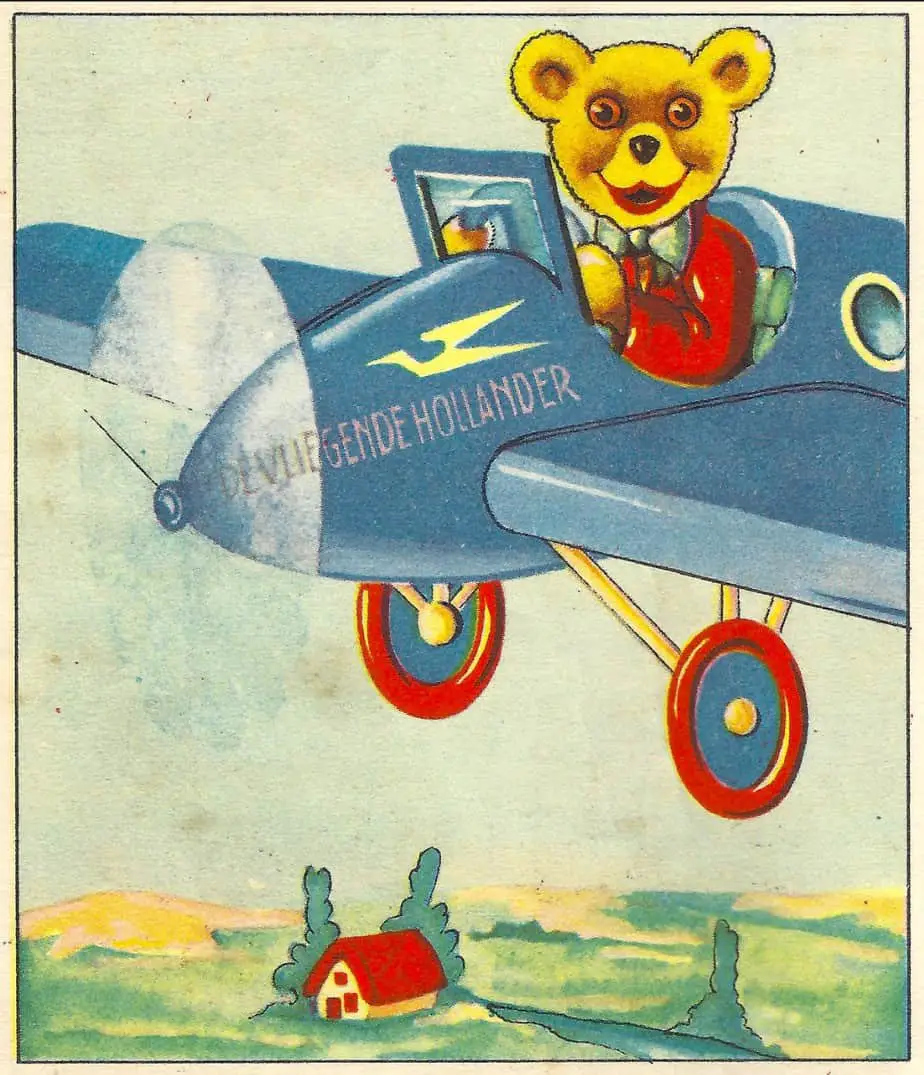

DE BEREN FAMILIE (1950s)

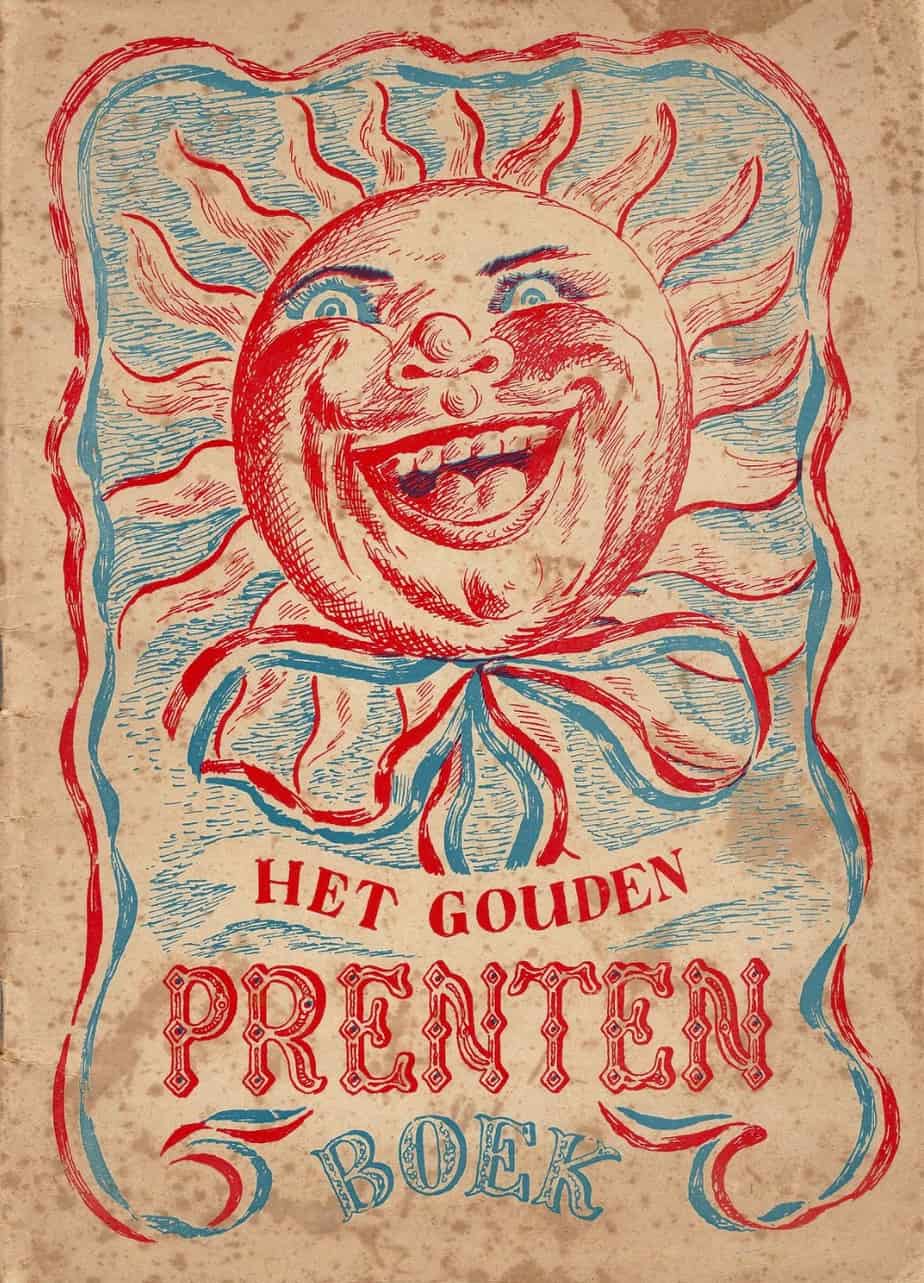

I wondered if those smiles were meant to be creepy until I happened upon this image, and its purpose: The smiling sun below graces the cover of a picture book celebrating the 50th anniversary of Queen Wilhelmina’s reign in Holland (now The Netherlands). I think we can all agree this creepy smile was not meant to be creepy.

Be like Julia Louis-Dreyfus’ glam team and just stay home if you can 💄 pic.twitter.com/QXzb0sgVqW

— NowThis (@nowthisnews) April 11, 2020

When describing the ogre from Greek myth, Baubo, Diane Purkiss has this to say about the associations between terror and smiling:

Fear provokes laughter as easily as screams. Children often laugh when they are frightened. Both fear and laughter depend on surprise, the rupture of expectations. Many demons found their way into the repertoire of comic masks. Aristophanes uses the word for hobgoblin to mean both demon and a comic mask. In an exactly similar way, the Romans hung masks called oscilla (literally, ‘little faces’) in trees to frighten away ghosts, yet the masks could be called by the same naes as the demons they were supposed to frighten. … Play (meaning both theatre and games) is central to demons. Terror, when acted out, is displaced, managed, controlled.

Diane Purkiss, Troublesome Things: A history of fairies and fairy stories

Comedians are supposed to have sad lives, though this isn’t a cliche I entirely endorse, the sad clown not a type I’ve ever come across whereas the mean clown, the selfish clown and the downright unpleasant clown are commonplace.

Alan Bennett, Radio and TV, Untold Stories

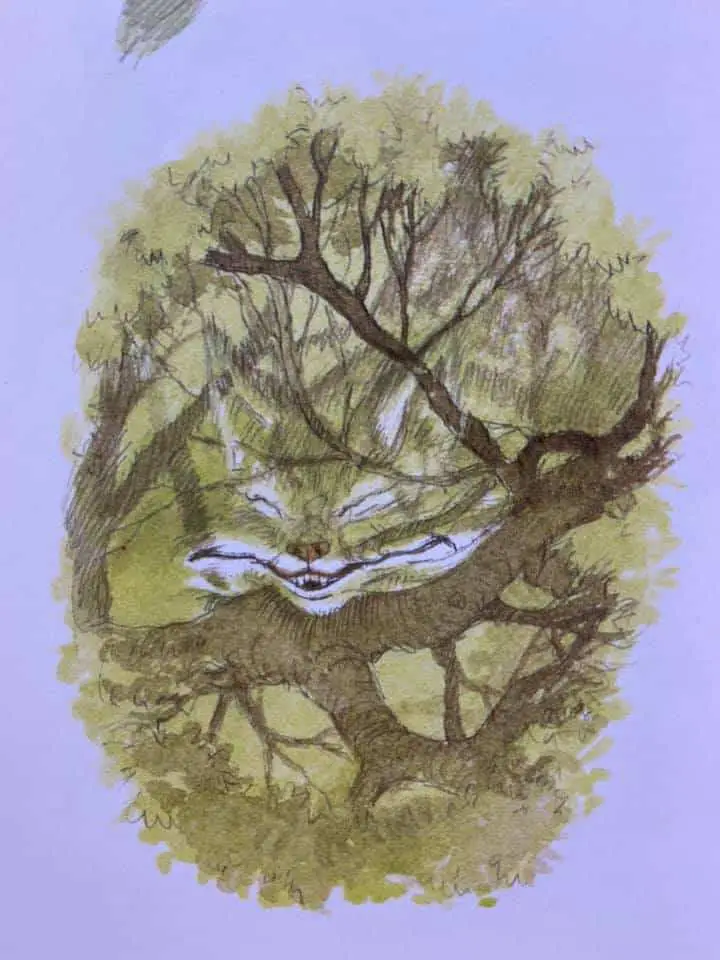

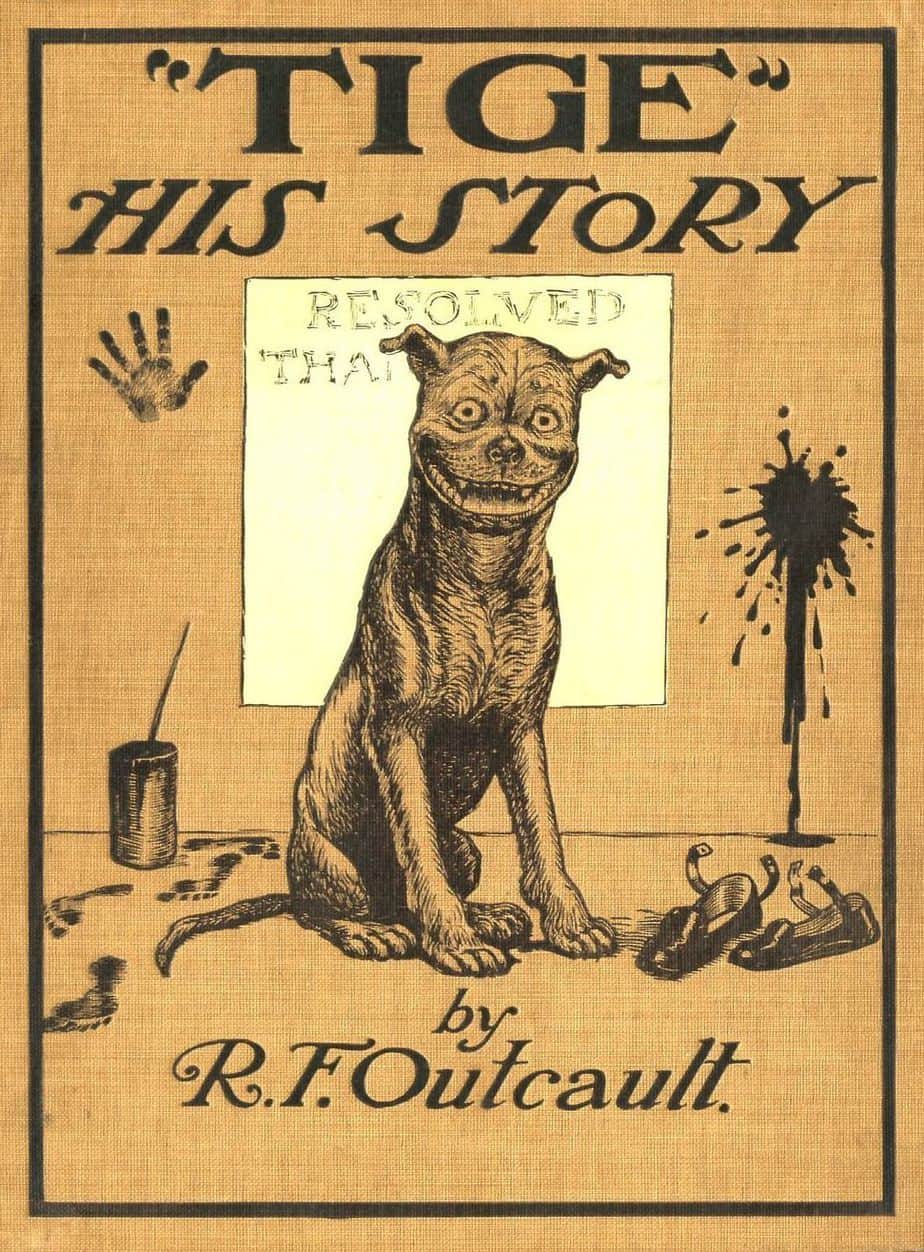

When illustrating a smile, it’s easy to depict a scary grimace. The line is pretty fine. I can’t say what the artist was going for in the dog illustration below, but if they were going for scary, they managed it. I’m reminded of Stephen King’s I.T.

Why can an illustrated smile so easily turn evil? It’s probably an evolutionary thing. When apes and monkeys ‘grin’ at each other they are showing their teeth to convey how they could rip you to pieces if they sunk their incisors into you. Our pet dogs still use their teeth in that way despite thousands of years of domestication. So do people. We are highly attuned to the fake smile. There’s nothing more fake than a painted on smile. This fakeness explains the scariness of the clown’s smile.

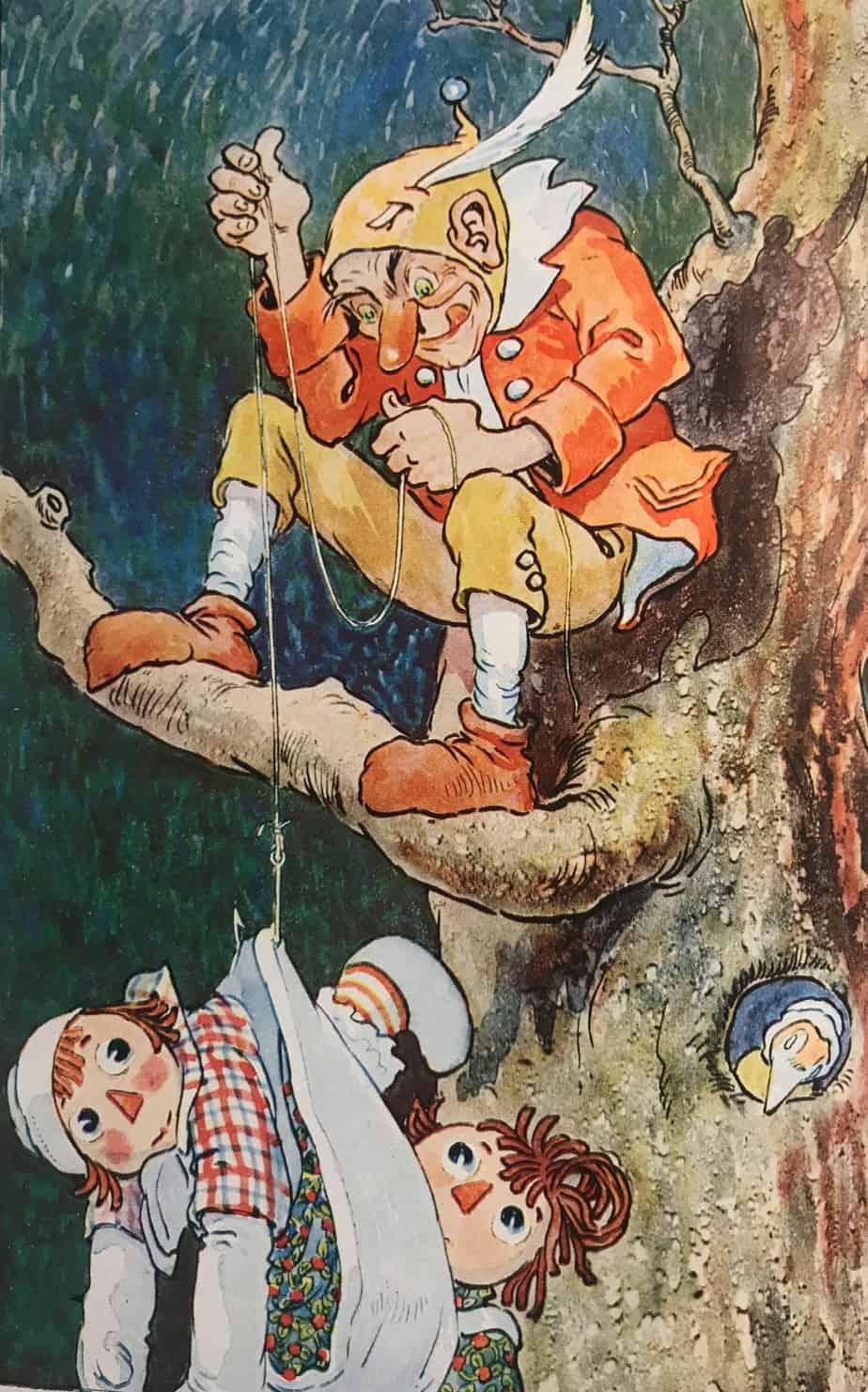

Many children’s book villains have clownish features without conforming fully to the clown archetype. Mean Old Mister Minky of the Raggedy Ann and Andy stories shares in common with clowns those big, wide eyes and the face in rictus, rendered only slightly comical by the concentrating tongue. Mister Minky is a clown-goblin-jester mixture of dastardness.

Gargamel of the Smurfs came later but is a similar archetype to Mister Minky, with his big wide eyes and long nose. The long nose denotes old age but the tufts of hair around the ears with nothing on top now look clownish… We might expect this hair to denote unmarked old age. The receding hairline presents in many men, but this hairstyle (non style?) has been used so frequently in recent clown archetypes one simply cannot get away with it in real life.

Noteworthy is what the Japanese call ‘wakahage‘ (youth balding), which is a less judgemental word than ‘premature balding’ (who’s to say what’s ‘premature’?). All actors who play both Pennywise and Gargamel in the ‘live action’ film adaptations are young men with full heads of hair who need to have their pate covered. The red hair of Pennywise suggests youth, though the balding does not. Again, the juxtaposition is important when it comes to clowns. Juxtaposition creates unease.

THE LONELY CLOWN

Loneliness takes many forms. If clowns are surrounded by people and they take it upon themselves to cheer everybody else up, they fall into the category of the Appreciated Outsider. The lonely person who does not appear to be lonely is wearing a metaphorical mask, which turns into a literal mask in the case of a clown, whose face is so altered by make-up that the real person is no longer visible underneath. There’s nothing more lonely than being ignored when surrounded by people. A rule of the narrative mask: The character who wears a mask will never find happiness until the mask comes off. Clowns must become known before they find friends.

The Lonely Clown archetype doesn’t always look like a clown, and the clownishness of a character doesn’t always endure throughout a story. An example of a temporary Lonely Clown can be seen in American Beauty (1999), in which Lester’s wife Carolyn sings “Don’t Rain On My Parade” in the car. The story is not about Carolyn, and she is not a sympathetic character, but we can deduce that if Lester is isolated within their marriage then Carolyn is suffering equally. We get a few brief glimpses.

In the scene below, the juxtaposition between Carolyn’s inner loneliness contrasts with the upbeat, carnivalesque nature of the song and her rendition of it, which together evoke the classic Lonely Clown idea. Carolyn’s loneliness is only magnified by the happy song, because the audience can see she is wearing a mask.

(Also relevant, we associated clowns with parades.)

An outstanding picture book example of a lonely clown is The Farmer And The Clown by Marla Frazee. In line with picture book ‘rules’, the story ends with a clown character who is no longer lonely, reunited with family in this case. But the Lonely Clown archetype is at play. For a depiction of a lonely landscape conveyed entirely via art work, check out this book as a mentor text.

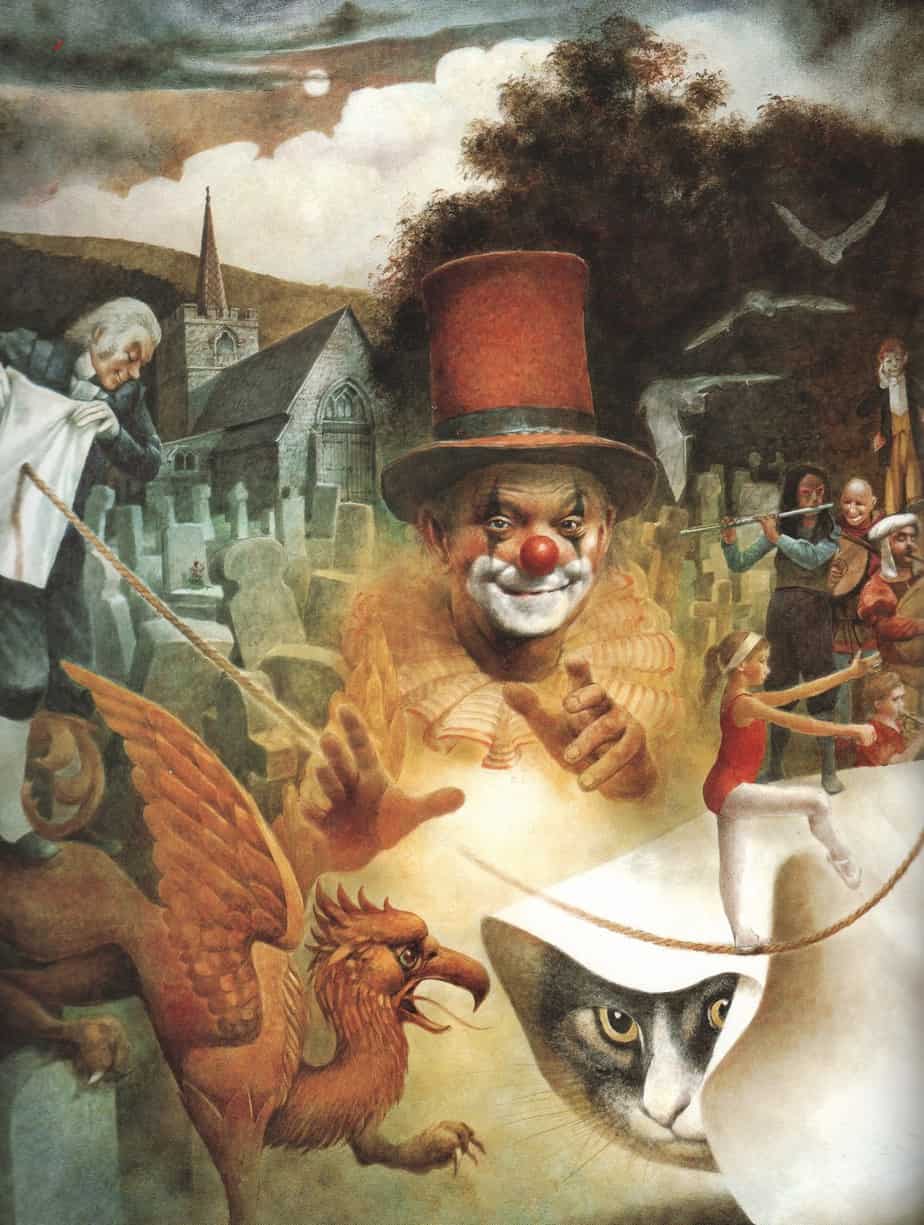

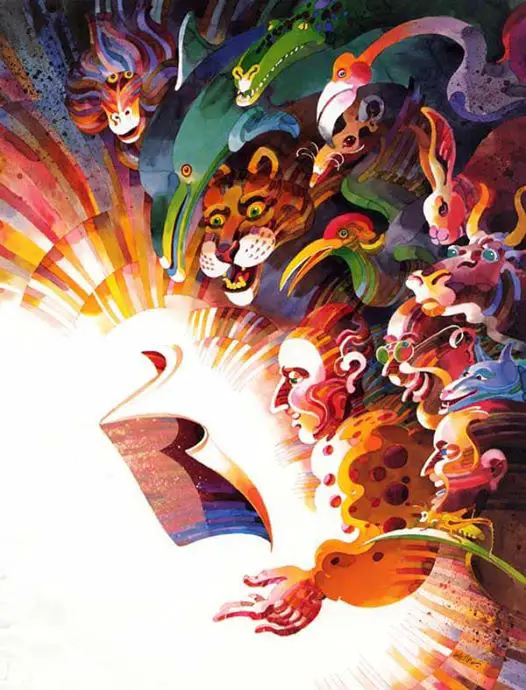

CLOWN AS LIMINAL CREATURE

The clown is an outsider, lonely because he is alone on his stage, never truly known. He exists on the fringe of our culture, and therefore makes the perfect liminal creature. In Ingpen’s illustration above the clown exists in a graveyard, another liminal space, where the living go to greet the dead, forced to contemplate their own mortality.

Header illustration: ‘Hippodrome’ (4 Clowns) – Poster by Jules Chèret, 1882