We like to be scared. Rather, fear sends a rush of adrenaline, and we like that. Scratch that. Maybe it’s the relief we feel once the rush of adrenaline is over.

For the same reason, social media can be addictive. That rush when we hear a reply coming back from a tweet? That rush is partly borne of fear.

Some people have wondered if horror stories are addictive.

Marina Warner argues that the extremes of participatory performances such as rock concerts, orgiastic jubilation such as experienced at raves, and spectator entertainments such as horror films can be viewed as rites of passage, testing endurance. They “define…the living, impervious, sovereign self” as well as providing the ecstatic “high” of surviving. The adrenalin high Warner refers to may account for the addictive quality of these activities and narratives.

Daniel, Voracious Children: Who eats whom in children’s literature

Howard Suber also writes about horror and its special appeal with young adults:

The horror film is a genre aimed largely at pubescent and adolescent youth — the same people who love to scream on roller coasters and look for out-of-control sensations elsewhere in their lives.

Howard Suber

Is ‘fear’ the best word for the emotion horror evokes in its audience? An alternative is ‘horripilation‘, which describes the feeling of hair rising on the back of your neck.

Disgust may also be necessary for the fun horror recipe. In children’s literature (designed for an audience too young for horror) there is a vast selection of ‘gross out’ stories, which are basically proto-horror stories.

What is horror?

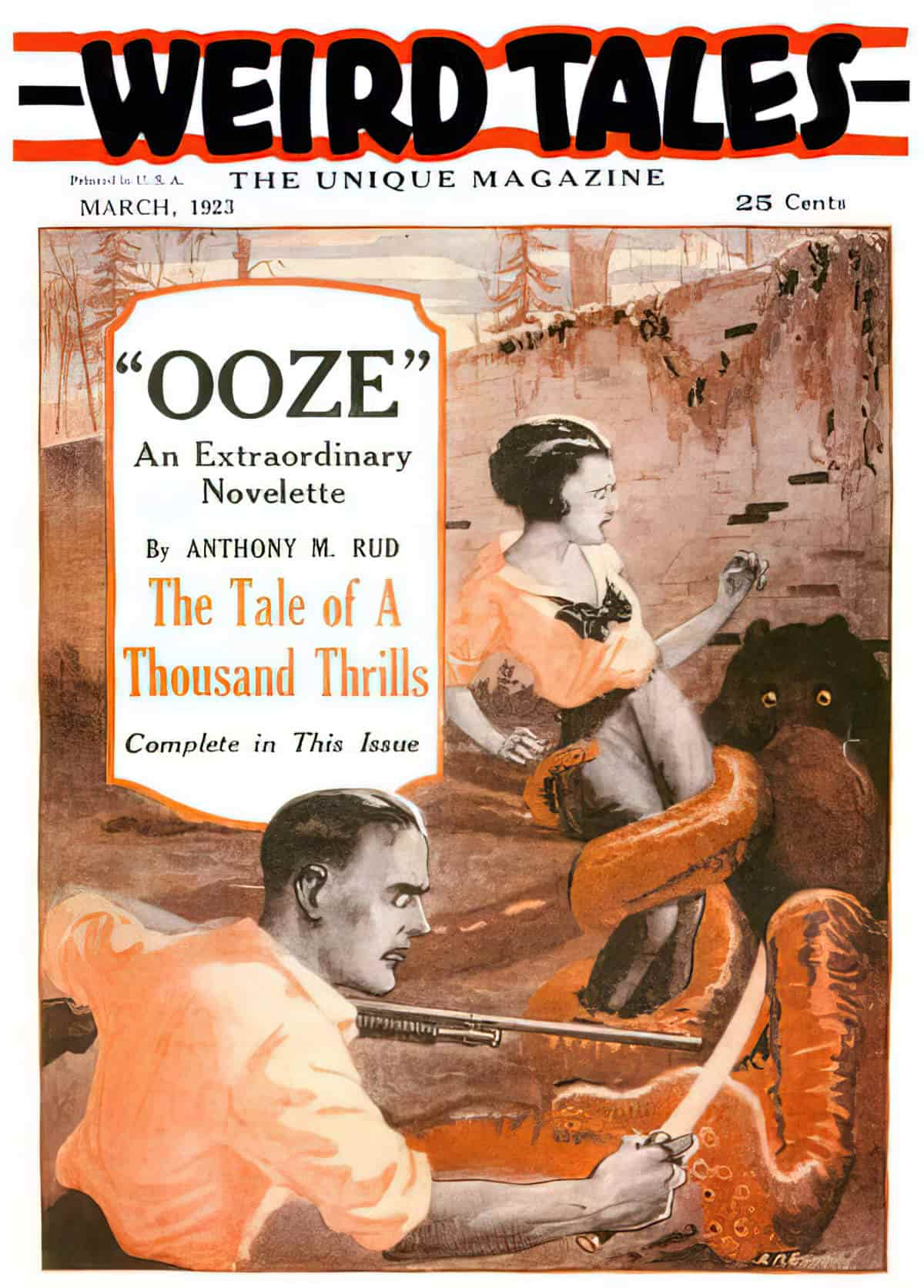

Horror doesn’t have a great reputation. It has a past, and the past isn’t pleasant. There’s a lot of poorly written horror around. Stephen King fans wanted to emulate King’s success, giving rise to profligate, bad horror in the 1980s. Sometimes the term ‘dark speculative fiction’ is used to describe horror, avoiding the negative associations. Many people think of gore and slasher fic when they hear horror.

I really hate the word [horror] because it doesn’t describe to the average reader what my books are about. They think it’s blood and guts and skeletons with eyeballs and so on. I call my books “supernatural thrillers” most often, but terms I also use include “gothic fantasy,” “dark fantasy,” and (my favourite) “gothic bodicerippers.” I’m still waiting for someone to describe my work as Stephen King collaborating with the Brontл sisters. There’s such a strong feminine element, and often a strong historical element, and horror as a term isn’t elastic enough to cope with those extra elements.

Horror author Kim Williams in interview with Tabula Rasa

Splatterpunk sits in the most extreme, violent part of the spectrum.

However, dark speculative fiction describes horror.

The word horror (in a literary sense) has had so many meanings and connotations over the years it’s easy to get confused. Recently, the ‘H’ word has been downright abused, twisted into a salable product, then abandoned as not commercial. It’s become as much an epitaph as a description.

“The Meaning of the ‘H’ Word by editor Paula Guran, OMNI Online, 1997

- horror is an emotion (a strong feeling caused by something frightening or shocking)

- horror is also a brand

- and a stigma

Horror is like mystery; a genre in its own right, but also an element found in many (if not most) kinds of story.

The reason for horror

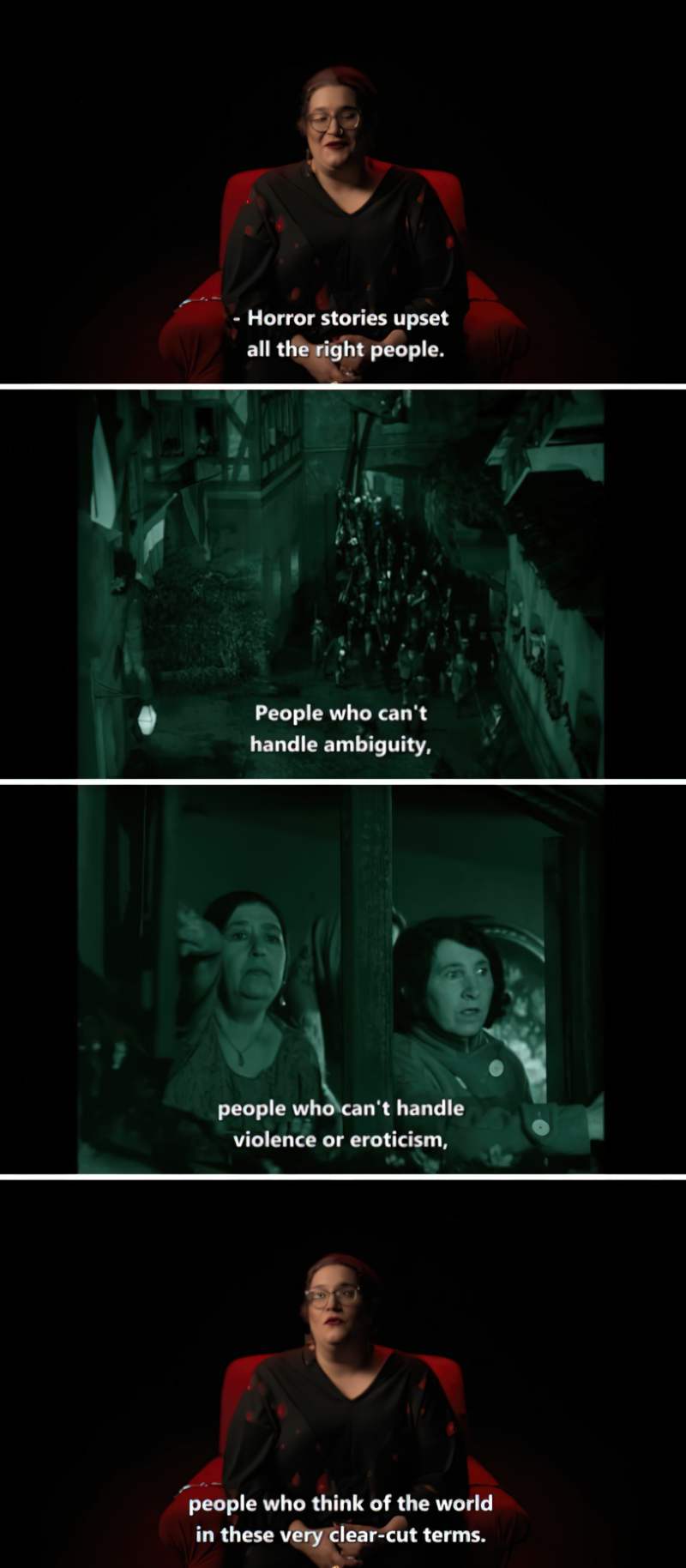

Can horror films add value to our ways of thinking? Can they challenge us to see the world in a slightly different way? Horror, along with Westerns and the entire speculative fiction category is highly metaphorical. Metaphor can be utilised to excellent effect. The best horror adds value.

Starting with Aristotle, the Greek philosopher introduced the concept of ‘catharsis’. The idea is that a scary story can release repressed scary feelings in its audience. (Debatable as to whether that actually works. It may not be the fear itself which is cathartic, but the increaseds sense of in-group intimacy which comes from watching a scary movie with other people.)

this has been said but one big reason some marginalized folks turn to horror is bc it feels honest. it literalizes the experience of “finally, someone is telling the truth.” this is what it feels like to be seen as a monster. to be forced to fight to survive. to be haunted.

growing up with my identities meant that that was one of the only genres that felt, for me & like me, at odds with the “normative” narrative.

off the top of my head some of the storytellers who make me think about this a lot include tiffany d. jackson, carmen maria machado, and jordan peele. her body & other parties rearranged me.

the flip side/origin of this is ofc rooted in the deeply racist, ableist, bigoted history of horror as a genre & who and what characteristics have been designated monstrous. it’s a complicated relationship & some of the most powerful stories are so intentional about it

@mayagittelman (they/she) Night of the Living Queers anthology

I started watching horror films in 2020, mostly because I was drawn to darker material that related to the emotional side of experiencing chronic pain.

Before my chronic pain there’s no way these films would appeal to me. I was a massive scaredy-cat. But it became pretty obvious to me that there was something about being scared that helped ease my symptoms. … In slasher films there’s the constant feeling of trying to escape something.

‘Fear trumps pain’: The unlikely relationship between horror films and chronic pain by Maddy Ruskin

Horror and Freud

Let’s go next to Freud, who believed that horror taps into our collective subconscious. Horror stories can tell us what we’re afraid of. There are commonalities to what we all find reprehensible. Hansel and Gretel taps into the collective fear of an un-nurturing mother. Almost all of us have a mother figure in our lives, making this a universally shared experience. We all fear food insecurity; we all fear getting lost. Freud used the word ‘uncanny’, and published a famous paper about that in 1919.

More recently, Noel Carroll (film scholar) has talked about the negative emotions of distress, displeasure and disquiet manipulated by horror films into something that feels like pleasure.

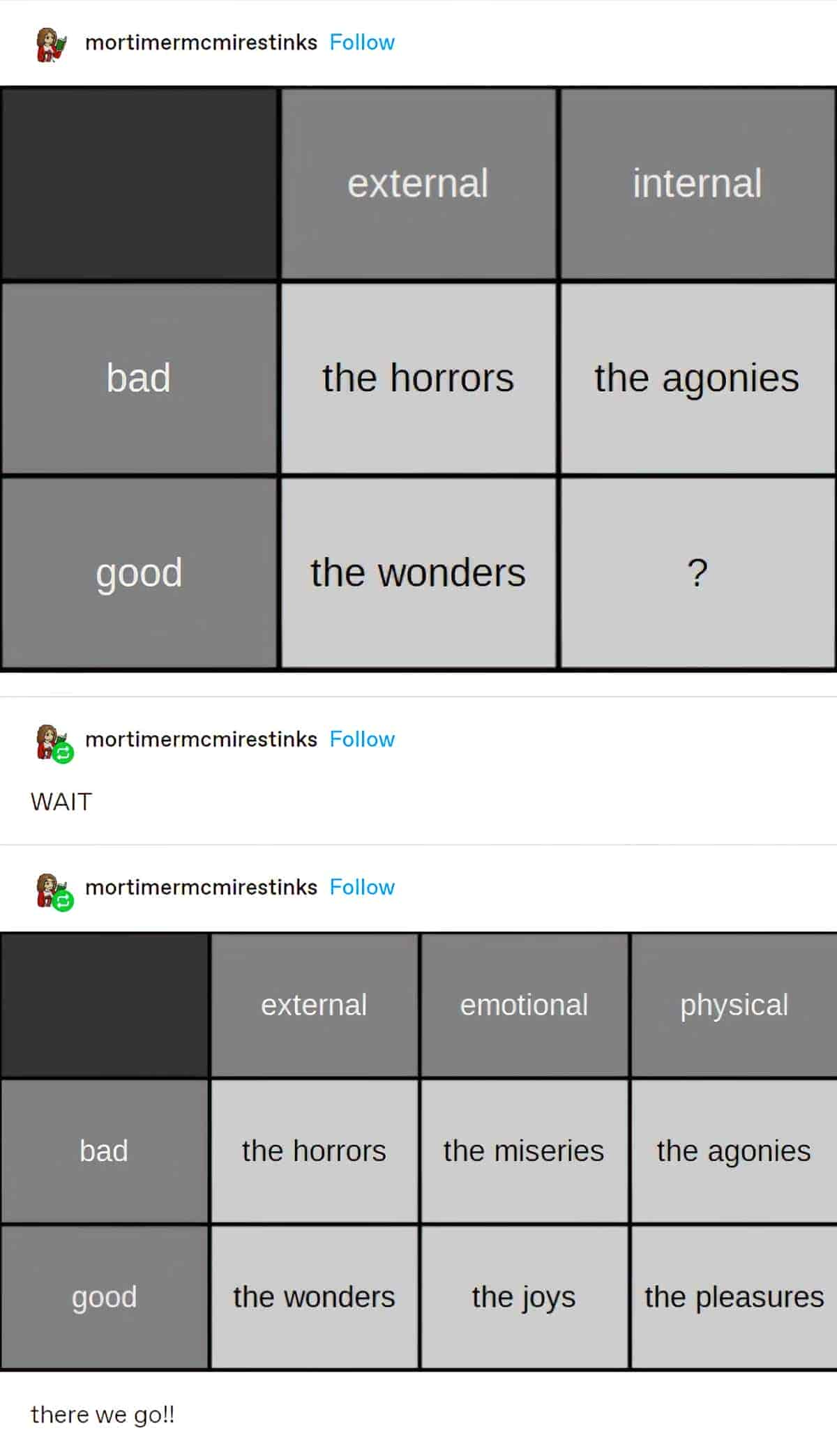

What are the big questions horror tends to deal with? All narratives are about our desire to know something we didn’t know before, but what is the knowledge that horror adds?

Why do monsters exist? What is a monster?

Horror is different from other types of story because horror monsters, by their supernatural, unassailable natures, are inherently unknowable to us.

- In the horror stories of H.P. Lovecraft, the world was once inhabited and ruled by monsters. But now they live in another dimension, eager to return and take over again.

- In splatterpunk, shock is prioritised over scare. (See Edward Lee, Clive Barker)

- Ghost stories are a quieter form of horror because characters know ghosts inhabit their world but the ghosts are seldom seen. M.R. James was one of the first writers of ghost stories who avoided using shock to scare readers. He wrote middle-ground horror: Weird things happen; the character comes face to face with it; must deal with the consequences.

- Stephen King writes contemporary horror and is familiar to most of us here.

- Er*tic horror combines horror and sex.

[Sex in fiction is] always an opportunity to reflect on power, or on the problems of desire, or on the limits of fantasy. I think because er*tica and horror are both designed to produce a physical response they go very well together. And always have. Mrs Radcliffe knew that back in the 18th century when she sent Schedoni in to finish off Ellena with a dagger, and he had to part her nightgown over her sleeping bosom to press the point in.

Horror author Kim Williams in interview with Tabula Rasa

- Dark fantasy combines horror and fantasy. (The ‘dark’ is euphemistic for ‘horror’ and refers to dark emotions.)

- In psychological horror, strange things are messing with people’s minds.

- Weird horror is difficult to separate from general horror, but perhaps refers to the author/publisher’s intention to write plots and elements which haven’t become super familiar to readers yet.

Horror is about humans in decline, reduced to animals or machines by an attack of the inhuman.

Carolyn Daniel

The horror genre is about the fear of the inhuman entering the human community. It is about crossing the boundaries of a civilized life—between living and dead, rational and irrational, moral and immoral—with destruction the inevitable result. Because horror asks the most fundamental question—what is human and what is inhuman?—the form has taken on a religious mind-set. In American and European horror stories, that religious mind-set is Christian. As a result, the character web and symbol web in these stories are almost completely determined by Christian cosmology.

See also: Why is the Bible so much like a horror movie? from OUP Blog

In all horror stories, the opponent wants to belong. They want to enter the human community but we won’t let them.

Differences Between Western Horror and J-Horror

Not all horror is from the West, of course. If you’ve ever watched Japanese horror, for example, you’ve probably noticed a distinct difference. Japanese horror does not make use of Christian symbolism because Japan has its own super creepy folklore from which to draw. Naturally, Japanese horror draws from Western traditions and, increasingly, vice versa.

Japanese horror is Japanese horror fiction in popular culture, noted for its unique thematic and conventional treatment of the horror genre in light of western treatments. Japanese horror tends to focus on psychological horror and tension building (suspense), particularly involving ghosts and poltergeists, while many contain themes of folk religion such as: possession, exorcism, shamanism, precognition, and yōkai.

Wikipedia

Chinese horror is similar to Japanese though often includes some comedy elements. Given that certain tricks — such as mechanical behaviour — are used in both horror and in comedy, the link is more natural than at first it seems. A comedic scene can also heighten the terror that follows, and give the audience a break before enduring more.

Bollywood also produces horror films, and they include lots of singing and dancing!

How The Horror Genre Is Evolving

The origin or horror can come from:

- Whatever lies beyond death (Dracula)

- Demonic forces (The Exorcist)

- Fooling around with Mother Nature (Frankenstein)

Or the horror can be supernatural in a different sense, without religious connections at all but still not what we customarily think of as “natural”. It can, for example, be the super science of The Terminator or the biological horror that seems “unnatural” in Alien. Sometimes, what’s unnatural is merely a warped mind, as in Psycho and Friday the 13th.

Howard Suber, The Power of Film

slasher horror: you better not have premarital sex or gerald “the stabber” douglas is gonna getcha

creepypasta: once there was a teen named alex and he was bullied so hard that he and the acid disfigured him so and he started killing everyone so they call him george the attacker

/x/: there was the skinwalker who stole my best friend’s voice and then man door hand hook car door

r/nosleep: my wife was hungry for raw meat and then she gave birth to The Satan. he looked me in the eyes and said “don’t go outside past midnight or else the eyeless ones might notice.” but it turns out i never had a wife or son and the world ended 5 years ago on this very night.

r/twosentencehorror: i ran out of bloodmilk for my cereal. luckily, the creature provides.

mascot horror: this is silly wiggles, the candy giraffe! explore the silly wiggles candy emporium after dark! the secret ingredient is Love™! also the hidden video tapes will reveal that “Love™” is actually the copyright name for the consciousness of tortured children, mixed with the ground organs of factory workers.

indie horror: i can’t describe this, there are only 7 pixels so idk what’s going on

kragehund-est

Why people enjoy horror

Here’s one taxonomy of reasons for watching horror. Marvin Zuckerman was all over this at the end of the 1970s.

Later, in the mid 1990s, Dr Deidre Johnston came up with four reasons adolescents watch graphic horror:

- Gore-watching — low empathy, strong identification with the ‘baddie’

- Thrill-watching — high empathy, high sensation seeking motivated by the suspense

- Independent watching — high empathy for the victim and with positive feelings at the end of the story

- Problem-watching — high empathy for the victim but negative feelings of helplessness at the end of the story.

In the mid 1980s we had Gender Socialization theory by Zillman, Weaver, Mundorf and Aust. They compared a group of 36 men with 36 women (using a now-outdated gender binary, of course) and concluded that the men found the horror films fun while the women were distressed. (Did the young men enjoy the movie more because the women were distressed? Is it possible to tell from someone’s outer reaction how scared they feel on the inside?) There’s a whole lot going on there.

Sensory horror

Sensory horror is horror which emphasises the senses. While all horror does this to some degree, sensory horror will do it more: squishes and squelches and spurts and all of that.

The Target Audience Of Horror

Netflix is well aware of their target audience when it shows us three distinct categories of Horror:

- Gory (Let The Right One In, Teeth, Let Me In, You’re Next) — believe it or not, Ten Little Indians was the play and 1965 film that started the Slasher genre. This film is itself not listed as horror on IMDb — it’s a blend of crime, mystery and thriller.

- Supernatural (Splice, Insidious, End of Days, Mirrors)

- Teen Screams (Troll Hunter, Hansel and Gretel, Playback, Hellraiser)

I haven’t yet come across the category for Middle-aged Woman Screams. However, as Howard Suber notes, some filmmakers have learnt how to harness the allure of horror and modify it for a different audience:

Attracting people who are not part of this constituency is often difficult. The Exorcist and Rosemary’s Baby did so by dealing with families in a serious way — something the mostly young audience for horror films isn’t especially interested in seeing.

Howard Suber

What Most Horror Stories Have In Common

TENSION

Horror requires tension. That’s such a broad spectrum word. How does a storyteller create tension?

- Mystery (the identity/nature of the opponent is often kept from the audience)

- Suspense

- Gore (in some subgenres of horror)

- Shock (e.g. with jump scares)

- Reveals and reversals

- Horror-like mise-en-scène (staging) in film (costume, incongruous SFX, high and low camera angles, tracking shots, variation in closeness of camera to subject).

- Lighting: up-lighting, silhouette, spotlighting, underexposure, chiaroscuro, emphasis of shadows

Common Symbols In The Horror Genre

Light and Dark is important in horror. We all know that light = good, dark = bad. (Compare to the white hat, black hat symbolism of Westerns.)

Since Christian symbols form the basis of horror stories from the West, we often have the cross, which has the power to turn back even Satan himself.

Before Christianity, though, there was horror in myth. In myth, animals were symbolic in a similarly binary way. Good animals:

- horses

- stags

- bulls

- rams

- snakes (believe it or not)

In myth, if you came across these animals, they had the power to lead you to behave properly and become a better person. But this all changed once Christianity came along. The devil kind of ruined any sort of creature with horns.

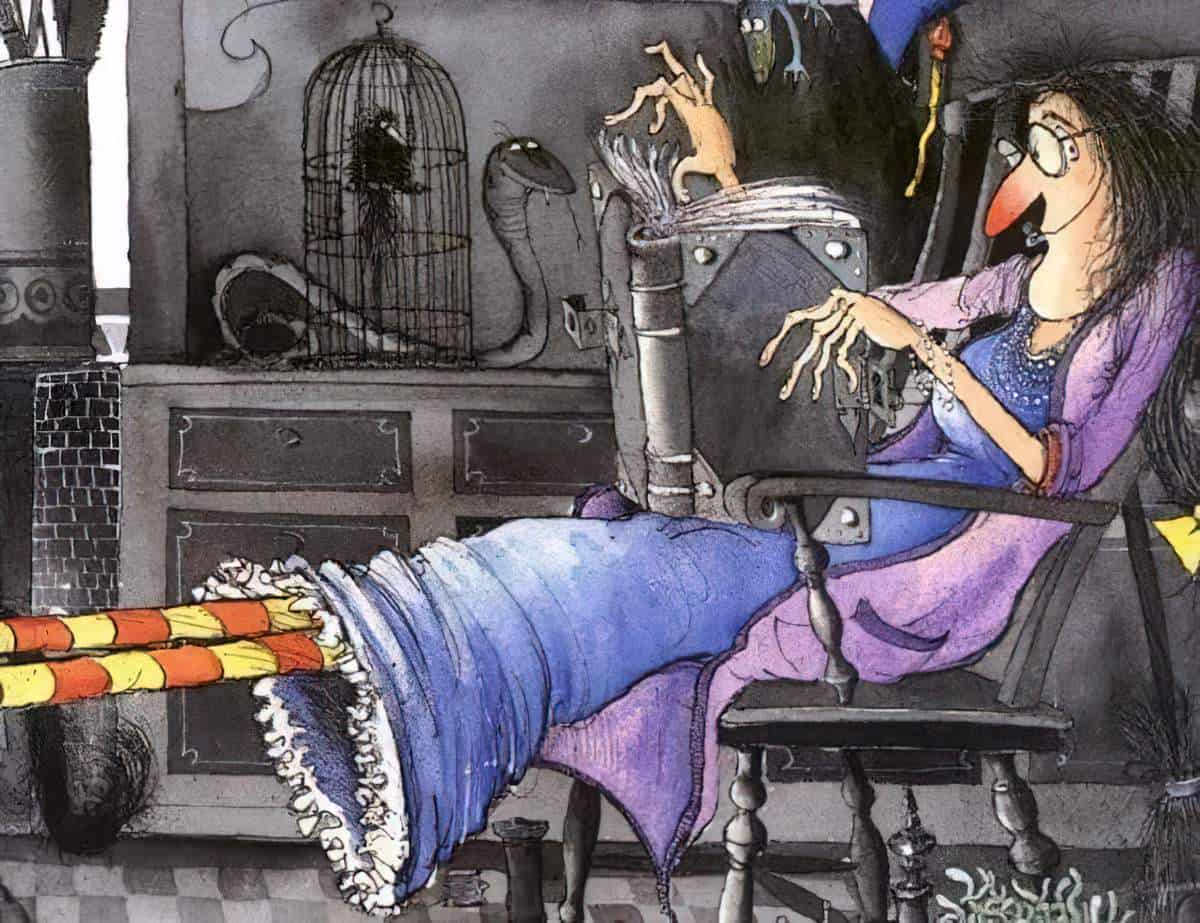

Other picture books make use of horror symbolism but are designed, ultimately, to comfort. The Dark by Daniel Handler and Jon Klassen is one example.

Some picture books are genuinely horrific even though they are picture books. The Wolves In The Walls by Neil Gaiman and Dave McKean is one example.

Mechanical Behaviour

This is commonly used in horror, as it is also used in comedy (refer to The I.T. Crowd: “Have you tried turning it off and on again?” and in Meet The Parents, with the airport woman who won’t let Gaylord Focker board the plane early even though there is no one else waiting).

Examples of horrific mechanical behaviour:

- Whenever the sun sets the Wolf Man/vampire appears

- Bates in Psycho ‘can’t help’ himself, and becomes the cog in a horrible psychic machine

FOR FURTHER INVESTIGATION

Audiences don’t scare as easily as they once did. Not only have they seen just about every conceivable brand of horror movie—from torture p*rn to alt-history vampires—they’ve seen real-life terrors that Alfred Hitchcock never had to compete against. Considering this desensitization through saturation, it’s a marvel that one of the biggest horror phenomena of the last decade comes in the historically tame format of a weekly anthology series.

(About the Saw franchise)

With Hallowe’en just passed, here are some collections of the scariest stuff, curated by others.

- 50 People On ‘The Darkest, Creepiest True Story That Terrifies Me To This Day’

- 10 Novels That Will Scare The Hell Out Of You

- Tony DiTerlizzi’s Top 10 Books For Creeping Out Kids

- Top 10 Horror Stories from Stephen Jones

- The Monster Show, a book by cultural historian D.J. Skal, about how horror relates to the economy and failing social nets

- “Understanding the Popular Appeal of Horror Cinema: An Integrated-Interactive Model” by psychologist Glenn D. Walters

- Thoughts on American Horror at Kinephanos

THEOLOGY AND HORROR: explorations of the dark religious imagination ed. Brandon R. Grafius, John W. Morehead (2021)

Scholars of religion have begun to explore horror and the monstrous, not only within the confines of the biblical text or the traditions of religion, but also as they proliferate into popular culture. This exploration emerges from what has long been present in horror: an engagement with the same questions that animate religious thought – questions about the nature of the divine, humanity’s place in the universe, the distribution of justice, and what it means to live a good life, among many others. Such exploration often involves a theological conversation. Theology and Horror: Explorations of the Dark Religious Imagination pursues questions regarding non-physical realities, spaces where both divinity and horror dwell. Through an exploration of theology and horror, the contributors explore how questions of spirituality, divinity, and religious structures are raised, complicated, and even sometimes answered (at least partially) by works of horror.

Contents of Theology and Horror

- Consider the Yattering: The Infernal Order and the Religious Imagination in Real Time by Douglas E. Cowan

- The Theological Origins of Horror by Steve A. Wiggins

- Mysterium Horrendum: Exploring Otto’s Concept of the Numinous in Stoker, Machen, and Lovecraft by Jack Hunter

- Priests, Secrets, and Holy Water: All I Ever Learned About Catholicism I Learned from Horror Films by Karra Shimabukuro

- We Have to Stop the Apocalypse! : Pre- Millennial (Mis)Representations of Revelation and Eschaton in Horror Cinema by Kevin J. Wetmore, Jr.

- Gnostic Terror: Subverting the Narrative of Horror by Alyssa J. Beall

- A Longing for Reconciliation : The Ghost Story as Demand for Corporeal and Terrestrial Justice by Joshua Wise

- Who’s afraid of the Big Bad Wolf?: Two Models of Christian Theological Engagement with Lycanthropy by Michael A. Hammett

- Endings that Never Happen: Otherness, Indecent Theology, Apocalypse, & Zombies by Jessi Knippel (There’s a word for ‘otherness’. It’s ‘alterity’.)

- Do I Look Like Someone Who Cares What God Thinks? : Narrative Ambiguity, Religion, and the Afterlife in the Hellraiser Franchise by Mark Richard Adams

- Ferocious Marys and Dark Alessas: The Portrayal of Religious Matriarchies in Silent Hill by Amy Beddows

- They Say with Jason Death Comes First/ He´ll Make Hell a Place on Earth: The Functions of Hell in New Line’s Jason Sequels by Wickham Clayton

“HOW TO WRITE A BLACKWOOD ARTICLE” AND “A PREDICAMENT” BY EDGAR ALLAN POE

Edgar Allan Poe is best known for his famous short horror stories; however, horror is not the only genre in which he wrote. How To Write a Blackwood Article and its companion piece A Predicament are satirical works exploring the pieces of the formula generally seen in short horror stories (“articles”) found in the Scottish periodical “Blackwood’s Magazine” and the successful misapplication of said formula by – horrors! – a woman author! – respectively.

A Very Nervous Person’s Guide To Horror Movies

Horror fans are attracted to movies designed to scare us, but others shudder already at the thought of the sweat-drenched nightmares that terrifying movies often trigger. The fear of sleepless nights and the widespread beliefs that horror movies can have negative psychological effects and display immorality make some of us very, very nervous about them. In A Very Nervous Person’s Guide To Horror Movies (Oxford University Press, 2021) horror expert Mathias Clasen examines the psychological science of horror to address myths and correct misunderstandings surrounding the genre. Clasen addresses questions such as What are the effects of horror films on our mental and physical health? Why do they often cause nightmares? Aren’t horror movies immoral and a bad influence on children and adolescents? Shouldn’t we be concerned about what the current popularity of horror movies says about society and its values? While media psychologists have demonstrated that horror films indeed have the potential to harm us, Clasen reveals that the scientific evidence also contains a second story that is often overlooked: horror movies can also help us confront and manage fear and often foster prosocial values.

New Books Network

Reel Terror: The Scary, Bloody, Gory, Hundred-Year History of Classic Horror Films

Filmmakers discovered in the early twentieth century that Americans would gladly pay to be scared to death. As the decades marched on, dismissive critics regularly wrote obituaries for the relentlessly popular horror genre, even as other kinds of films (Blaxploitation, anyone?) disappeared from theaters. David Konow, in Reel Terror: The Scary, Bloody, Gory, Hundred-Year History of Classic Horror Films (St. Martin’s Press, 2012), surveys the history of this much-maligned genre and explains why it refuses to die. As he demonstrates in one eminently readable chapter after another, it’s incredibly “fun” to be afraid. That simple fact helps explain why “the true fans of the genre couldn’t care less what the mainstream or the critics think about horror. It never kept them away from the theaters.” Like all good books, Reel Terror‘s strengths stem from the talents of its author.

New Books Network