“The Yellow Wallpaper” is a famous psychological horror short story written by Charlotte Perkins Gilman.

WHERE TO LISTEN

You may be able to unearth the BBC dramatization of this short story somewhere e.g. on YouTube. “The Yellow Broadcast” was broadcast December 1990.

Charlotte Perkins Gilman; July 3, 1860 – August 17, 1935) was a prominent American feminist, sociologist, novelist, writer of short stories, poetry, and nonfiction, and a lecturer for social reform. She was a utopian feminist during a time when her accomplishments were exceptional for women, and she served as a role model for future generations of feminists because of her unorthodox concepts and lifestyle. Her best remembered work today is her semi-autobiographical short story “The Yellow Wallpaper” which she wrote after a severe bout of postpartum psychosis.

Wikipedia

Many writers summarizing the story as showing how the rest cure resulted in madness for the patient. This is positioned as an extension of the societal oppression of women at the time that Gilman exposes using her passionate narrator. But this is too simple – and disregards the intrigue and complexity of the mind that changes over the course of the story. Pay close attention to the images and patterns of narration: how does Gilman bring the reader into the world of the narrator? How is this world made plausible – up to and through the end? To position this work as a feminist writing can be useful but also runs the risk of reducing the peculiarities of the piece. We may discuss the rubric of feminist writings and how that can be useful to our understanding of the historical context of the story while we attend to the range of questions raised in the piece. What is madness, for example, and can we definitively describe the narrator as mad?

The London Literary Salon

According to Asti Hustvedt in Medical Muses: Hysteria in Nineteenth-Century Paris, “Hysteria was at least partly an illness of being a woman in an era that strictly limited female roles. It must be understood as a response to stifling social demands and expectations aptly expressed in paralysis, deafness, muteness, and a sense of being strangled.” The psychological trauma of being a Victorian woman could well lead to the symptoms described. Contemporary invalidity in many cases was psychosomatic, owing partly to the Victorian aesthetic ideal of the beautiful, thin, pitiable object of affection that is exemplified in figure of the sick, dying or dead woman (see Poe, Tennyson, Dickens, Soker, etc. etc. etc.) and partly to being sick being one of the few ways to evoke sympathy and attention outside of stifling domestic life.

I hardly have to mention that being an invalid was also an escape from the crushing burden of domestic work and the immense pressure of conforming to the expectations placed on a Victorian woman. Victorian texts are full of long convalescences of women complaining of vague paints, as well as the doubts of those around them of how legitimate these complaints may be. This is not to say that these women were “making it up,” but rather that suggestion, stress, and trauma all had a role in the “culture of invalidity.”

I think this excerpt is from Medical Muses

Also important to know: Dr. Silas Weir Mitchell, a pioneer in the study of nervous conditions, urged Charlotte Perkins Gilman to treat her ‘hysteria’ by abstaining from her work as a writer, and to “never touch a pen, brush or pencil,” as long as she lived.

THE YELLOW WALLPAPER AND FRANKENSTEIN

What has Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1888) got to do with “The Yellow Wallpaper”? Both are examples of feminine gothic texts. Mary Shelley ‘s tentpole novel explored themes such as transgression of gender roles and postpartum depression. Written later the same century, “The Yellow Wallpaper” intertextualises Frankenstein in similar ways.

Both stories:

- Are about complete isolation

- Present a typical feminist gothic reversal

- Create a picture of monsterfied male control (rather than an actual madwoman)

In “The Yellow Wallpaper”, the narrator creates another woman in the wallpaper. This woman is both her double and her Other. Gothic texts feature a lot of mirrors and reflections. This wallpaper is basically a gothic mirror. Anyway, this gothic mirror, ahem, wallpaper, reflects the monstrous state of the female main character.

This figure multiplies into the image of the creeping women of the ambiguous ending. Likewise, the narrator herself creeps over her husband’s body.

Frankenstein was the first Gothic text to let the Othered have a voice. Likewise, “The Yellow Wallpaper” is told through the viewpoint of what some commentators have called “the monstrous-feminine”, describing a woman who doesn’t conform to expectations of femininity. (Neo-gothic work explores that a lot more deeply and widely.)

WHAT HAPPENS IN THE YELLOW WALLPAPER?

- Else and John rent a colonial mansion — ‘ancestral halls’ for the summer partly because there are repairs going on at home, partly because John figures it will be a good place for his wife to get better.

- Else can’t fathom how this huge house with its extensive grounds is being let so cheaply — she figures it must be haunted or something. She doesn’t mention this to her logical husband who has no time for such fancies.

- John won’t let them take the room on the ground floor so she is forced to spend her days in the sunlight-filled top floor.

- Else spends her days upstairs in this airy attic, or strolling around the gardens trying to get better.

- All the while, a nanny takes care of her baby and the husband’s sister takes care of the housekeeping.

- She is not allowed to write, even though she wants to, because her husband thinks it will tip her over the edge. So she writes this diary in secret.

- Her own side of the family visits briefly.

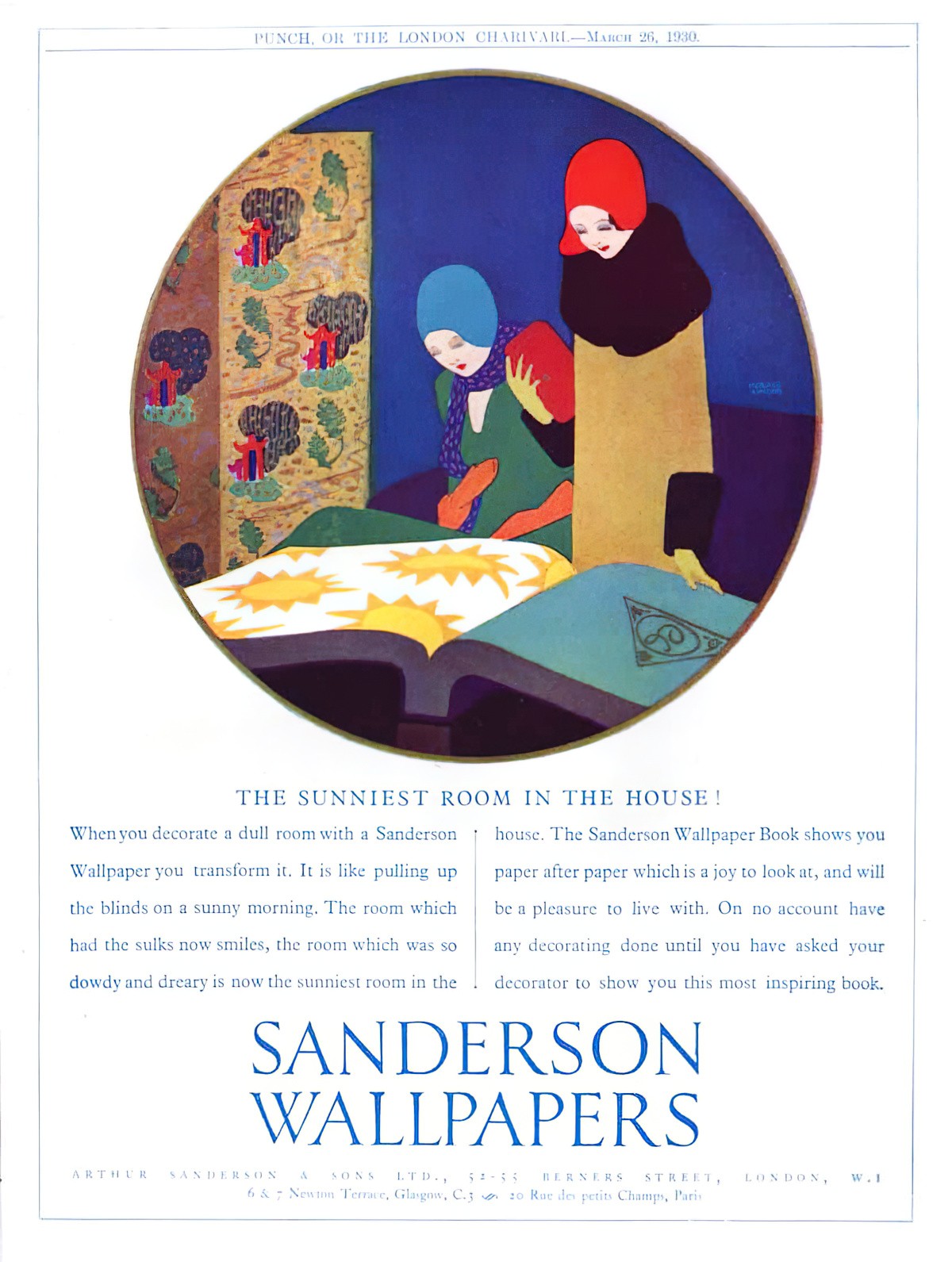

- All this time, the yellow wallpaper is driving her balmy. It seems to be an alive thing, half alive, half dead. The husband considers her issues with it part of her psychosis and refuses to change it.

- After a while she consoles herself by thinking at least the baby doesn’t have this room, with the terrible wallpaper. She wouldn’t inflict this on any child ‘for worlds’.

- She starts to see the shape of an old woman ‘stooping down and creeping about’.

- Then she starts creeping about herself at night, ostensibly creeped out by the moonlight coming in. The moon is just as bright as the sun.

- John makes Else take more and more naps, which she is actually awake during. She doesn’t tell him this.

- Else starts to become scared of John. She puts this down to the creepy wallpaper.

- One night she and this imagined spooky woman pull off lengths and lengths of wallpaper.

- The night-time creepings get worse and worse and she even starts gnawing at the bed. She locks the door so no one can get in.

- But then when he does come in, he faints. We assume he’s lying there for quite a long time, and he may have seen something more than what has been described to us, the readers, but what is it? That is left to us.

- The reader might rread this story as a owman’s escape into madness, or as suicide, suggested by the first encounter with a strangled woman in the wallpaper. However you read it, the author refuses to tidy it up nicely for us, restoring the female main character to the symbolic order.

CHARACTERS

Though Else describes herself as an ordinary person — usually unable to afford to rent such a grand house for three months — this couple are still upper-middle class. The husband is a respected physician who is able to take three months off over summer and with the means to hire a nanny and possibly send his wife to Weir Mitchell, who was a real-life American physician and writer, known for his discovery of causalgia and erythromelalgia

Else and John are presented as opposites: Irrational versus highly rational. It is up to the reader to determine what is truly going on between this couple. I do wonder if a contemporary audience would have necessarily understood the dynamic of control and gaslighting, because in the author’s lifetime, there was a whole lot of sexism concerning mental illness in women.

Else

the first person narrator, suffering from postpartum depression

John

the physician husband who is loved by Else but the reader can see his domination over her.

Mary

the nanny, we assume. We know only her name, but the name Mary gives us the idea of the Virgin Mary. (The same effect is achieved in Downton Abbey.)

Jennie

Jennie’s main loyalties lie with the husband, since she is his sister, not Else’s. Else is on her own in this state. Her family visit briefly, but it is Jennie who takes over control of the housekeeping. ‘Jennie sees to everything now.’ She is also under the dominance of John, which we can see when she confides to Else that she wouldn’t have minded ripping off all of that wallpaper herself.

SETTING OF THE YELLOW WALLPAPER

The Era

I find it interesting to look at food rituals in stories from an earlier time. In 1892 people were eating the diet now recommended we go back to by the Weston A. Price foundation:

John says I mustn’t lose my strength, and has me take cod liver oil and lots of tonics and things, to say nothing of ale and wine and rare meat.

What else was happening in the world at that time? Well, a couple of Australian states were just starting to give women the vote. It wasn’t until 1893 that New Zealand became the first country in which women achieved sufferage. America came a long time after, but Gilman would have been well-aware of these advances, and keenly aware of the fact that she herself had no right to choose who ran her own country and how it was ran. Women were still very much chattels.

Humanity was about to enter into the first real technological phase. Until this point in history you could go to a big mansion in the countryside and live pretty much like a medieval person for a while. The zipper (for clothing) had only just been patented, allowing women (and men) to finally spend less time mucking around with clothing. But they weren’t widespread as of yet. It was all buttons and buckles.

‘Sky-scrapers’ were becoming a thing in America, with buildings as high as ten storeys high in Boston!

Clement Ader’s flying machine had managed to clear four feet and fly for a full 180 feet. Humans were starting to really consider taking to the air.

The first self-service restaurant opened in America in 1892.

The General Electric Company was formed.

And it wasn’t until 1893 that The American Bell Telephone Company made the first long-distance phone call.

Around the Western world, the Industrial era had given rise to huge disparities in incomes. In England and in America there were hundreds of thousands living in slums, sending their children out to work, all of that Dickensian stuff. The reason this narrator doesn’t consider herself wealthy is because she’s obviously been exposed to the super rich, for example the Vanderbilt family of Rhode Island, whose guests are handed silver trowels and told they may dig for rubies and sapphires, and whose dogs wear diamond studded collars.

Out in the Wild West, the buffalo population has been reduced to just 1000 (whereas just 100 years prior it had been 20 million).

In the medical world, it wasn’t until a couple of years after this story was published that the Pasteur and Jenner versions of vaccinations were a thing.

Some people actually thought there would be people living on Mars — an idea made popular by Percival Lowell, a wealthy astronomer.

Other classic works produced around this time: A Picture of Dorian Grey (Oscar Wilde was going through a productive period), The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, Tess of the d’Urbevilles,

Meanwhile, in Japan, it’s hard to believe it was so recent, but after the fairly recent Meiji Restoration, the samurai class were trying to claw back control of the country and there was a massive bloody riot at the 1892 general election, where citizens were tortured by a ruthless home minister. (They didn’t manage to take the country back over, obviously.)

The House

Else describes a snail under the leaf setting, but the broken glasshouses give us the idea that all is not well.

The most beautiful place! It is quite alone standing well back from the road, quite three miles from the village. It makes me think of English places that you read about, for there are hedges and walls and gates that lock, and lots of separate little houses for the gardeners and people.

There is a delicious garden! I never saw such a garden – large and shady, full of box-bordered paths, and lined with long grape-covered arbors with seats under them.

There were greenhouses, too, but they are all broken now.

The husband decides that they will sleep in the nursery at the top of the house. It is an example of a light-filled room, which you don’t often find in straight-written haunted houses — remember this is an apparent idyll. We have an example of dramatic irony when Else naively assumes that the bars on the windows are for safety rather than imprisonment, and that the rings on the walls are some sort of plaything — as readers we’ve seen enough Bluebeard tales to realise these are probably used in scenes of torture or something. She even thinks of innocent hi-jinks when concocting the reason for the state of the wallpaper. We see dramatic irony again later when we know that it is Else gnawing at her bed, not those hypothetical children.

The description of this room almost personifies the room, but not quite. The phrase ‘with windows looking all ways’ makes use of the fact that in English we mostly make no distinction between transitive and intransitive verbs, and we can ‘look’ at something or a window itself can ‘look out’ over something. (Many other languages don’t have this kind of flexibility/ambiguity.) The wallpaper itself is turned into something with its own moral code when Else says it ‘commits every artistic sin’. We’ve got the Christian symbolism creeping in there, too, which pervades the Western horror tradition.

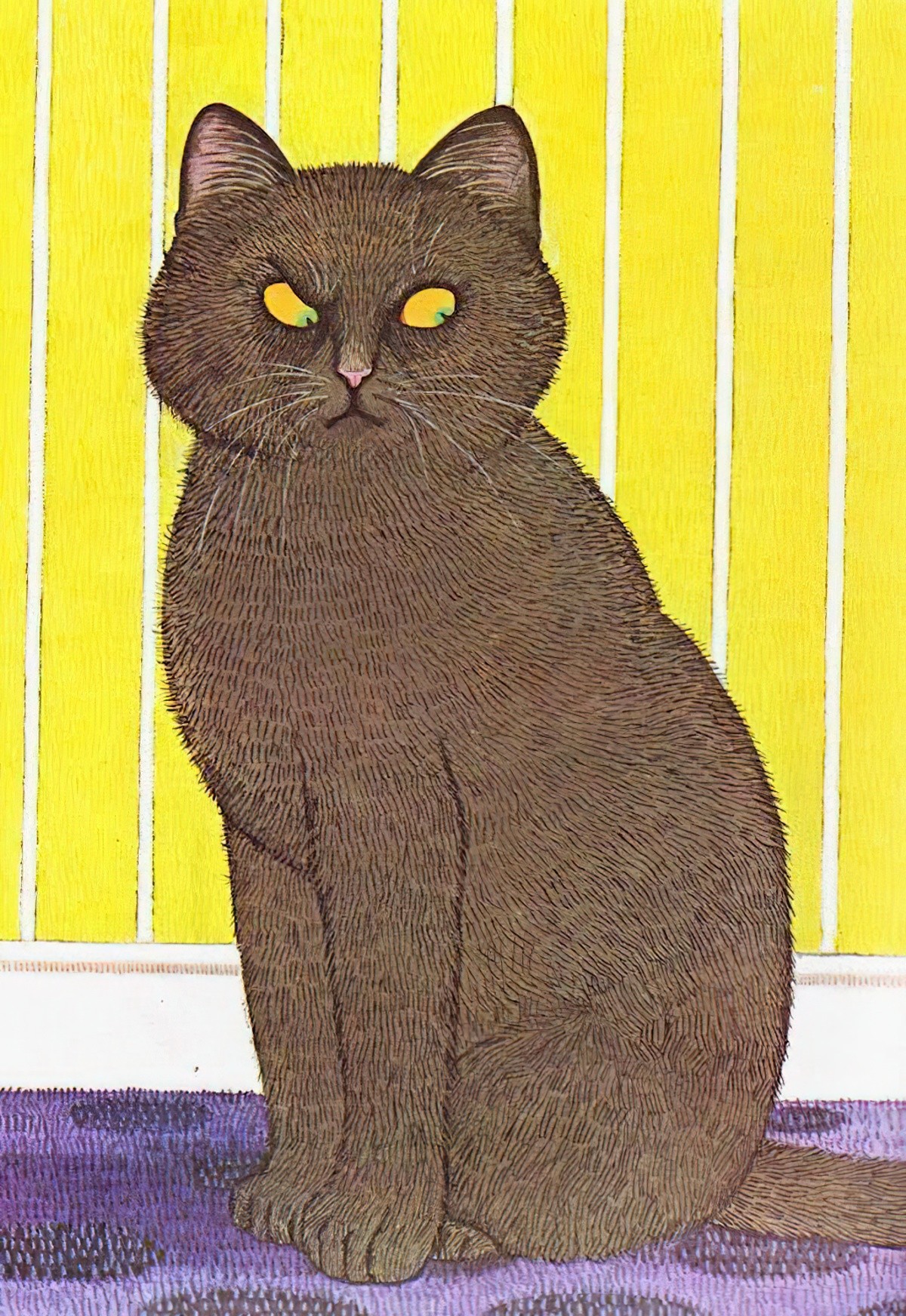

The writer really makes the most of this wallpaper personification: The wallpaper is basically alive (or rather, half alive, half dead, with its broken, lolling neck). Hard angles, too, are often used in visual imagery when it comes to the horror genre. (See The Dark, by Lemony Snicket and Jon Klassen for a picturebook example.)

It is a big, airy room, the whole floor nearly, with windows that look all ways, and air and sunshine galore. It was nursery first and then playroom and gymnasium, I should judge; for the windows are barred for little children, and there are rings and things in the walls.

The paint and paper look as if a boys’ school had used it. It is stripped off – the paper in great patches all around the head of my bed, about as far as I can reach, and in a great place on the other side of the room low down. I never saw a worse paper in my life.

One a those sprawling flamboyant patterns committing every artistic sin.

It is dull enough to confuse the eye in following, pronounced enough to constantly irritate and provoke study, and when you follow the lame uncertain curves for a little distance they suddenly commit suicide – plunge off at outrageous angles, destroy themselves in unheard of contradictions.

[…]

There is a recurrent spot where the pattern lolls like a broken neck and two bulbous eyes stare at you upside down.

I get positively angry with the impertinence of it and the everlastingness. Up and down and sideways they crawl, and those absurd, unblinking eyes are everywhere There is one place where two breaths didn’t match, and the eyes go all up and down the line, one a little higher than the other.

I never saw so much expression in an inanimate thing before, and we all know how much expression they have! I used to lie awake as a child and get more entertainment and terror out of blank walls and plain furniture than most children could find in a toy-store.

When Else describes a view from this big, airy room we get more of a traditionally gothic impression:

Out of one window I can see the garden, those mysterious deepshaded arbors, the riotous old-fashioned flowers, and bushes and gnarly trees.

This stands in juxtaposition with her view out the other side:

Out of another I get a lovely view of the bay and a little private wharf belonging to the estate. There is a beautiful shaded lane that runs down there from the house.

And at this point we are encouraged to wonder which part of this story is psychosis and which part is a haunting:

I always fancy I see people walking in these numerous paths and arbors, but John has cautioned me not to give way to fancy in the least. He says that with my imaginative power and habit of story-making, a nervous shortcoming like mine is sure to lead to all manner of excited fancies, and that I ought to use my will and good sense to check the tendency. So I try.

TECHNIQUES OF NOTE

Haunted House Trope

The trope of the suspiciously cheap lodgings which end up being haunted is fairly common in the horror genre. The Scariest Night, an Apple classic from the early 1990s by Betty Ren Wright is an example from children’s book world. TV Tropes call this trope Haunted Headquarters, which covers any kind of haunted primary setting, not just big fancy houses.

There are other horror symbols utilised in this story, such as the moon:

The moon shines in all around just as the sun does. I hate to see it sometimes, it creeps so slowly, and always comes in by one window or another.

The dark is important, as all of the worst things happen during the night. The moon is as bright as the sun in this case, though, because of all the forced rests during the day, which inevitably lead to a disrupted sleep pattern and night-time insomnia.

Epistolary Structure

The reader is constantly reminded that this is a retelling of a story, and the narrator isn’t meant to be all that good at writing, despite being ‘a writer’ in the story. We’re supposed to believe she’s down-to-earth and therefore incapable of fabricating events. After going off topic to write a little about some legal trouble she says:

That spoils my ghostliness, I am afraid, but don’t care – there is something strange about the house – I can feel it.

Another short story writer, Katherine Mansfield, used many hyphens in her personal writings. I suspect hyphens to join grammatically disconnected clauses were in fashion for a while.

Making Use Of The Senses

Describing how things look is something writers find easy; we have to dig a little deeper when engaging the sense of smell:

It gets into my hair.

Even when I go to ride, if I turn my head suddenly and surprise it – there is that smell!

Such a peculiar odor, too! I have spent hours in trying to analyze it, to find what it smelled like.

It is not bad – at first, and very gentle, but quite the subtlest, most enduring odor I ever met.

In this damp weather it is awful, I wake up in the night and find it hanging over me.

It used to disturb me at first. I thought seriously of burning the house – to reach the smell.

But now I am used to it. The only thing I can think of that it is like is the color of the paper! A yellow smell.

POLITICS

We don’t often get such a direct insight into why a short story has been written, but we do in this case. See Why I Wrote The Yellow Wallpaper.

- This is obviously a feminist short story — an ‘hysterical woman’ who has what we today recognise as post-partum depression, not taken seriously by the learned men in her life: ‘He knows there is no reason to suffer, and that satisfies him.’ It’s possible Else is not bonding particularly well with the baby, which is not mentioned until second five. The baby is cared for by someone called Mary.

- A desire to work but being told she is too feeble of mind

- Writing in secret, which itself causes stress because of having to keep it hidden: ‘There comes John, and I must put this away – he hates to have me write a word.’

- A husband who won’t let his wife make any decisions — he even controls which bedroom they sleep in. This is a classic case of a controlling partner dominating their spouse by exerting control in the name of love: ‘He is very careful and loving, and hardly lets me stir without special direction. I have a schedule prescription for each hour in the day; he takes all care from me, and so I feel basely ungrateful not to value it more.’ He infantalises her by callling her his ‘dear little goose’.

- While most monsters and ghouls in horror stories are gendered male, if gendered at all, the monsters in the wallpaper comprise a group of women. She reasons these women are trying to climb through the patterns in the wallpaper but end up strangled. This, of course, is a comment on how many mentally ill women are cloistered as the crazy ‘woman upstairs’, also known as the Madwoman in the Attic. (The ur-Madwoman is Mr Rochester’s wife from Jane Eyre, by Charlotte Bronte.)

RESONANCE

The promotion and reaction to [Volvo’s] Your Concept Car [‘by and for women’], grants women a room of their own, but this room may well have a locked door and yellow wallpaper. By celebrating women’s access to a room (design of a concept car), the male-dominated automotive industry can claim accommodation of women while still consigning them to subservience or invisibility in the overall economic landscape (the automotive industry).

“A Car of Her Own: Volvo’s “Your Concept Car” as a Vehicle for Feminism? by Roy Schwartzman and Merci Decker, 2008

COMPARE AND CONTRAST

The guys at the Overdue podcast compares this story with Shirley Jackson’s “The Lottery” because both stories are by women and are subversive.

Neo-gothic stories which centre the Othered woman are popular now, and a standout example is The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood. “The Yellow Wallpaper” is a much earlier example of a story concerned with how the patriarchy feels the burden of subduing female procreation lies with men. (Pregnancy and unharnessed sexuality has long been conflated.)

One

When she had referred to herself as Nightbitch, she meant it as a good-natured self-deprecating joke–because that’s the sort of lady she was, a good sport, able to poke fun at herself, definitely not uptight, not wound really tight, not so freakishly tight that she couldn’t see the humor in a lighthearted not-meant-as-an-insult situation–but in the days following this new naming, she found the patch of coarse black hair sprouting from the base of her neck, and was, like, What the fvck.I think I’m turning into a dog, she said to her husband when he arrived home after a week away for work. He laughed and she didn’t.

She had hoped he wouldn’t laugh. She had hoped, that week as she lay in bed, wondering if she was turning into a dog, that when she said those words to her husband, he would tip his head to one side and ask for clarification. She had hoped he would take her concerns seriously. But as soon as she said the words, she saw this was impossible.Seriously, she insisted. I have this weird hair on my neck.

She lifted her normal hair to show him the black patch. He rubbed it with his fingers and said, Yeah, you’re definitely a dog.

To her credit, she did appear more hirsute than usual. Her unruly hair moved about her head and shoulders like a cloud of wasps. Her brows caterpillared across her forehead with unplucked growth. She had even witnessed two black hairs curling from her chin and, in the right light–in any light at all, to be honest–you could see the five o’clock shadow of her mustache as it grew back in after her laser treatments. Had she always had so much hair on her arms? Descending the edge of her jaw from her hairline? And was it normal to have patches of hair on the tops of your feet?

And look at my teeth, she said, baring her teeth and pointing to her canines. She was convinced they had grown, and the tips had narrowed to ferocious points that could cut a finger with a mere prick. Why, she had nearly cut hers during her nightly examination in the bathroom. Every night, when her husband was gone and their son was happily playing with trains in his pajamas, she stood at the mirror and pulled her lips back from her teeth, turned her head from side to side, then tilted her head back and looked at her teeth from that bottom-up angle, searched the Internet on her phone for pictures of canines to which she might compare her own, tapped her teeth with her fingernails, told herself she was being silly, then searched humans with dog teeth on her phone, searched do humans and dogs share a common ancestor, searched human animal hybrid and recessive animal genes in humans and research human animal genes legacy, searched werewolves, searched real werewolves in history, searched (somewhat inexplicably) witches, searched (somewhat relatedly) hysteria 19th century, and then, since she wanted to, searched rest cures and The Yellow Wallpaper, and she reread The Yellow Wallpaper, which she had once read in college, then stared blankly for a while at nothing in particular while sitting on the toilet, then stopped searching altogether.

opening to Nightbitch, a 2022 novel by Rachel Yoder

RESOURCES

THE YELLOW WALLPAPER: CRASH COURSE LITERATURE #407

Introduction from Dr. S. Weir Mitchell and his Rest Cure

In this episode, we discuss “The Yellow Wall-Paper” by Charlotte Perkins Gilman. What can we learn from a 19th-Century Feminist short story? How does the diary-entry structure inform the way we read? How is a first-person point of view affected by the diary format? How does the horror genre help serve the story’s social commentary?

Why Is This Good? podcast

The header photo was taken when Charlotte Perkins Gilman was about 40 years old.