The Wizard of Oz is in some ways the inverse of Winnie the Pooh. Whereas L. Frank Baum’s Oz series is so highly metaphorical every member of a thinking audience weaves their own symbolism into it, Milne’s Pooh series is so devoid of symbolism that it’s famous among specialists of children’s literature for precisely the fact that you can’t do a serious close read on it. (See: The Pooh Perplex, a satire of literary criticism.)

MARGARET ATWOOD: Let’s talk about The Wizard of Oz.

TYLER COWEN: Sure.

ATWOOD: Now, there’s an absolutely core to the American psyche —

COWEN: It’s an economics movie. It’s about bimetallism, right? The yellow brick road is about the gold standard? This is not commonly known, but it’s true.

[laughter]

COWEN: It’s a monetary allegory, the whole movie.

ATWOOD: You think so?

COWEN: I know so.

ATWOOD: You know a lot of things. So, the Tin Woodman is what in it?

COWEN: He’s one of the people in the bimetallist debates. But there was a Journal of Political Economy article going through all of the parallels.

ATWOOD: And Dorothy is what?

COWEN: I think just the innocent American crying for relief.

ATWOOD: Are you buying any of this? I’m not.

[laughter]

ATWOOD: And the tornado is?

COWEN: Maybe depression, deflation.

ATWOOD: And Toto is?

COWEN: That one I’m stumped on.

[laughter]

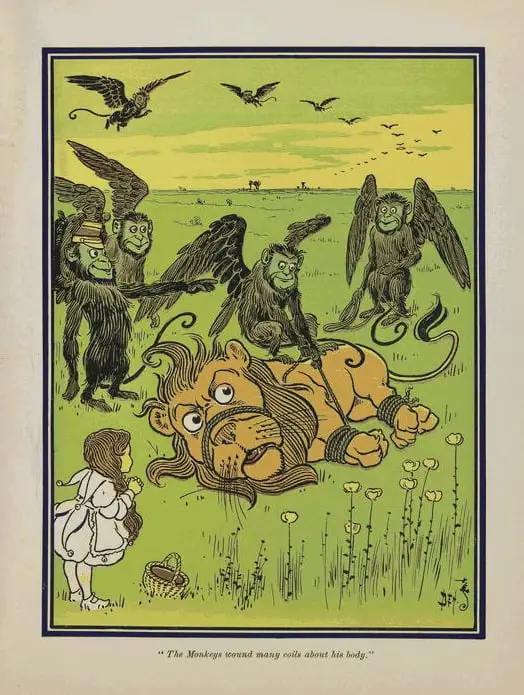

ATWOOD: The flying monkeys are?

COWEN: William Jennings Bryan?

ATWOOD: Okay. Well, here’s the really interesting thing about Wizard of Oz. In The Wizard of Oz, the male wizard is a fraud, and all of the other male characters are missing something.

COWEN: That’s right.

ATWOOD: Yes. But the witches are real.

Margaret Atwood in conversation with American economist Tyler Cowen (2019)

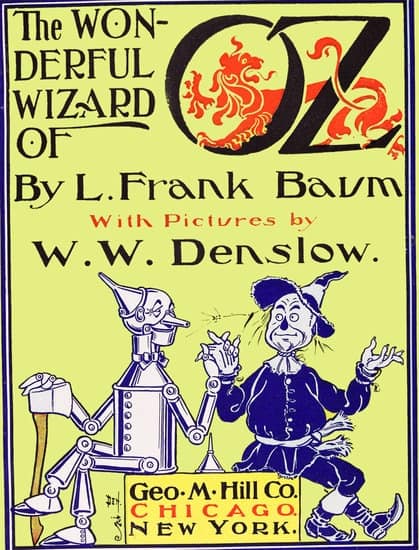

Listen to The Wonderful Wizard of Oz at Librivox

GIFT IDEA FOR LOVERS OF THE WIZARD OF OZ

STORY STRUCTURE OF THE WIZARD OF OZ

The overall structure of The Wizard of Oz is a very old, very successful one. We might call it a Home-away-home story. We might call it linear, we might call it a quest or adventure story. Or we might call it a modern Gilgamesh myth, after one of the earliest and most famous examples of this narrative journey.

GILGAMESH AND THE WIZARD OF OZ

The nature of the quest story is explained succinctly by Michael Foley in his pop-psychology book The Age of Absurdity, and I’ll quote him here because he links that old Epic to the modern Wizard of Oz:

There is a rich and unbroken tradition of quest literature running from The Epic of Gilgamesh in 1000 BCE to The Wizard of Oz in the twentieth century. The scholar of myth, Joseph Campbell, has shown how the quest saga has been important in every period and culture and always has the same basic structure, though local details may vary. Each saga begins with a hero receiving a call to adventure which makes him abandon his familiar, safe environment to venture into the dangerous unknown. There, he undergoes a series of tests and trials, negotiates many difficulties and slays many monsters. As a reward he wins a magical prize — a Golden Fleece, a princess, holy water, a sacred flame or an elixir of eternal life. Finally he brings the prize back from the kingdom of dread to redeem his community.

This narrative hasn’t always been the dominant one; the Quest Story started with The Epic of Gilgamesh. Before that, stories tended to star female characters, because they were about the birth of the world, and in order for things to come into existence, our ancestors believed that a female being was necessary. If you’ve never read The Epic of Gilgamesh, here’s Foley’s summary:

The hero, Gilgamesh, a Mesopotamian king, becomes disenchanted with his kingdom and life and departs on a quest, which involves dealing with ferocious lions, scorpion men and a beautiful goddess who attempts to detain him with surprisingly modern temptations: ‘Day and night be frolicsome and gay; let thy clothes be handsome, thy head shampooed, thy body bathed.’ Nevertheless, the hero persists in his quest and, diving to the bottom of a deep sea, plucks the plant of immortality. But the ending has a nasty twist that would have to be changed in any movie version: when Gilgamesh lies down to rest a serpent steals the plant, eats it and attains eternal youth. In mythology the snake is always the villain.

Some writers argue a case for a departure from these old stories, as have others before him. (See Marjery Hourihan: The Centrality of The Adventure Story) But can we ever really get away from this narrative? Foley says we’re all living the narrative. By ‘abstract seeker’ he’s talking about people who say they ‘want to travel’, but if you were to ask them to where, and for what purpose? they would be hard-pressed to say why — instead, the modern imperative is to be constantly on the move.

Campbell argues that these narratives symbolize an essentially inward journey—the hero breaks free from the conventional thinking of his time, ventures out into the dark of speculative thought, finds the creative power to change himself and wishes to share this with others. The prize won after much uncertainty and danger is knowledge. “The hero is the one who comes to know.” So the narrative has four stages: departure, trial, prize, return; these are the same as the goals of the abstract seeker: detachment, difficulty, understanding, transformation.

PARATEXT

SHORTCOMING

Dorothy is a hapless hero: caught up in a whirlwind, she is credited with killing the Wicked Witch of the East. But she’s not a killer. She’s a victim of circumstance. First she puts on the silver shoes that belong to the dead witch. (Can you imagine killing someone then taking off their shoes and putting them on? Gruesome. However, we’re not meant to dwell on that. These shoes are fairytale symbolic.)

Although Dorothy herself is the upbeat Every Child, the characters she meets along the way each has an obvious and significant weakness:

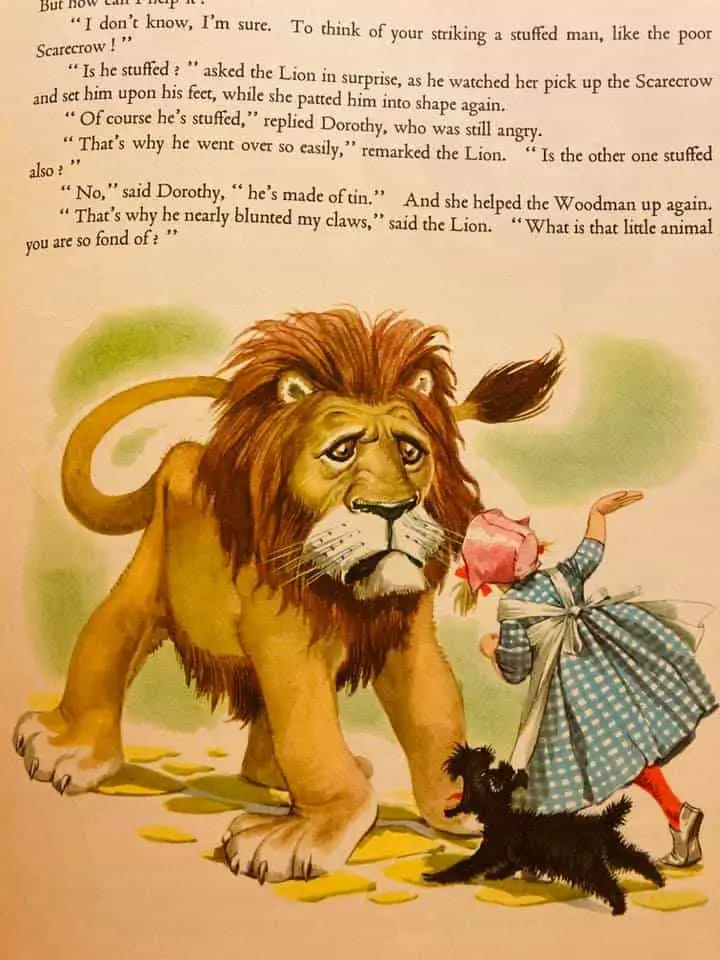

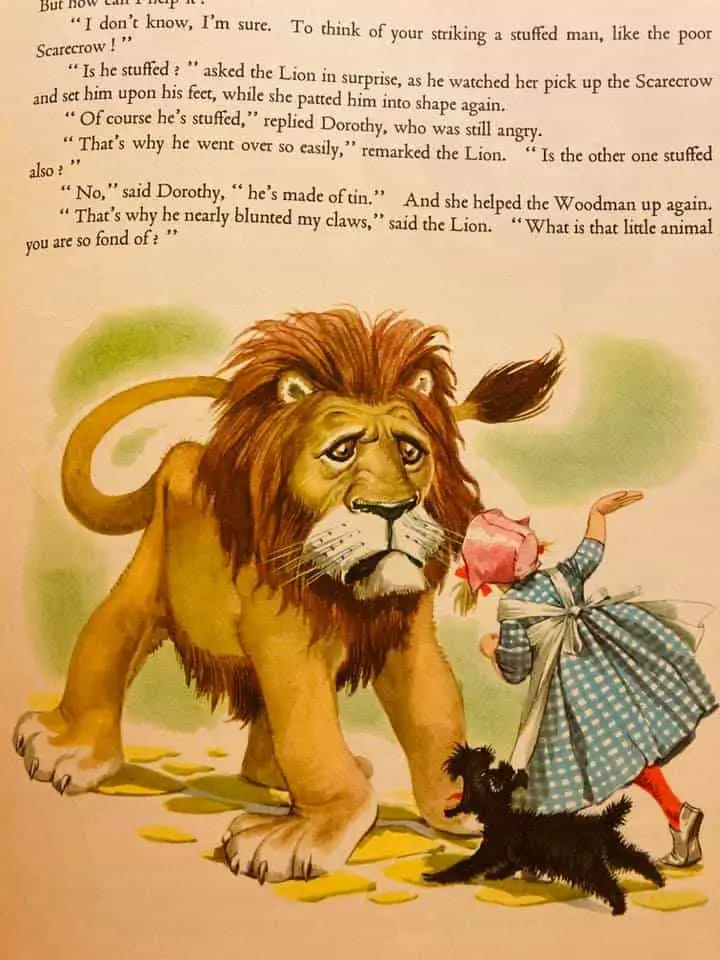

The Scarecrow doesn’t have a brain; the Woodman doesn’t have a heart; the Lion doesn’t feel brave even though he is expected to show it (a portrait of masculinity?). Together, these different bodies represent a composite of the naive, emotionally undeveloped, timid Every Child. Dorothy is the viewpoint character.

DESIRE

Dorothy’s mission is to get back home to Kansas. Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away functions in a very similar way; a girl enters a fantasy realm by accident and her mission is to get back home. She must first spend time in this world and decipher its magic, and not be evil.

OPPONENT

Now, as in any mythic journey, Dorothy will meet various characters along her journey (literally a road in this case). She must decide for herself whether each of these characters is an ally or an opponent. She doesn’t know if the Wizard of Oz is going to be an ally or an opponent, and this is the main part of the mystery of this story, propelling the reader forward.

From the opening we know that the Wicked Witch of the West is still alive. This is Dorothy’s Minotaur opponent. She eventually hears that Dorothy and her mates are out to kill her. So she sends out fierce wolves to hunt them down.

The Wicked Witch of the West did not seem to ‘belong’ to the bright and pretty world of Oz; she overwhelmed its illusory harmony; her presence was too strong to be contained within its fictional and discursive borders. She did not make sense taken together with the dainty china milkmaids and cute Munchkins; in some way, she therefore came to stand for the irruption of chilly but exhilarating reality into the artificial security of a comfortably privileged childhood.

Diane Purkiss, The Witch in History: Early modern and twentieth-century representations

PLAN

Dorothy reaches the Wizard of Oz hoping he’ll show her how to get home to Kansas but instead he gives her a mission: Since she so successfully murdered one of the bad witches, now she must murder the other. Dorothy isn’t mad keen on that idea. Each of her friends goes in to see the Wizard and each time he looks different. He won’t grant any of them their desires until the other wicked witch is dead.

THE BIG STRUGGLE

The plan goes wrong when the wicked witch captures Dorothy. Baum uses magic in a convenient way; Dorothy can’t be harmed because of the apotropaic magic kiss she was given by the Good Witch.

In a Cinderella-esque turn of events, the wicked witch orders Dorothy to scrub floors for her. The kind-hearted Dorothy gets so mad that she throws a bucket of water all over the witch. In a trope later used by Manoj Nelliyattu “M. Night” Shyamalan, it just so happens that water can kill the enemy. (Dorothy really is quite the accidental murderer.)

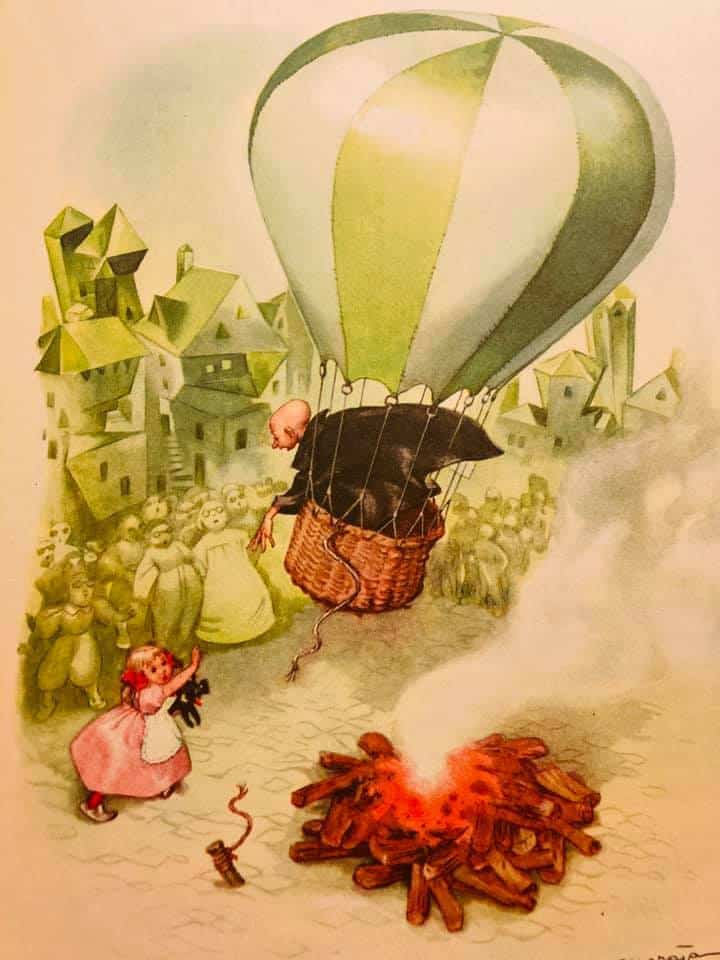

Now the story turns a bit Pied Piper (Dorothy is the Piper). Dorothy and her friends return to the Wizard of Oz because they’ve done as he’s asked, but now he’s not going to fulfil his end of the bargain.

Now the Lion finds his voice, as Dorothy already has. The lion roars and frightens the Wizard, who reveals himself to be a frightened, little old man. And since he is frightened, we code him as ‘kind’.

ANAGNORISIS

He puts straw into the scarecrow’s head, a silk heart inside the Tin Woodman, and gives the lion some green medicine for courage. Without using the word ‘placebo effect’, this part of the story is about the placebo effect. These characters didn’t need a man from on high fixing their greatest weaknesses; they only needed to believe in themselves (after being pushed to the limits, of course).

The message here: Even with your great shortcomings, you are far more powerful than you think!

Unfortunately, Dorothy is still stuck in the Land of Oz. So they make a new plan. They will go to the other good witch, the witch of the South, and ask her for help. This Good Witch guilt trips her. What will happen to your new friends when you are gone?

It turns out that Dorothy could’ve gone home right at the beginning of the story because her silver magic shoes can take her anywhere she wants to go. But she didn’t know that.

NEW SITUATION

Dorothy’s new friends don’t need her continued emotional labour because they believe in themselves now, so they get to be rulers in a hierarchical society where confidence is king. The scarecrow will be the ruler of Emerald City, the Tin Woodman will rule over the Winkies, and the Lion will be King of the Forest.

EXTRAPOLATED ENDING

This is clearly a patriarchal order. The ideology may be covert, but we shouldn’t accept it as the natural order of things; that communities need rulers coming in from the outside, telling them all what to do and how to live. Also known as colonialism.

RESONANCE

The 20th century film adaptation of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz ensured the story’s longevity. We now call it simply The Wizard of Oz. Modern child audiences may have been exposed to the film Oz and be most familiar with the story that way. Simplified versions have been published in the Little Golden Books series and the Ladybird Favourite Tales series.

There are many sequels to The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, but, as in Anne of Green Gables, it’s the first in the series which has found longevity, with the rest of the story largely falling into obscurity.